Tayari Jones: So first off, how is the weather down there?

Ravi Howard: I almost hate to say it to people who are not down here, but we got into the 60s today.

TJ: Don’t rub it in. I’m wearing my puffy coat indoors at this point.

RH: I’m not rubbing it in. I feel your pain. You remember that I lived in New Jersey for seven years.

TJ: Did you write much when you were up here?

RH: When I was up there I was writing about Alabama, but I was writing about the South from a remembered space. Even though I had been gone for years, stories about home were primarily what I was writing and imagining.

TJ: Same here. Even though I have mastered the New York subways (at last), when I sit down to write, my imagination unfolds in Atlanta. This is why I will always think of myself as a Southern writer, no matter where I happen to hang my hat.

RH: Didn’t I just see that you were invited to join the Fellowship of Southern Writers?

TJ: Yes! I am so excited. Often, I am not considered a Southern writer, because I am black and writing about Atlanta and urban spaces. So I wanted to be let into the Southern writer party.

RH: Yes, it’s important that black writers claim and be claimed by the South.

TJ: So I’ll take that to mean that you think of yourself as a quote-unquote capital S Southern writer?

RH: Yes, but I prefer the idea of layers of labeling. We can define ourselves with those layers. Black writer. Southern writer. Some folks are Urban Southern. Historical Southern. Gulf Coastal writers. Layers give you specificity. And you can use as many layers as you need to get to the heart of the matter.

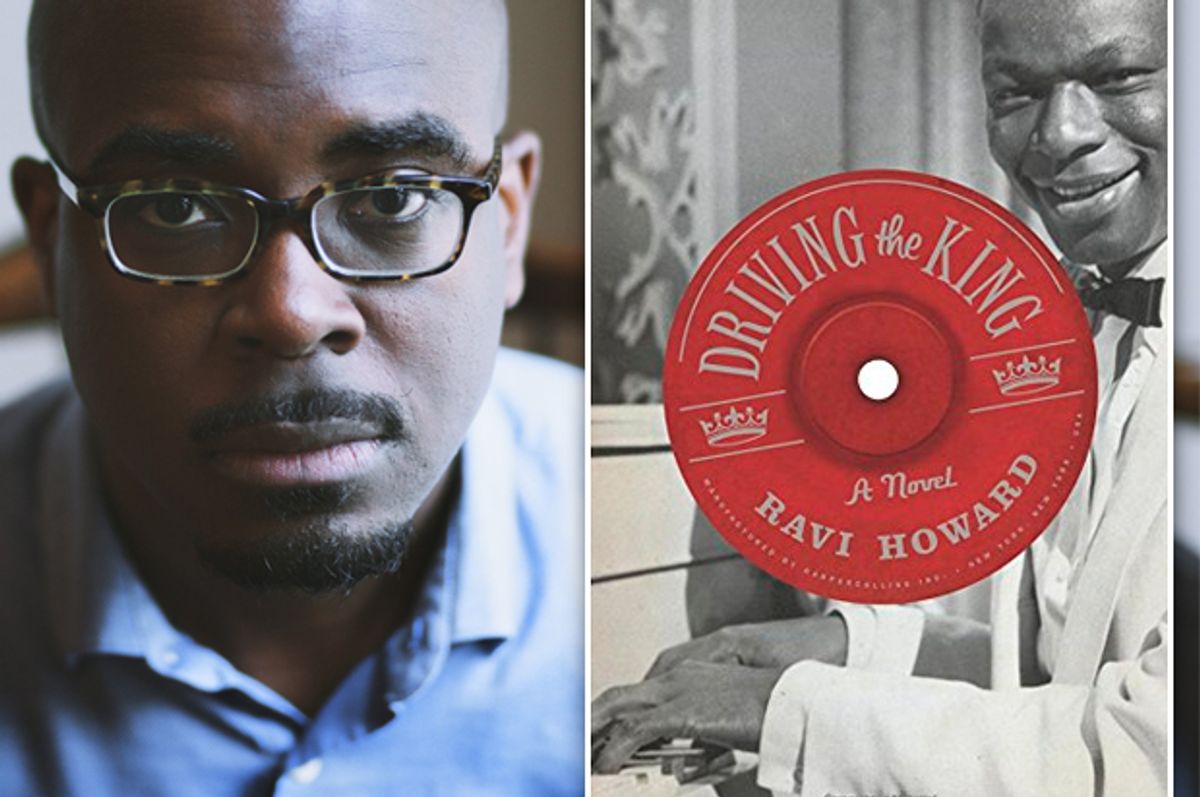

"Driving the King" is my second novel set in Alabama, and that specificity is important because it lets me return to that space because I can fine-tune the characters and space without the feeling of being pigeonholed.

TJ: What if you are a pigeon and that’s your hole? I kind of feel like that sometimes.

RH: (laughs)

TJ: Alabama is the second most Southern state, in my view, just after Mississippi. Did you see "Selma"? I loved how it was completely Alabama and completely Southern, and completely dignified. A lot of spray starch was expended in the making of that film!

RH: I’m excited to see it, and I’m going this weekend. I saw a "Selma" presentation by Ava DuVernay at the Bronze Lens Film Festival. I loved her first two films.

TJ: One thing I thought about "Selma," and it made me think of "Driving the King," is the way that a certain African-American middle-class affect performance was still a part of the movement.

RH: As a writing exercise for my students, I give them pictures of James Hood and Vivian Malone on the day they integrated the University of Alabama. They’re surrounded by press and police. You can look at his hat, and you can look at her dress and tell that they had gone through certain motions preparing, almost this sense of character development for that moment. It speaks to what we do as writers, showing what happens before people get on that fiction stage. In "Driving the King," we have Nat King Cole, a black star, his chauffeur and his car -- they are an extension of that. As he’s moving from one stage to the next, there is a sense that he must always be prepared for the next moment. I wanted to show the parallels between black Hollywood and the civil rights movement. There was a sense of casting there. Jackie Robinson. Martin Luther King Jr. Rosa Parks. None of them were the first to try and do what they did, but they were perfectly cast at the right time. Same with Nat King Cole. He wasn’t the first singer, but he was the right man at the right time.

TJ: How did Nat King Cole become Nat King Cole? I think that’s the question of your novel, right? There are two boys, both named Nathaniel, both black in Montgomery. Where one become known as “King” and the other by his last name, “Weary.”

RH: Nat King Cole was a great piano player in a trio, and then it became obvious that he was a great singer. He needed to be in the same space as Sinatra and the other great singers at the front of the stage. I think he embraced that, hoping it could break open doors for others who wanted television shows.

Also, he and Jackie Robinson were good friends and would watch each other. So I think that friendship was a result of that role. Prime-time television was Major League Baseball. He referred to himself as the Jackie Robinson of television at one point. Black entertainers recognized the history they needed to make.

TJ: Speaking of “making” history. This is a historical novel, but you took a lot of liberties with the record, didn’t you?

RH: Well, the incident that sparks the novel is true. Nat King Cole was attacked onstage by a racist mob, but this was actually in Birmingham, not Montgomery. Also, he was attacked in 1956, and I moved that moment to 1945. I thought the moment of his attack fit what happened when black veterans were attacked after World War II. I wanted to give myself a lot of space for the story since it was being told from the perspective of a fictitious driver.

I look artistic license like someone playing a radically different version of a jazz standard. It doesn’t hurt the standard at all, and it may bring the standard into a conversation for those who don’t know it.

TJ: Me personally, I’m fine with playing fast and loose a little bit. You’re a novelist, not a documentarian.

RH: And I can’t really see a documentary being terribly interested in the life of Cole’s chauffeur, but in my novel, he’s the narrator. In real life the chauffeur sees everything. He’s the perfect narrator, but working-class people’s stories are too often forgotten. Think about how many folks were not a part of the record. There were 50,000 black people in Montgomery during the boycott, so you think about all of those stories that are pretty much anonymous. They’re part of the collective, and in fiction we’re peeling characters away from that collective and giving them a voice. They had small roles, but those characters drive fiction. We can bring those anonymous folks out in a way that nonfiction can’t.

TJ: One more question. What is your favorite Nat King Cole song?

RH: "Let's Face the Music and Dance. " The first line of the song is, “There may be trouble ahead.”

Atlanta native Tayari Jones is the author of three novels, most recently "Silver Sparrow." She is on the MFA faculty of Rutgers-Newark University, and on Twitter @tayari.

Shares