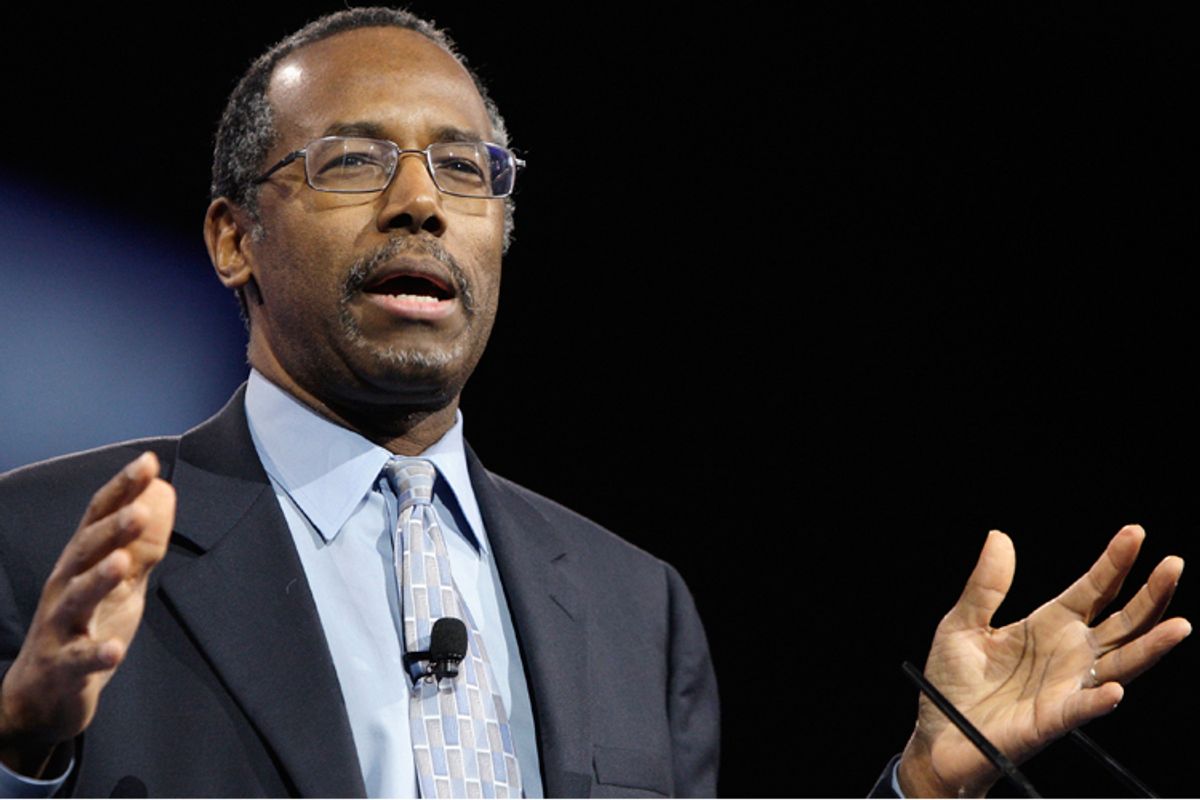

It seems downright bizarre from today's perspective, but there was a time, really not so long ago, when the conventional wisdom held that the first African-American president would probably be a Republican. Of course, today's Republican Party is the preferred home of neo-Confederates, states' rights absolutists, David Duke wannabes and all manner of race-politics reactionaries. But as we saw with Herman Cain in 2012, and will perhaps see again with Ben Carson in 2016, Republican voters are at least willing to consider supporting an African-American for president (provided he's a doctrinaire conservative, that is).

And if we shift our focus away from recent years and look instead to the full breadth of American history, the relationship between African-Americans and the GOP gets even more complicated. For one thing, the Republican Party, at least technically, is still the Party of Lincoln; and, indeed, there are millions of Americans alive today who can recall an era from within their own lifetimes when the Democratic Party's hold on the African-American vote wasn't nearly as viselike as it is today. As the historian Heather Cox Richardson has argued, the GOP's lack of support from African-Americans wasn't preordained or due to happenstance. Party leaders made deliberate choices — and they can do it again.

Because we were interested in learning more about the tortured history between the Grand Old Party and African-Americans, Salon recently spoke over the phone with Harvard professor Leah Wright Rigueur, author of "The Loneliness of the Black Republican: Pragmatic Politics and the Pursuit of Power." Rigueur told us about how the GOP used to be viewed by African-Americans, why they broke apart, and what makes contemporary African-American Republicans like Ben Carson or Condoleezza Rice similar (and different) from their their predecessors. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

So to start off, I wanted to ask what made you want to take such a close look at this slice of U.S. political history?

I've always been interested in politics and history and things like that and I decided that black Republicans was a topic that no one had really looked at within the study of American politics. As I mention in the introduction to the book, there have been studies here and there — very piecemeal — but nobody had really looked at this period from 1936 to 1980 or even present day to explain the phenomenon of black Republicans. When I first started on the topic a lot of people made joked about, Oh, are you going to look at black Republicans? All three of them? Ha-ha. But as I started digging, even just scratching the surface, I found that there were hundreds, even thousands, of documents and stories about African-Americans in the Republican Party, so I decided that this was really an overlooked part of American politics.

I also should say that I'm not a Republican, so I didn't have an agenda going in here. But what came out of it was that there are a couple of critical lessons to be learned. That's why I proposed putting together a comprehensive history of a segment of the Republican Party, and really of politics in general that had just been either neglected, left out, at times ridiculed, or really just misunderstood by conservatives and liberals alike.

Was there ever a time when people wouldn't consider the concept of a black Republican to almost be an oxymoron or a joke? How far back to you have to go before that's true? Nixon got around a third of the African-American vote in the 1960 election, right?

Right, about 32 percent. Really, there are a couple of different points, but I put the big break in 1964, which is when the Republican Party gives Barry Goldwater the presidential nomination and he runs against Lyndon Johnson. He gets the nomination a few weeks after he has voted against the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which we all know Lyndon Johnson had shepherded through Congress.

That is just a huge breaking point for African-American voters. On the one hand, you have this presidential candidate who has really proven himself to be an advocate for civil rights, regardless of what's going on in his personal life. He has pushed this bill through Congress and it's an incredibly comprehensive and progressive bill for civil rights. Then you have the Republican Party's candidate, who's essentially saying, I can't vote for this bill on principle. Well, principle is all good and dandy, but, you know, at the end of the day that doesn't protect your civil rights. So you do see an incredibly hard, harsh break in 1964 but even before that, black support for the Republican Party has been eroding.

One of the arguments I make is that what is remarkable about the pre-1964 period is that the kind of work that black Republicans do actually means that fewer people leave the party than would have. Really, through 1960, 1961, '62, '63, it's still common for [black] people to identify as a Republican. They may not necessarily be voting like that, they may not be publicly proclaiming that, but it's not uncommon to hear African-Americans say, I'm a registered Republican or I'm going to vote for this Republican candidate or I love Nelson Rockefeller.

Can you explain the ideology of the pre-Goldwater GOP, insofar as African-Americans are concerned? What was it about the GOP before him that was attractive to many of them?

Through 1936, African-Americans really have what we might call a strong historical memory and attachment to the Republican Party. It's still, in their minds, the Party of Lincoln, even though there are certain presidential figures, like Herbert Hoover, who push a lily-white party, and even though, through 1936, you start to see some strains of the Republican Party wanting to distance itself from the idea of civil rights. Still, in the minds of many African-Americans through 1936, the Republican Party is the party of civil rights and the Democratic Party is the party of repression — especially in the South.

As African-Americans begin to migrate to the North as part of the Great Migration, we start to see a transformation in how alliances and political parties work. Northern Democrats start building relationships with the blacks who are moving north, and you can really see this in cities like Chicago, for example. Even though millions of Africans-Americans vote for Roosevelt in 1936, it's still not the attraction we think about today. We also still see a lot of switching going on in 1944 with Truman, and really in 1948 with Truman, but a lot of this has to do with the desegregation of the Armed Forces and Truman pushing aggressively for civil rights, as well as Southern Democrats breaking off within the Democratic Party and forming the States' Rights Party that was all about segregation forever.

What's going on, I think, in the Republican Party is that there's really a battle over what the Republican Party should represent in terms of civil rights. The Republican Party does this dance with black voters where they say, "We want to go after black voters but we're not sure we want to invest the time and the money into going after them." So they again, do things that are piecemeal— putting in a lot of money and then taking a lot of money out; getting figures like Joe Louis or Jesse Owens to campaign but then not really doing much during the off season is hiring Ralph Bunche to do a comprehensive overview of how to get back the black vote in 1944. Bunche writes this really comprehensive report, gives it to them, the Republican Party loves it, and then what happens? They don't really enact any of his suggestions; they table it.

We see this going back and forth, and then in the 1950s, even as they're investing money into minority outreach it's so piecemeal and at the same time they're pouring money into figuring out how to get white Southern voters. I think the interesting thing is that strategists working within the Republican Party are arguing, if we want to go after white Southerners we can't go after black voters. They see them as mutually exclusive. You have these black Republicans in the party who are going, No, no, no, we can go after black voters! What we can't go after are white Southern racists! So it's kind of a balancing act through the 1950s.

What ends up happening is that when black voters see that there are no differences in civil rights between Democrats and Republicans they tend to vote in their economic interests, which I thought was fascinating. When they do see hard differences in civil rights, they vote for whatever Party they think has their civil rights interests in mind, so there's a lot of weighing of what goes on with economics and with racial inequality.

That's very interesting, especially considering that most Republicans claim to promote economic policy that's inherently in the interests of black voters. The appeal of that— stipulating whether it's even true— disappears among African-American voters if they lack a sense of being considered as full persons.

Exactly. This is one of the things I really pushed in the book: If you don't have the luxury of being seen as a first-class citizen then you can't necessarily vote for a party, even if that party has your economic interests or your foreign policy interests in mind. As Barry Goldwater is pushing this line of the individual being what's important and individual rights, black Republicans are saying, That's great; I would love to get to the point where I can be seen and treated as an individual. However, since we're not at that point, my group needs recognition of my civil rights, of my human rights. And then we can get to the individual part.

Can you tell me about whichever figures you think are the most representative of the trajectory you outline? When you think of these prominent, influential African-American Republicans, who are the people that come to mind?

The first one that comes to mind is the one who just passed away, [former Senator] Ed Brooks. I think that as the dozens, maybe even hundreds of obituaries that have come out in the past couple days have shown, he had a huge impact, not only on Republican politics but on American politics in general. The other figure I really like to talk about is Jackie Robinson because everybody knows him for his athletic accomplishments but very few people know how actively involved in politics he was— and when I say, actively involved, he described himself as a militant black Republican, which doesn't necessarily have the connotation we would think of. He was militantly for the rights of black people within a Republican framework. Those really are the two that first jump out to me.

Then there are a whole host of other people I talk about within the book, which includes William Coleman, who's still alive and still practicing in D.C. but who was secretary of transportation under the Ford administration and who really used his position to push for civil rights agendas. He has this fabulous partnership with the mayor of Atlanta in the 1970s and helped get what we now know as the Delta Terminal in the Atlanta Airport built. There are so many other figures like Art Fletcher, who we might call the godfather of affirmative action. He plays a tremendous role during the Nixon administration along with other figures like Bob Brown.

One other figure I like to mention is Gloria Toote, and I think that's because she's such a confounding figure. She's incredibly liberal— at least when we first meet her in the 1970s— and working in the Ford administration and aggressively pushing for funding for civil rights projects and equal opportunity projects, but during the 1976 convention she actually comes out and seconds the nomination of Ronald Reagan. Even though he seems opposed to everything she believes in, she becomes one of his very close advisors after that whole incident, and she says this is because even though they disagree he listens to her. He listens to her demands and her concerns.

For people who might now know, can you tell me a little bit about what Jackie Robinson wrote about his experience at the '64 convention?

Jackie Robinson was interesting. If you look at pictures from the area he's all over the convention and he essentially says it is a disaster. He says it's taken over by zealots, that the scourge of the Southern Democrats have entered into the Republican Party and that Goldwater is going to be the downfall of the Party. He goes into very colorful language about all of this; his descriptions of his experience there along with the descriptions of the other black Republicans there are fascinating. One man has his suit set on fire.

For Jackie Robinson in particular, he says, I can't bring myself to vote for or even endorse somebody like Barry Goldwater. As long as he's in the party, I will not be supporting the party in any way, shape or form. I will do everything I can for state and local but at the presidential level I'm going to campaign for Lyndon Johnson. So he becomes head of Black Republicans for Lyndon Johnson.

He also uses it as a jumping-off point to be one of the cofounders of the National Negro Republican Assembly, and I think it's really a watershed moment for black Republicans in general because this is really where they decide, are we just going to stand silently behind what our national leadership is telling us to do? Or are we going to strike out on our own and try to change the agenda of the Republican Party?

What I also find interesting is that Jackie Robinson explicitly says that any black person who supports Barry Goldwater and the Republican Party in this moment is an Uncle Tom, and [that he] won't accept any Uncle Toms in 1964.

Yeah, he wasn't shy in his use of rhetoric.

[Laughs] No, he was not. Not at all.

Goldwater tends to be seen by historians as a watershed moment for America, but in the popular imagination it's often Ronald Reagan who tends to loom very large. Is it accurate to place Reagan as prominently as people do when they try to identify the source of the GOP's Southernization?

I'd say that's true in 1984 but in 1980 it's a different ball game. I say that because we really look back at 1980 as the beginning of the Reagan Revolution. Reagan's entire campaign that year is brilliant in the way that it allows conservatism to become acceptable to the American public— and his strategists explicitly write about this. They say, we have to make conservatism something warm and soft and fuzzy and not scary and extremist. We have to make people want to be conservative without actually talking about the word "conservative." Even though I don't necessarily agree with how they go about doing that, that's a brilliant moment in American political history.

I think what happens in 1980 in particular is that we have this image of Ronald Reagan in terms of civil rights politics as being this figure who launches his campaign with that states' rights speech in Philadelphia, Mississippi — the site where, 16 years earlier, three civil rights workers are brutally murdered — and that's the Ronald Reagan we associate with civil rights.

What my research shows is that within three days of giving that speech he's speaking to the National Urban League. He goes and meets with Jesse Jackson and the black press uniformly applauds him for those actions. In fact, in some respects, they ignore the Philadelphia, Mississippi speech, and that just completely blew my mind because that's how we associate the Reagan moment.

What his strategists are trying to do is mitigate the effects, right? They say, we have to have two messages so that we can play up to white moderates, white conservatives, white liberals and we can appeal to them but we can also do things that maybe appeal to people of color. If we get them, great; if we don't that's all right too, as long as we win over moderates and liberals as well.

So they're doing some interesting work there and in some ways it works. One of the things that they set out to do is not have African Americans vote against them. They say, if we can get 10% of the black vote— which they do get— then we'll be okay. We don't need to get 30 percent, we don't need to get 40 percent, we just need black people to not come out and vote against us. One of the ways that they do this is by going out and appealing to African-Americans.

Why do you think it is that the black press was willing to overlook something that, from today's perspective, seems pretty horrid and impossible to ignore (Reagan's implicit endorsement of states' rights at its worst)?

One of the things I write about in the book is that legislative civil rights successes of the 1960s gave some African Americans the luxury ... of overlooking certain affronts. Whereas before they didn't have the protection of the law or the full force of the federal government behind them, by 1980 many of them do. We start to see the breakout of a black business class, the expansion of a black middle class and the black elite — which has always existed but is now growing much bigger — and what we start to see is that more and more African-Americans, even though they may not associate with the Republican Party are starting to look at it and say, Huh, maybe there are things in there that I identify with. If we can work out these racial issues and if I can actually like or tolerate Ronald Reagan, maybe I have more in common with him.

They're also attracted, in some regards, to some of his talk about business and free-market enterprise. Capitalism has had a long history in black liberal and conservative circles, so that's no surprise there. So when he starts talking about his Free Enterprise Zone, about lower taxes and things of that nature, African-Americans are attracted to that. Finally, I think some of these people like the idea of the American dream and meritocracy. It's a very attractive idea, this idea that there is a fair playing field.

One of the things Ronald Reagan learns from his experience interacting with African-Americans over a 30-year period between the 1950s and the 1980s is that one of the things they really respond to is him saying, I am not going to judge you by the color of your skin but by the content of your character and your skill. I see African Americans in position of prominence in my administration, in business, in other industries; lawyers, doctors. They really respond to that, I think, in a way that overshadows some of those other things that we look back on as being horrific.

The final thing I want to say about this is that Ronald Reagan is pretty good about speaking to African-Americans about states' rights in terms of local power and self-determination. When you have a few people who are ex-Black Panthers or who used to be part of the Black Power movement, hearing terms like "self-determination" and "community control" and "black-owned businesses" that is, again, really appealing to a segment of the population.

That makes sense, and it explains why the contemporary Republican Party still leans on that rhetoric even though it doesn't really work anymore.

[Laughs] Right, right.

There aren't that many prominent African-American Republicans, but obviously they do exist. How do you see figures like Colin Powell, Condoleeza Rice, Ben Carson? Are they qualitatively different from, say, Jackie Robinson?

Something I argue in the book is that the black Republicans we see today all come from a legacy of the characters I talk about in my research. They represent different strains, so somebody like Clarence Thomas is very much descended from the Lincoln Institute for Research and Education, from that tradition, or from the black silent majority. Somebody like Colin Powell or Condoleeza Rice is very much imbued with the tradition of an Ed Brooke.

We don't necessarily see somebody as fiery as Jackie Robinson but you do, on the ground, have black people who are liberal black Republicans in the tradition of Jackie Robinson. They may not be prominent, but one of the other things I talk about in the book is that the Party, traditionally, has given a platform to people who agree with its agenda. As the Party has moved more and more to the extreme, the people we see get platforms are going to be African Americans who identify with those specific tenets. So I do think there is very much a tradition where these people are pulling from strains, the various types of conservatism that I identify in the book.

Did you want me to mention the Ben Carson ... or talk about him a little bit?

Yes, by all means.

Something I identify with in the book that is not necessarily limited to electoral politics is this idea of respectability and there being a long, long strain of conservatism and respectability that goes back to the late 1800s, early 1900s. And Ben Carson is very much in that tradition; work hard, respectability, pull up your pants, put your hat on, dust your shoes off, bootstrapping mentality that is inherent to certain segments of African-American communities, especially middle class communities. So I see a lot of that with Ben Carson.

The other thing is that there is a certain segment of African-American communities that identify as conservatives. I mean this very much in the sense of, if you take the beliefs of the Republican Party, the most conservative aspects of the Republican Party, and line them up with this segment of the African-American community, it looks almost identical. Certain scholars in social sciences who have done some quantitative research on this have identified that number as being about 30 percent. When I hear that, I go, Whoa! That’s a huge number! But that number very, very rarely translates into votes or support for the Republican Party and that’s because there’s a breakdown over issues of racial inequality and civil rights.

Essentially, that most conservative group of African-Americans will not support Republicans because they think, even if their policy interests line up, they think the Republican Party will not support their racial interests. And so I think a figure like Ben Carson comes out of that, he is part of that segment that is incredibly conservative, whose policy preferences line up with the Republican Party, who maybe in the past may not have identified with the Republican Party. He may have identified with the Republican Party, but in recent years has become more outspoken and has become more explicitly Republican, identifying and aligning himself with the Republican Party.

So the last thing is, as you mentioned in the beginning, you drew some lessons. What were they?

So the biggest lessons that I drew away from this is over a 50 year period, you had Republicans of all ideological differences — these are hard, hard ideological differences — who were working within the same Party and able to forge partnerships and alliances in order to push common goals. So no matter how different these people are ... they’re able to work in these different strains in order to be productive. And sometimes that means bipartisan work, too. You really don’t see that in 2014, so I think there’s a lesson there about this idea of having an elastic or flexible definition of ideology. Politics should be pragmatic, we should be thinking about how to get things to work.

The other lesson I drew from this is that there’s a certain power in African-Americans swinging their vote, or being able to move with their vote, being able to push individuals. I think there’s something to be learned there not just for Republicans. Republicans have a lot of work to do, I mean an extreme amount of work to do, when it comes to the way that they use race and civil rights. It’s usually as a hammering ground, not in any kind of advocacy way. But there are also lessons for the Democratic Party. It’s important for them to see how black people are forging their electoral politics and what their interests are. One of the things that we’ve seen, and there have been a couple of people who have written about this, is the way in which African-Americans become disillusioned with politics and with the Democratic Party, and end up abstaining from voting altogether. That’s something that actually hurts the Democratic Party. It would especially be hurtful if they then turned to the Republican Party, but either way that ends up benefiting Republican politics, so I think there’s something to be learned from that as well.

I think one of the other lessons that I really took away from this is that there’s something exciting about thinking beyond the boundaries of traditional liberalism/conservatism split and thinking about solutions for the nation’s most pressing problems outside the landscape of what an ideology dictates that you do. That to me is really exciting, especially as we think about political ideas going forward. A lot of the people that I looked at and studied, both on the Republican and the Democratic side, threw labels away and were interested in moving labels apart. This includes figures like Democratic congresswoman Shirley Chisholm, who actually hired, as one of her policy advisors, a black Republican. So that to me is real, forward thinking, progressive thought. So what are the kinds of policies that we’re going to use regardless of our ideological affiliations that are are going to move our society forward and be in the best interest of the nation, and in this case, African-American communities?

Shares