Publishers can be excused for making claims that their new title is "the next 'Da Vinci Code'" or "the next 'Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.'" They're just doing their job -- that is, coaxing readers into buying the books they thought well enough of to publish. (Oddly, the very people who gripe about such marketing gambits tend to be the same ones who complain when their own books aren't aggressively marketed.) When the press jumps on the bandwagon, however, it's another matter.

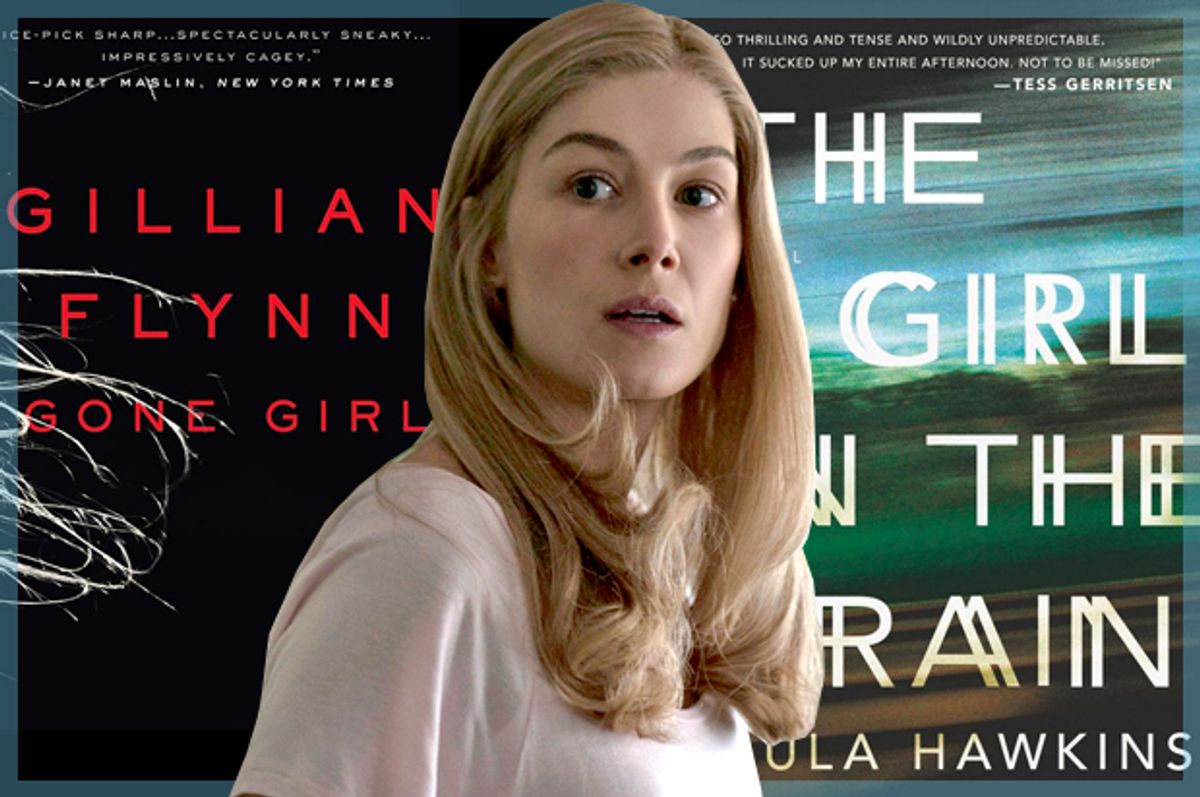

Publications ranging from the New York Times to USA Today and the Wall Street Journal are currently touting "The Girl on the Train," a new psychological suspense novel, as "the next 'Gone Girl.'" And I suppose they're right, to the extent that "The Girl on the Train," by the relatively unknown Paula Hawkins, is a bestseller, a status it attained largely on the strength of being dubbed the next "Gone Girl." "The Girl on the Train" isn't even the first novel to enjoy such a bump; two years ago, "The Silent Wife" by A.S.A. Harrison climbed the charts after being likened to "Gone Girl" in some of the same publications.

And yes, all three of these books concern marriage: its illusions, disappointments, treacheries and persistent allure, particularly for women. But while both "The Silent Wife" and "The Girl on the Train" are fine examples of their genre -- psychological suspense typically features a story of crime or peril centered on the characters' often unstable emotional states -- they otherwise have little in common with Gillian Flynn's mega-bestseller. Claiming that they do just sets readers up for disappointment.

Still, the comparison helps illuminate the extraordinary qualities of Flynn's novel, one of those rare instances when a daring and genuinely literary genre title gets the success it deserves. "Gone Girl" can be read as an entertainingly tricky thriller, full of dark schemes and outrageous plot twists, and nothing more. (I have one friend who dismisses it as a "great beach read.") But it's also a work of acute and slicing social satire, so that readers who don't especially treasure its narrative gymnastics will praise it for, in particular, its celebrated "Cool Girl" rant about the futility of women trying to fulfill the pop-culture-fueled expectations of young men.

By contrast, "The Girl on the Train," while diverting, never offers more than the reliable gratifications of its genre. The main character, Rachel Watson, is divorced and alcoholic, riding the train into London every day in order to conceal from her flatmate the fact that she's lost her job. The train passes the street where she used to live and where her husband still lives with his new wife and baby. In its often halting progress, the train also offers Rachel a view of the back of another house on that street, and she conceives an idealized fantasy life for the handsome young couple she often observes there, sipping coffee in the mornings and wine in the evening. Then she sees something that undermines those fantasies, and after that the wife in the couple goes missing. Rachel tries to offer her information to the investigation but because she's known to be a drunk obsessed with her ex, no one takes her seriously.

Hawkins executes this story skillfully, by which I mean that she juggles the readers' ever-shifting suspicions about what really happened to the missing woman, keeping various possibilities in the air until the final fourth of "The Girl on the Train." As Stephen King observed on Twitter, the novel's best element is its depiction of Rachel's alcoholic haze and her sheer terror at not knowing or understanding what she's done during her binge-induced blackouts.

Nevertheless, the other characters in "The Girl on the Train" have the bland, burnished quality of cogs built to serve a purpose rather than actual people with real lives that transpire in the real world at a particular place and time. Here's how Rachel views "Jess," as she has named the young wife she scrutinizes through the train window:

Jess, with her bold prints and her Converse trainers and her beauty, her attitude, works in the fashion industry. Or perhaps in the music business, or in advertising --she might be a stylist or a photographer. She's a good painter, too, with plenty of artistic flair. I can see her now, in the spare room upstairs, music blaring, window open, a brush in her hand, an enormous canvas leaning against the wall.

And here is how Flynn has Amy Dunne describe the party where she meets Nick, the man she will marry:

We climb three flights of warped stairs and walk into a whoosh of body heat and writerness: many black-framed glasses and mops of hair; faux western shirts and heathery turtlenecks; black wool pea-coats flopped all across the couch, puddling to the floor; a German poster for The Getaway (Ihre Chance war gleich Null!) covering one paint-cracked wall. Franz Ferdinand on the stereo: “Take Me Out.”

Besides the greater vivacity and alertness of Flynn's prose, where Hawkins is vague ("plenty of artistic flair"), Flynn is precise, plucking details from the crowd that locate them within a specific hipster milieu. Even if you don't quite get the cultural brand names, you know what it means that the hosts live in a walk-up with warped stairs and cracked walls, and that they've put up a German poster for an American movie. This is partly because Amy herself is such an astute observer of how the people around her position themselves socially, but then Rachel is supposed to have worked in a big-city public relations firm, so she's hardly a suburban naif; she should know and notice this stuff. Not that "The Girl on the Train" gives the reader any sense at all of what Rachel's work life might have been like. All of the characters' jobs are invoked with the dutiful rigor of the professional affiliations listed in newspaper articles ("Tom, 45, an IT specialist...").

The thin texture of Hawkins' novel isn't necessarily a flaw. One of the attractions of standard genre fiction is that it doesn't demand too much attention to anything more than the core basics of the story. You don't have to decode all those little signifiers or pause to admire (however queasily) a reference to "a supermarket deli tray full of hoary carrots and gnarled celery and a semeny dip," let alone think about what kind of woman would make such a comparison. You can zip through a series of streamlined, familiar sentences (akd, clichés that would set a literary critic's teeth on edge), without too many distracting ambiguities or a lot of scene-setting. It's hard to conjure up an image of the Blenheim Road, the site of so many of Rachel's fixations, but there are plenty of readers who won't miss that a bit.

And unlike "Gone Girl," most suspense novels don't play cat-and-mouse with both their readers and the genre itself. (Here's where I need to discuss some of the plot twists of Flynn's novel, so if you don't want to read that, make yourself scarce.) Flynn's narrative is an elegant meta puzzle box in which the reader is at first shackled to two average people -- the squirrely Nick and the fake, innocent Amy who narrates the diary the real Amy concocts to incriminate him -- hapless victims of circumstances and forces like the economy, the media and the criminal justice system, all well beyond their control.

At the midway point of "Gone Girl," the real Amy's voice breaks in, revealing that she has, through superhuman ingenuity and commitment, been the master and designer of everything we have seen so far. Her machinations include not only decanting a pool of her own blood to leave at the supposed scene of the crime, but also carefully establishing, over the course of year, the false impression that she is afraid of blood. This Amy is a monster, but she's powerful, and the reader experiences an exhilarating rush at suddenly finding herself attached to such a commanding narrator. (One of the few smart touches of David Fincher's embalmed film adaptation of the novel is to reveal Amy's true nature in a scene that shows her roaring down a highway in sunglasses, the visual embodiment of Nietzschean freedom.)

Amy is not "likable," but then again she's the villain. "Gone Girl" concludes with Nick decisively confined in her trap, put in the position of pretending to be her doting husband for the foreseeable future. "I want to be married to a normal person," he protests, but Amy doesn't buy it. "You think you can ever be a normal man again?" she asks. "You’ll find a nice girl, and you’ll still think of me, and you’ll be so completely dissatisfied, trapped in your boring, normal life with your regular wife and your two average kids." As demented as this sounds (and some readers find Flynn's conclusion excessively dark), Nick soon realizes that she's right. No ordinary woman would or could do as much to possess him as Amy has, and eventually such a woman would come to seem "substandard" by comparison.

Nick says he wants a normal wife the way the readers of books like "Gone Girl" say they prefer likable, morally comprehensible characters. Amy and Flynn call bullshit on that. If you wanted to read about decent people going about their relatable lives, you'd be reading literary fiction by writers like Alice Munro or Alice McDermott. When it comes to thrillers, we may end up identifying with the hero, but he's not why we turn up in the first place, and not what many of us remember. It's Hannibal Lecter, not Clarice Starling, who keeps Thomas Harris' fans coming back for more. It often seems like the villain's inevitable defeat at the end of the story is merely a fig leaf to cover the pleasure we get from seeing him do his worst up to that point.

That many readers tacitly or even overtly identify with a great villain is not exactly a revelation; critics remarked long ago that Satan is the only truly interesting character in "Paradise Lost." But most commercial crime fiction refuses to acknowledge this, presenting a Potemkin Village of moral uprightness while indulging its audience's evident hunger for blood, guts and clever, sadistic serial killers.

Of course, it's possible to read "Gone Girl" as purely the story of one such bad guy -- or, in this case, bad girl -- and to be perturbed that Nick never gets free of Amy in the end. Fincher's film more or less takes that view of the story and hundreds of thousands of readers have enjoyed Flynn's novel on this level, like any other work of psychological suspense, before moving on. Look deeper, however, and you can find a lot more: sharp prose, scathing satire of contemporary gender roles, bravura manipulations of narrative technique and an interrogation of the thriller form itself. These are qualities you almost never come across in the genre, and the real reason why we won't be seeing the next "Gone Girl" any time soon.

Shares