Maybe it’s just a sign that I’m especially negative, but I’ve long felt that one of the more common ways we try to get to know one another, by asking about our passions and favorite pieces of identity-defining entertainment, is misguided. It’s backward, in fact. Instead of finding out what someone likes, asking what they dislike is a much better way to get a rough sense of their personality.

For example: If I asked you to name a band or movie you love, and you answered with the Beatles or “The Godfather” — or some other piece of pop culture that enjoys near-universal acclaim — that wouldn’t really tell me much about you. But if I tweaked the question and asked you what you hate, and you answered with Sly & the Family Stone or “Toy Story,” that could, potentially, tell me quite a bit. (In this case, I’d know that you’d likely prefer I maintain a respectful distance from your lawn.)

It’s a crude and imperfect system, of course; and in a better world we’d all try to approach one another as full, complex human beings rather than as merely the sum of our aesthetic preferences. Sadly, that is definitely not the world we live in, and there’s a real value in having a framework that can help us decide how to expend our finite amounts of energy and time. Allow me, therefore, to submit the following: In a limited and caveat-ridden way, we are what we hate.

The reason I’ve had all of this on my mind lately (besides my turning into a millennial Rob Gordon, which is always ongoing) is because I’ve started wondering what we might learn about the electoral bases of the Republican and Democratic parties if we saw each through this lens. And if we look at two recent examples of hate-figures making headlines — the Koch brothers for the left, and “illegals” for the right — I think we’ll find that the antipathy of each respective party’s base may be similar, but are decidedly not the same.

Starting on the left, it’s rather obvious that if diehard Democrats could choose just a handful of people to send on a one-way trip to Mars, the Koch brothers would be among them. When news of the Koch brothers’ plans to raise nearly $1 billion for the 2016 elections first broke, the response from Democrats was apoplectic. The folks at Daily Kos described the billionaire conservatives as super-villains (sometimes with a respectful contempt, other times with mockery), union foes likened them to the evil Empire from “Star Wars,” and Democratic operatives, who know well that anger and fear tend to inspire more donations than sunnier feelings, quickly went to work using the Kochs to fundraise.

Yet while these examples clearly show how thoroughly the Kochs have been demonized among Democrats, the charges actually leveled against these GOP moneymen were relatively mild (as always, social media was a different story). More important, they focused on things the Kochs were actually doing: “trying to buy the election,” as it was usually put. According to the framing used by the vast majority of Democrats, the Kochs weren’t deserving of scorn because of who they were, but because of what they did — and the antipathy wasn’t based on speculation, but rather articles from countless reputable media outlets.

But if we jump ahead a week and shift our focus to the right, the dynamic is quite different. As you’re probably aware, the vaccination controversy has tripped up some big-name Republicans as of late. Because the anti-vaccination movement often uses the rhetoric of freedom from overweening government and undemocratic control, many non-conservatives reflexively assume the anti-vaxxers are right-wing (the truth is more complicated). Predictably, many rank-and-file members of the GOP base — as well as some high-profile right-wing media figures and politicians — have consequently tried to shift the blame for a recent measles outbreak away from themselves and toward one of their usual targets: undocumented immigrants (or, as they prefer to call them, “illegals”).

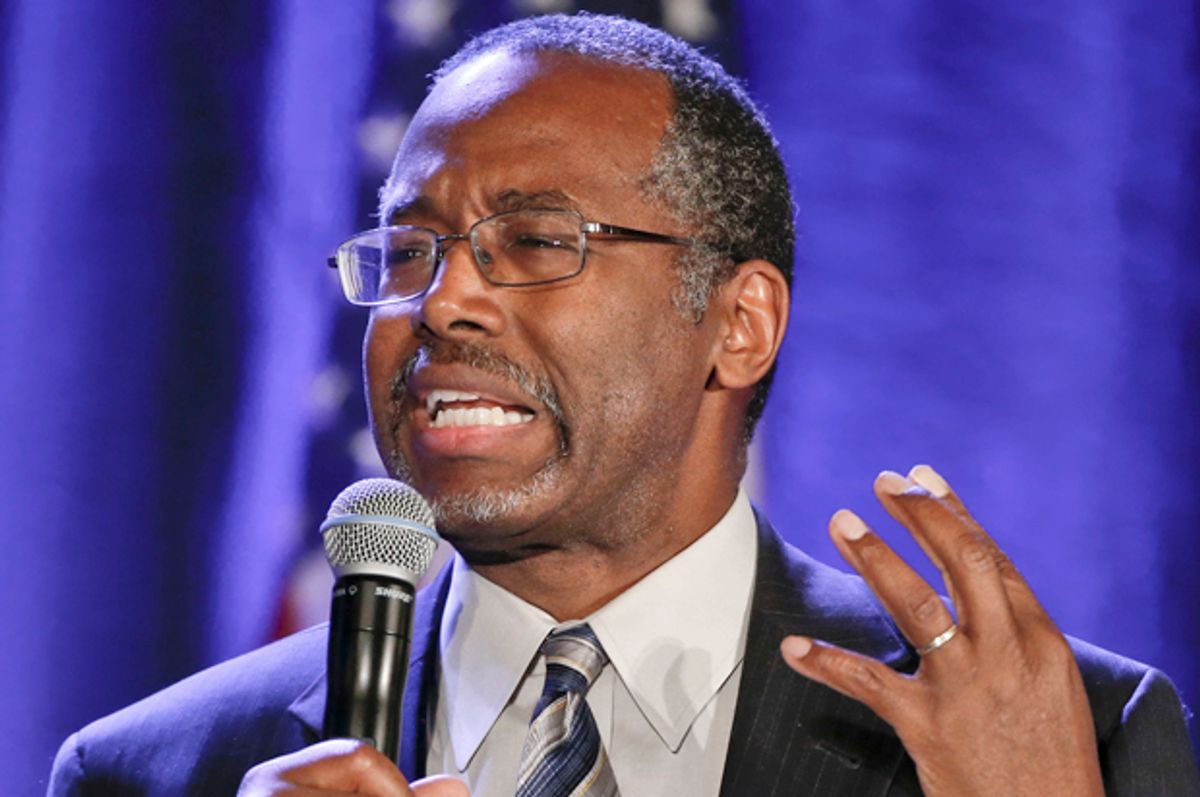

And this is why we’re seeing conservative superstar Ben Carson speculate on CNN that “undocumented people who perhaps have diseases that [the U.S.] had under control” are to blame, not opponents of vaccinations. It’s why we’re hearing Alabama Rep. Mo Brooks make the same allegation on right-wing radio, wondering “who can honestly say that Americans have not died because the diseases brought into America by illegal aliens who are not properly health care screened.” It’s why we’re witnessing conservative pundits like Betsy McCaughey and J.D. Hayworth inform their audience that it’s immigrants who are to blame — and not just illegal ones, mind you; McCaughey says “immigration of all sorts” is part of the problem.

Yet unlike the lefties who hate the Kochs, the conservative impulse to blame immigrants for public health scares is completely untethered from any factual basis. As we found out last summer, when right-wingers started blaming immigrants (including migrant children) for Ebola, most immigrant children come from countries where the vaccination rate is north of 90 percent. According to Irwin Redlener, co-founder of the Children’s Health Fund and Columbia University pediatrician, “The primary care system in developing countries is more effective than in the U.S. — better than people think.”

The right’s theory may be superficially plausible, in other words, but it’s severely lacking empirical heft. You’d expect that to be a real hindrance to the meme’s proliferation. But here’s the thing, and it’s one of the places where the difference between Democrats and Republicans is most stark: For many members of the GOP base, it’s the very nature of undocumented immigrants that makes them a threat. It’s who they are. Any threat in particular, whether it’s disease or crime or flatlining wages, can be attributed to them. Identity, not action, is what matters; the charges precede the crime.

None of this is to say that Democrats are incapable of harboring irrational negative feelings, or that Republicans have a monopoly on angry tribalism. People are people. What it does show us, though, is how much more central group solidarity and shared identity is to conservative diehards. To understand them fully, you’ve got to really listen when they tell you what they hate.

Shares