Gary Hart had one more move. It was Sunday, July 15, 1984, the eve of the Democratic National Convention, in San Francisco. He had won the California primary on June 5, seven of the last 11 contests, and more overall than frontrunner Walter “Fritz” Mondale. But Hart was way behind in delegates. Mondale had announced he had enough to be nominated to oppose incumbent Ronald Reagan in the fall. Hart had neither conceded the race nor suspended his campaign.

“Surprises could happen,” Hart recalled to Salon in an interview for this article.

Staying at the old St. Francis Hotel in Union Square, Hart walked across the square to the Hyatt to visit Reverend Jesse Jackson. Jackson had been as much of a revelation as Hart in the primaries and became the first black candidate to mount a very competitive White House run, finishing third in delegates.

“I sat outside Jesse’s door for about half an hour, and finally he let me in,” Hart said. “I wanted him to endorse me and turn his delegates over to me.”

Hart was polling 10 points better than Mondale against Reagan. A deal with Jackson could elevate him closer to Mondale’s delegate total but still short of a majority. “That would have gotten me up to 1,500 and some, and who knows what would have happened then,” Hart said.

Jackson wasn’t ready to quit. He wanted to be officially nominated for president. “Any idea of placing the delegations together went out the window, but at least I made a try,” Hart said.

Suspense over the nominee is only one factor that distinguishes the 1984 Democratic National Convention from all 15 major party conventions that have followed. There were also historic candidate breakthroughs by race, gender and generation. There was a most memorable keynote address. There were fights over the party platform. It was the first time there were “super” delegates -- office holders and party activists who can play a decisive role in the nomination. And there was a huge television audience. Subsequent conventions might have one of these elements, but none had them all, and the gatherings in Cleveland and Philadelphia next summer probably won’t compare to the Democrats in 1984 either.

“Everything was still up in the air. We were shaping policy,” Mondale told Salon in an interview for this article. “We were calling super delegates. We were trying to get everybody committed.”

“It was exciting, because no one exactly knew how it was going to come out,” Jackson said in an interview for this article. “Now we have cookie cutter conventions – you buy the bread already packaged, or you just heat it up. There we made the bread on the spot.”

###

Only nine years apart, Mondale, then 56, and Hart, then 47, were of different generations. Mondale was a New Deal-nurtured, Great Society liberal who spent two terms in the Senate. Like the mentor he succeeded, Hubert Humphrey, Mondale was out front on civil rights, for example, as lead Democratic sponsor of a 1968 fair housing law that prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of homes. Mondale served as Jimmy Carter’s vice president from 1977 to 1981, until Carter vacated the White House for Reagan. With Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy forgoing a 1984 run, after challenging Carter in 1980, the party establishment closed ranks around Mondale.

Hart, a JFK and RFK acolyte, had managed George McGovern’s insurgent 1972 presidential campaign and arrived in Washington in 1975 as a member of the reform-minded congressional class of 1974, Democrats elected in a wave of Watergate discontent with Republicans months after President Richard Nixon had resigned. Hart relished breaking with party orthodoxy, such as when he opposed the 1979 Chrysler bailout.

In 1980, when nine Democratic incumbent Senators were swept out of office in the first Reagan election – including McGovern, of South Dakota; Frank Church, of Idaho; Birch Bayh, of Indiana; and Gaylord Nelson, of Wisconsin – Hart survived. Democrats in other states, like Nebraska gubernatorial hopeful Bob Kerrey, started inviting Hart to campaign for them.

In 1983, Mondale racked up endorsements from labor and teachers’ unions, women’s groups, environmentalists and politicians, but only half of Democrats polled said they would vote for him in primaries.

“What I saw was 50 percent of the Democratic voters looking for a different kind of candidate,” Hart said. “It wasn’t that they were opposed to Mondale or found anything wrong with him, particularly, it was a search for new leadership, and that propelled me into the race.”

When almost nobody owned a computer, Hart talked about technology, the information revolution, globalization, and a post-Cold War foreign policy. Reduced to a slogan, this was his New Ideas.

“That wasn’t just image. That was a sense that the traditional New Deal message, which conservatives reduced to ‘tax and spend,’ had partly run its course. What activist Democrats were looking for was a way to support the social safety net by accommodating to changes going on in the economy,” Hart said.

Mondale’s motivation stirred from the moment in 1981 when Reagan stated in his inaugural address, “Government is the problem.”

“Reagan was a very radical new voice in American life, and he really wanted to tear down good things we thought we’d accomplished, and we hoped that would help us defeat him,” Mondale said.

Candidate Reagan had promised to cut taxes and erase the $79 billion annual federal budget deficit left by Carter. Instead, lower income taxes and greater military spending caused the deficit to balloon to $208 billion in 1983. Mondale wanted to reduce the deficit and reset priorities for education, health care and the environment.

“The idea that there is some magic compelling reality that you can never increase a government program of any kind – can’t do it – and you can’t raise taxes to do it, that is anathema to me,” Mondale said.

Mondale easily won the first-in-the-nation Iowa caucuses, on Feb. 20, 1984, but Hart finished second, gaining notice and momentum, and then won the first primary, in New Hampshire, in a stunning upset eight days later.

“We stumbled quite a bit after that,” Mondale said, “And it took us a while to get our feet underneath us.”

The other “Anybody But Mondale” candidates, including space hero John Glenn, then an Ohio Senator, never gained traction or won a single primary or caucus. Mondale and Hart traded victories for four months. Mondale won in Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Pennsylvania and Texas. Hart won in Nevada, Florida, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Ohio and Indiana. Meanwhile, Jackson won in Louisiana, South Carolina and Washington, D.C., capturing at least 20 percent of the vote in eight states.

Overall, Mondale won 7 million votes, or 38 percent. Hart won 6.5 million votes, or 36 percent. Jackson won 3.3 million votes, or 18 percent. Democratic rules had shifted from “winner take all” primaries to “winner take more” primaries whereby winners earned an extra delegate in each district where he was the top voter getter. This helped Mondale. So did the 550 super delegates; four out of five were for him.

Heading into the convention, Mondale was only slightly worried the nomination would slip from his grasp. “I had some concern, but I could figure out how I could get there. I was more worried when I lost New Hampshire,” Mondale said.

On June 6, a day after he lost the California primary but won in New Jersey and West Virginia, Mondale announced at a St. Paul news conference, “I will be the nominee.”

That day Mondale claimed he had 2,008 delegates pledged to him, or 41 more than the magic number of 1,967 needed to nominate.

“There were a lot of uncommitted delegates who I thought would be with me at the convention, and I just had to call them and urge them to speed it up for me,” Mondale said.

Hart had a more difficult time working the phones. “My wife and I called every super delegate. I don’t think we got one super delegate, and that was the difference.”

Some told Hart and his wife, Lee, it was politically impossible to switch sides. He said, “One woman from a Southern state said to my wife, ‘Look, I love your husband. I wish I could vote for him. But my husband works for the state highway [department], and I’ve been told if I don’t vote for Mondale, he’s going to lose his job.’ There was a lot of strong-arming going on.”

Two weeks before the convention, Mondale and Hart had their first post-primary sit-down, in Manhattan. “The things that divide us are modest compared to the things that divide us from President Reagan,” Mondale told reporters. They shared a “profound fear of a second Reagan term,” Hart added. Unity did not necessarily mean Mondale would offer Hart the vice presidential nomination. Hart quipped Mondale was on his Veep list.

###

Mondale’s running mate search included African-Americans, Hispanics and women paraded to Minnesota – Mayors Diane Feinstein, of San Francisco; Henry Cisneros, of San Antonio; Tom Bradley, of Los Angeles; and Wilson Goode, of Philadelphia. White men were also interviewed, such as Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis and Texas Senator Lloyd Bentsen. Halfway through the vetting, Mondale was disappointed. “I think it looked like a cute routine,” he told me. “It could have been easier to manage privately.”

Tip O’Neil, the Democratic Speaker of the House of Representatives, had steered Mondale toward three-term congresswoman Geraldine Ferraro of New York City. She was 48, Catholic, daughter of an Italian immigrant, and had previously worked as a teacher, a prosecutor, and stay-at-home mother of three. As a sign of her bipartisan appeal, Ferraro boasted she represented Archie Bunker’s district, the Queens location where the fictional conservative star of TV sitcom "All In The Family" lived.

“Tip O’Neil told me, ‘Take a look at Gerry. She’s really very well respected here. She is a very effective congresswoman. She’s someone you ought to seriously think about putting on the ticket.’ And I got that from others,” Mondale said. “She could play with the big boys.”

When Ferraro went to Washington, in 1979, she was one of only 16 women in the House, and there was only one woman senator. Ferraro wrote laws permitting “flex time” for federal employees and creating retirement accounts for homemakers and single mothers. She sponsored a bill requiring employers to grant unpaid family leave, which finally became law under President Bill Clinton. Ferraro envisioned rising in House leadership or running for Senate in 1986.

“She wasn’t thinking beyond that. She loved being a member of Congress,” Donna Zaccaro, the eldest of Ferraro’s three children with real estate developer John Zaccaro, said in an interview for this article.

Thanks to O’Neil, the party appointed Ferraro to chair the convention’s platform committee crafting the party’s vision. “It was a big deal back then,” Zaccaro said. “It’s also how she really learned about all the issues all around the country. That really was her prep, which was fortunate.”

Ferraro emerged with a handful of women talked about as possible running mates. She and Feinstein graced a Time magazine cover asking, “Why Not a Woman?” The National Organization for Women, which had endorsed Mondale, passed a resolution calling for a woman on the ticket. Ferraro told friends she did not believe a man would pick a female running mate unless he was 15 points behind in national polls. Mondale was.

###

Jesse Jackson’s base had been Chicago since Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference dispatched him there in the mid-1960s to oversee a black business development and jobs program called Operation Breadbasket. Jackson worked with King from Selma to Memphis, where King was assassinated in 1968. Jackson broke with the SCLC in 1971, became an ordained Baptist minister, and started his own justice and empowerment organization, People United to Save Humanity.

After Jackson helped Harold Washington win election as Chicago’s first black mayor in 1983, he started musing about recruiting a black candidate to run for president in 1984. Fellow civil rights pioneers, like Atlanta Mayors Andrew Young and Maynard Jackson, turned him down. There were no black senators or governors to consider. There were 22 black representatives in the House of Representatives, and black mayors ran Birmingham, Charlotte, Detroit, Newark and New Orleans. But no candidate emerged.

Speaking at voter registration drives, Jackson, then 42, heard crowds chant “Run, Jesse, Run!” When he heeded the call and entered the presidential race himself, Jackson labeled his following the Rainbow Coalition.

“The Rainbow really is America – a multiracial, multicultural coalition,” Jackson said. “It was a crusade for change, and we took unpopular, not poll-driven, positions on issues.”

Jackson called for tougher enforcement of the Voting Rights Act, affirmative action in hiring and college admissions, gay rights, a Palestinian state and ending apartheid in South Africa.

“We were raising issues that had not been raised – for example, Free Mandela. At that time, he was on the terrorist list,” Jackson said.

At the height of the Reagan military buildup, Jackson advocated real cuts in Pentagon spending and applying the savings to domestic programs.

“Dr. King’s point was we shifted the War on Poverty resources to the War in Vietnam. He said bombs dropped in Vietnam explode in American cities, metaphorically speaking,” Jackson said. “And to be certain, we’ve stayed right there.”

Jackson appealed beyond his urban base to distressed farmers in Iowa, coal miners in West Virginia and Campbell’s Soup workers in Ohio. He overnighted on Native American reservations and in the homes of people with AIDS shunned by their families.

“I had no doubt that there had been more people locked out of the process than had been previously considered,” Jackson said.

His vote total ranged from a low of less than 1 percent in Maine to highs of 20 percent in Alabama, 21 percent in Georgia, 25 percent in South Carolina and 34 percent in Arkansas. He dominated the black vote – winning 50 percent in Alabama, 61 percent in Georgia, 77 percent in Pennsylvania and 87 percent in New York.

Jackson won among black voters younger than 50, but Mondale won the older ones. “They had adjusted to their predicament,” Jackson said. “Those who want change must be maladjusted.”

Jackson had attended national conventions since the 1960s, but the San Francisco convention at the Moscone Center was different for him and the movement.

“We used to go to conventions and try to get notes to candidates back in their trailers. We had our own trailer for the first time, and our floor plan for the first time, our own whips on the floor for the first time,” Jackson said.

Jackson tried to change Democratic Party rules – to make presidential primary delegate allocation more proportional to vote totals and to get 10 Southern state parties to repeal primary runoffs triggered when no candidate achieved 50 percent of the vote. Jackson argued those runoffs disadvantaged a black candidate who might come in first, because voters tended to coalesce around a white candidate in a runoff, sending a black candidate to defeat.

“We were fundamental to change – democratizing democracy, democratizing the rules, democratizing access to the process,” Jackson said.

As the convention neared, the Jackson and Hart campaigns targeted 250 Hispanic delegates and 400 black delegates ostensibly pledged to Mondale. Had 100 of them agreed to switch their votes to Hart or Jackson or simply to abstain on the roll call, it could thwart a first ballot nomination for Mondale.

“It wasn’t a threat to me,” Mondale said. “The delegates I had who were black were for me. It wasn’t about color; it was about my position in civil rights, which, I think, was as solid as it could be.”

###

On Sunday night, July 11, a week before the convention, Ferraro was in San Francisco to chair platform hearings. She was in her room at the Hyatt Regency Embarcadero when she got the phone call.

“Will you be my running mate?” Mondale said.

“That would be terrific,” she replied. “I want you to know, Fritz, I am deeply honored.”

Donna Zaccaro, then 22 and working on Wall Street, was in her Manhattan apartment ironing her outfit for the next day. “She called each of us,” Zaccaro said, referring to her brother, John, 20, who was in Hawaii, and her sister, Laura, 18, who was at home with her father.

“It was a total shock. We knew she was being considered, but we never thought it was really going to happen,” Zaccaro said. “We all knew that everything was going to change.”

The Mondale campaign snuck Ferraro out of her hotel for a late-night charter flight from Oakland – a better chance to take off undetected than from San Francisco – to Minnesota for the next morning’s announcement.

“This is an exciting choice!” Mondale told the cheering crowd inside the state capitol. He intended to shake up the race and lock in his victory.

“It quieted all challenges to the nomination,” Mondale said. “All the polls showed me in bad shape, and I knew I had to do something to reshuffle the deck, to open things up, to have a more energetic and courageous approach to the election.”

Zaccaro said of her mother, “She was the first one to say, I would never have been chosen if my name was Gerard Ferraro. She recognized that she was chosen because she was qualified, but she also was a woman.”

###

Convention opening nights featured a thematic keynote address, and on Monday, July 16, the Democrats tapped first-term New York Governor Mario Cuomo, 52, who had a reputation for eloquence. Cuomo’s words were like daggers directed at Reagan’s tale of America, which Cuomo reimagined as a Dickensian tale of two cities.

''A shining city is perhaps all the president sees from the portico of the White House and the veranda of his ranch, where everyone seems to be doing well,'' Cuomo said. ''But there's another part to the shining city. In this part of the city, there are more poor than ever, more families in trouble, more and more people who need help but can't find it.''

He challenged Reagan to visit unemployed steel workers in Buffalo or people living in homeless shelters in Chicago. Speaking to him directly, Cuomo said needy families could not get help to feed their children, because “You said you needed the money for a tax break for a millionaire or for a missile we couldn’t afford to use.”

In contrast to his articulation of compassionate liberalism, Cuomo said Republican policies “divide the nation into the lucky and the left out, into the royalty and the rabble.”

He argued the Democratic Party was a better defender of the middle class -- “the people not rich enough to be worry free but not poor enough to be on welfare… those who work for a living because they have to.”

Cuomo decried the president’s “trickle down” economics, which theorized tax cuts for the highest earners would spur economic growth. He said the recovery from the 1982 recession was paid for by “bankruptcies, unemployment, and the largest government debt known to humankind.”

Reconstructing a line from Reagan’s inaugural, Cuomo said, “We believe in only the government we need, but we insist on all the government we need.”

He criticized the “macho intransigence” of the Reagan defense buildup that presumed the nation could “pile missiles so high that they will pierce the clouds, and the sight of them will frighten our enemies into submission.”

Democrats believed in an affluent society that “can spend trillions on instruments of destruction ought to be able to help the middle class in its struggle,” Cuomo declared.

He concluded by celebrating the saga of immigrant families like his and Ferraro’s, whose hard work and commitment to education enabled them to ascend from pennilessness to the middle class in one generation.

During his 40 minutes at the podium, interruptions for applause were frequent and sustained. CBS News anchor emeritus Walter Cronkite commented how the entire hall was quiet, listening all the way through. Commentator Bill Moyers called the speech “brilliant.”

Years later, while still in office, Cuomo told C-SPAN the convention delegates had been “desperate to hear something that would make them feel good about themselves, about the party, about the country, and about possibility.”

“Whatever pictures I chose worked for them,” Cuomo said. “The message and the moment came together.”

###

On the convention’s second day, Tuesday, July 17, after four hours of floor debate, the party adopted its 45,000-word platform. It was mostly a Mondale document calling the budget deficit “intolerable” and pledging to reduce it without a Constitutional Amendment requiring a balanced budget every year. The platform vowed to “reassess” defense spending and promised to protect Social Security. It supported nuclear arms control, gays serving in the military and ending military support for Nicaraguan anti-communist rebels.

Hart and Jackson had pushed their planks to the end. Hart’s “peace plank” stated a Democratic president would not “hazard American lives or engage in unilateral military involvement,” such as in Central America or the Middle East, unless there were clear objectives and diplomatic leverage had been “exhausted.” It was approved.

Jackson’s “no first use” plank, saying the U.S. would never launch nuclear weapons first against the Soviet Union or anyone else, was defeated. So was Jackson’s hope to ban those runoff primaries in the South. Jackson won a compromise on affirmative action, when the platform called for “timetables” (but not quotas) to end discrimination in employment and education.

Back when a “prime time” speaking slot meant a lot, the second evening belonged to Jackson. He took the stage with his wife and their five children and an entourage of supporters.

“Just 20 years ago, Jesse Jackson was leading demonstrations demanding the right to eat at the Woolworth lunch counter,” ABC News anchor David Brinkley told his audience.

“My constituency is the desperate, the damned, the disinherited, the disrespected and the despised,” Jackson began. “They've voted in record numbers. They have invested faith, hope and trust that they have in us. The Democratic Party must send them a signal that we care.”

Behind the scenes, Jackson had joined Hart’s attempt to persuade minority delegates pledged to Mondale to defect and deprive Mondale of an easy win. With 12 percent of the delegates, Jackson now called on them to ratify their support.

“I ask for your vote on the first ballot as a vote for a new direction for this party and this nation. A vote of conviction, a vote of conscience,” Jackson told the crowd. “But I will be proud to support the nominee of this convention.”

Looking toward the future, Jackson expounded on the idea of the Rainbow Coalition.

“Our flag is red, white and blue, but our nation is a rainbow -- red, yellow, brown, black and white -- and we're all precious in God's sight,” Jackson said. The nation, as he saw it, was a quilt -- “many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread.”

Jackson continued, “The white, the Hispanic, the black, the Arab, the Jew, the woman, the native American, the small farmer, the businessperson, the environmentalist, the peace activist, the young, the old, the lesbian, the gay, and the disabled make up the American quilt.”

He recapped the African-American journey that led to his place at the podium, from slavery to emancipation, from Jim Crow to the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts, and then enduring the assassinations of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and the Kennedys. He invoked two white Jewish men from New York, Mickey Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, and one black Mississippian, James Chaney, who were murdered and buried in the Mississippi mud during the 1964 Freedom Summer voter registration drives. He mentioned a less well-known “Viola,” referring to Viola Liuzzo, a white woman from Michigan ambushed and killed by the Ku Klux Klan as she drove home after assisting the marches for voting rights in Selma, Alabama, in 1965.

“The team that got us here must be expanded, not abandoned,” Jackson said. “We are bound by shared blood and shared sacrifices.”

Jackson denounced Reagan’s doubling of defense spending in peacetime, cutting taxes for the rich and government programs for the poor, and racking up a budget deficit greater than the sum of all prior deficits from George Washington through Jimmy Carter.

“Rising tides don’t lifts all boats, particularly those stuck on the bottom,” he said.

Jackson built to a crescendo with repetition of the phrase “Our time has come” and a reference to the Statue of Liberty inscription: “We must leave racial battleground and come to economic common ground and moral higher ground. America, our time has come. We come from disgrace to amazing grace. Our time has come. Give me your tired, give me your poor, your huddled masses who yearn to breathe free, and come November, there will be a change, because our time has come.”

His family and entourage rejoined him on the stage. Some were clapping and chanting “Win, Jesse, win!”

Afterward, Jackson told me, “People came up to me crying about how they had never seen a black man speak of substance on TV before.”

CBS News Anchor Dan Rather remarked more Americans saw Jackson’s speech than the broadcast of King’s “I Have Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington.

“That was just a phase of our struggle,” Jackson said. “I think it changed their minds of what was possible.”

###

Democrats had to look back to 1952 – and Republicans to 1948 – to find a convention that failed to pick its presidential candidate on the first ballot. But on the third day in San Francisco, Wednesday, July 18, Hart thought there was still a chance to deny Mondale a first ballot nomination. But he left the work to Jackson.

That morning Mondale and Ferraro addressed 711 members of the Black Delegate Caucus to secure the support of 400 of them pledged to Mondale. "I come to you today, because I've paid my dues,” he told them.

Then Jackson asked the delegates to stand in solidarity with him and show the party their communities should not be taken for granted in the general election.

Mondale had appeased Hart by accepting his peace plank, agreeing to help him retire his $4.5 million campaign debt, and granting him a prime time speaking slot prior to the presidential nominations. Hart would finally concede.

On Wednesday night Nebraska Governor Bob Kerrey introduced Hart, who received a 15-minute standing ovation.

“Our nation needs new leadership, new direction and new hope," Hart began, reiterating his campaign theme and setting his marker for 1988. “Our party and our country will continue to hear from us. This is one Hart you will not leave in San Francisco.”

Hart credits that line to Frank Mankiewicz, a former RFK press aide then advising him. Top JFK aide Ted Sorenson was advising Hart too. Hart noticed John Kennedy, Jr. was in the convention hall watching his speech.

“To the Republicans,” Hart said, “Take no comfort from this Democratic family tussle. Ronald Reagan has provided all the unity we need. Not one of us is going to sit this campaign out. You have made the stakes too high.”

As he did in the primaries, Hart touted modernizing the U.S. manufacturing base, retraining workers, and investing more in infrastructure and technology.

“The times change, and we must change with them. For the worst sin in political affairs is not to be mistaken, but to be irrelevant,” Hart said.

Invoking a JFK metaphor, he spoke of the “torch of idealism” being “passed to yet another generation,” his generation, the children of the 1960s.

Hart concluded, “If not now, someday we must prevail. If not now, someday we will prevail.”

Late Wednesday came the roll call of the states -- 3,933 delegates voting for their party’s presidential nominee. There was no significant black delegate defection from Mondale.

The first ballot ended at 10:10pm -- 1:10am on the East Coast -- when New Jersey, the state that saved Mondale’s campaign with his primary win there June 5, cast 115 delegates for Mondale. The final tally was: 2,191 delegates, or 56 percent, for Mondale; 1,201, or 31 percent, for Hart; and 466, or 12 percent, for Jackson.

Hart rushed back to the podium to call for the nomination by acclamation. “There is a time to fight,” he said, “And a time to unite.”

Jackson followed Hart to the podium. “Our convention has made a decision,” Jackson said. “There is a time to compete, a time to challenge, a time to cooperate.”

###

Ferraro was in the bathtub trying to relax. The vice presidential roll call was about to begin on the final night of the convention, Thursday, July 19. Her family was watching the proceedings on TV in the main room of her suite. When her nomination got to Arkansas, the fourth state alphabetically, it yielded to New York, whose delegation proposed she be confirmed by acclamation. There was no opposition.

Ferraro jumped out of the tub into a white dress and sped to the Moscone Center in her motorcade. She took the stage to the strains of “New York, New York.” The first woman to be on a national ticket thought to herself, “Don’t trip.” She walked without incident, waving and smiling, to the podium and checked the teleprompter -- her first time using one. She said to herself, “Speak slowly.”

“My name is Geraldine Ferraro.” Loud cheers. “I stand before you to proclaim tonight, America is the place where dreams can come true for all of us.”

Ferraro saw a sea of women on the floor. Many had borrowed floor passes from male delegates for her speech -- activists who worked years for equal rights. Some brought their daughters or granddaughters. Some were holding flowers. Others waved American flags.

“I remember thinking I just don’t want to make a mistake,” Ferraro recalled in her interview for the 2014 documentary, "Ferraro: Paving the Way," directed by her elder daughter, Donna Zaccaro.

“I told my daughters whatever you do, don’t cry. Because we can’t. Women can’t cry,” Ferraro recalled.

Zaccaro said, “We did get emotional anyway. We didn’t always listen to my mother. We tried to.” She was watching from the side of the stage with her siblings and father.

When Ferraro said, “I proudly accept your nomination for Vice President of the United States,” there was a loud demonstration. “Gerry! Gerry! Gerry!”

“There are no doors we cannot unlock,” she said. “If we can do this, we can do anything.”

An Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution was still a goal. In the meantime, there was the issue of equal pay and the feminization of poverty.

“It isn’t right that a woman should get paid 59 cents on the dollar for the same work as a man,” Ferraro said. “You deserve a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.”

The platform Ferraro had shaped advocated fairer taxes for lower and middle-income families and protecting abortion rights for women.

“We will not have a Supreme Court that turns the clock back to the 19th century,” Ferraro said.

She did not shy away from foreign policy or criticizing President Reagan and his fervent anti-communism. “We want a president who tells us what we are fighting for, not just what we are fighting against,” Ferraro said.

Like Mondale, she called for a freeze in the nuclear arms buildup and action to defend human rights “from Chile to Afghanistan, from Poland to South Africa.”

She ended her speech with a promise of “a stronger, more just America.”

Her family took the stage as the orchestra reprised “New York, New York” and segued into “Those Were The Days,” the theme from "All in the Family." Ferraro took a curtain call. Of the five major convention speeches, hers would be the shortest, at 30 minutes, but perhaps the most important.

“We were so proud of her,” Zaccaro said. “She never thought it was just about her. She knew it was the symbolism.”

###

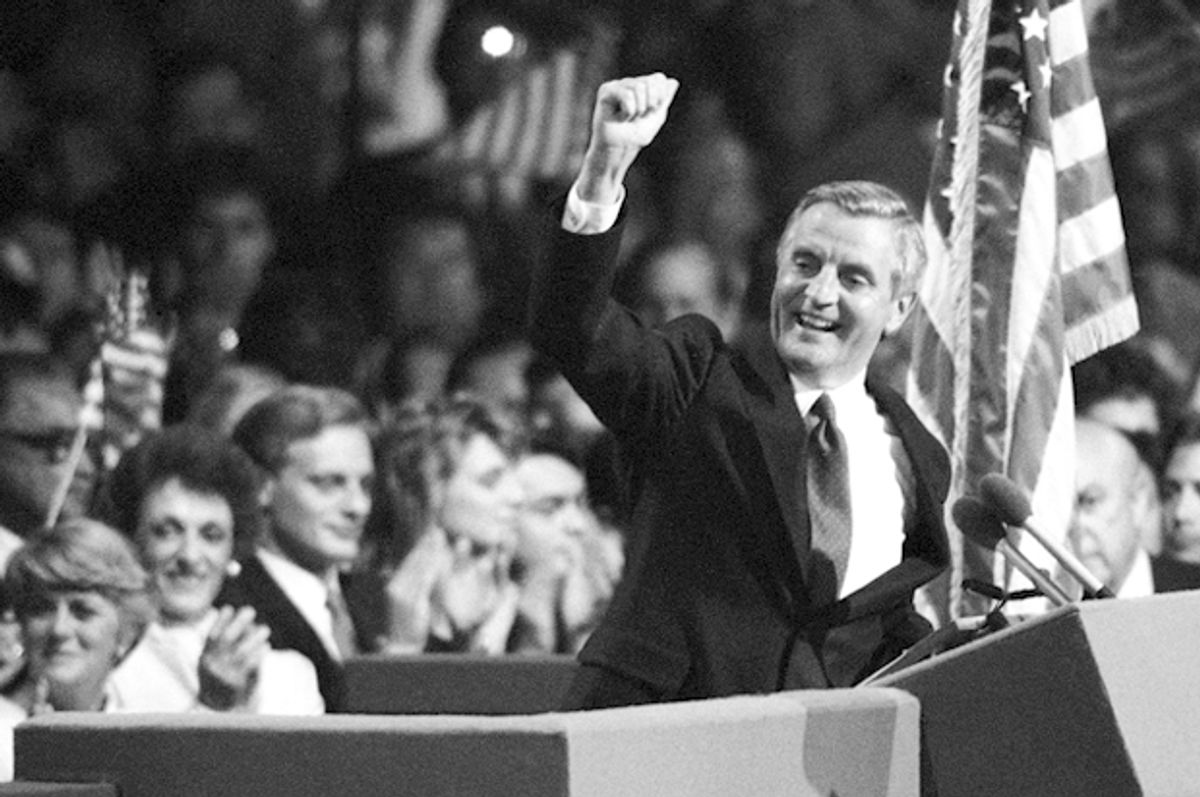

An hour later, Ted Kennedy introduced Mondale as the 1984 nominee. Effusively punching the air with his right fist, Kennedy said, “By his choice of Geraldine Ferraro, Walter Mondale has already done more for this country in one short day than Ronald Reagan has done in four long years!”

Kennedy left no aspect of the Reagan record untouched. Denouncing the president’s proposed anti-missile system in space, he said, “We must send him back to Hollywood, which is where Star Wars and Ronald Reagan really belong.”

Kennedy said his brother, Robert, who served in the Senate with Mondale, had seen “a very special promise” in him.

Kennedy concluded, “The dream we share will live again.”

Mondale walked onto the stage to the ultimate underdog anthem, the theme from "Rocky." As Mondale would depict the odds in his memoir, Reagan was selling morning in America, and he was selling a root canal.

If Reagan promised no new taxes, Mondale promised no new programs. He told his audience, “Look at our platform. There are no defense cuts that weaken our security; no business taxes that weaken our economy; no laundry lists that raid our treasury.”

The heart of his speech was its passage about fiscal austerity. “We are living on borrowed money and borrowed time. These deficits hike interest rates, clobber exports, stunt investment, kill jobs, undermine growth, cheat our kids, and shrink our future,” Mondale said.

“By the end of my first term, I will reduce the Reagan budget deficit by two-thirds,” Mondale continued. “Mr. Reagan will raise taxes, and so will I. He won't tell you. I just did.”

If picking Ferraro wasn’t a Hail Mary pass, then this statement was. Mondale believed he was showing leadership. He told me, “I think it was accurate. I think it was good economics. I think it was candor and honesty with the people. And it was the truth.”

Mondale became most passionate when criticizing the Reagan administration for not achieving a nuclear arms control agreement with the Soviet Union. “Why haven't they tried? Why can't they understand the cry of Americans and human beings for sense and sanity in control of these God-awful weapons? Why, why?” Mondale said. “For the sake of civilization we must negotiate a mutual, verifiable nuclear freeze before those weapons destroy us all.”

When Mondale finished his speech, the orchestra broke out into Kool and the Gang’s “Celebration.” His wife, Joan, came out, then their three children, followed by Ferraro and her family. There was a lot of synchronized waving. Balloons dropped. Hart and Jackson appeared on stage all handshakes and smiles.

“We finally had it all together. I knew it was a successful convention. Our polling during it showed we were going up every night,” Mondale said. “There’s a lot of evidence that we broke the mold there, and I think we did.”

###

The celebration was short-lived. By mid-August, Mondale’s convention bounce in popularity wore away. His Ferraro pick was popular -- 62 percent approved -- but Mondale was not. Reagan maintained a 15 percent lead, 49 percent to 34 percent among decided voters, according to a New York Times/CBS News Poll. Incredibly, three-quarters of the public said they had watched the convention on television, with the speeches by Cuomo and Jackson held in the highest regard. No matter who won, most voters believed their taxes would go up to reduce the deficit.

The Republicans used their national convention in Dallas in late August to underscore Reagan’s sunny optimism. “The choices this year are not just between two different personalities or between two political parties,” the president said in his acceptance speech. “They are between two different visions of the future, two fundamentally different ways of governing -- their government of pessimism, fear, and limits… or ours of hope, confidence, and growth.”

The pendulum swung in Mondale’s direction only once, in October, when Reagan stumbled in the first of two televised debates. The oldest president in history, later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, gave a meandering closing statement about driving on the Pacific Coast Highway.

“I was worried about him,” Mondale said. “One of the reporters on the panel questioning us at the debate told us after, ‘You should have offered your time to the president so the president could finish his trip down the California coast and tell us what he was thinking.’ He couldn’t remember where he was.”

On Nov. 6, Reagan won 59 percent of the popular voter and carried 49 states -- every one except Mondale’s home state of Minnesota -- and Washington, D.C.

Reagan won every demographic group, except for blacks and Hispanics, together only 13 percent of the electorate. He won the women’s vote, but by four percent less than he won men. Dotty Lynch, a pollster who helped discern the “gender gap,” estimated Ferraro might have added two percent to Mondale’s vote total.

The scrutiny of Ferraro resulted in extensive questions about her family finances, especially her husband’s business deals and their tax records. It was politically damaging and sparked prosecutorial probes of her husband.

Ferraro had given up her House seat to be on ticket and never held elective office again. “The way that she conducted herself during that campaign, even though they lost, made a difference in terms of what this country thought was possible for women,” said Ferraro’s daughter, Donna Zaccaro. “She felt like she made a difference, and so she was grateful to have been a part of it -- the good, the bad, the ugly.”

In 1986, after two terms, Hart retired from the Senate and focused on traveling and meeting world leaders from Jordan’s King Hussein to the Soviet Union’s Mikhail Gorbachev. Hart said, “I thought I was going to be elected in 1988.”

Had he won, Hart told me, he would have invited Gorbachev to his inauguration as a gesture toward ending the Cold War. Instead, Hart’s 1988 campaign imploded amidst reports alleging extramarital activities, and he never won a primary.

“I don’t think I lost in ’84. I thought starting where I started from it was a huge success,” said Hart, now 78. “I like to believe, and others who studied it think, the ’84 campaign was a turning point in Democratic Party politics, if not American politics, and that I sort of broke a generational barrier and opened the door for a whole lot of other people of my generation. So I don’t think that’s losing.”

In 1986, the one million voters registered by the Jackson campaign affected the Senate balance of power. Black voters were a key to victory for Democrats who won in the South – Wyche Fowler in Georgia, Terry Sanford in North Carolina, John Breaux in Louisiana, Bob Graham in Florida, Richard Shelby in Alabama (before he switched parties) – and helped the party regain control of the chamber.

In 1988, Jackson ran for president again and outlasted Hart, Senator Joe Biden, of Delaware; Senator Al Gore, of Tennessee; Senator Paul Simon, of Illinois; and Congressman Richard Gephardt, of Missouri. Jackson won a dozen primaries or caucuses and finished second in the delegate count to the nominee, Michael Dukakis. His vote total doubled to nearly 7 million, and his white vote tripled. Jackson also registered another 2 million voters.

Jackson, now 73, said Barack Obama “inherited the coalition and the idea of that coalition. Much of the language that was used in 2008 was used in ’88.”

By 1988, television executives were in revolt over the diminished audiences for the conventions. The three major broadcast networks saw their 60 percent audience share during prime time convention coverage drop to 30 percent. ABC News President Roone Arledge called the Democratic National Convention boring and wanted to reduce hours further. Gavel-to-gavel coverage would become limited to CNN and C-Span.

In 1988 and 1992, many Democrats pined for Cuomo to run for president, but he never did. He served three terms as governor, and in 1994, Republican George Pataki defeated his bid for a fourth term. In a book length collection of his speeches, Cuomo said of his keynote address, “Not until eight years later, in 1992, it became clear we were right in San Francisco: the poor were getting poorer, the middle class was being battered, and the American Dream was vanishing except for a small but growing group of extremely successful people at the top of the economic ladder.”

But that message became a centerpiece of Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign. Cuomo made a nominating speech for him at Madison Square Garden.

In 1992 and 1998, Ferraro ran for the Democratic nomination for the New York Senate seat, but she failed to win the primary. In 1993, President Clinton appointed her as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Human Rights Commission and Mondale as U.S. Ambassador to Japan.

In 2002, Mondale filled in for Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone, when Wellstone died in a plane crash two weeks before the election. Mondale could not hold the seat.

Ferraro died from the blood cancer multiple myeloma in 2011. A decade earlier, she disclosed the illness and successfully lobbied Congress to allocate millions of dollars for medical research and public education about the disease.

Three decades after the high of the convention and the low of Election Day, Mondale, now 87, sees history rendering a kinder verdict on him than the voters did in 1984. The size of Reagan’s landslide relieved him of endless second-guessing. “I didn’t have to spend a lot of time wondering what I could have done to make up the difference,” he said. “I did my best, and I have no regrets.”

Shares