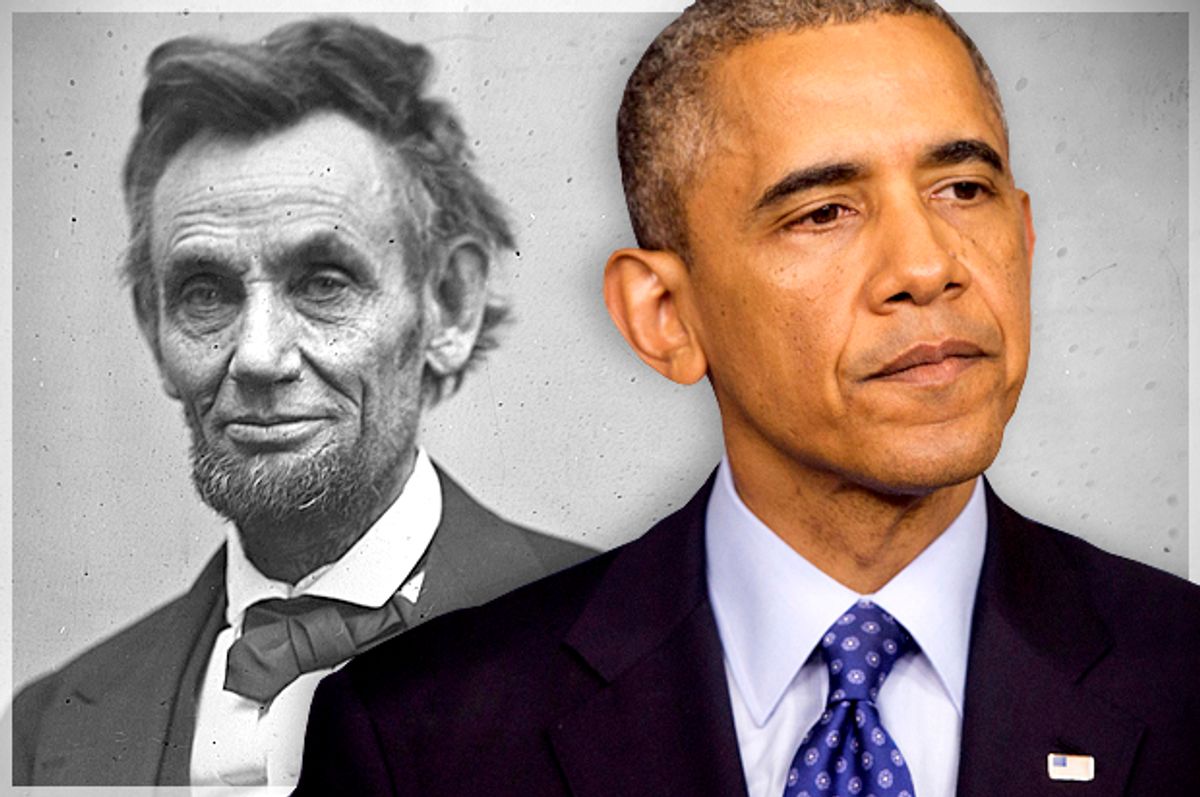

Earlier this month in a segment titled “Obama, Religion & the Islamic State,” MSNBC's Lawrence O'Donnell called Obama "the most gifted writer and speaker in the history of the American presidency."

“Oh, really?” I thought. “Does the name 'Abraham Lincoln' ring any bells?”

Given the title of the segment, Lincoln's Second Inaugural's particularly sprang to mind, with its deeply religious themes urging a firm course of action, even while freely admitting the impossibility of knowing God's will. It's a stunningly masterful speech that no politician in today's hypocrisy-drenched world would dare touch with a 10-foot pole.

And for all those right-wingers attacking Obama, and all those “moderates” who are troubled and confused, Lincoln's speech makes Obama's passing criticisms of religious violence and 'distortions' past seem tame by comparison. Lincoln's frank recognition of how deep and broad religious conflicts can go stands profoundly at odds with the self-comforting shibboleths which dominate any discussion of religion by politicians today. Before they say anything more, they'd be well advised to consider those words from a president who governed at a time of actual Civil War—a war driven in large part by conflicting religious visions, each reflecting different material interests as well.

Clearly, Lincoln's words would have also richly illustrated O'Donnell's most important point—the utter impossibility of identifying the “true” version of any religion, as Lincoln feely admitted that both sides in the Civil War were equally Christian in their own eyes: “Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other,” Lincoln even-handedly observed. He was not saying that anyone had “distorted” religion—and yet one side, if not both, must surely have been mistaken. One can only imagine what Fox News, the GOP presidential field, and our benighted pundit class would have said about that.

As O'Donnell's presentation unfolded, he used his claim of Obama's superiority to set up his criticism of Obama's speech at the National Prayer Breakfast as “the worst speech of his presidency,” because of his pandering treatment of religion, glibly dismissing all of its dark side as aberrational and false (a point Obama's knee-jerk rightwing detractors seem to have totally missed, as per usual). I had to admire O'Donnell's narrative craftiness, even as I remained surprised at his neglect of such an obvious master, who had articulated such a ringing presidential counter-example, fully recognizing religion's knottiest difficulties on the world historical stage, and making no excuses to avoid them.

Still, O'Donnell's narrative strategy was a bold move, particularly as the right went predictably and tiresomely nuts, basically because Obama's not a fundamentalist like them. Jonah Goldberg even defended the Crusades and the Inquisition, in order to excoriate Obama, who denounced ISIL as an example of “faith being twisted and distorted,” but also warned that Christianity had been similarly abused in the past, citing the pre-modern examples that Goldberg cheerfully defended, along with more recent Christian defenses of slavery and Jim Crow, which he pointed out, were “all too often was justified in the name of Christ.” Rather than being incendiary, Obama was being far too generous, as Ta-Nehisi Coates pointed out: “The 'all too often' could just as well be 'almost always.'”

But there's another level of irony here that should not pass unmentioned. You see, the Prayer Breakfast itself is a giant leap beyond even the normal realm of fundamentalist political religion, as noted by Jeff Sharlett, whose 2008 bestseller, "The Family: The Secret Fundamentalism at the Heart of American Power," was a deep dive into the belly of the beast of the organization behind the breakfast, and makes no bones about their authoritarian leanings, which even go so far as to include a certain reverence for Hitler. (The Family was founded in the 1930s.) “I've attended Nat Prayer Breakfast, briefly worked for organizers, & read 70 years of archive. Little in DC is more profoundly cynical,” Sharlett tweeted, also tweeting, “Annual defense contractor lobbying fest known as 'National Prayer Breakfast' culminates this morning,” and “Foreign delegations are often quite honest about why they attend Nat Prayer Breakfast: paying court to power, begging for guns.”

The vast gulf between the Family's elite, authoritarian fundamentalism, and the loving Christ that most Christians think of was captured by one reviewer of Sharlett's book, Frederick Clarkson, when he wrote:

Even barbaric military dictators are introduced to Jesus and invited to pray with a designated Family liaison, as in the case of Gen. Siad. They don’t really care about whether he is a Christian or ever becomes one; because it is all about power and power relationships of a kind that are greased by amoral rationalization and turning blind eyes to horrendous crimes —such as the Indonesian genocide on East Timor, which was conducted even as the Family developed relationships with General Suharto, and played an intermediary role with the U.S. Government.

So the very event at which Obama spoke was the embodiment of the contradictions he was touching on—not centuries or even decades in the past, but right there in the very air he was breathing even as he spoke. In the wider world, this buried reality of what the National Prayer Breakfast and the Family are actually about only serves to crank up the cognitive dissonance meter to a mind-numbing 11. With the Family's long history of guns for Jesus—with or without Jesus— as context, it's particularly bizarre to replay almost anything anyone has said about Obama's remarks; not that Obama's remarks themselves don't appear ludicrously misdirected in their focus on religions' historical “distortions,” the point that O'Donnell had homed in on.

Indeed, there is so much cognitive dissonance flooding the zone that a strategic retreat to contemplate Lincoln's Second Inaugural—a brief 700 words—seems far the wisest course of action for us, to get our bearings back. Lincoln is a frequent favorite fundamentalists like to cite when bashing modern politicians, especially presidents, for being insufficiently religious. But his actual views—infused with profound humility in the face of mortal limitations—could not possibly be more at odds with their confident, dictatorial, know-it-all triumphalism.

Just to be clear about the inaugural's religious bona fides [noted here] as well at it's direct confrontation with human limitations, and consequent contradictions, here is how it movingly concludes:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Think what Lincoln is saying and doing here. “With malice toward none, with charity for all,” he says openheartedly, “let us strive on to finish the work we are in,” by which he means finish the fighting of America's bloodiest, most terrible, most divisive war in its history. Yet, what might otherwise be a monstrous Orwellian act on Lincoln's part is nothing of the sort. The war at that point was virtually over. There was no doubt left as to its end. The desire to shift focus to peace and healing was not to avoid anything personally or politically damaging to Lincoln (just reelected, handily) or to his allies, but rather, to protect the nation's future. What's more, the contradiction involved is not denied or obfuscated—as can be seen quite clearly earlier in the body of Lincoln's brief, swift-moving speech, as we'll see shortly.

What kind of attitude does Lincoln invoke in approaching this task he lays out? It's the same sort of profound, openly admitted contradiction: “with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right.” [Emphasis added.] Notice what he's not saying. He's not saying “with firmness in the right as God's right hand,” as virtually every U.S. politician today would say—or at least silently imply. He's not claiming any sort of divine sanction for the task he calls the nation to. It is purely a matter of limited human understanding, to the extent that God has allowed it. And yet, Lincoln's call is unwavering.

There is tremendous moral authority in the close of this speech, and it's deeply imbued with religious sentiment. Yet, the moral authority is not a product of God's majesty. To the contrary, it's a product of recognizing human limitations, and the responsibilities we owe—to those past, to the future, to those who've sacrificed so much—which weigh all the more heavily because of our limitations, both of understanding and of power.

And that's just what Lincoln said in the last sentence of his speech! No wonder I thought of it when I did. As O'Donnell proceeded, and his guests joined him in a fascinating discussion, I could not help but think over and over again of how much richer the conversation would be, if Lincoln's words had played a role in shaping it. And the same is even more true for the wider waves of controversy that have spread from Obama's remarks.

O'Donnell went on to make some very good points—as did his guests, Zainab Salbi, Asra Nomani and Jerry Coyne, in what was certainly an interesting segment, particularly regarding the question of what constitutes authentic faith, as opposed to its distortion or hijacking. “No one here is saying that ISIS is the real Islam, but once you say it's not the real Islam, you are then implying that you can identify there is a real one,” O'Donnell said, articulating his most fundamental point. And yet, he also contrasting Obama's “worst speech” with a supposedly much better one, at the U.N., "not speaking to religious leaders" where he "struck very different tone," O'Donnell said, approvingly. To wit: "It is time for the world, especially in Muslim communities, to explicitly, forcefully, and consistently reject the ideology of organizations like al Qaeda and ISIL.”

There we have the “good Obama” as O'Donnell would have it, effectively channeling Fox News and its Islamophobe “experts” like Pam Geller, completely ignoring the fact that Muslims have been doing exactly what he's demanding for a decade and a half now. These two statements by O'Donnell highlight how well he grasps the problem in the abstract, yet how poorly he has formulated it by limiting his frame of reference to one dominated by Obama.

As the segment progressed, Salbi and Nomani shared sharply differing, yet similarly nuanced views of Islam's current historical state, which don't fit so easily into the good religion/hijacked religion dichotomy Obama set up, but which do resonate with Christianity's troubled history that he referred to. If only America were not so muddled in its own illusions, the arguments Salbi and Nomani deployed could greatly enhance our understanding. But, simply put, we're just not up to that level yet. We need to deal with our own demons first.

In all, Coyne got off the best single line, riffing on the “hijacking” theme, when he said, “What's happened with Christianity is that it's become tamer over the centuries because it was hijacked by the Enlightenment values, the secular Enlightenment values that have gotten rid of all those horrible statements in the Old Testament.” It wasn't nearly as simple as that, of course, particularly given the moral progression within the Old Testament, from Deuteronomy and Leviticus to the last of the Hebrew prophets who so inspired Martin Luther King Jr. Still, there's more than a bit of truth in what Coyne said. After all, it was the defenders of slavery in the generation before the Civil War who had both Old and New Testament scripture on their side, and fully employed it, as Larry Tise documented in "Proslavery: A History of the Defense of Slavery in America, 1701-1840." And yet, Lincoln still spoke as a deeply religious man, taking a profoundly different view of what his religion taught him, believing as he did in a living God, not one bound by textual literalism. And so we turn back to consider the body of that speech and what it has to teach us.

First, consider how Lincoln framed the debate, bending over backward to be fair to those who made war against him, and yet at the same time clearly holding them accountable as the ones who would make war, as opposed to accepting it:

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it, all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war—seeking to dissolve the Union and divide effects by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war, but one of them would make war rather than let the nation survive, and the other would accept war rather than let it perish, and the war came.

One hundred and fifty years later, Southern whites as a whole still cannot muster this measure of honesty. They still cling to locutions like “the war of Northern [or Yankee] aggression,” even though South Carolina began the war of aggression by attacking Fort Sumter. And yet, Lincoln simply lays out the facts, he does not dwell on the South's terrible responsibility for national near-destruction.

Lincoln then moves on immediately to another truth that Southern whites as a whole (and many others) still deny—that slavery lay at the root of the war. And yet, he expresses it in a way that respects the confusion generated around it (“somehow the cause of the war”) while quickly adding the particulars (“To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest”) that cut through that same confusion:

One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was somehow the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union even by war, while the Government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.

That passage alone is a historically brilliant piece of narrative craftsmanship, but it's only the setup for what's to come. First a set of common constructions, treating both sides as equally mistaken about the war:

Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with or even before the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding.

And one more set of common constructions, in much deeper, more profound moral register:

Both read the same Bible and pray to the same God, and each invokes His aid against the other.

Leading immediately to a partial splitting, in which Lincoln clearly reveals which side seems strange (other) to him, and yet, partially preserving the previous parallel spirit, also warns against getting carried away, and presuming a position that belongs to God:

It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God's assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men's faces, but let us judge not, that we be not judged.

He then returns to the compact presentation of both sides in equal terms, but only as a stepping stone to finally start reflecting on—though not claiming to know—God's will:

The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes. "Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh."

And then he contemplates what this may mean—a vision of man's fate with clear Old Testament echoes:

If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him?

Then again, ever-so-briefly, Lincoln momentarily returns to the human perspective, expressing a nation's hope as presidents often do, but more urgently, with more anguish than any other ever has:

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.

And suddenly snaps back again, to contemplating the terrible price that divine justice might well require:

Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said "the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether."

This concludes the main body of the speech, followed only by the concluding sentence I discussed above. Whether one agrees with Lincoln or not in any or all of his particulars, one cannot deny his moral seriousness, or the authenticity of his religious faith. Nor can one find any trace of the hypocritical self-justification that political religious talk in our own time is utterly riddled with. Lincoln is clearly less certain that his side is right than the likes of Harriet Beecher Stowe and the abolitionist forces she helped rouse, without which emancipation would never have come. And yet, he has ultimately sided with them, when it could no longer be avoided, and having taken that stand, he remains firm in it, even while still allowing his limited knowledge, and lingering uncertainty.

Lincoln's uncertainty is not that of a secularist lacking in a religious framework of right and wrong. It is, rather, the uncertainty of a man of faith, who recognizes he is not God, and cannot claim God's certainty as his own, lest he be guilty of trying to usurp God's place. The state of divine unknowing is a frequent topic of mystics, but here it becomes the subject of a secular (though religious) political leader, the ultimate pragmatic man of the world, reflecting not on the fate his own soul, but of his entire country. Although it is a very different sort of uncertainty in its origins, it is, nonetheless, uncertainty, directly opposed to the certainty of fundamentalists and all fanatics.

Learning to live with uncertainty is learning to be human—whether we be religious or not. That is the link, the anchor on the oceans of uncertainty that Lincoln still provides us, 150 years later. We would all do well to reflect deeply on this, and know there is good reason why it's Lincoln, not Obama, who remains not just "the most gifted writer and speaker in the history of the American presidency," but also the most relevant in thinking through what must be done, knowing full well that, at some level, we must act, though we do not know everything for certain. And never will.

Shares