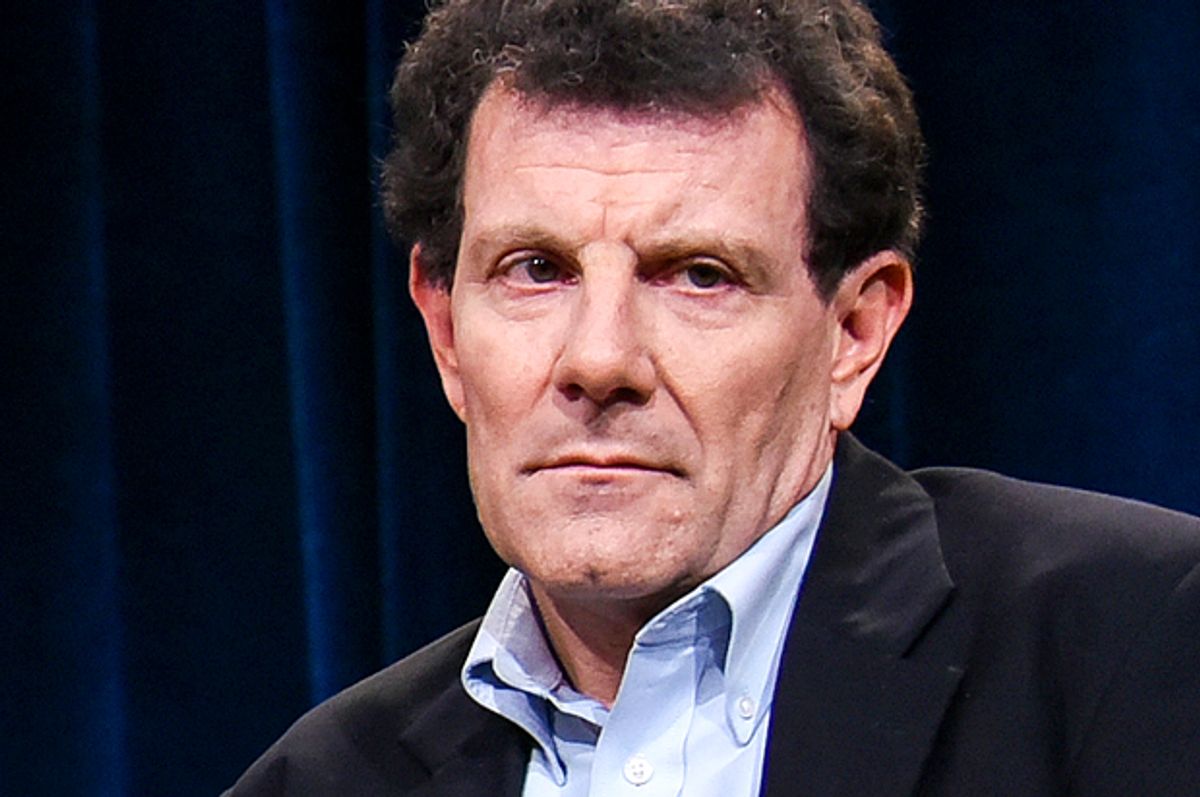

Broad generalizations about humans can be tricky, because we are strange and specific creatures. Nevertheless, I think I’m on pretty solid ground in saying that, by and large, people like to be right. Not right in a “get right with God” kind of way, but right in the way that Wolf Blitzer, when he was a guest on “Jeopardy,” was nearly always not. But while the sensation of wrongness is typically unpleasant, there are rare circumstances when vindication can almost feel worse. And in all honesty, I must confess that reading the latest Nicholas Kristof column in the New York Times was, for me, one of those moments.

For those who haven’t read it already: Kristof’s piece is a mea culpa, which is all too rare in punditry, and it’s a mea culpa in defense of unions, which is rarer still. To be fair, Kristof was never known to be an especially passionate or dedicated foe of unions; it’s not as if this is Glenn Greenwald penning an ode to the NSA. But in earlier times, Kristof, like most bourgeois and cosmopolitan elites, held a view of unions that fell along a continuum. On one end of the continuum, unions were seen as a necessary evil; and on the other end, they were considered to number among progress’s many enemies. But now, apparently, Kristof has reconsidered.

Before stating, with admirable directness, that he was “wrong,” Kristof describes his previous view of unions as one of “disdain.” When the Kristof of yesteryear thought of unions, he writes, he envisioned them as selfish, lumbering entities that were in the habit of “bringing corruption, nepotism and rigid work rules to the labor market.” And although Kristof did not himself own a business, he worried that a tight labor market would end up “impeding the economic growth that ultimately makes a country strong.” As anyone who's read Matt Yglesias, the Economist or Tyler Cowen knows already, this is neoliberalism 101.

But that was then and this is now; so what’s happened to change Kristof’s mind? Concerning that question, the much-lauded journalist’s prior clarity begins to slip. “The abuses [of unions] are real,” he writes. “But, as unions wane,” he continues, “it’s also increasingly clear that they were doing a lot of good in sustaining middle class life — especially the private-sector unions that are now dwindling.” This is true enough, but it’s also not quite the revelation I’d expected. The parallel decline of America’s unions and its middle class has become so well established that it’s almost banal.

As if to prove my point, Kristof then goes on to cite a good number of respected studies from prestigious academics that all show the connection between unions’ health and the middle class’s vitality to be strong. But while it’s always good to have the Ivy League on your side in a world run by Ivy Leaguers, the fine people at the American Sociological Review were hardly the first people to note this connection. Even if we want to discount the obviously biased perspectives of the unions themselves, fighting for and believing in the positive good of organized labor was, for quite a while, a bedrock principle of American liberalism and the Democratic Party.

In other words, this is a lesson Kristof should have already learned. And if he’s only changed his mind because the data has become overwhelming, that’s not as much a shift in thinking as Kristof seems to believe. The financial crisis and the Great Recession were terrible for both unions and the middle class, no doubt; but the NAFTA and WTO ‘90s, as well as the Reaganite ‘80s, and even the Carter late-‘70s weren’t very good either! Granted, trends are always subject to change, but I’m puzzled as to why Kristof didn’t find Year 20 of American organized labor’s long, slow death to be troubling but considers Year 30 cause for a dramatic reevaluation.

Again: I understand that my complaints may sound petty, ideological or unforgiving. I get that by its very nature, a mea culpa requires someone to have been wrong about something others were not. My charge isn’t that Kristof was wrong before and therefore must be wrong now, too. Instead, what I’m really wondering is whether his about-face has involved a kind of change that goes deeper than adjusting to new data. Does Kristof now understand that unions are important for reasons that can’t be measured on a spreadsheet? Or will he change his mind once again in the unlikely circumstance that wages begin to rise more or less on their own?

So, yes, Nicholas Kristof’s self-flagellation and willingness to change his mind should be celebrated. Likewise, his embrace of unions, however reluctant (“I’m as appalled as anyone by silly work rules…”), should be applauded. But let’s keep the applause at golf clap levels, if we could. And I’ll hope that my next rush of vindication doesn’t feel so hollow.

Shares