In 2012, readers around the world were intrigued to learn that a researcher in northern Bavaria had discovered hundreds of never-published fairy- and folktales collected by the 19th-century folklorist Franz Xaver von Schönwerth. Working just a few decades after the Brothers Grimm, Schönwerth considered scholars his natural audience, and as a result the tales he recorded are bawdier, racier and significantly more scatological than the collection the Grimms published under the title "Children's and Household Tales." Everyone knows that the Grimms' fairy tales are much darker than the cleaned-up Disney versions, but with Schönwerth's, the action gets even more down-to-earth.

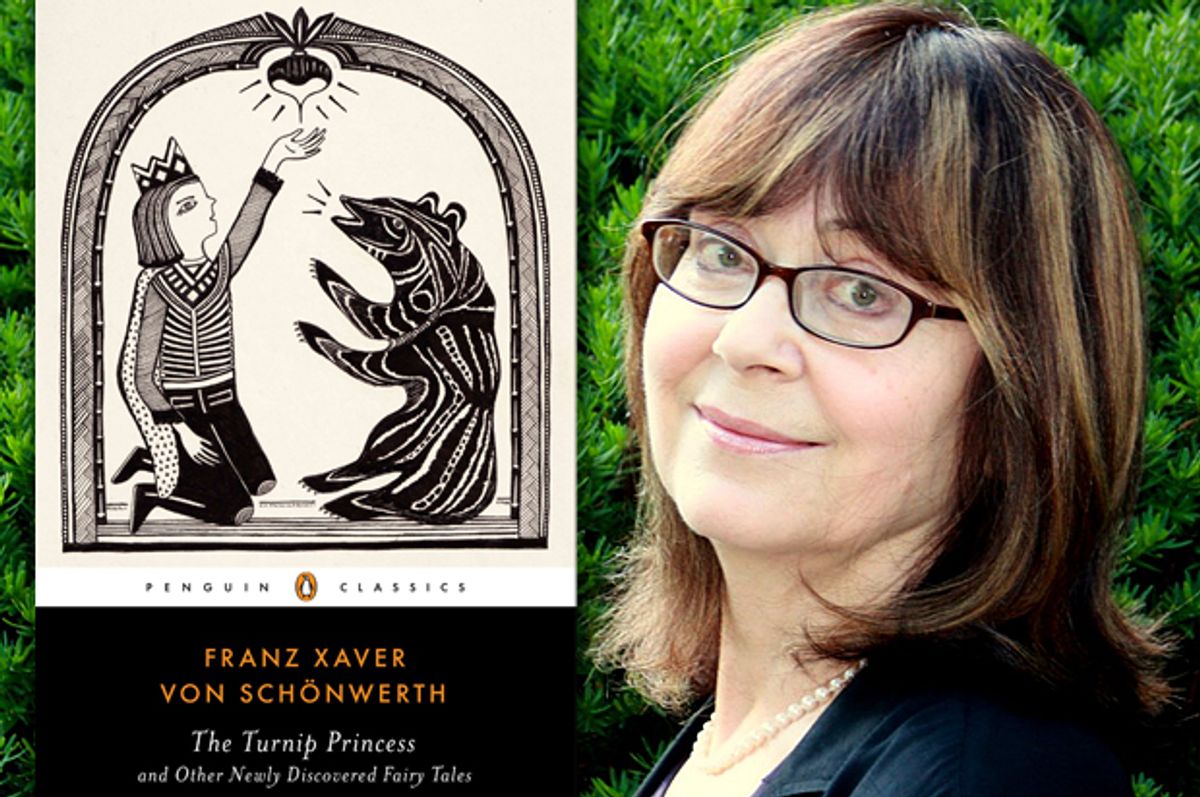

Erika Eichenseer, who ferreted Schönwerth's finds out of the Regensburg Archives, has been publishing single and collected tales in German over the past few years, but now at last there's an English translation of more than 70 of them, published this week by Penguin Books as "The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Fairy Tales." Maria Tatar, chair of the Program in Folklore and Mythology at Harvard University and distinguished editor of such books as "The Annotated Brothers Grimm," took on the tricky task of rendering 19th-century Bavarian folklore into modern English. I spoke with Tatar recently to find out more about treasures that await readers of "The Turnip Princess" and the surprising ways they upend our long-standing notions of the roles of heroes and heroines in some of Europe's oldest and most popular stories.

Can you tell me about how these manuscripts were found? Many people seem to think [folklorist] Erika Eichenseer just discovered a box with a trove of them in it, but that's not how it really happened, is it?

Erika unearthed hundreds of these stories in the [Municipal Archive of Regensburg] as a result of laborious archival research. She published some of them serially, or brought them to light, in Germany. A collection was published a few years ago in German. I included some of the stories in that collection in the Penguin edition. But there are also these additional stories that she's uncovered over the past few years.

What is their historical or scholarly significance?

To me they represent what my colleague, Alan Dundes, calls "folklore rather than fakelore." What we have here are stories that are less mediated than most of the more familiar fairy tales and folktales. There's a primary process of storytelling going on. They're less heavily edited and they're uncensored. The Grimms took great liberties with the stories they collected. The genius of the Grimms was to create this compact, standardized form of the fairy tale. They almost invented the genre of tale that is part of an oral storytelling tradition but also in the literary culture. Schönwerth, on the other hand, was not interested in readership as much as in just capturing the tales as they were told to him.

One example in this book is a version of the well-known story of "The Valiant Little Tailor," the guy who kills seven flies with one blow. The Grimms' version has the flies hovering over a sandwich that the fellow has made. In Schönwerth, the flies are hovering over a dung heap. So that gives you a sense of the raw energy of the stories and the way that Schönwerth decided he was going to tell it straight up, tell it like it was.

Can you tell me a little bit about his sources? I know that, with the Grimms, some of the sources were what we might think of as more folksy. I don't know if "peasants" is the right word, but servants…

... or farmers. The Grimms were wonderful in just exploiting every possible resource. In some cases it was a friend who told the story to them. They also sent letters to colleagues and asked them to try to write up some of the stories they'd heard. They did hear what they called "the voice of the people" -- meaning, the peasants, farmers, workers, tailors. So in some cases they were able to get working-class sources. They also looked at literary documents. So they plundered everything that they could find, to their credit, I think.

Schönwerth was more modest in his approach, although he didn't tell us a lot about his specific sources. He doesn't typically name or describe them, but we do get an occasional name, and we know that he was deeply invested in the idea of going to the common people, the common man or woman, and reporting the story as it was told. Sometimes he would even bribe people, giving them ... not necessarily cash, but some provisions or something like that. Then, of course, you think that means that the teller could have modified the tale for him, trying to make it as pleasing as possible. There's always a certain amount of distortion when you move from the oral to print culture.

If I remember correctly, a lot of the tales the Grimms collected were stories that middle-class people remembered hearing from their nursemaids or other servants as children. So those stories were mediated and possibly distorted by that route as well.

That's true. Schönwerth was doing this a little later than the Grimms. The Grimms were actually quite young when they collected, so their two volumes appeared in 1812 and 1815. Schönwerth did most of his collecting in the 1850s. The Grimms were aware of him and admired him. But they knew Schönwerth was doing something completely different, that his project was not the same as theirs.

Because his approach was more anthropological, as opposed to a popularization? I'm not totally getting the distinction here. You mean that he's interested in recording these as accurately as possible, not in creating a bestselling book, like theirs?

Or a standardized form for the fairy tale itself. I think you have it exactly right, that is, it's more of an anthropological, folkloristic model. Schönwerth just refuses to homogenize the stories, and so you find that there's a lot more gender bending in Schönwerth. There isn't that strict division of gendered labor that you find in the Grimms. The Grimms don't have a male Snow White, for example, whereas Schönwerth does. Schönwerth has a male Cinderella. He has a boy who wears out iron shoes while searching for the woman he loves, a figure who is a girl in "East of the Sun, West of the Moon." He has a prince who gets under the bedcovers with a frog so she can be turned into a beautiful princess. You just don't find that in the Grimms at all.

There's also something very much of the 19th century bourgeois in the idea that we need to divide up the kinds of things that heroines do from what heroes do. It's the job of the female characters to learn to love the toad and for the male it's his quest to slay a dragon.

Exactly. Where else but in Schönwerth do you find a boy who works in the kitchen? He acts like a Cinderella. You never find boys in the kitchen cooking in the Brothers Grimm.

What was it about the first half of the 19th century that made people so keen on this kind of tale-gathering project?

First of all, there's a very clear recognition that the stories are disappearing. The culture that produced them is about to, not disappear, but to fade away. It's quite early. We're not yet in the period of the Industrial Revolution. But there is a sense that there's less leisure time. There's the rise of the city, and urbanization. Nostalgia about the past and a desire to preserve a cultural heritage before it disappears. This is also the time when people are learning how to read. They're buying books. The whole rise of the bourgeoisie and the idea of having a library. The Grimms, for example, when they first started publishing their scholarly books, they would sell 15 copies or so. Then, suddenly, with "Children's and Household Tales," they had a bestseller on their hands. Which was in part why they started editing and taking out the vulgar and (for us) the sexy parts of the stories.

The tales as the Grimms told them also developed a kind of disciplinary edge. They called their volume "a manual for manners." They were transmitting a cultural heritage and also teaching proper behavior.

We should be clear that there was a progress toward that role in the Grimms' editions of their tales. First, there was an original, scholarly collection that was, shall we say, more rough-edged. But as the collection came to be seen as a childhood or household classic, they cleaned it up and introduced more morals.

More morals, and oddly more violence, to give them a kind of emotional ferocity and that disciplinary edge. My favorite example of this is the story of Hans the Stupid. He's a kind of everyman, who can make girls pregnant by looking at them. The Grimms got rid of that very quickly! It was not a shining example of good behavior. It was not part of a heritage that they wanted to pass on to children.

I was struck by several themes that came up repeatedly in these tales. There are a few stories where parents turn against their son because he's too strong. It doesn't seem that different from the more familiar stories where the stepmother takes against the daughter who's prettier than her. We're always hearing about the wicked stepmother and how she hates Snow White for being the fairest of all. That is a real generational rivalry, but the same rivalry happens between fathers and sons, except it's about virility or strength instead of beauty. I was fascinated to see that there is a male equivalent of the beauty rivalry.

It's remarkable, in one particular story, how the parents team up against the son. You would think they would make his strength work for them. Instead, they try to do him in! That's another great difference between Schönwerth and the Grimms. For the Grimms, it is always the evil stepmother. The fathers tend to be exonerated. Sometimes they just go along with the stepmother, and they're not described as complicit in any way, just overpowered by this demonic wife. Whereas in Schönwerth, there's the story of Prince Goldilocks, where the father sends the boy into the wilderness and wants to kill him. That is unheard of in the Grimms' tales.

You point out that we have this one-sided view of the way gender works in fairy tales partly because of how the Grimms edited their collection, but don't you also feel that partly it's because over time, as the oral storytellers became overwhelmingly female, they also might have focused on female characters more?

I'm not so sure. The Grimms picked and chose their stories, and I think that they just had some sort of deep reverence for fathers. Fathers could do no wrong for them. For example, take the story of Cinderella, where the villain is the evil stepmother. But there's another version of Cinderella that circulated in the 19th century that is called "Donkeyskin" or "Thousandfurs," and in that one it's a father who loves his daughter too much. When his wife dies, he wants to replace her with his daughter. So you have a father who is totally out of control. Then he disappears in the course of the 19th century. I guess you're right, I shouldn't put it all on the Grimms. It could be part of a general trend toward focusing on evil women.

Reading this collection made me realize the degree to which intergenerational conflict in fairy tales is not just about the female characters but is a really pervasive theme. It's about the child's awareness that as much as their parents might love them, parents also know that their children will supplant them. Children can be threatening in this weird way, as well as being very much desired at times. The parents will fade as the children come into strength, and so the children also represent the parents' own deaths. So there's this ambivalence to the relationship. I didn't really see that before because it had always been presented in such a gendered way in the more familiar fairy tales, presented as a conflict between women about desirability as opposed to something even more universal than that.

Fairy tales are about the hyper-dysfunctional family. Think of "Jack the Giant-Killer": The giant is a proxy for the father. There's always something terrible going on, these domestic dramas that are larger than life and twice as unnatural.

What do you in particular find so compelling about this form?

What I really love about fairy tales is that they get us talking about matters that are just so vital to us. I think about the story of Little Red Riding Hood and how originally it was about the predator-prey relationship, and then it becomes a story about innocence and seduction for us. We use that story again and again to work out these very tough issues that we have to face. My hope is that this volume will get people talking about not just the stories and the plot but the underlying issues.

Milan Kundera has this quote in "The Unbearable Lightness of Being" about painting that goes something like: Painting is an intelligible lie on the surface, but underneath is the unintelligible truth. Folktales are lies, they misrepresent things, and they seem so straightforward and so deceptively simple in a way. It's the unintelligible truth beneath that's so powerful, and that's why we keep talking about them. They're so complicated. We have a cultural compulsion about folklore. We keep retelling the stories because we can never get them right.

Maybe there isn't a right version.

You're right, there is no right way to tell them. We just keep making stabs at it.

Shares