In the space of less than a week, NBC News anchor Brian Williams went from debonair multimedia superstar to celebrity roadkill, an instant has-been and laughingstock whose career in the “news business” is presumably over. We've moved on, am I right? Do you even remember who I’m talking about? It’s exactly the kind of story that Brian Williams himself would have covered at great length, pulling a long face and intoning soberly in his sonorous baritone about the integrity of the news media, but not quite masking the hint of a Schadenfreude smile: Can you believe this guy?

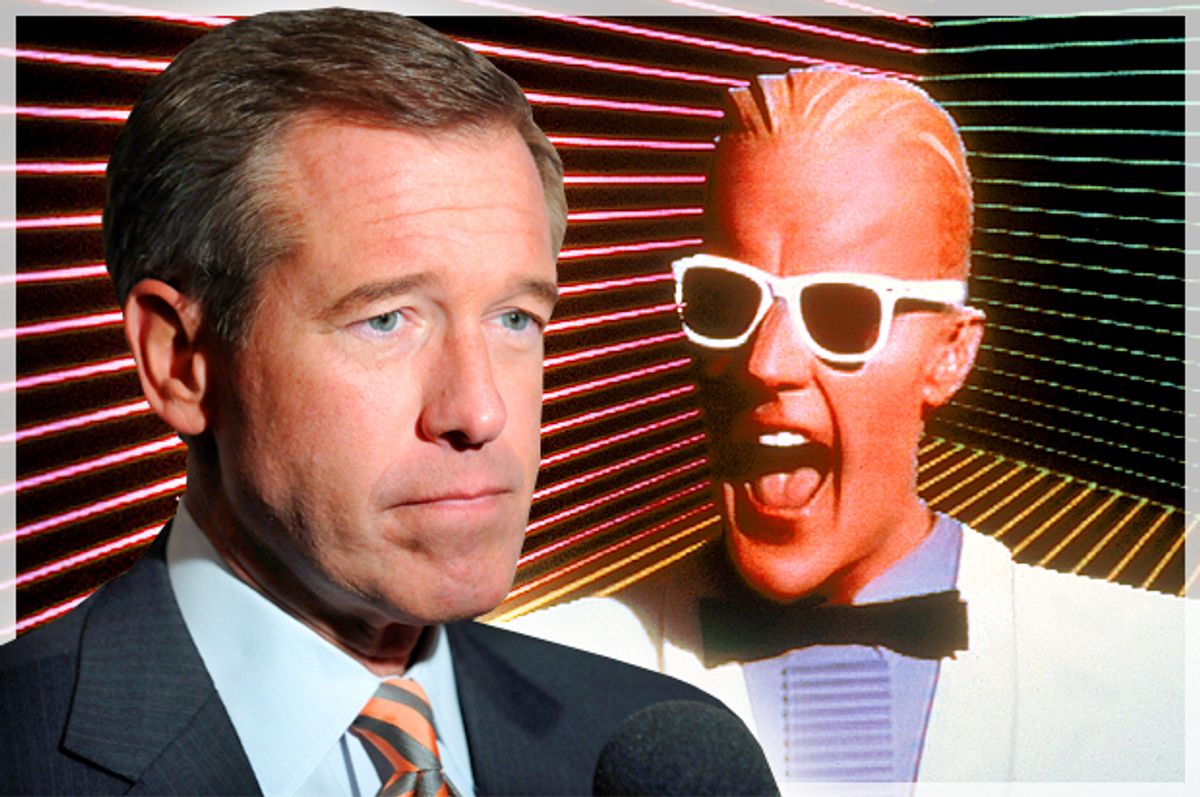

If Williams is to resurrect himself as a media icon, a lengthy course of ritual self-abasement will be required. While the celebrity comeback is always an appealing cultural narrative in American life, this is Brian Williams we’re talking about, and not someone actually interesting or important — like, say, Robert Downey Jr. Does anyone care enough about Williams to watch him don sackcloth and ashes and struggle to find his authentic self, with the help of Ellen or Dr. Oz? Authentic selfhood was never his brand, and neither was caring about anything. Williams represented the triumph of something else, an impervious, self-congratulatory cool as theorized long ago by media-studies pioneer Marshall McLuhan, and as embodied in the late ‘80s by the then-futuristic artificial intelligence Max Headroom.

What I’m getting at here is that while there’s a certain poetic justice in the downfall of Williams, his metamorphosing war stories are not really where the problem lies with him or his show or his network or TV news as a whole. As Jon Stewart amusingly diagnosed last week, Williams appears to suffer a low-grade case of “Infotainment Confusion Syndrome,” but the disorder evidenced by the massive media pile-on is far worse. It represents an impressive athletic feat of Freudian suppression or evasion, on a vast collective scale, for the media to treat the question of who rode in which Chinook helicopter on a particular day in 2003 as if it were some smoldering scandal, or represented tenacious self-policing. It’s a hell of a lot easier to confront Williams’ misstatements of fact — which have no practical consequences, except for him and his employer — than to think about the cascade of lies and cheerleading and propaganda and incurious circular groupthink that smoothed the way for America’s invasion of Iraq and characterized nearly all coverage of the war for years.

To insist that the Brian Williams story was news, in the face of all the other things the media declines to notice, requires accepting a perverted definition of what news means, and what function it is supposed to serve. The subject of this not-so-new kind of news is the surface of things, the smoothness and drinkability (as they used to say in Budweiser ads) of the media narrative itself, which has become the text, subtext and metatext of contemporary existence. To quote the 1960s Situationist Guy Debord, the “spectacle,” by which he means not just the mass media but the system of social relations constructed by mass media, “presents itself simultaneously as all of society, as part of society, and as instrument of unification.” (Debord’s epigrammatic 1967 treatise “Society of the Spectacle” can be read as a key to l’affaire Williams, and many other things besides.)

Nothing could be more newsworthy, in this universe, than the misdeeds of people who read the news. So we get news as the “gotcha” story, the gaffe story, the story about the celebrity who makes an ill-considered drunken tweet or tells an offensive joke near an open microphone. It’s no good mythologizing the past, which was full of different kinds of bad things, but can you imagine Brian Williams, or any other blanched and manicured TV news presence, confronting Joe McCarthy the way Edward R. Murrow once did? (Actually, let’s be fair: Katie Couric, endlessly pilloried for being too girly and lifestyle-oriented to read the news, would totally do that. Which is kind of why she didn’t last long in the anchor chair.)

There have been previous news anchors who attained celebrity, but Williams was the fulfillment of the anchor-as-celebrity, a difficult balancing act. We want famous people to have “real” personalities in private, or at least simulated real personalities, but we also demand a harmonious performance matched to their public persona. As my Salon colleague Sonia Saraiya explored last week, NBC tirelessly shaped Williams into an all-purpose brand identity that blended gravitas with coolth, like a delicious summer cocktail at the East Hampton yacht club. He could deliver straight news, such as it is, to the senior set and wry self-parody to the Jimmy Fallon audience and the YouTube generation. It was an inherently unstable or contradictory combination that required fine adjustments in Williams’ on-air persona and an unimpeachable performance as the character of himself. He violated the terms of that contract, and has paid the price.

I felt a moment of tenderness toward Williams for his increasingly exciting tales of helicopter peril, because it made him seem, albeit momentarily, like a real person. OK, it made him seem like a specific variety of real person: an insecure, blustery guy who was reaching for an authenticity or legitimacy he wasn’t sure he possessed. (I too have caught small sunfish that later became large and delicious trout.) It’s a highly recognizable human failing, which was a large part of the problem. The one thing someone in Williams’ position cannot do is display vulnerability, and that was the fatal flaw on which his media colleagues pounced.

Williams’ ideological function, if we view it through the extreme long lens of cultural history, was to make the delivery of news as a succession of disposable McMemeNuggets that alternately alarm or delight us and carry no sense of past or future – Muslims, Ebola, blizzard, “American Sniper,” Kardashian, repeat – seem both natural and inevitable. “The spectacle presents itself as something enormously positive, indisputable and inaccessible,” writes Debord. It is “the existing order’s uninterrupted discourse about itself, its laudatory monologue.” The revelation that Williams is just some dude given to spinning tall tales, so insignificant in itself, hints at the further and deeper revelation that the news business itself is a human concoction shaped by a particular ideological context and a specific understanding of reality.

In trying to decode the hidden meanings of the Brian Williams story, beyond its most obvious bait-and-switch qualities, I find myself drawn back to the late cultural critic Lionel Trilling, and the dichotomy or dialectic he observed in the early 1970s between “sincerity” and “authenticity.” (Trilling and Debord would have agreed about almost nothing, but they were dissecting the same cultural phenomena.) I can’t possibly do justice to Trilling here, but the tl;dr version might be that sincerity is about meaning what you say and saying what you mean, especially as a means of furthering public discourse and social cohesion, whereas authenticity involves accessing and expressing your true innermost self, while declaring you don’t give a crap about social convention. (“Mad Men” can be read as documenting Don Draper’s journey from sincerity to authenticity.)

Trilling thought he was trying to rescue an ideal of civil society founded on sincerity, but that the radical politics and emerging postmodern literature of the time had dumped sincerity as a bourgeois relic of the button-down 1950s, to pursue a doomed Marxian-Freudian-existentialist quest for authenticity. He didn’t live long enough to see the mannered, pseudo-authentic performance of Ronald Reagan – an actor playing a cowboy playing the president – sweep away the awkward sincerity of Jimmy Carter. Nor did he see sincerity make its big comeback in the “post-ironic” writing of David Foster Wallace and Dave Eggers, or in the political persona of Barack Obama, who ascended from the discredited authenticity of George W. Bush and Bill Clinton.

In the news business, we’ve seen a related process of evolution. Anchors from the glory days of network news, like Murrow or Walter Cronkite or John Chancellor, presented themselves as staid, reliable and deeply sincere, in a way that looks embarrassingly gauche today. We were not supposed to know anything about their boring private lives, see them trailed into fancy restaurants by paparazzi, or watch them swapping risqué cracks with Johnny Carson. Trilling acknowledged that sincerity was always a performance intended for public consumption, but saw its purpose as serving the public good, and believed it was best executed when it expressed “a congruence between avowal and actual feeling.” Again, I don’t want to stumble into a nostalgic haze: Murrow and Cronkite were “instruments of unification” or social glue within a Cold War narrative of universal progress and growing affluence that was at best a half-truth. It wasn’t the decline of sincerity that led to Vietnam and Watergate and the Black Panthers and the rise of feminism and the LGBT movement, even if Trilling halfway seems to think so.

Even back then during the birth struggles of the Debordian spectacle, you could see the dynamic in action that would eventually produce the perfect synthetic fusion of depthless sincerity and depthless authenticity, the human Max Headroom of Brian Williams. As a kid I was always fascinated by David Brinkley, who was first an anchor and commentator on NBC and then spent many years as the host of an ABC Sunday morning show that pioneered the opinion-driven roundtable format that is now so ubiquitous. Brinkley played the role of the comic foil or country-fried truth-teller, set against bland, avuncular co-anchors like Chancellor or Chet Huntley. He never tried to lose his distinctive North Carolina accent, often veered off the script into pithy asides or one-liners, and sometimes appeared to have visited the bar shortly before airtime. I have no reason to doubt Brinkley’s sincerity, but it was his persona of ornery authenticity that made him a huge celebrity, at least by the standards of the time. (He supposedly had to quit covering Hubert Humphrey’s 1960 presidential campaign because voters were more interested in meeting him than Humphrey.)

Brinkley’s performance of authenticity staked out an important pole of celebrity-newsman territory, notably the premise that even though he was wearing a suit and sitting behind a desk in New York or Washington, he was gonna speak his mind like a guy settin’ on a cracker barrel down to the country store. (In retrospect, Brinkley’s TV persona is so close to the character played by Andy Griffith in “A Face in the Crowd” that I wonder which of them inspired the other.) Every time Chris Matthews insists on saying “Amurka,” and every time Williams has made the dubious claim that he’s a big NASCAR fan – yet another of his scurrilous lies! – consider it a tribute to the lingering Brinkley legacy. (Brinkley was probably a middle-of-the-road Democrat like nearly all newsmen of the time – he wasn’t gonna tell us and it wasn’t supposed to matter – but Bill O’Reilly, Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh are his descendants too.)

Brinkley was too curmudgeonly and independent-minded, not to mention too molded by the norms and conventions of a different news era, to be the ideal model. (Covering his last presidential election in 1996, Brinkley had his own news-making gaffe, saying into an open mike that Clinton’s re-election meant four more years of “pretty words and pretty music and a lot of goddamn nonsense.”) What was desired was not quite the guffaw-inducing, overly earnest sincerity of the Cronkite age, nor Brinkley's unpredictable and unmanageable authenticity, but a smoothed-out, imperturbable blend of the two. A little Bush, you might say, and a little Obama. Somewhat relatable, to borrow a neologism from TV drama, but not too much. Somewhat intelligent, but not too much. Somewhat droll and ironic and detached – another Brinkley ingredient – but just enough to remind us that the existing order’s laudatory monologue about itself is the real subject of the news, and the show never stops. (As Debord summarizes the central maxim of the spectacle, “That which appears is good, that which is good appears.”)

That combination is conventionally summed up in the word “credibility,” which has been repeatedly described as the essential quality Brian Williams has lost and probably cannot get back. But what do the professed media experts mean by that? Do they mean that regular people think that everything Williams tells them is true, and may not think that anymore because he embellished a war-zone anecdote from a dozen years ago (that was a little embellished from its very first telling)? Give me a break. What they mean is that Williams’ performance of credibility, his branded and managed blend of sincerity, authenticity and mild irony, has now been disrupted. The man behind the curtain was rendered briefly visible; the simulation has a bug, and must be reprogrammed or replaced.

Williams comes closer than any human newsman ever has to being Max Headroom, who also transcended his roots and became a pop-culture celebrity. (He was the pitchman for New Coke – after the return of original Coke! Talk about fail.) Still, we can’t overlook longtime ABC anchor Peter Jennings, an important transitional figure in TV news history who was both Brian Williams’ most obvious role model and a near-certain source of inspiration for Max Headroom. Jennings was almost certainly the first network news anchor to go behind the desk with little reporting experience (at age 26!), although in later years he became a well-respected foreign correspondent with considerable Middle East expertise. In his early years as ABC’s anchor, Jennings came off as disconcertingly avant-garde, a sharp-dressed Canadian with an unplaceable mid-Atlantic accent and the mannerisms of a sommelier who isn’t convinced you can afford anything on the menu.

Jennings’ unflappable performance of credibility grew on America; by the time of his death in 2005, the news business had changed so much that he was a beloved elder statesman, a link to the lost era of Murrow and Cronkite. Brian Williams is never going to be anybody’s elder statesman now, and we no longer require links to ludicrous bygone eras. He looked for quite a while like a successful update of the Jennings formula, replacing the Canuck detachment and the ostentatious seriousness with a mild American self-mockery and a naked yearning for stardom. Williams was Peter Jennings reinvented as a “Simpsons” character. He was paid millions of dollars to provide a genial performance of credibility, a pleasing but impermeable surface that repelled all critical thinking and could be interchangeably positioned, from the nightly news to “Saturday Night Live” to the late-night talk shows. Now that the Kevlar membrane has been punctured, his usefulness is at an end.

Max Headroom, who was a fictional computer-generated TV host first introduced on British TV in 1985 – and who was not really computer-generated, since that was not yet possible – was never meant to give a credible performance of credibility. We understood right away that he was a corporate sham, albeit an endearing one, whose role was to distract us from the Matrix-like horror of reality. Max both parodied a certain template of smug, Jennings-like Anglo-American talking head, as it then existed, and foresaw its final victory. In the universe of the Max Headroom shows and movies, his propaganda-spewing, faux-intimate, media-savvy and altogether Williams-like persona was engineered (using the memories of an old-school muckraking journalist, now deceased) by the rulers of a dystopian future society dominated by big corporations and media conglomerates. I suppose no further comment is necessary. Except that of course there are important differences between Max Headroom and Brian Williams. In one case, we knew that the performance of credibility was simulated; in the other, we simulated, for as long as we could, the belief that it was real.

Shares