When you know you are going to meet Marky Ramone in person, and you see him in the flesh, your instinct is to walk first across the street and protect him from oncoming Ubers or falling debris. He is rock’s spotted owl, or black rhino: the very last of a magnificent species (apologies to Richie and C.J.), an original, living, breathing Ramone, and even though he glows with health, and is clearly in great shape, your gut tells you he simply must not come to any harm on your watch. Joey Ramone died in 2001, Dee Dee overdosed in 2002, Johnny lost his battle with prostate cancer two years later and only last year, founding drummer Tommy passed away.

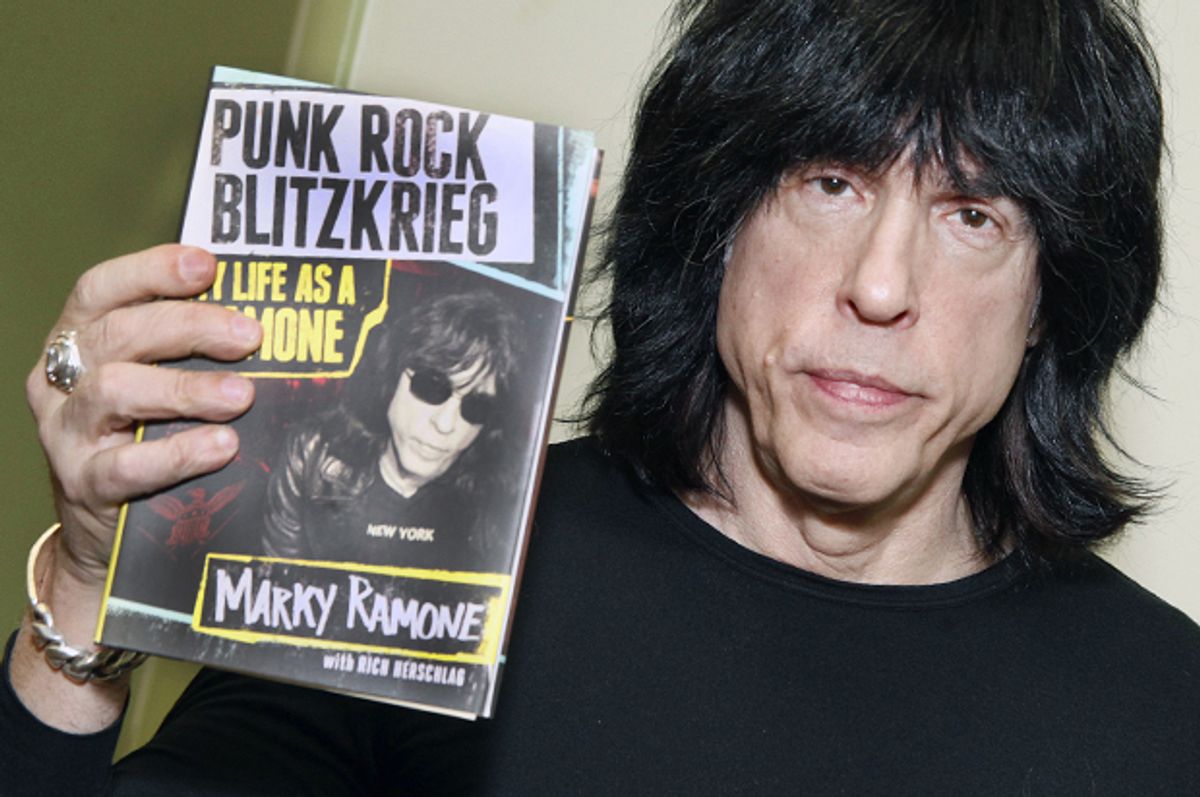

Marky, who joined in 1978 after Tommy decided to work behind the scenes, was regarded as one of the best drummers on the legendary CBGB’s scene on the Bowery, having played with cult rockers Dust, and both Wayne (now Jayne) County’s band (known, believe it or not, as the Backstreet Boys) and Richard Hell and the Voidoids. As a Ramone he appeared in the cult classic "Rock 'n' Roll High School," drummed for Phil Spector on the attendant album "End of the Century," bottomed out on booze, got sober, and rehired and saw the greatest New York City band to ever pound our pavement to their end in 1996. After a stint in the Misfits, today, he plays in Marky Ramone’s Blitzkrieg with party rocker Andrew W.K. on vocals. He hangs out with famous foodies like Daniel Boulud and Anthony Bourdain and has his own line of marinara sauce. And now, he’s written a memoir that holds absolutely nothing back and should be the last word on the Fab Five from Forest Hills (and Brooklyn). Titled "Punk Rock Blitzkrieg: My Life as a Ramone," it’s co-written with Richard Herschlag and was released late last month by Touchstone. (Note of full disclosure: At one point, long ago, my name might have been in the hat briefly as a co-writer; I cannot confirm that, but there was a discussion with my then agent, and I decided, correctly given how much I enjoyed the read, that it would be something that I would rather consume than help create.)

We met on an early February afternoon on a Bowery that looks nothing like it did back in the summer of ’77 (or even 2007). It was freezing and his jet black hair is covered with a wool watch cap. He wears a black mink coat (“I’m not a mink guy,” he explains, “but I swore I’d never freeze again.”). We head toward a high-end Italian place to have tea and (perhaps the only thing appropriate about the surroundings) pizza and talk at length about life in and out of the world-famous Ramones.

I was down here a couple of years ago with the four B-52's and they had not seen the area since they were still playing CB’s and they were shocked by the gentrification.

It’s more shocking when you’re not around to see it being built. When you’re away from it and then you see it, it’s shocking, like you said.

But you’ve taken the Bowery’s transformation in stride?

What do you do? Do you consider it progress? Debate it?

Philosophically, I think it’s just New York being New York. It changes. So let’s talk about the memoir, Marky. In preparation, did you read Patti Smith’s book? Did you read your one-time band mate Richard Hell’s book? Other books of the kind?

I read all the Ramones’ books and there was some interesting things in them, but I don’t like exaggerations, and I wanted to quell rumors. That’s one of the reasons why I wrote the book.

You’re citing Dee Dee’s book ("Lobotomy: Surviving the Ramones" with Veronica Kofman, published in 2000, two years before Dee Dee died of a drug overdose) or Johnny's book (2012’s posthumously published "Commando: The Autobiography of Johnny Ramone") or both?

All the books.

Even Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s classic "Please Kill Me"?

Yeah, you know the thing with Dee Dee is that he had a very vivid, childlike imagination. Anything you asked him, it was exaggerated. And obviously Legs went along with it, right?

And Dee Dee basically was a drug addict.

He had a scar and he would tell people that he was in Vietnam, but it was from his appendix.

Dee Dee didn’t really believe that he’d gone to Vietnam?

He didn’t but he tried to convince other people that he was.

So he was a button pusher?

That was a gift, considering the fact that he was such a great songwriter, that he can use all these [fantasies].

He was definitely a talented guy. But I also remember seeing him in the Chelsea Hotel years and years ago, in the late '80s, and he just looked so wasted. He just looked really unapproachably wasted, and it was sad because I’d been a Ramones fan since I was like an early teen.

And so I wanted to write my book. I figured 15 years, 1,700 shows, and it’s not just that. It’s the other bands I was in before the Ramones, like with Wayne County and Richard Hell and the Voidoids.

Both of them have written books. Wayne County wrote a book (as Jayne County, in 1996, one with the excellent title "Man Enough to Be a Woman"). Richard Hell wrote a book.

What did Richard write about?

I haven’t read his book. It came out shortly after Patti Smith’s and kind of looks the same. It seems like maybe the publisher was trying to make it like, if you enjoyed Patti Smith’s book then you should buy this book too. That’s kind of how it was marketed.

Just poetry?

No, it’s a memoir. It’s called "I Dreamed I Was a Very Clean Tramp." Back to your book, "Punk Rock Blitzkrieg." Had you kept diaries over the years? There’s a lot of vivid detail.

It’s basically in my head. The incidents that did happen -- how can you forget them? It was just so many things. We were such a unique bunch of people. We were out of the norm.

When you joined the Ramones after Tommy left the drum seat in 1978, it seems like you didn’t bargain for a life with such a deeply strange group of guys.

I thought they were all brothers. Friends. Everybody was getting along.

And yet there are these long descriptions of you in this cramped van with Dee Dee and he’s taking like nine baths a day. Joey is completely suffering from serious OCD and Johnny is just this general, barking out orders.

A drill sergeant that no one listened to.

It was basically insanity.

Tommy’d had enough because they were bullying him, and he wanted to produce. He wanted to be on the other side of the glass.

You write that when you came aboard for album four, "Road to Ruin," you wanted to kind of change their sound a little bit, if that’s fair to say? Kind of rock them up a little bit more?

I wanted to make it heavy. They needed it.

The later albums kind of are heavier and continued to be so through the '80s.

The three first albums are great, but there were enough of their three-chord wonder albums already. They needed to advance somehow.

So just to clarify, your recall is just sharp. It’s just a gift. You can remember the '70s, the '80s. You have no diaries? Did you have to look at mementos?

I had composition notebooks. The ones you went to school with. I also have the largest video library of the Ramones. There’s 400 tapes.

Of the backstage stuff?

Everything. That’s why I made the video “Raw.”

Did you contribute material to the Ramones’ “End of the Century” documentary also?

We had a separate producer and director for that. That was his take. I wanted to make a more fun movie about what is was like being in the band. The thing is, though, we were 90 percent fun and 10 percent, I would say, pent-up animosity. Especially between Johnny and Joey.

And you kind of skewed towards Joey, even though you say Dee Dee was your best friend in the band. I think, politically, you were more aligned with Joey.

Oh yeah. Definitely.

Johnny was a right-winged, hardcore conservative.

Borderline fanatical. The thing with John is he went to military school. It overlapped into the Ramones. But we didn’t listen to him.

But Marky, I have to say, when I’m reading your book, and I’m hearing these stories about Johnny carrying on, I literally had a couple moments where I was like, why didn’t you just punch him in the mouth?

I could’ve.

I mean, you can’t have a Ramones without Joey, but can you technically have a Ramones without Johhny? Is that why you held back? Because there’s an argument that anyone can copy that down-stroked guitar.

Not like that.

But the frontman is the frontman, you know?

At one point with Joey, he was canceling shows and we considered asking Stiv Bators from the Dead Boys to audition for the Ramones. This is just what happened, because Joey was doing separate things and the other two Ramones didn’t like it.

I just wonder, why didn’t you just tell Johnny to shut the fuck up?

I did.

I’m saying like permanently. Would that have been the end of the Ramones?

If I kicked the shit out of him, who would play guitar?

It’s bittersweet for fans like myself because you imagine the Ramones, and you want them to be like the Beatles in "Help!" You want them to all live in a house together. You want it to be like the Monkees or the Banana Splits where they fight crime together. You want it to be a family because you’ve all got the same last name! When you find out the truth that there’s such a volatile mixture of personality and chemistry, it is a little heartbreaking. I think a lot of fans exist in denial that that was the case and that you’re not and never were the cartoon Ramones, all for one. It’s like they say: never meet your heroes, yeah, or read their memoirs. (laughter) But everyone should read this because it’s funny and detailed.

It’s involved.

Yes.

It’s the beginning of my life. And it isn't just about the Ramones, again. It’s about Wayne County, and my times [hanging out] with the Clash and playing with Richard Hell and the Voidoids and touring England in 1977, all the way up to what happened backstage at the Hall of Fame induction [in 2002, their first year of eligibility].

Should we talk about the Hall of Fame speeches now? A lot of people were shocked that Tommy was the only one who thanked Joey --.

I did too!

Oh, sorry. I thought it was just Tommy.

No. I thanked Joey and his mother. And Joey’s siblings.

And Dee Dee thanked himself.

And John thanked George Bush, which had nothing to do with his career. Inappropriate.

I interviewed Johnny shortly before he passed away. It was one of his final interviews and it was for Spin. And I got the sense that even when he was facing the end, he had no regrets and was a hard guy to get to admit he was perhaps wrong about anything at all. I asked him about the Bush remark and he just said, “He’s the president.”

But what did that have to do with his career? Nothing.

I think he was trying to shake things up and show support for a war that was rapidly losing public support. In a way, it was the most punk rock thing he could do and in a way it was an asshole thing to do. It’s not the time or the place for it, at an awards ceremony, but he knew he had the audience. He knew he was sick too, maybe.

It was his last attempt. He wanted to get a rise out of the music industry. That’s why he did that.

You claimed you knew he was sick for a while. When you knew they were both sick, how did that emotionally resonate with you?

Horrible. First it was Joey.

Was the band still together?

No.

But you were still in contact with them and they were together as a business.

I noticed it in Joey’s physical appearance, especially on his skin. He contracted cancer. John didn’t yet have cancer until a couple years later. That’s probably one of the reasons why in ‘96 we decided to retire, because Joey’s chemotherapy had to start.

Towards the end of Joey’s life, you told Johnny that Joey was dying. By the way, why do you call him John and not Johnny in the book?

I guess it’s easier than Johnny. We used to call each other by our real names. I used to call Dee Dee “Douglas.” I used to call Joey “Jeff.”

So, anyway, you said to Johnny, “It’s the end. You gotta go see him.” You were in the room when Joey was on the way out.

I was the only Ramone to visit him.

That portrait you paint of Joey literally on his deathbed, God, I don’t think I’ve read any account about that.

Because nobody else was there!

Why do you think after all those years and all those records and all those hours on the road and the Ramones family nobody but you came? Dee Dee maybe has an excuse because he was probably strung out or in L.A. But you get on a plane. It’s 300 bucks. Jet Blue.

Pick up the phone and it’s even cheaper. He could’ve at least called him.

Do you think that would have meant a lot to Joey?

Yes. Definitely.

Did he look a lot different?

He clearly looked different. Thinner. Paler. The thing that John remarked was, Why should I go see the guy? I don’t like him.

That’s the one thing I just hit over and over again with Johnny when I talked to him on the phone for Spin. I was like, “You were brothers! You were Ramones. You at least have that bond." And he was like, "Yeah, if anyone else said anything about him, they would have a problem because he was a Ramone.” I guess to him it was more about the institution of the Ramones being bigger than the individuals.

Sounds cliché but it’s true. We left all that animosity off the stage.

So how does it feel for you now? You’ve had a rough year as far as losing some key people in that institution.

Yeah. Tommy. My father I lost. Arturo Vega.

Before that, the great guitarist Bob Quine (of the Voidoids). Linda Stein. Kim Fowley just died. Leee Black Childers. Hilly Kristal. Joe Strummer. I interviewed Leee a few times and he was a sweetheart. Is all this the kind of thing that compels you to tell your story by putting you face to face with your own mortality? You clearly live healthier now than some of the years you describe in the book.

Yes. I make sure of that.

You look great. I’m not sure of your exact age [note: Ramone is 62] but I have an idea and you look probably 10 years younger than you actually are. Playing the drums keeps you fit, huh?

It’s physical. It’s exercise. You can’t walk away from it.

But at the same time, time flies and we all have to reckon with mortality. Is that something that inspires you to write a memoir?

No. I don’t think about it. That had nothing to do with it. I just want to tell my real story. Being a Ramone. Being in this nucleus. Having my dealing with the other three Ramones and Tommy.

You tell details of your life that I think even serious Ramones fans don’t know: For instance, you write about your father being in show business too.

No, it was my grandfather, at the Copacabana and the 21 Club also.

Right. Your grandfather. And that you’re a twin. I didn’t realize that also. And your history as this kind of old-school Brooklyn-ite. I’m a fourth-generation Brooklynite also. I went to high school in Long Island because my parents got divorced. I grew up split between five towns and Canarsie, but I think my dad might have gone to the same high school as you? I have to double-check.

Erasmus? OK. Neil Diamond went there too. I was the Brooklyn guy who met the four guys from Queens.

I love how the book starts. You talk about how you get into rock 'n' roll through novelty songs, which nobody ever admits. They always try to credit cooler bands. You talked about “Purple People Eater” being the first record you ever bought.

And “Monster Mash.” I was a kid. I liked sci-fi and horror.

Did you have a rule, like no matter what, I’m going to be honest with this book? You’re very frank about your addiction and your recovery.

I wanted to put that in there.

Not to screw with your anonymity but I think the cat’s out of the bag. Did that help you? You can’t lie in those rooms.

There’s only lying to yourself and it’s a hindrance to your sobriety. But I thought it would be good to put in there because if anyone else has the same problem and they’re impressionable and they like what I wrote, maybe it could help them.

In that scene that was marked by booze and drugs and rock 'n' roll, you would just wake up and hit the bottle, right?

I would have wine in the morning.

It was a coping mechanism for you. And then you would have to drum and play these incredibly fast songs.

I never got high before I played. Not even during recording an album. Only one album.

Would Johnny be able to tell if you were fucked up?

Yeah. He would know. Some people who drink can drink and you don’t even know it.

But you didn’t drink a cocktail with an olive in it. You swilled from the bottle. You drank to get high.

I had my wine glass. They’d give you free drinks everywhere. I’d have my martinis. Rum and coke. And that would be it. But eventually, it was getting to me and I realized I didn’t like waking up with headaches anymore. It was affecting the situation with the other three Ramones.

What do you think about all the money the Ramones are making now from licensing and stuff like that?

I think it’s great. We live in a capitalistic society.

The Cadillac commercial that claims, “The Ramones started in a garage.”

It was a basement. That’s Cadillac. That’s what they thought.

Can we talk a bit about the Voidoids? Specifically Bob Quine? He might be my favorite guitar player. His stuff on those two Lou Reed records, “New York” and “The Blue Mask.” Also, the big Matthew Sweet record (“Girlfriend”) and obviously "Blank Generation." Nobody sounded like him and nobobody sounds like him today.

He came out of the box. Out of the cage. He really let loose with his Stratocaster. He knew how to play it properly.

Punk was so full of amateurs and genuine musicians. Can you tell when another musician is exceptionally unique?

Yeah. Definitely. Quine was one. Richard could have been one if he hadn’t succumbed to heroin.

When you met Phil Spector was he one too?

Yes. With Phil Spector, I knew immediately. He was on a different plane.

What about Joey?

Joey. I always considered him to be the perfect histrionic singer. Very timid, shy and introverted. But when he hit the stage, it was his. That spot that he stood on. Some people are like that. They transform.

You have bad karma in terms of being in bands with heroin addicts.

When you travel to other countries, the availability of getting the quality can definitely vary. Especially with Richard Hell. It made him very paranoid. What would he be able to cop and how good would the quality be? There would be a lot of hissy fits. Attitudes. But what I said in the book was if the heroin didn’t overcome him, he could’ve been the next Bob Dylan – a punk-poet on a much bigger level.

He had the words. He had the look. He had the voice and he had a great band behind it. Do you think he regrets it now?

Secretly, I think he does, yeah. He was the leader of the band. There were three other people with him. That was his responsibility. He didn’t take into account me, Bob, Thorn and Ivan, because of his love of heroin. So what was more important was his addiction, but it’s an addiction. Could he have helped it at the time if he wanted to? Yeah. But he didn’t want to. I guess he enjoyed it.

You write in typically great detail about auditioning for the Ramones and just knowing that you had nailed it. What made you know that you were going to be a Ramone? You’d met them before?

They used to come see my band.

You didn’t know your last name would become Ramone [Marky was born Marc Bell] and they would figure so heavily into your future at the time.

No. I didn’t even know that Tommy was going to leave the band.

There was nothing cosmic. No ray coming out of the sky. Do how did you wrap your head around it? That you were going to become the key member of this iconic band?

Tommy was being bullied. He was sick of the road. He wanted to produce. To be away from them.

Being bullied by John?

Joey started picking on him, too. Tommy was only 5-foot-6, 5-foot-6 and a half. They wouldn’t let him smoke. They were bullies. So fast forward. Tommy was leaving. He suggested to the other three to get me on board. He told Dee Dee that if he saw me in CB’s to ask me. So Dee Dee was the first one to ask me to be in the group. Then it was John. Then there was an audition. There were about 20 other drummers hanging around, but I knew I got it. I heard these songs already in the jukebox at CBGB’s. I knew them very well. I practiced them.

Did you have a conception of how fast they were played?

I saw them. I listened to a lot of jazz drummers and I knew how they held their sticks. They didn’t use their arms hardly.

So it’s almost an illusion. It seems like you’re pounding but it’s fast.

If I was going to use my arms for the whole hour and 20-minute set, it wouldn’t work. If you’re just using your wrist and fingers, it’s simple.

Do you talk shop with other drummers still?

They want to know how I do what I do and I explain to them. They’ll say, I can’t do it. My arm tightens up. I’ll say you’re doing it wrong then. You gotta exercise your wrist and fingers.

I’m going to read you a quote that I wrote down. This is a Phil Spector quote. We’re talking 14 or 15 years after Lenny Bruce died, but he comes in and is still obsessed with Lenny Bruce and he says, “All the true sacrifices were made in the late '50s and the '60s. This is a lazy time out here. Someone else paved our way. I was there.” I was reading then when I was reading your book and thinking you could apply that to pretty much any time. You could apply that to now. You could apply that to something now that you might feel at your age with all you’ve done. Looking at the kids in punk bands with tattoos who don’t have to worry about being beaten up by teddy boys in England or frat boys in America. Do you relate to Phil a little bit more now?

I always related to his politics.

But the feeling like it was an age of pioneers that don’t really exist anymore?

Who is there really? Who’s out there? Where are they?

It’s technology now. Those are the pioneers. That’s the difference. The new Ramones are techies. The new Lenny Bruces are techies.

Will that help them develop social skills? I doubt it. I hope so.

Will it help music?

I don’t know what we’re entering in the next 10 or 15 years, but it will hinder creativity in other artists because of all the piracy and the downloading.

Are the Ramones pirated a lot?

Well, everybody is, but it feels like our fans want to support us. But I’m talking about new bands.

The famous crest and the T-shirts?

All of it. “Hey Ho” and “Gabba Gabba Hey.” But I think that music is going to be stifled because a lot of artists are going to go, "If I keep getting ripped off then I’m just not going to do it."

You’ve definitely broadened your interests or allowed yourself to spend more time on an interest that was already there in terms of cooking and marketing your own spaghetti sauce, which I have not tried but I would like to.

It’s No. 2.

But if you give me the URL, I’ll put it down in the piece where people can get it.

I got my own beer coming out all over America.

You’re not only a survivor in the literal sense, but also a survivor in the sense that you realize there’s more to life than just being a punk rocker and being a Ramone.

We live in a capitalistic society. It’s America. I have the opportunity that if I put out a product, I can give some of it towards charity, which I do with my food. My beer’s going to go to Musicians Without Borders. The sauce proceeds are going to go towards Autism Speaks. I’m happy for that -- that I’m in a position to be able to do that.

Do you think it helped you survive everything? That you had other passions, whereas -- I don’t know. I guess Johnny had other passions, like baseball?

He was a sports fanatic. He liked horror movies. So did I. We used to collect sci-fi posters together.

But you need something else. Whether it’s family or a pet. Alice Cooper golfs.

I like to work on my cause.

Tell me about the end of the book, where you take a couple of pages to list your favorite everything. Favorite producers. Favorite films.

I just wanted people to see what my lists would be.

I’d never seen that at the end of a book before. It was great.

My favorite rare cars. Drummers. So they can get more of an idea of what I like besides just drums.

There was a point where the Ramones became more of an institution in the way that the Grateful Dead or something like that, where you go and see the show and it’s an event, but you’re not going to lay your money on them having a top 10 hit. During this period, you kind of bottomed out and you got sober. You were fired or did you quit?

No. I was let go. By the whole band, not just Joey.

Then you were asked to rejoin four years later. But at the same time, you seem like one of the more stable rock stars I’ve interviewed. What’s the key? Your head is on your shoulders, Marky.

I never smoked cigarettes.

(laughter)

Is it New York? Is it just the way you grew up in Brooklyn?

There was a code in Brooklyn. You gotta be blunt. Upfront. No bullshit. No airs. Be who you are. Stop the crap. Stop the bullshit. When I confronted people who had the airs and the rock star attitudes, I didn’t deal with them. I’d just walk away.

But at the same time you have some flash. You still have that rock 'n' roll thing. You have a good combination of rock style and rock attitude but you don’t seem remotely self-destructive or bitter.

Bitter? For what? No reason to be bitter.

A lot of people write memoirs to settle scores.

That’s the thing. I wouldn’t write a book to be vindictive. I wrote a book to be informative. To be comprehensive. When you write a book to be vindictive it’s so childish, because that book is going to be around forever. You have to live with it. If I wanted to be vindictive, I could be, but not in a book. Not in my book. It’s childish. It’s not the right premise to air your feelings of vendettas towards other people because the general public who are going to buy the book are not going to know the inner vendettas that the band had towards each other.

Arturo and Tommy were still alive when you started?

Yeah, they were. They knew I was writing a book. See, when Tommy died, the book was done already. I would’ve devoted a whole chapter to the guy. There wasn’t time.

Do you feel a weight of responsibility now that all four of them are gone? You take a band like Lynyrd Skynyrd who all go down in one plane crash, or Badfinger. It seems like there was some real money funny business going on that maybe triggered something that was already there and the two guys killed themselves. But the Ramones, like one after the other, what happened?

They succumbed to cancer. Why? Who knows?

People get sick, people die. It’s part of the life cycle. It seemed cruel. This is a band that I love, that you love, that everyone who loves good music loves, and they all died too young.

We were closer than family.

But was it because they didn’t take care of themselves on tour all those years?

No. The thing is this. Joey occasionally dabbled in cocaine and alcohol, but not to a point where he was on skid row. Cancer can affect anybody, from the strongest person in the world to the weakest. It doesn’t discriminate what body it enters.

But four people from the same band within 10 years?

Very ironic. I know that. I think about that all the time. Why? Three. Not one. Not two. Three. And then Dee Dee overdosed.

But you’re still out there. How did you hook up with Andrew W.K. [who sings Ramones classics with Marky Ramone’s Blitzkrieg band]?

Through a friend. Steve Lewis. I don’t know if you know him or not, but he’s responsible for a lot of the nightclubs in New York. So Andrew W.K. was suggested. Andrew agreed to come down to rehearsal and it worked out. He loves the Ramones' songs.

Do you think if the other members were around to see it, they would acknowledge that it’s within the same spirit?

Oh, they’d be very grateful.

You’re literally a flame keeper. And Andrew W.K. is definitely a true believer in rock 'n' roll.

He knows how to engage people.

He’s a little nutty.

I like that because it creates an interest and curiosity. He does it his way. I didn’t want a Joey clone.

The book’s been out nearly a month. Are you starting to get a balance of praise for the actual quality of the writing?

Four and half stars on Amazon. No. 1 for three weeks.

We didn’t talk much about the '90s, which is when things kind of started leaning towards where we are now, where the Ramones are -- I don’t want to say posthumously because you are alive and playing -- but after the band broke up, they were appreciated and you had to watch Green Day, Rancid, the Offspring and Blink 182 take basically this thing that you invented, not in a garage but in a basement or CBGB's or Max’s or wherever, and sell millions and millions of records and play outdoor sheds and arenas. I think you were very frank in saying that it irked you guys a little bit.

Joey got hurt the most because he was the most sensitive.

Not that they weren’t grateful or respectful to you. I think Green Day opens all their shows to this day with “Blitzkrieg Bop.”

Oh, they do, and we were grateful. It’s flattering. Any artist that’s imitated. But what they did is they used our foundation, sprinkled their magic on it, and then started their own bands.

Did you feel like, hey, we’re not done yet?

In ‘96? No. We knew. We had discussed it.

It gave you a couple extra years.

On a larger level, yeah. We did Lollapalooza. The radio started playing us some more.

U2’s new single is called "The Miracle (of Joey Ramone)."

But it doesn’t mention his name in the song.

No. It’s the subtitle. What did you think when you heard that single?

I thought that the dedication was nice, but knowing his intelligence, he could’ve put Joey Ramone’s name in the song. Now if you don’t know the Ramones and what he’s referring to, what’s he singing about?

Right. He could be singing at the Clash.

It’s very generalized. It’s not specific.

You have a pretty good bullshit detector. You can tell who the true fans are and who they aren’t.

Like this guy Morrissey. When the Ramones went there to promote their first album, he wrote the most scathing review of the first album that I ever read. Now, he’s a big Ramones fan and he’s sorry he wrote the review, and Rhino and Warner’s is letting him choose an album [Morrissey Curates the Ramones] that we just put out the songs on. They let him choose the songs on it. This guy who hated the Ramones.

Maybe he didn’t get it yet?

That’s not the point. You either get it or you don’t.

Lester Bangs. When "Exile on Main Street" came out, Lester famously trashed it, and then he ran a retraction of his review saying this is a great, great record. Sometimes, especially when you’re young, you want to be iconoclastic. It’s my tendency to defend Morrissey because I’m a fan. I’m just playing devil’s advocate.

You don’t go back on your word.

There’s a long history of revision of opinion in culture. I don’t think that he knew that a letter he wrote to N.M.E. when he was a teenager-- that he would grow up to be a pop star and every word he ever wrote would be preserved. The larger point is that now the Ramones are a legend and the music has proven to be lasting and powerful, people come around and say I was into them from the beginning. That must be frustrating for you but also gratifying. If it wasn’t beloved, no one would say anything.

A lot of people at the time were afraid of change. That was the problem.

You were opening for Van Halen and Black Sabbath fairly early on.

1978. Wrong pairing. Let’s put it that way. But back then who could we play with? How many bands were around, you know what I’m saying? But anyway. That’s what we were up against. But for Morrissey, all of a sudden, 40 years later, to convince Rhino to put out a song-selected album that he put together? Give me a break.

I guess they just assumed that they would sell records with his name.

I don’t know why they have to use his name.

Well, this is great. Thank you so much for being so generous with your time and the coffee and pizza. As I said, I’m a huge fan. I brought the book if you would sign it.

What I like about [co-author] Rich Herschlag is that he was able to write the book in my voice. That’s important.

Did you actually type with him?

No. I talked into a tape.

But he caught your voice? That’s hard to do.

Very important. A writer can make you sound like you have the King’s English and I don’t.

Shares