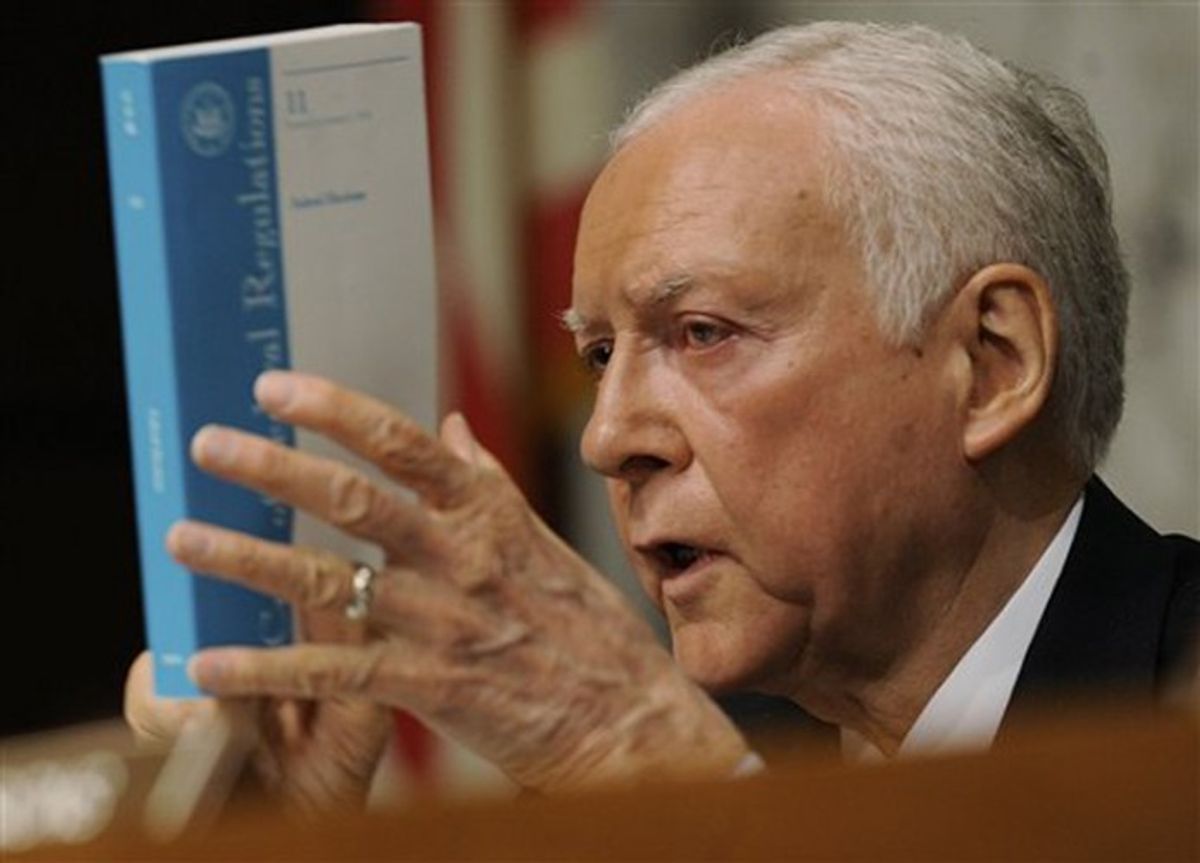

So a couple of weeks ago I noted that Orrin Hatch, Republican senator from Utah, was scheduled to deliver the keynote address at a Heritage Foundation event called “King v. Burwell: Why the IRS Obamacare Handouts Should Lose at the Supreme Court.” Republicans in Congress are all about King v. Burwell these days and are doing their damnedest to convince the conservative justices on the Supreme Court that they should kill the law by ruling that its health insurance subsidies are being illegally disbursed. At the time, I confidently predicted that Hatch would say some untrue things about the Affordable Care Act – things that Orrin Hatch’s past statements about the ACA would directly contradict. And, well… I was right.

A quick recap: the argument in King v. Burwell centers around whether subsidies for purchasing health insurance can be distributed through the 37 state health exchanges set up by the federal government. Supporters of the case argue that one isolated passage in the law clearly forbids this. Opponents argue that the plaintiffs are exploiting imprecisely drafted language in the law and that the clear intent of the legislation was to make the subsidies universal.

A key part of the plaintiff’s case in King v. Burwell is the notion that Congress deliberately wrote the ACA in such a way that it would deny subsidies to states that opted to have the federal government run their exchanges. Congress did this, they argue, in order to provide an incentive for states to set up their own exchanges. There is vanishingly little contemporaneous evidence to support this contention, and plenty of contemporaneous evidence that refutes it. Orrin Hatch, who was in Congress at the time the ACA was drafted, debated, and passed, stepped up to the lectern at Heritage yesterday and gave a full-throated endorsement to this invented history of the healthcare reform law.

Here’s what Hatch said, from his prepared remarks:

The incentive for states to act also could not be more clear. If a state fails to establish an exchange, its citizens lose out on millions—perhaps even billions—of dollars in subsidies. Obamacare’s proponents quite reasonably thought this would lead states to set up exchanges, and would thus accomplish the same result—creation of state-run exchanges—that Congress could not achieve through direct command.

Congress also recognized, however, that some states might not take the deal. Thus, it provided a backstop. In yet another provision of Obamacare, Congress instructed that if a state does not set up an exchange by the January 2014 deadline, the Department of Health and Human Services shall “establish and operate such Exchange within the State.”

Crucially, however, Congress did not similarly provide that subsidies would be available to subscribers enrolled through a federally established exchange. And the reason is obvious. If subsidies were available under both state and federal exchanges, states wouldn’t have incentive to create their own exchanges—to expend time and resources setting up an online insurance marketplace—because the subsidies would come either way. Fewer states would create exchanges, meaning the federal government would have to step in and create more exchanges of its own.

The restriction of subsidies to state-established exchanges was thus a key element of Obamacare’s entire cooperative federalism scheme. Without this restriction, the end result would have been a federally run health care market, a result unacceptable to several key Obamacare supporters, including Senator Ben Nelson of Nebraska, whose vote was essential to passage.

There’s one bit in there I want to drill down on: Hatch’s claim that it was “obvious” that Congress drafted the law the way it did in order to push states to build their own exchanges. He should know, right? He was in Congress at the time, after all, and it was only a few short years ago. So let’s go back and see what Hatch had to say then and compare it to what he’s saying now.

In the summer of 2011, the Treasury Department promulgated a regulation that clarified that consumers on both the state and federal exchanges would be eligible for subsidies (this regulation is at the center of the King case). In December of that year, an outraged Orrin Hatch fired off a letter to then-Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner objecting to the proposed regulation. In Hatch’s view, Treasury was making a change to the law that only Congress had the authority to make.

Here’s what he wrote, with emphasis added:

I appreciate that some in your agencies and in the Administration might have found the language creating the premium credits, as passed by both the House and the Senate and signed by the President, problematic, since it precludes the application of premium credits to any federal exchanges. I would suggest that the failure to draft this language differently was the result of the highly partisan nature by which PPACA was pushed through Congress. Whatever the case, if the wording and effect of section 36B should somehow be different, then legislation is the appropriate means of changing section 36B. The legislative function, under the Constitution, is exclusively granted to Congress.

What Hatch was referring to was the fact that the ACA was passed via budget reconciliation. After Scott Brown won the special election for Ted Kennedy’s seat and stripped the Democrats of their 60-vote majority in the Senate, Democratic leaders used reconciliation to prevent Republicans from filibustering the bill. The legislation passed, but because it was passed using reconciliation, it did not go a conference committee, which is typically where imprecise and sloppy legislative language is cleaned up and refined. In this letter, Hatch endorsed the idea that the subsidy question arose out of a drafting error (a “failure”) that resulted from the ACA’s unorthodox route to passage.

Now, however, he’s arguing something very different – that Congress wrote the law this way purposefully and with clear intent. Not only that, he’s arguing that this intent was “obvious.” And that’s what he has to argue because the GOP’s best hope for seeing the Affordable Care Act destroyed rests in part on their willingness to lie about their own experience with the healthcare law.

Shares