“I do not believe that the president loves America. He doesn’t love you. And he doesn’t love me. He wasn’t brought up the way you were brought up and I was brought up through love of this country…. With all our flaws, we’re the most exceptional country in the world.”

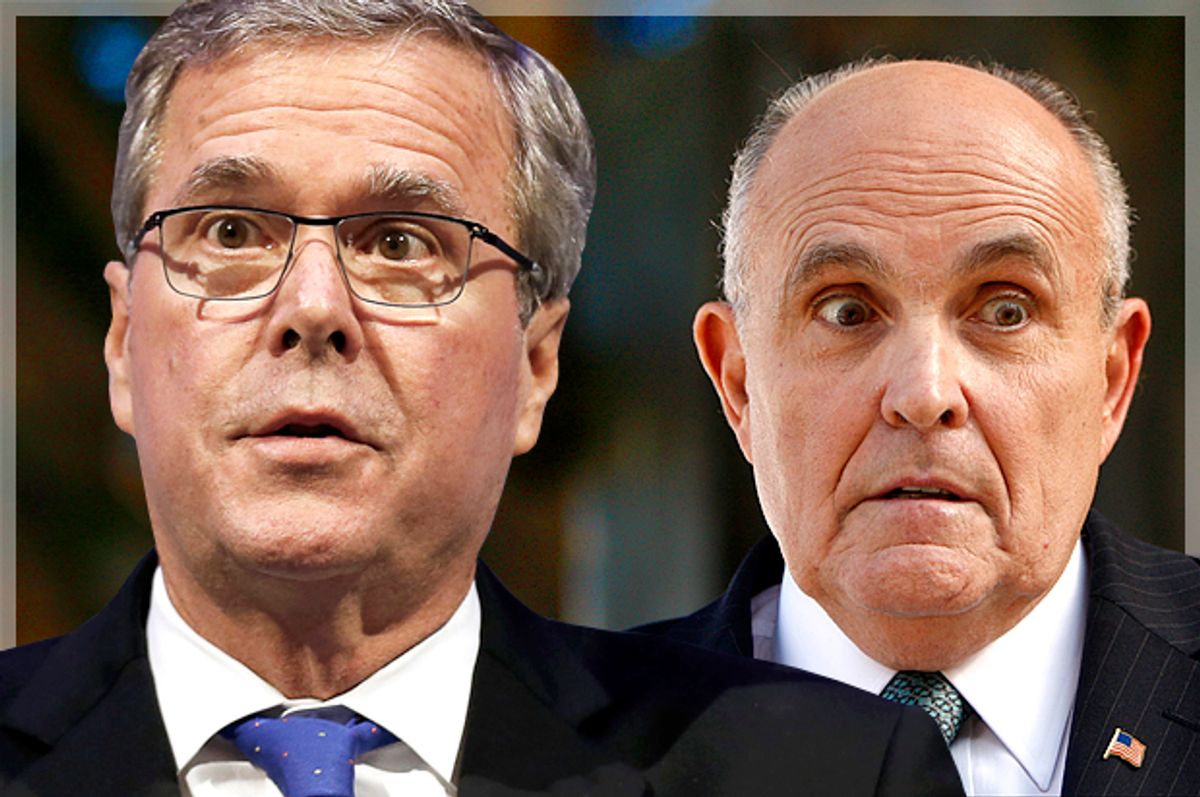

That is Rudy Giuliani, New York’s former mayor, speaking at a Republican dinner in Manhattan earlier this month. Many readers will recognize these now-infamous remarks.

Here is Jeb Bush, the all-but-certain Republican candidate in 2016, speaking to the Chicago Council on Global Affairs a few hours earlier:

“America does not have the luxury of withdrawing from the world. Our security, our prosperity and our values demand that we remain engaged and involved in often distant places. We have no reason to apologize for our leadership and our interest in serving the cause of global security, global peace and human freedom.”

And here is President Obama, introducing his administration’s 2015 National Security Strategy , an annual announcement as to how America’s defense and foreign policy cliques intend to get us through the year:

“Any successful strategy to ensure the safety of the American people and advance our national security interests must begin with an undeniable truth—America must lead. Strong and sustained American leadership is essential to a rules-based international order that promotes global security and prosperity as well as the dignity and human rights of all peoples. The question is never whether America should lead, but how we lead.”

There it is, readers. You have your lumpen rightists, who have acquired more power than seemed possible a few years ago but still face the knotty problem of stupidity. You have your mainstream rightists, polished and clever, intent on staying the expansionist course and persuading us it is best for all. On the foreign policy side, these people remain the right’s true center of gravity.

And you have your neoliberals, ever dressing up the rightists’ agenda as the progressive thing to pursue. This, the Williams-Sonoma crowd, is possessed of an egregious righteousness. They are the heirs of the Cold War liberals, those gutless many who assumed whatever shape necessary to avoid confronting American paranoia, reaction and aggression, usually out of sheer self-interest.

These are the alternatives before us as we look to a presidential campaign and a new administration. It is an interesting choice. We can have exceptionalism, exceptionalism or exceptionalism. One cannot wait to vote.

One cannot wait for the media to wring fantastic distinctions out of the field of candidates for the 2016 presidency. How awful it must have been for those condemned to life in one-party states until freed through our leaders’ commitment to spreading liberty and “human freedom” everywhere.

We live through a significant passage in American history. This bears only brief explanation.

Chosen-people consciousness arose in England prior to the 17th century crossings. It was a belief, never a thought. There are those who still profess to believe, but the belief long ago passed into the sphere of mythologies. There exceptionalism remained, I would say until September 11, 2001.

The airborne attacks in New York and Washington revealed the myth as myth. The astonishingly abrupt revelation that Americans are exceptions to nothing was the primary reason that day so shocked most of us.

Since then the wheel turns again: The myth is now two things. It has hardened into an ideology, and it is something closer to a psychological disorder, whereby the leadership—which has most to lose from the collapse of the exceptionalist version of history, not you and I—incessantly insists on the efficacy of the idea in the face of all evidence.

This is how I read our moment. An exhausted mythology is finally overwhelmed by new realities as the entire world beyond American shores presents them, with exceptions such as Britain, Australia and Israel.

The American leadership faced a choice in 2001: It could re-imagine the nation’s place in the global community or eschew all imagination in favor of holding to the past. The choice was on the table briefly but proved too stark. The job of thinking lost to the job of believing. Rudy Giuliani, Jeb Bush and President Obama merely articulate the standing preference among the powerful.

Each of these three have something to tell us. Let’s consider these lessons one at a time.

*

Giuliani was named “America's mayor” after the 2001 attacks in his city, but the buffoon within was always destined to break the surface, as it has regularly since he stepped aside in late 2001. D.H. Lawrence had a term for this kind of pol. He called them “temporarily important people.” It is perfect for Rudy.

What is Giuliani doing talking about love in public places? This was my first question. The answer is that he does not mean love. His true accusation against Obama was that the president shows signs of ideological deviance. This is dangerous in America—for all of us. Think about it: Every conversation we have now is freighted with semiological signals as to whether or not one is a believer.

Giuliani reminds me of a couple of things. We are not a strong nation at this moment in our story. We are merely powerful—another, lesser thing altogether. The leadership is weak (as in incapable of new thinking) and frightened (as in having no idea of how to face a future that does not look much like the past).

No general in a uniform, no one in camo fatigues, no senior spook at the NSA, no hyperpatriotic politician with a flag pin on the lapel should be mistaken as strong because he or she recites the exceptionalist catechism. They seek shelter in the past because facing forward in the post-September 11 era is too fearful a prospect.

Giuliani is a blunt instrument, but do not miss this point, either: Not too many of us ask others to pass some kind of love-of-country test, but very many of us, maybe most, are more subtle exceptionalists. Cold War liberals felt called upon to prove their anti-Communist bona fides. Most of us live according to a variant of the same imperative.

*

The interesting thing about Jeb Bush’s speech in Chicago was what he felt called upon to prove. Most comment has focused on his “I am my own man” effort to distance himself from George W.’s catastrophic foreign policy decisions, notably the Iraq invasion in 2003. Fair enough, one cannot blame him for trying.

My focus landed on the theme of departure, a policy different from what Washington puts out now. His insistence on the new was partly an early rendition of campaign stumping, O.K., but Bush implicitly acknowledged the fundamental malfunction of policy, too: We need the new because what we have does not work.

It turned out, of course, that Bush meant the new in the nothing-new. “Greater global engagement,” one of his core policy principles, does not mean innovating how America addresses the world—identifying root causes of conflict, for instance. It means a stronger NATO and a strategy to defeat “Islamic terrorism” not by diplomatic or any other reasoned means but an effort “to take them out.” (I have always found the use in high places of a phrase that originated among criminals to be telling.)

“Our words and actions must match,” Bush declared. Ah, a return to the Enlightenment ideals we ignore but hollowly profess. Nothing doing. He means when we say we are going to invade or bomb somebody unless, unless, unless, we must make sure we do so.

Beware always when an American leader talks of advancing freedom and liberty abroad, and the point holds with Bush’s notion of “liberty diplomacy.” Sure enough, Bush defined this as a foreign policy that asserts uniquely American notions of individualism, liberty and other such things. “If we withdraw from the defense of liberty anywhere,” he said, “the battle eventually comes to us.”

New? This is straight out of the 18th century. At the very most recent, it is a restatement of Wilson’s dictum, “The world must be made safe for democracy.” The great William Appleman Williams put this in its place decades ago: Safe for our democracy, no one else’s, is the intent. And it is Bush’s, should he become Bush III.

Upsum: Elect this man and Americans will resume just where they left off—or thought they left off—on January 20, 2009. Bush recently announced a new crew of 21 foreign policy advisers, and the truth of what he has to offer lies in the names. Nineteen of these people served in either the Bush I or Bush II administrations.

No need to do any better than Maureen Dowd, the New York Times columnist who covered “Rummy,” Cheney and others among the regents who took George W.’s presidency more or less out of his hands:

“It’s mind-boggling, but there’s Paul Wolfowitz, the unapologetic designer of the doctrine of unilateralism and pre-emption, the naïve cheerleader for the Iraq invasion and the man who assured Congress that Iraqi oil would pay for the country’s reconstruction and that it was ridiculous to think we would need as many troops to control the country as Gen. Eric Shinseki, then the Army chief of staff, suggested.

“There’s John Hannah, Cheney’s national security adviser (cultivated by the scheming Ahmed Chalabi), who tried to stuff hyped-up junk on Saddam into Powell’s U.N. speech and who harbored bellicose ambitions about Iran; Stephen Hadley, who let the false 16-word assertion about Saddam trying to buy yellowcake in Niger into W.’s 2003 State of the Union; Porter Goss, the former CIA director who defended waterboarding.

“There’s Michael Hayden, who publicly misled Congress about warrantless wiretapping and torture, and Michael Chertoff, the Homeland Security secretary who fumbled Katrina.

“Jeb is also getting advice from Condi Rice, queen of the apocalyptic mushroom cloud. And in his speech he twice praised a supporter, Henry Kissinger, who advised prolonging the Vietnam War, which the Nixon White House thought might help with the 1972 election.

“Why not bring back Scooter Libby?”

No need, I would say. There are enough evil-doers among Bush’s 21 advisers to propel him nicely backwards should he take back the White House for the Bush clan.

*

Once upon a time I might have been disappointed to see how abjectly Obama’s latest National Security Strategy conforms to the orthodoxy. But that was long ago. This paper is a good case for casting the neoliberals as descendants of the Cold War liberals. Obama does not even question the exceptionalist narrative, much less critique it. He stays safely with the matter of how to advance it: “The question is never whether America should lead, but how we lead.”

Actually, Mr. President, that is precisely the question. We are not going to get anywhere in the 21st century until it is legitimate to ask it.

And the answer is no, America should not lead the global community in the 21st century. It could, had it made fewer bad decisions throughout the post-1945 period. But as things have turned out it cannot, and the reasons for this are simple and closely related: It does not know how to lead. It is not equipped to lead even if it had an idea of how to do so.

This is a 29-page document, and I urge readers to spend a little time with it. Certain core truths emerge in its lines and between them.

One is that there is an abiding blindness at work here as to the world beyond American shores—and, indeed, as to the world within them. We cannot see ourselves as we are and, still less, as others see us. We do not understand that our “money politics”—the old Japanese phrase for the corrupted political process—has cost us any claim to leading by democratic example. Ditto Guantánamo, Abu Ghraib and so on in the matter of human rights.

The paper makes much of an American commitment to “a rules-based international order,” and elsewhere reiterates our right to act unilaterally across sovereign borders when we see fit (which works out to be regrettably often). Does Obama’s Washington think others do not notice these gross contradictions?

There is a very interesting section subheaded simply “Values.” This is another of those words that prompts worry when it emanates from Washington. And one finds, as one does all the way back to Wilson, a subtle, carefully conveyed conflation of “universal values” with “the values of the American people.” This is the very purest essence of exceptionalism: We must lead because we are possessed of the providentially given light.

All the Cold War tropes—rational choice theory, game theory, Chicago economics and so on—animate the 2015 National Security Strategy in that the document reveals the American leadership utterly incapable of registering difference, alternative preference or perspective and culture altogether. This simply will not work any longer.

Some phrases are bold-faced in a Churchillian display of determination that, again, conveys nothing so much as self-doubt: “We will lead with strength,” “We will lead by example,” “We will lead with capable partners,” We will lead with all the instruments of U.S. power,” “We will lead with a long-term perspective.”

These phrases have an odd way of making the heart ache, I found as I read them. We are not strong as a nation, we have abdicated the power of example, our capable partners now include the same mix of dictators, crooks and murderers familiar from the Cold War decades and we make most of it up as we go along. Dead on as to the instruments of U.S. power, though: As the paper makes clear, military and surveillance hardware rank first through fourth or so on this list. It is all we know well.

Thirty-odd years ago, the worldly and well-trained Stanley Hofmann, a professor at Harvard, gave an early layout of our post-Cold War choices. “Primacy or World Order” is a book that made much clear to many people (and one rarely out of my mind these days).

As the title implies, we will have to rest our decisions on different priorities, Hoffmann predicted. We must accept a plural world, we must achieve consistency in what we do, we cannot regress, the American public must be given a voice in foreign policy it has never by tradition had, we need to develop “maximum feasible understanding.” The alternative will be chaos.

Have you looked out the window lately? Now you know why I continue to honor the late Stanley Hoffmann.

One question remains. Where are the foreign-policy progressives, such as they may be?

I cannot find one. If there are any—in the executive departments, on Capitol Hill—they lie very low. But the only way to defeat the orthodoxy is if they come out of hiding, and it seems the only way they will is in response to prevalent, well-voiced objection. It should be obvious where this places the onus of a heavy burden.

For as long as America has had a foreign policy—let’s say 140 years or so—the exceptionalist consensus has proven extremely durable beyond all differences on the domestic side. So it is now. We have got done little of what Hoffmann argued persuasively to be our new imperatives. The worst of it is, from both sides of an aisle that has never meant much in foreign policy, we are now on notice that the commitment in our names but not by us remains headlong in the other direction.

Shares