I have pretty much ignored the story of Jameis Winston, the star quarterback from Florida State who is certain to be among the first players selected in this year’s NFL draft – and who was accused of sexually assaulting a fellow student in December of 2012. I don’t follow college football, and the initial reporting on the assault allegations made the case sound “murky” or ambiguous. We use those words too easily talking about these things, don’t we? What happened two winters ago between Winston and an FSU freshman named Erica Kinsman – yes, his accuser has now come forward and identified herself – seemed like a classic “he said, she said.” It might have been about drunken miscommunication or a celebrity athlete’s sense of entitlement (I told myself) more than “rape-rape,” to use the infamous phrase of Whoopi Goldberg.

After seeing Kinsman speak for herself, in the biggest news-making moment of “The Hunting Ground,” Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering’s powerful documentary about campus rape and its consequences, I now view my reluctance to read or think about the Winston case in different terms. On one level it was a defense mechanism. On another it was the result of a cultural scrim that gets pasted over cases like this, a cloak of denial, obfuscation and phony mystery. In fairness to myself, that defense mechanism and the Cloak of Bogus Uncertainty can be found everywhere in our culture. Those were the very forces that led ESPN commentators Skip Bayless and Stephen A. Smith to describe the rape allegations against Winston as “terribly unfair,” suspiciously timed and quite possibly the result of some sinister conspiracy, after they surfaced late in 2013.

We see that ESPN clip in “The Hunting Ground,” not long after hearing Kinsman tell her story, and at least for me it touched an acutely painful nerve. Sure, Smith and Bayless are just a pair of TV jock-sniffers whose instinct was to rally around an alpha-male sports deity. But the combination of entitlement and bogus certainty and low-information sexual paranoia – coming from two guys who would certainly tell you, in earnest tones, that rape is a terrible crime that should never go unpunished – spoke volumes about the nature of the larger cultural problem. I watched that and I felt ashamed.

I want to circle back to that question of shame and collective responsibility, both because I can feel some male readers nervously hauling out their #NotAllMen tweets and their MRA FemiNazi-backlash talking points and because I believe that watching “The Hunting Ground” can be an eye-opening experience for many men, as it was for me. But I also want to make clear that this film is more about female agency than male agency, and that its real subject is the way young women have organized to share their experiences, tell their stories and confront the deeply entrenched bureaucratic resistance that has shamed and defeated so many assault victims who dared to ask for justice and accountability. Erica Kinsman’s testimony is made more potent by the fact that she is one example among many. The true stars of “The Hunting Ground” are Annie Clark and Andrea Pino, who both survived sexual assault as undergraduates at the University of North Carolina and went on to form End Rape on Campus, the activist group that has spearheaded numerous anti-discrimination complaints and lawsuits based on the handling of assault complaints at colleges and universities.

That defense mechanism I mentioned earlier is not limited to men who don’t want to confront the widespread problem of rape and sexual assault and its consequences, although men are highly vulnerable to that form of collective blindness. It’s also not limited to college administrators (a dishearteningly large percentage of them female) who are eager to protect their brands by suppressing allegations and sweeping assault cases under the institutional carpet, although such tactics appear to have been universal among schools of all kinds from coast to coast. But those phenomena have undeniably fed into each other in toxic fashion, producing shameful delusions like the Smith-Bayless moment on a grand scale. Those guys had no idea whether Jameis Winston had raped anybody, and they may well look back on that broadcast now with regret. But instead of treating the charge as an unproven question of fact – as they would have treated an investigation of shoplifting or drunk driving or murder – they proceeded from the assumption that it was unlikely and bizarre on its face, and probably reflected some hidden agenda.

In fact, that’s a good way of summarizing the net effect of our collective confusion and discomfort when it comes to rape and sexual assault – a confusion that gets magnified in the hothouse atmosphere of a college campus, where a cadre of young people is isolated from their families and communities. An entire class of violent crime, which turns out to be distressingly common on campus, has been ignored, denied, willfully misinterpreted or depicted as some kind of impenetrable mystery. Many young women, as we see in “The Hunting Ground,” have now taken it on themselves to dispel the aura of shame and doubt and self-blame that so often surrounds this issue. Their example is inspiring, but there’s still a long way to go.

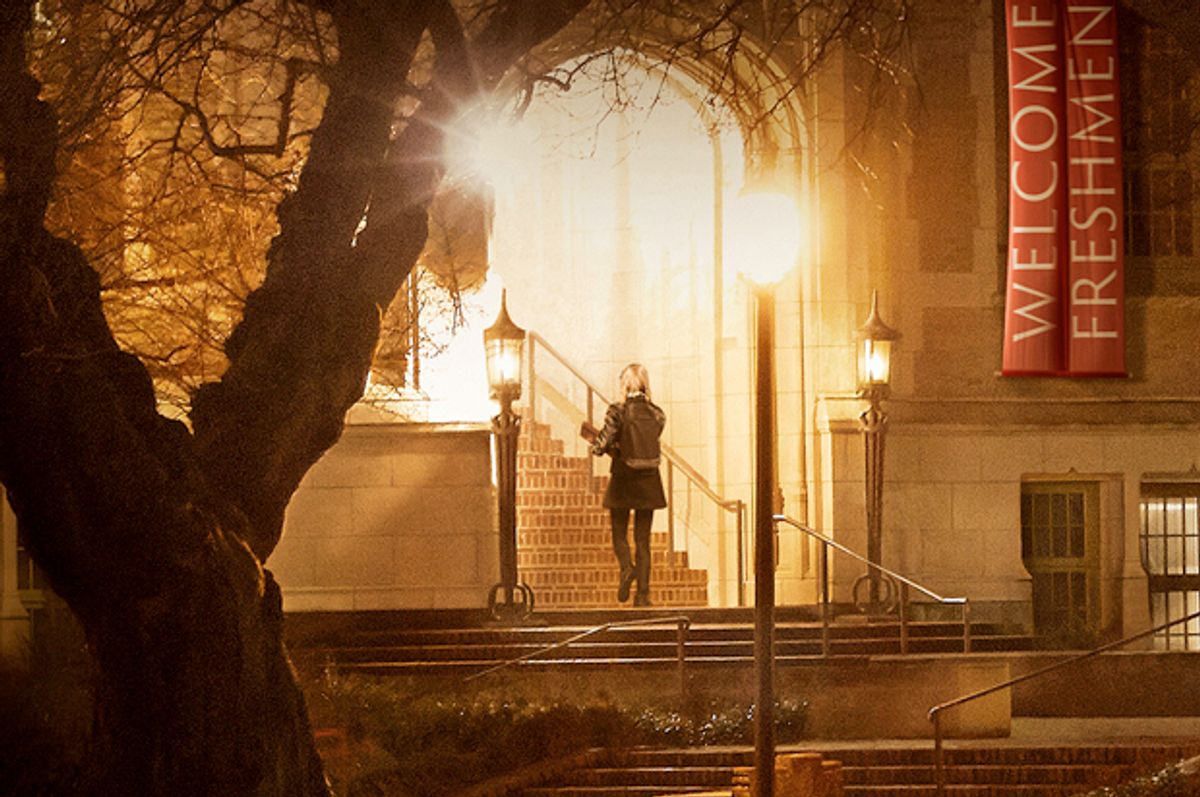

If “The Hunting Ground” is not especially artful cinema, and could have benefited from a broader cultural context, it performs an invaluable service by attaching an impressive range of compelling human faces and human voices to the issue of campus sexual assault, which is sometimes presented as a controversial or divisive “feminist issue.” In this context, how you feel about such a label, or a gender-studies term like “rape culture,” is irrelevant. It’s about watching and listening while one young woman after another, using her real name, tells us a clear and straightforward story about being raped or assaulted by another student and about what happened later, which invariably involves the school administration doing its utmost to make the whole thing go away. These women come from Arizona State and Harvard Law School, from Berkeley and Michigan and Swarthmore, from the University of Tulsa and from Saint Mary’s College, a small Catholic school in Indiana.

At first, the story of Winston and Kinsman may seem anomalous, since it involves not merely a famous student-athlete but quite likely the biggest name in American collegiate sports. But Dick and Ziering make clear that in other ways it is all too typical. Kinsman told both FSU officials and the local police in Tallahassee that Jameis Winston had taken her to his apartment in a semi-conscious condition, quite likely after drugging her in a bar, and then had pinned her down on his bathroom floor and raped her, while she repeatedly told him to stop. Even Winston’s roommate, Kinsman says, could see that she wasn’t into it and told Winston to stop.

Kinsman says that the Tallahassee police detective assigned to her case, who happened to work for an FSU athletic fundraising organization on the side, advised her not to press charges. (She ruefully says that maybe she should have taken his advice.) The cops never interviewed Winston, his roommate or the cab driver, never requested surveillance video from the bar, and allowed the rape-kit evidence to languish in limbo for 10 months. (The DNA turned out to match Winston.) To the surprise of absolutely no one, Winston was never arrested or indicted, and this past December he was cleared of violating Florida State’s internal student conduct code. His academic record remains clean; his only criminal charge was a citation for shoplifting crab legs from a supermarket. He will soon be a millionaire. Erica Kinsman, who at the time of the incident was taking a science-heavy course load and hoped to go to medical school, has dropped out.

To grab the devil by the horns for a minute, of course we cannot know for sure whether Erica Kinsman or any other woman in “The Hunting Ground” is telling the truth. But allowing for that possibility in any individual case, and insisting that something as serious as a rape investigation be based on evidence, is quite a different matter from shrouding the question of rape in general in a penumbra of epistemological doubt, which is pretty much what our society has done. Yes, false rape accusations do occur, and every such case that hits the media serves to strengthen the complex weave of the Cloak of Bogus Uncertainty. But whatever the men’s-rights crowd may claim, there is no evidence that claims of rape are qualitatively different from reports of other crimes: Something like 95 to 98 percent are likely to be true.

If you want to go with the Bill Cosby hypothesis that this is all some massive feminist long con, a scheme to bankrupt patriarchal institutions and seize power, be my guest. But the cumulative power of all these young women, from different races, different backgrounds and different parts of the country, coming forward to tell their stories is highly convincing. Their stories are all different, but they tend to follow a familiar pattern. First they endured an unexpected and traumatic sexual assault by a fellow student, often a man they knew and believed they trusted. When they mustered the courage to report the incident, they were treated by the administrators of their schools – the people empowered to serve in loco parentis and to supply moral and intellectual leadership – as a troubling management problem. They were coaxed and cajoled and threatened and, of course, swaddled in the Cloak of Bogus Uncertainty: What were you wearing? How much did you drink? Did you send him the wrong signal about your friendship? (One woman says she responded: “If sex was going to be introduced into our friendship, a good time to do that would be when I was awake.”)

Campus rape and sexual assault, like every other aspect of college life, has been studied for decades, and while the force of this film does not lie in statistics, they certainly help underscore the point. Roughly one in five undergraduate women is likely to become a victim of sexual assault, a proportion that appears virtually unchanged since the 1970s. Few of those cases are officially reported, and administrative expulsions resulting from sexual-assault charges are so rare that many large schools report single-digit numbers, or none at all, in recent years. Jameis Winston may have gotten special treatment because he was a star athlete, and there is little question that student-athletes and certain infamous fraternities are overrepresented in campus rape reports. But it does not follow that Erica Kinsman’s case would have turned out differently if her accused rapist had been an unknown chemistry major instead of a football player – except that the media would never have heard about it or been interested.

Young women, as the ingenious activist movement pioneered by Annie Clark and Andrea Pino has made clear, are not content to wait for men to police their own behavior, or for college officials to take their moral responsibility more seriously than their P.R. image. That movement has already altered public consciousness, and is likely to have a profound effect on the future of college life. But none of that relieves men from the responsibility of recognizing and confronting their own ingrained and delusional ideology surrounding the issue of rape. This should be utterly obvious, guys, but no one is claiming that all men are rapists or potential rapists. The vast majority of sexual assaults are committed by a small subset of the male population, perhaps 3 or 4 percent. That is still way too many rapists, and as a group men have not done enough to reject them, shun them and stop them.

Jameis Winston’s roommate, if we believe Erica Kinsman’s story, tried to stop Winston from committing a rape, but gave up and allowed it to continue. Instead of suspending their judgment on a grave criminal charge, the ESPN sportscasters assumed that a charismatic star with a “Magic Johnson smile” could not possibly have committed a crime of sexual violence. Too many of us, too much of the time, have shaken our heads and walked away from “ambiguous” situations, as Winston’s roommate did. We have sought refuge in conscious or unconscious notions of women as hysterical and incomprehensible beings who don’t know what they want. We have been all too willing to fling the Cloak of Bogus Uncertainty over a painful issue that demanded clear sight. The time for all that is long over.

Shares