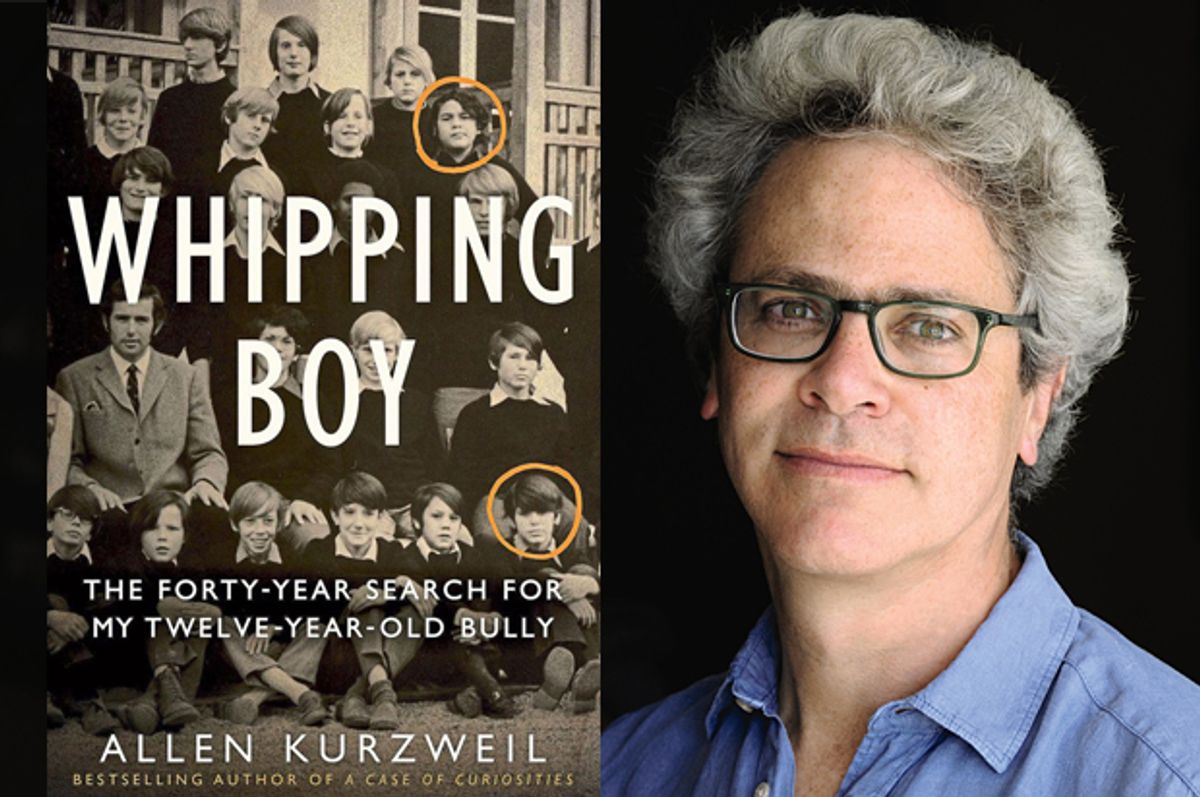

It’s safe to say that Allen Kurzweil doesn’t let sleeping dogs lie. The author undertook a global, decades-long search to find his childhood bully before he was even aware that it all might add up to something beyond personal redemption (or revenge). The resulting book, “Whipping Boy: The Forty-Year Search for My Twelve-Year-Old Bully” is by turns probing, dead-serious and buoyant -- it’s a gripping work of sleuthing and personal memoir. There’s a Monty Python quality to the entire endeavor, and there’s no doubt that the story would make great musical theater.

But “Whipping Boy” is a harrowing book, too. It will leave anyone who was ever treated cruelly as a child asking themselves if they would ever have the nerve to face up to that bully. In many ways, it’s about ripping off the layers of adulthood to the very core -- to find that child still there, just waiting for discovery. Not just the child inside the victim, but the child inside the bully, too.

We spoke to Kurzweil from his home in Rhode Island about the pain of digging into the past, the slippery quality of personal memory, and the sweet taste of revenge.

Bullying is a somber topic. When I first heard about the book, I thought it would be this really intense psychological journey and very, very dark. The book, though, is full of these funny and gleeful moments. Was it fun for you to write?

The easiest parts of the book were a joy to write and fun. But the darker aspects were tremendously difficult. I was rescued from the time I spent exploring those moments of humiliation and anguish by the outrageous probability of Cesar’s adult activities. So yes, by the time I sat down to write the book, there were parts of it that were really, really fun to piece together. The journalist in me loved those aspects of the story that lingered on the preposterousness of Cesar’s professional life. But the final portions of the writing, which were those moments when I really was digging deeper into the anguish that precipitated the inquiry in the first place, were very challenging and did not come easily. I think I came to it backwards, in that I tiptoed around the subject of the bully and of Cesar and whether or not I would write the book as a book. It was only when I found myself in a law firm with 14 boxes of criminal discovery materials that I realized there was very clearly a book in this search. I think the notion of bullying and particularly the genre of memoir writing is predicated on this soul-searching, anguish-filled presentation of self, which is not something that comes naturally to me. I tend to be somewhat whimsical in nature. So there is a bit of dissonance between my temperament and the subject I chose to write about.

Many of us have had bullies. Clearly one of the things that really helped you in writing this book is that other people who had had bullies were cheering you on and they were willing to go out of their way to help you find this guy.

That was one of the amazing and unexpected dividends of this research. I’ve never before pursued a subject where people were not only so willing, but eager to assist me in my research, not because of any journalistic confidence, but because they had an allegiance to me by virtue of the motivating force behind the search. Almost without exception every one of my informants had had a Cesar of one kind or another in his or her past.

Those experiences, a lot of people kind of bury them. How much of this was really a part of your adult life? How much did you really think about it? Was it kind of hidden back there and you had to open the box on it?

Both. I had rendered Cesar into harmless anecdote. He was just a story to tell at a barbecue or a dinner party, almost for comic relief. But I think that that was a defense mechanism for the deeper trauma and I think what has surprised me, subsequent to the publication of “Whipping Boy,” is how there’s this entire contingent of people who have suffered childhood abuse who sublimate or who sweep it under the rug, and then suddenly find themselves resurrecting those childhood memories while reading “Whipping Boy” and then getting in touch with me. I’m in my mid-50s and folks in their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, I mean I’ve gotten letters from grandmothers in their 70s, who grew up assuming it was not OK to carry that childhood suffering into adulthood. So they did try and forget it, overlook it. But I have to say the minute the subject comes up, out come the names of childhood persecutors, out come the stories of this and that. I did a reading last week here in Providence, and yet again someone had to raise his hand, and basically it became a session where everyone named his or her bully. This guy stood up and said, “When I was growing up, Ted Danson tied me to a radiator with a rope and told me I better figure out how to get out of it before the heat started to come on.”

On a more serious note, there’s a Russian woman who was abused as a 6-year-old who’s asking my counsel whether she should hire a detective -- a 72-year-old grandmother. The most incredible thing is I’ve gotten three emails from guys my age who responded favorably to “Whipping Boy” because they used it as an opportunity for the first time to acknowledge that they had been mercilessly bullied by Cesar. So one of them told me, “I’ve finally told my wife about what happened.” For all of the anti-bullying intervention programs, I don’t think there’s much effort made to acknowledge the connection between an older generation of parents who were bullied and the cyberbullying and all of these anti-bullying initiatives that are currently being promulgated and put through. There’s a virtue to actually trying to create a program in which, instead of distinguishing how cyberbullying is so different from what happened to us as parents, as kids, it might behoove us to try and dig deeper to the universal aspects of humiliation that the parents and children all suffer, even if the technology has changed.

In some ways Cesar, I hate to say this, but he did you a favor by being this bizarre character -- in literary terms.

He was a gift, in literary terms, but also I would argue even beyond that, emotionally. If it had not been for Cesar, I don’t think I would have burrowed as deeply into earlier traumas of my early childhood. By participating in an act of vandalism that really was a precipitating force for the search, which was the loss of my father’s watch. He enabled me to spend far too much time, sitting at my desk reflecting on what it all meant, and resurrecting memories of my dad. If I had to rewrite the opening of the book where I refer to him as a menace and a muse, I think I would also say that it was a mitzvah, it was a blessing, that he has given me an opportunity to write about something of importance I might not otherwise have explored.

The setting of the boarding school at the beginning of the book is kind of an unusual setting, with all these kids who are from all over the world. How do you think that that particular setting impacted what happened and the torture that you endured at that time?

There’s two responses that come to mind. First of all, I don’t think that the kind of torment to which I was subjected was unique to Aiglon. If you had gone to any of the other local boarding schools, or even in the United States in the 1970s with hazing and abuse, etc., the sort of nature of that I don’t think is unique to Aiglon. However, Aiglon as an educational institution unquestionably is anomalous. It was, for good and for bad, a totally insane education institution. It’s not nearly as rogue in its organization as it was back then. But back then, it was this extraordinarily eccentric combination of military-style, Etonian, rank-obsessed public school, in the English sense of the word, coupled with this free-spirited, free-loving, early 1970s, Buddhist, spiritual pedagogy of its founding headmaster, who was a vegetarian, asthmatic, who somehow managed to combine this insane 36-page rulebook with a kind of laissez-faire attitude that you would never, ever be able to pull off today. I liked a lot of it. I obviously loathed the time I had to spend with Cesar. But I found it incredibly fun to be kicked out of the school for three days and told to hike around the mountains with a couple of other kids with no surveillance whatsoever by adults as an 11-year-old. Obviously that would never happen today.

I think that from a cinematic point of view, Aiglon is unique, it’s got those incredible vistas and weird foods. But as far as kids being bullied I think that was pretty commonplace; I say this with knowledge now gleaned from very heated and lengthy series of exchanges on the Facebook alumni page in the wake of the publication of the book. There were stories that come out in the Facebook page that are much more concerning than the one I tell. And then there’s a whole range of people who are very defensive about the reputation of the school, and challenge that perspective. So it’s a somewhat polarizing subject. But I think that the particular situation of a particular dormitory I was in, unfortunately encouraged or turned a blind eye to the abuses that Cesar and some other kids were inflicting on the smaller students. [brief interruption] The story that I tell is specific not only to the location or to the school, but to the specific year in which it took place. Because a year later there was a new housemaster and much less of the kind of torment that I received.

Could you tell what was particularly scary about Cesar to you, aside from the things that he did?

I think it was that he managed to balance his menace with a kind of seeming good-natured quality. He was a jokester in so many contexts and then he would turn and he would be a jokester at someone’s expense. When I was around it was always at mine. So he had a capacity to control the actions of other people around him as well. This isn’t in the book because I only learned it afterwards; I describe in some detail the manner in which he deployed his sidekick, this henchman, Paul. Paul was very much a part of the abuse, but I never blamed Paul. It was always Cesar who was the puppet-master pulling everyone else’s strings. In fact, I spoke to Paul after the book came out, and everything that he said confirmed exactly what my memories of Cesar had been. Cesar was just a sneak. He was bigger than I was; he had 30 pounds on me. He was relentless.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, he always played, then as now, the victim, despite all these predations. When he stood before the sentencing judge, having been convicted of multiple counts of wire fraud and conspiracy, not only did he protest his innocence, claiming to be not guilty with all his heart and soul, but he basically said that the reason he was able to identify with the victims was because he was the biggest victim of all. Because he had been misunderstood and he’s been wrapping himself in the mantle of his own victimization his entire life.

There’s something very twisted about that.

Yes, very twisted. I tend to avoid the vocabulary of the psychologist. I let others come up with those terms. But yes, the manner in which he will always be a victim, his fiancée abandoned him just because he was convicted of a federal crime, his mother abandoned him at this military-style school, and Cornell betrayed him by not admitting him to the freshman class, and the bouncer at Studio 54 betrayed him by not letting him pass the velvet rope in 1978 -- all of this, he carries a lot of hurt. The prosecutors wronged him by unfairly charging him with a crime he didn’t commit. It was nothing but a contract dispute. He argues that to this day.

He is a very complicated character, much more complicated than I am. He is not the kind of person I have come across before in my limited dealings with the wide spectrum of human nature. It’s clear from the emails I received from kids who have also been abused by him that he had a unique gift for causing emotional pain.

You tend to be a little bit obsessive. You latched onto this and wouldn’t let go, and the results are so amazing. How much trepidation were you feeling the closer and closer you got to Cesar?

You nailed it. For all of the fun I had when I was dealing with the story from a distance, and in the comfort of the archives or the library or with the files, when it came to actually confronting Cesar, it was terrifying. It wasn’t so much the dangers of confronting Cesar the criminal, the convicted felon. It was much more the trepidation of confronting that former 12-year-old. That’s what I found hardest to do. First, there was some trepidation at some point when I had to first talk to him because I didn’t know what his relationship was to some of the more violent criminals associated with this scam, like Richard Mamarella. But once I established that the connections were tenuous at best, I really wasn’t going to find myself in the cross-hairs of a former New Jersey mobster, I was able to challenge him about the Badische fraud. But the things that consumed our last meeting that I had to fly out to California specifically to do, the one that filled me with the greatest fear, was to look at him and say, "Hey, you did a number on me." It sounds silly, but that was the hard thing, resurrecting the 10-year-old who had been hurt, that I found most difficult. That’s the only thing, if I displayed any force or will or courage at all, it was that final conversation.

As an adult, you are protecting that 10-year-old. But you have to be that 10-year-old when you’re facing this guy.

You put it better than I did in the book. I wish I had thought to say point-blank that I had to be the 10-year-old. I came close to saying that at a certain point in the book. I knew enough that I had to defend the 10-year-old, but I didn’t explicitly go on to say that the 10-year-old that I was, and that I still am. I think we do carry those childhood injustices with us, however much we dismiss them, purge them, render them invisible to comic anecdote. I haven’t done research on this, but I know that there are years in our childhood, whether it's as an 8-year-old or 10-year-old or 11-year-old, that are so much more consequential in our development than certain decades of our life. What did I do in my 30s? I could probably fill up a few pages, right? But age 9, 10? Oh my God, those were packed with all sorts of life-changing moments, discoveries.

There is this moment in the book when you are talking to your wife, and your wife thinks you should fictionalize this because she’s worried about you and your decision to make this nonfiction. If you had written this as fiction, I never would have believed it.

I’ll tell you, there’s something very specific that made it absolutely necessary for me. I found myself dealing with outrageous storytellers and liars, they were in their scam writing an extraordinary fiction, which much to everyone’s surprise a number of victims believed. So confronted by liars, how could I then embroider or fictionalize that deception? For the same reason, I didn’t change any of the names in the book. Because the minute I started changing names, and fictionalizing those aspects, it would call into question my own sort of rigor because I was recording an account of other people who were using aliases and misrepresenting, etc. And also, the reason I knew I wasn’t going to fictionalize this, is because there was something unbelievably exhilarating and compelling about the physical evidence that I stumbled upon. In the presence of the government exhibits of a real-life crime, and the extraordinary specificity of the bizarreness of the childhood school that I attended, I just thought it would be foolish to make up what already was so improbable. You can’t make this stuff up, so I didn’t. It wasn’t a terribly hard decision to make. I’m very good at anguishing and going back and forth and being doubt-ridden. I never was terribly doubt-ridden about the fact that I couldn’t render this as a novel. Not once I found out what had happened. So I can see why my wife would want me to fictionalize it, or mask the identity of people, and there were moments when I did try to figure out how I could do this, but you can’t, especially with the unforgiving nature of the Internet, which allows you to figure out very quickly who is doing what and how, when you are talking about a publicly prosecuted case. I couldn’t see how I could change much of anything.

Do you think you’ve healed a little bit from writing the book? Does it make it better in some ways?

Yeah, absolutely. I find the process of writing and publishing healing. There’s no question about that. Has the wound completely disappeared? No, I think those scars remain. I’m not convinced the relationship is over, meaning the story continues in one way or another. I’m looking forward to moving on to other projects. I think that the book rendered me a different person. Not all bullies are created equal. I think Cesar was an outlier as a child, and remains one to this day. Then again, I’m guessing he’d say the same thing about me.

Shares