Is There Nothing to Be Said for Religion?

And yet, of course, there is the other side to the story. The tales of love and compassion, of giving and of sacrifice, of suffering even unto death, all done genuinely by Christians in the name of their Lord. Since we started the downside in England, let us return there for the upside. The earliest antislavery protests started in the New World in the late seventeenth century.

Soon they spread to England, and like many of the American protesters, the earliest antislavery campaigners were members of the Religious Society of Friends, Quakers. The first formal movement was the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, founded in London in 1787. Nine of the twelve founding members were Quakers, the others Anglicans. As is well known, certainly to every schoolchild in Britain, parliamentary leadership was taken over by William Wilberforce (1759–1833), a man who had undergone an extreme conversion to evangelical Christianity and whose whole life was dedicated to what he thought was the directive of his faith. A member of the British parliament, he began introducing bills for the abolition of the slave trade, explicitly basing his actions on his Christian commitment. “Never, never will we desist till we have wiped away this scandal from the Christian name, released ourselves from the load of guilt, under which we at present labour, and extinguished every trace of this bloody traffic, of which our posterity, looking back to the history of these enlightened times, will scarce believe that it has been suffered to exist so long a disgrace and dishonou to this country” (Speech before the House of Commons, April 18, 1791, in Clarkson 2010, 448). It took forty years for slavery to be abolished through the British Empire, and final success was only achieved days after the death of Wilberforce. But without the efforts of these deeply committed Christians, the abolition of slavery in the empire would not have occurred as soon (Hochschild 2006).

Wilberforce and his fellow campaigners—who included the Wedgwood family of pottery fame (to which the mother and wife of Charles Darwin belonged)—could be dreadful prigs at times, as well as often showing a remarkable lack of interest in the well-being of their own native working population (Desmond and Moore 2009). Yet they were not alone in their Christian-driven urges to reform. Elizabeth Fry (1780–1845), another Quaker, labored incessantly for the betterment of the lives and well-being of women in prison. She also founded shelters for the homeless and started a training school for nurses (some of whom were to go to the Crimea with Florence Nightingale). Faced with criticism for her efforts as a woman—a role that stemmed naturally from the equality of the sexes in Quakerism—she found a formidable ally late in life in her new monarch, Victoria. The Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (who so hated German theology) was a notable evangelical and social reformer, one who started by working for the reformation of how the mentally disabled were treated and then went on to play a major role in the improvement of the conditions of workers, especially children, in factories and related occupations. The Mines and Colliers Act of 1842 finally banned women and children from going down the mines, and boys under ten years old were also barred. It took another thirty years before Shaftesbury was able to ensure the elimination of boy chimney sweeps (like Tom in Charles Kingsley’s "Water Babies"), a particularly vile occupation, dangerous in itself—a popular way of getting the wretches to move on was to light a fire under them—and with horrible effects later in life, notably scrotal cancer.

Do we find parallels, stories of light and goodness in the other areas I showed the dark and evil side to religion? Of course we do. The story of Pastor Martin Niemöller (1892–1984) is well known (Evans 2005). A First World War hero, he was a sailor in the U-boats, and he followed his father in becoming a Lutheran pastor. From a conservative background, initially he welcomed the rise of the Nazis, but soon he fell afoul of them over the Aryan policies, becoming one of the founders of the Confessing Church. For his outspoken opposition, he spent much of the Third Reich in concentration camps, Sachsenhausen and Dachau. He is best known for his famous statement that he and his fellows had stood aside and let the forces of evil have their way—they came for the communists, the trade unionists, the Jews, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, the incurables—and then? “Then they came for me, and there was no one left to speak for me.” Pastor Dietrich Bonhöffer (1906–1945) is an even greater Christian hero. Another founding member of the Confessing Church, he returned from abroad to work alongside his fellow Christians. Imprisoned by the Nazis, he died strangled by piano wire for his involvement in plots against Hitler. Always driven forward by his faith, Bonhöffer explicitly saw the imitation of Christ here on earth as our first, foremost, and indeed only obligation. Deeply influenced by the Pietism movement in German thought and tradition, he argued that only by engaging as Christians within the world can we show our true allegiance to our savior. Among those greatly influenced by Bonhöffer was Martin Luther King, Jr. And finally, if you want a third person—or group—there is the story almost too painful to recount of Sophie Scholl (1921–1943) and the White Rose group (Newborn and Dumbach 2007). A small band of Christians—Sophie was Lutheran but much moved by Catholic writing and preaching—they distributed antiwar pamphlets at the University of Munich in 1942 and 1943. Inevitably, they were discovered, condemned to death, and executed. As she walked to the guillotine, her last words were: “How can we expect righteousness to prevail when there is hardly anyone willing to give himself up individually to a righteous cause. Such a fine, sunny day, and I have to go, but what does my death matter, if through us, thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?” (Hanser 1979).

And so to the Catholic Church. Does one talk of Vincent de Paul (1581–1660), who founded charities, who built hospitals, who ransomed galley slaves from the Arabs? Does one mention the great teaching orders, most notably the Jesuits, who founded no less than twenty-eight universities and colleges in America, including Fordham, Georgetown, and Gonzaga? Do not forget Dorothy Day (1897–1980), devout Catholic convert, who served the poor and homeless during the Depression. Or does one speak of Maximillian Kolbe (1894–1941), the Franciscan friar who calmly took the place of a condemned prisoner and died in Auschwitz? Take the Christian Brothers. An Irish congregation, they have spread across the world, founding schools in all of the many countries in which they find themselves. In Canada, rightly, for the abuses that they perpetrated at an orphanage in Newfoundland, they have a dreadful reputation. (All too typically, the archdiocese had been aware of what was happening and simply covered things up until they exploded into the public domain.) Put this against the story of a man I am proud to call my friend, Michael Matthews (b. 1946), who virtually single-handedly has reformed science education by bringing to bear the insights of the history and philosophy of science. He was raised by a single mother in Sydney, Australia, and when he was on the verge of adolescence, the headmaster of the local Christian Brothers school announced that (without cost) Michael would be enrolled as a pupil the next Monday. And he was, and his life was launched—through the dedication of men for whom the life of a Christian was reason enough. No doubt telling this story will embarrass Michael, but I do so to deflect interest in my own parallel story involving the kindness of members of the Religious Society of Friends. My education was paid for by Kit Kat bars, produced by the Quaker philanthropists, the Rowntree family.

Does the Good Outweigh the Bad?

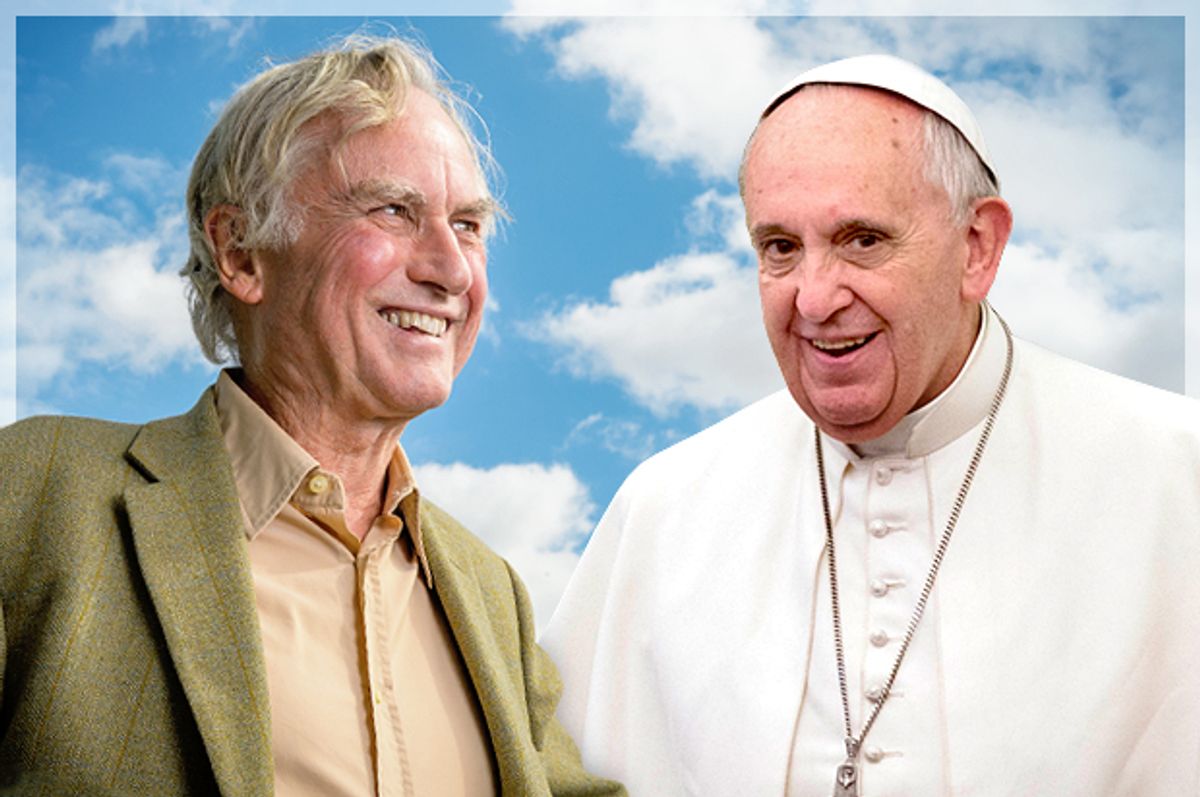

Christians will not be surprised by any of this, the bad and the good. “I do not understand my own actions. For I do not do what I want, but I do the very thing I hate” (Romans 7: 15). We are made in the image of God, but we are deeply tainted by sin. But how are we to evaluate things? Does the good outweigh the bad, or is it the other way? Richard Dawkins will say that the bad far outweighs the good. Many Christians (not all) will say the good outweighs the bad. They will point out also that we are not just dealing with morality, but with culture generally, and this includes the arts. Could one imagine a world without the cathedral at Chartres, without a Raphael Madonna (or for that matter without a Grunewald Crucifixion), without the Bach Passions? Dawkins responds that there is no need of religion for any of this: “the 'B Minor Mass,' the 'Matthew Passion,' these happen to be on a religious theme, but they might as well not be. They’re beautiful music on a great poetic theme, but we could still go on enjoying them without believing in any of that supernatural rubbish” (this was a series of talks and debates organized by the Science Network in association with the Crick-Jacobs Center at the Salk Institute, La Jolla, California, November 5–7, 2006). I confess that I am not entirely certain about this, although admittedly a purely secular and worthwhile culture is possible. My favorite opera is Mozart’s "Cosi Fan Tutte," which is about as non-Christian and Enlightenment cynical as it is possible to imagine. I find "Parsifal" very tedious, and the quasi-Christian mysticism is a major part of what makes it so.

The simple fact is that one is asking an impossible and unanswerable question. What kind of calculus is one to use to weigh Bloody Mary killing three hundred Protestants against the sacrifice of Sophie Scholl in Munich in 1943? Somehow, a simple body count seems highly inappropriate. How does one measure those going to their death absolutely secure in their belief in the hereafter and of God’s love and praise against someone who dies worried and scared and not completely sure, or at least was that way until the last moment—someone like Blanche in Poulenc’s "Dialogues of the Carmelites"? For that matter, how do you measure the death of Sophie on the guillotine against the death of Jesus on the cross? Alvin Plantinga is convinced that the latter is overwhelmingly the greatest act of moral goodness ever. I am not so sure. New Atheists will argue that such calculations are irrelevant. As the example of one child suffering is argument enough against the existence of the Christian God, so the sexual abuse of one child is argument enough against the value of religion. The evils of religion are just too awful, and religion must be abandoned. This is the morally right thing to do. Others, not necessarily all Christians, will argue that evil things are going to happen whatever the state of society—think of what happened in the atheistic societies of Russia and China—and that perhaps on balance religion ameliorates this. The aim is not to eliminate religion but to improve it.

What about Islam?

Are we not missing the elephant in the room? The focus in this book is the Christian faith. Agree if you must that on the evil question it is a draw, or at least that there are arguments for and arguments against. But Christianity is not the only religious faith, and no contemporary discussion of whether religion is a bad thing would be complete without at least a brief look at the religion of Islam. Since the attack on the World Trade Center’s towers, 9/11, a major theme running through the writings of those opposed to religion is that Islam presents a special and particular danger. So insistent is this theme that critics have suggested that a form of Islamophobia is at work, because surely no religion could be this bad, and, even if it is, the skimpy research (to be generous) of the atheists precludes them from having an opinion.

I will not get into that charge here. The New Atheists are pretty ecumenical in their dislikes. The question is whether there is something particularly pernicious about Islam. One thing we can say is that simple blanket condemnations of Islam are just plain stupid. No one can deny that, taken overall in the 1,500 years since the life of Muhammad (c. 570–632), Islam has seen and supported and been part of great civilizations—with law and order, justice, music, arts, literature, philosophy, and, above all, science. As a philosopher and historian of science, I know how much we all owe to the Muslims. In straight philosophy, too, Islamic culture flourished when Europe truly was in the Dark Ages. And if you doubt art and architecture, go to Spain and visit the Alhambra. Better than Chartres? I don’t know, but certainly it is not a silly question. Yet there is ongoing violence. That fateful morning, it was Muslim fanatics who flew the planes into the towers (and who hijacked two other planes). To be balanced, violence seems often directed toward coreligionists as much as toward anyone else, but that compounds the problem. There is something instinctively violent about Islam. There are other aspects of Islamic culture that also seem less than desirable: the status of women, for instance. But—recognizing that this might be another reason for your hostility to religion on moral grounds—let us leave this one. What about the violence issue?

It seems fair to say a number of things (Kelsay 2007). First, perhaps purely because of history, there does seem to be something distinctive about Islam with respect to fighting and territory. It is a religion founded by fighting men, and its early history was very much one of aggression and expansion. In a way, this is in the lifeblood of Islam. (What follows are commands by Muhammad to fighting forces.) “Fight in the name of God and in the path of God. Fight the mukaffirun [ingrates, unbelievers]” (Kelsay 2007, 100–101). This is not a Sermon on the Mount kind of religion. (Many would say, with reason, neither is Christianity.) However, this brings up the second point, that Muslims are not and never have been barbarians. Their fighting forces were never SS units doing their thing in Eastern Europe. The notion of Just War has always been as central to Islam as it is to Christianity. “Do not cheat or commit treachery, and do not mutilate anyone or kill children.” This is from the mouth of the Prophet, although notice that these things are all very circumscribed. Muhammad goes on to give directions about how you should accept surrender and how to treat people you have conquered. “Whenever you meet the mushrikun [idolaters], invite them to accept Islam. If they do, accept it and let them alone. You should then invite them to move from their territory to the territory of the émigrés. If they do so, accept it and leave them alone.” But if they don’t go along with what you want, then things change, and you, as a good Muslim, have a duty to treat them sternly even unto death.

Third, related to all of this, especially with respect to territory, there is a sense that once a part of the world becomes Muslim, it should stay that way for all eternity. After all, there is but one God, and he rules over everything. Our pushing outward with his rule is but doing his will. This, of course, was just fine when Islam was in expansionist mode, but in the last third of its history, it has seen more and more encroachment on its territory. One thinks of the Iberian Peninsula, conquered by the Muslims by 750 and then increasingly lost until the rule came to an end around 1500. One thinks of the British occupation of India, the Raj, with many Muslims under its control, although this was reversed somewhat with the creation of Pakistan. And most recently, one thinks of the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, on land previously owned and occupied by Muslims.

So, fourth, expectedly, there is a divide between ideology and realpolitik. Basically, although one does hear some fanatics making the territorial claim, there is not a major desire in the world of Islam to retake Madrid in the name of the Prophet. But what about Israel, especially given that since the war of 1967, it seems to be in an expansionist mode with respect to land occupied by Muslims? I am not now talking about the rights and wrongs of Israel but about how its very existence sets up tensions for Islam. There don’t seem to be quite the same tensions in Christian lands. It is true that France and Germany have pushed back and forth on the disputed provinces of Alsace-Lorraine, but no one seems terribly concerned to retake East Prussia for the present German Republic. And this is so, for all that the displacement of the Germans in the east seems to have been at least as brutal as any displacements when Israel was founded.

Fifth and finally, there is no one Islamic authority to make decisions in the name of everyone. One can hardly blame Islam too much here. Western Christianity since the Reformation has been divided, and this leads to differences about major moral issues. But it does mean that people like Osama bin Laden (1957–2011) feel empowered to step up and take action when and where they think others are failing or compromised (for instance, by their alliances with the West) or simply taking the wrong course of action. Do note that this does not mean that such people are ipso facto justified by Islam. By its very nature, Islam has always been a religion in which authority is respected and obeyed. That, too, is rooted in early history. The law is not there to be taken into your own hands, and there is the already mentioned concern about a just war. It is hard to see 9/11 falling within these limits. It is here more a question of why these things happen as they do. With fragmented authority, and Muslim state set against Muslim state—think Iraq and Iran—it is little wonder that fanatics step in to take their own courses of action.

So to conclude, the issue here is not about how to deal with the threat of Islamic terror in today’s world. The question is whether there is something evil about Islam, over and above the norm for religion (whatever that norm might be). The answer is that there do seem to be factors that make for violence unique to Islam and that these would be triggered in today’s world. But things are complex, by no means inevitable (given Islam), and there are controlling factors, which may or may not be observed. An atheist will pick up on this and argue that this is yet one more argument against religion, and perhaps an atheist should. Yet note that we have focused only on religion and whether religion is that only or most important factor, and not whether we should take into account things like poverty and jealousy of other nations that seem to be pushing Muslims around. This is surely a question that needs discussion. However, it is not our discussion at this place and at this time.

So, What’s the Answer?

What is the connection between religion and evil? That there is a connection is well taken, hardly a surprise, given the extent to which religion invades our lives in so many respects, personal and public. That the connection is complex is equally no surprise. After that, the matter is still open for debate. Some, like Peter van Inwagen (2011), mentioned earlier, will see overall that religion has been a force for good. Others, like the New Atheist Christopher Hitchens (2007), the subtitle of whose book was "How Religion Poisons Everything," will see overall that religion has been a force for ill. Increasingly, students of human history and nature—represented most recently and most forcefully by the Harvard evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker (2011)—are starting to conclude that (even taking into account the dreadful events of the twentieth century) there has been a significant decline in violence in human history. Pinker is inclined to find the causes in the rise of modernity—the rule of a democratic law-bound state, the development and application of liberal philosophies about the status and rights of individual humans, and the like. Against Hitchens, he argues that religion has on occasions obviously been a force for good, but certainly not uniformly. “The theory that religion is a force for peace . . . does not fit the facts of history.” Perhaps in the end there is no one answer but a host of answers, depending on the circumstances. Better perhaps is the question whether one sees certain trends that tend to lead to good or ill. When the authority of the priesthood goes unquestioned, perhaps there is more scope for ill. When, as Pinker suggests, the role of women is raised, perhaps more kindly factors prevail. Certainly, one might expect a more balanced approach to sexuality and gender roles. That is the best that can be said, but that can still be a great deal.

Excerpted from “Atheism: What Everyone Needs To Know” by Michael Ruse. Published by Oxford University Press. Copyright © 2015 by Oxford University Press. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares