From 2013 to 2015, the 113th Congress of the United States of America did very, very little. One of the flaccid 113th’s most substantial accomplishments, in fact, was simply not becoming the least-productive Congress in American history — an ignominious title held by its predecessor Congress, the 112th. And as perhaps goes without saying, it only did this during the waning moments of the term, and only by the skin of its teeth.

Yet despite its clear record of doing nothing in a time when much needed to be done, the 113th Congress did make its mark on American history in at least one positive respect: It used the so-called nuclear option to severely weaken the power of the filibuster in the U.S. Senate. This wasn’t a unanimous decision, obviously. It was something the then-majority Democrats did after much hand-wringing and consternation among themselves, and in the face of vociferous Republican opposition.

Still, however slow in coming it may have been, and however much one may have wanted the “nuclear option” to go even further, the move was freighted with symbolism and deserving of credit. On the substantive level, President Obama would never have been able to confirm as many federal judges as he has without it. And on the symbolic level, invoking the nuclear option was even more important. Not simply as a response to unprecedented GOP obstruction, but as an implicit acknowledgment from Democrats that American politics was changing, and that they’d have to change, too.

If you’re wondering why I’m reminiscing about the halcyon days of late-2013, it’s because of something California GOP Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the majority leader in the House of Representatives, said to NBC’s Chuck Todd over the weekend. When Republicans were in the Senate minority and had the filibuster as their only weapon, McCarthy and his fellow Republicans saw it as a crucial bulwark against reckless majoritarianism. But now, you see, things are completely different.

Before we get into the specifics of McCarthy’s argument, though, let’s remind ourselves of its context. For the past month or so, Democrats and Republicans in the Senate and the House have been warring over a bill to fund the Department of Homeland Security. The most hysterical and nativist members of the GOP base only want to fund the DHS so long as it doesn’t carry through President Obama’s recent and controversial executive actions on immigration. And Democrats in the Senate, hoping to save the president from having to veto “homeland security” legislation, have predictably resisted a vote on any funding that comes with strings attached.

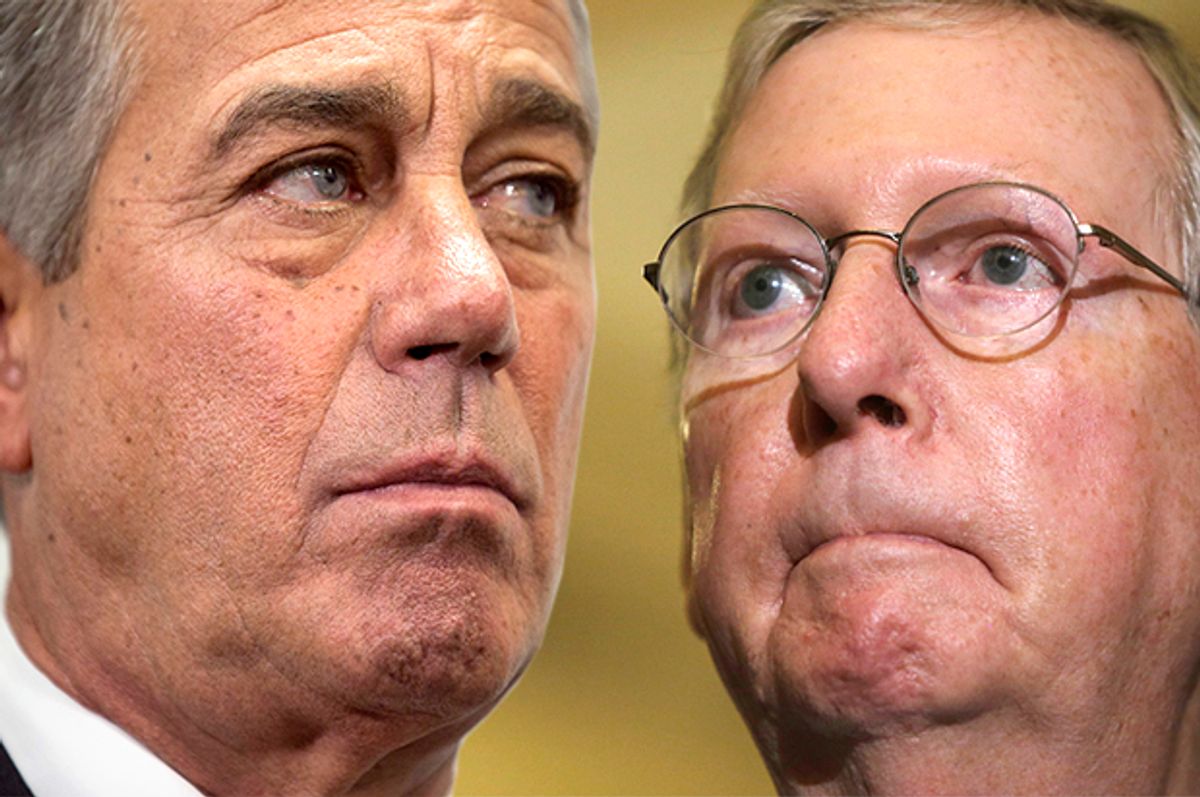

The DHS’s funding was set to expire last Friday. But because Republican leadership knew that causing another shutdown was a political loser for them — especially if its ultimate goal was to increase deportations — they planned to pass a three-week funding bill to give them some time to come up with a better solution. As the majority leader in the House, corralling and counting the votes for the three-week bill supported by Speaker of the House John Boehner was a central test of McCarthy’s competence. He failed it.

The GOP eventually was able to cobble together a bill to fund the DHS for one mere week rather than three. But throughout the media and across the political spectrum, the House GOP’s inability to pass its own plan was seen as a shocking embarrassment. As you’d expect, national attention and ridicule was mostly trained on Boehner. But McCarthy and others in-the-know were well aware that he deserved much more grief than he’d actually get. And to think that none of this would be happening if it weren’t for the Democratic filibuster in the damn Senate!

So when McCarthy told Todd this weekend that he wanted to see the Senate majority use the nuclear option again, it wasn’t entirely surprising. And when he defended the position with talking points that sounded quite a bit like those used by Democrats in 2013, it was less surprising still. He was right when he noted that the filibuster is “not in the Constitution,” and he was right to complain that there’s something screwy when a bill that’s supported by 57 out of the Senate’s 100 members can’t even get brought up for an up-or-down, yes-or-no vote. If only McCarthy had been around back in 2009-2015, he might have said something. (He was, and he didn’t.)

Tempting as it may be, however, it would be a mistake to focus exclusively on McCarthy’s hypocrisy. Because in the filibuster case, the dynamic we’re watching unfold right before our eyes is more complicated, and more important, than the usual bullshit of a politician. After all, the political realm has been rife with unashamed opportunists since time immemorial. But if GOP leadership in the Senate eventually decides to take McCarthy’s advice — and there’s reason to suspect they will, sooner or later — it’ll be something very new indeed. And not just for the Senate, either.

To understand why the fate of the filibuster is so drenched with significance, it’s necessary to take a step back and look at one of the macro-level shifts that is both destroying and remaking American politics: The rise of ideological conformity within the Republican and Democratic parties, and the concurrent increase in the overall electorate of ideological polarization. These are “big picture” issues that have become the chief focus of many talented experts’ careers; so I won’t even try to lay it all out in this piece. But the McCarthy example gives us a decent place to start.

As Ian Millhiser explained in a must-read piece from just before the 2013 government shutdown, and as Matt Yglesias grappled with at length in a good recent essay for Vox, the U.S. system of government is consciously designed to fail in the absence of compromise. Not compromise in the “why can’t we all just get along?” sense, which assumes the problem is recalcitrant individuals, but compromise in the sense that bipartisan agreements are needed if anything is to get done. Granted, if one party has the White House and a stranglehold on Congress, the bipartisan imperative can be ignored. Such moments in American history are not only brief, but few and far between.

With the five years of apocalyptic civil war and the 10 years of breakdown that came first as a notable exception, this setup has worked pretty well for America. There were conservatives and liberals who disagreed vociferously, to be sure. But they were sprinkled throughout both parties; for every conservative Democrat in the South, there was a liberal Republican in New England, and so forth. But around the middle of the century, and especially in the years since the civil rights movement, that crucial ideological heterogeneity has begun to dissolve. Nowadays, the most-liberal Republican is still more conservative than the most-conservative Democrat, and vice versa.

As the parties have become more ideologically uniform, they’ve also become more rigid. The days when a politician could buck his party’s leaders without worrying about expulsion are fading fast, which has led Washington to increasingly function more like a parliament. And that’d all be fine enough if not for one increasingly disjointed but utterly indispensable player in the system — the president. In a parliamentary system, the leader of the government would generally be the leader of whichever party is most dominant in the legislature. But in America, where the president can claim to represent the people’s will just as much or more so than Congress, the flow of accountability is different.

One of the ways this plays out in real life is with a Congress run by one party butting heads with a president who’s a member of the other. As the late and highly esteemed Yale professor Juan Linz explained, the result sometimes — certainly in the case of America today — is not only dysfunction and gridlock, but dysfunction and gridlock whose approximate cause is opaque to most citizens. Since the president is disproportionately credited and blamed by the public, an ideologically uniform party in control of Congress has incentive to muck up the works, knowing that the blame is less likely to land on them than the president. Inevitably, the president and his party become more inclined to look for ways to circumvent Congress altogether.

So, to return to McCarthy, what ends up happening is that the parties come more and more to act like their system is parliamentary, even though it isn’t. Republicans realize that using the filibuster to turn the Senate into a policy graveyard works to their political advantage; and Democrats realize that weakening the filibuster becomes a necessary step to achieving their own ends. And when control in the Senate switched hands while control over the White House didn’t, Republicans realized that the lack of accountability that had done so much good for them before is now benefiting the president. Which puts the filibuster, once again, on the chopping block.

And that, much more than individual hypocrisy or opportunism, is how one ends up in McCarthy’s situation. For people like myself, who see the filibuster (and, arguably, the entire Senate) as an anti-democratic anachronism, the process ultimately reaches an agreeable end. The filibuster’s chances of surviving the next generation are slim. But what’s happening in the Senate right now is happening throughout almost all of the U.S. government — and as we saw during the government shutdown of 2013, or the debt-ceiling crisis of 2011, the changes wrought aren’t always so procedural in nature.

Kevin McCarthy may have just the filibuster in his sights today. But what reason is there to think that something more substantial — say, the provision of subsidies for health insurance; or the funding for Planned Parenthood — won’t be next?

Shares