On the face of papal summer palace, which looms over the public square of a sleepy town near Rome, is a large clock from pre-Napoleonic times. It has one hand rather than two, and a face divided into six hours instead of 12. Its purpose is to remind the world that time passes very differently at the Vatican. Or so I tell myself, as I try to rationalize how the past decade of my life has been consumed by the writing of a single Vatican novel. As a husband and father now approaching 40 years old, I find myself bracing for the publication of a book I began writing as a 27-year-old bachelor.

The novel’s genesis traces to 2003, when I came upon the surprising fact that our modern notion of Jesus’ physical appearance – the bearded, long-haired man of Christian art – goes back to about 400 AD, before which no one seems to have agreed what Jesus looked like. The Bible offers no description, so where had this image come from? Around the same time in history, mysterious relics appeared in the Christian East, purporting to be divine portraits of Jesus not made by human hands. In 1978 a British scholar proposed that the cloth we know today as the Shroud of Turin might in fact be the most famous of these early relics: an image widely known and revered in early Christendom. Even though carbon-dating tests declared the Shroud a medieval fake almost 20 years ago, millions of faithful continue to travel to Turin during the Shroud’s periodic expositions, making this single cloth more popular than any museum on earth. Increasingly, they share a conviction that today’s Turin Shroud is indeed that celebrated relic of times past. Is it possible, then, that the Shroud is the most influential image in Christian history? That, when it first emerged, it was considered so authoritative that all subsequent images of Jesus can be traced to it?

This question would never have spawned a decade of research and writing had it not been for a decision I made alongside it: that the protagonist of my novel would be a Catholic priest, and that my setting would be the world capital of Jesus imagery, where ultimate control of the Turin Shroud now rests: the Vatican.

This was ambitious. I’m not a Catholic; in fact, I’m not a practicing Christian of any kind (though a decade of researching this novel has nudged me closer to becoming one). What I saw, in the question of Jesus’ physical appearance, was an entry-point into the greater mystery of what’s really knowable about Jesus. If we put aside traditional pieties as well as conspiracy theories, what are we left with? A man who is as much a historical construct as our artistic imagery of him? Or is it possible that my fictional priest knew something I didn’t? That it wasn’t his spiritual journey I was storyboarding, but my own?

In retrospect, my interest in searching for a reality beneath outward appearances has an obvious source. My previous novel, "The Rule of Four," had become a media phenomenon in 2004. My coauthor and I had spent the six years after college writing it, during most of which I’d lived in rural southwestern Virginia, supplementing scant wages teaching SAT classes with my wife’s veterinary-school loans, which together were usually enough to spare us from charging groceries on our credit card. Then, suddenly, I was on "Good Morning America" and the front page of the New York Times. What happened after that, I still have trouble understanding.

We became symbols of everything and anything. The NBA ran advertisements showing professional basketball players reading "The Rule of Four." People magazine gave us a prominent review in the “50 Most Beautiful” issue, and the Wall Street Journal followed up with an article about our exercise regimens, so that, at a literary society dinner soon afterward, when I found myself seated beside Jenny Craig of the eponymous weight-loss company, her first words to me were: “Ian, I’ve read all about you. And you’ve done such a good job staying trim.” After USA Today reported that President Bush was reading "The Rule of Four," we received letters of congratulations from congressmen, including the Senate majority leader, which were followed by an invitation to what the Department of Homeland Security called a “Red Cell” session, seeking our input into imaginative ways terrorists might try to reprise 9/11. The longer this continued, the less there was any correspondence between our inner lives and outward appearances. Who I was bore no resemblance to how the world seemed to see me.

Money deepened the problem. Earlier that year, my wife and I had been lucky to qualify for a loan on our used Toyota. Now the first royalty check could’ve bought a Jaguar for every day of the week. When Random House offered $2 million for two more books, to be doled out in payments for years to come, all memory of financial hardship vanished into the mist of unreality that now shrouded my life. My wife and I put a down payment on a large house that seemed, in those heady days of the booming real-estate market, a sound investment. Then we settled down to start a family – and I settled down to work.

For the next five years we would never worry about bills. We would have a nanny. We would enjoy a weekly date night at a restaurant nice enough to offer a separate wine menu. Above all, I would have an almost unlimited budget for researching my novel.

The most important thing I learned about the Vatican during my first year of research was that its reputation for secrecy is largely a myth. Considering that leading newspapers from around the globe send full-time reporters to cover a 108-acre country with a population measured in the hundreds, few stones go unturned. If you want to know what it’s like to be a cardinal inside that most secret of places – a conclave – there’s a book on that. If you want to know what each bishop does inside the Holy See bureaucracy, there’s a book on that. I didn’t realize what a godsend these books were until I found myself needing to know things that even journalists didn’t know or weren’t allowed to report on. For while there were books on those topics too, they weren’t the kind I could buy at Amazon.

In February of 1960, the New Yorker published an anecdote about a scholar working at the Vatican Library who asks a clerk to bring him a particular ancient manuscript. (Fetching your own books at the Vatican Library is forbidden.) The clerk vanishes for a while, then returns with a slip of paper on which is written, “Missing since 1530.” There’s a fat kernel of truth in this story. The search for information about the Vatican is maddening not because that information is scarce but because it’s oceanic, bottomless, centuries deep – and because, just when you think you’re on the cusp of a discovery, you drop head-first into the abyss.

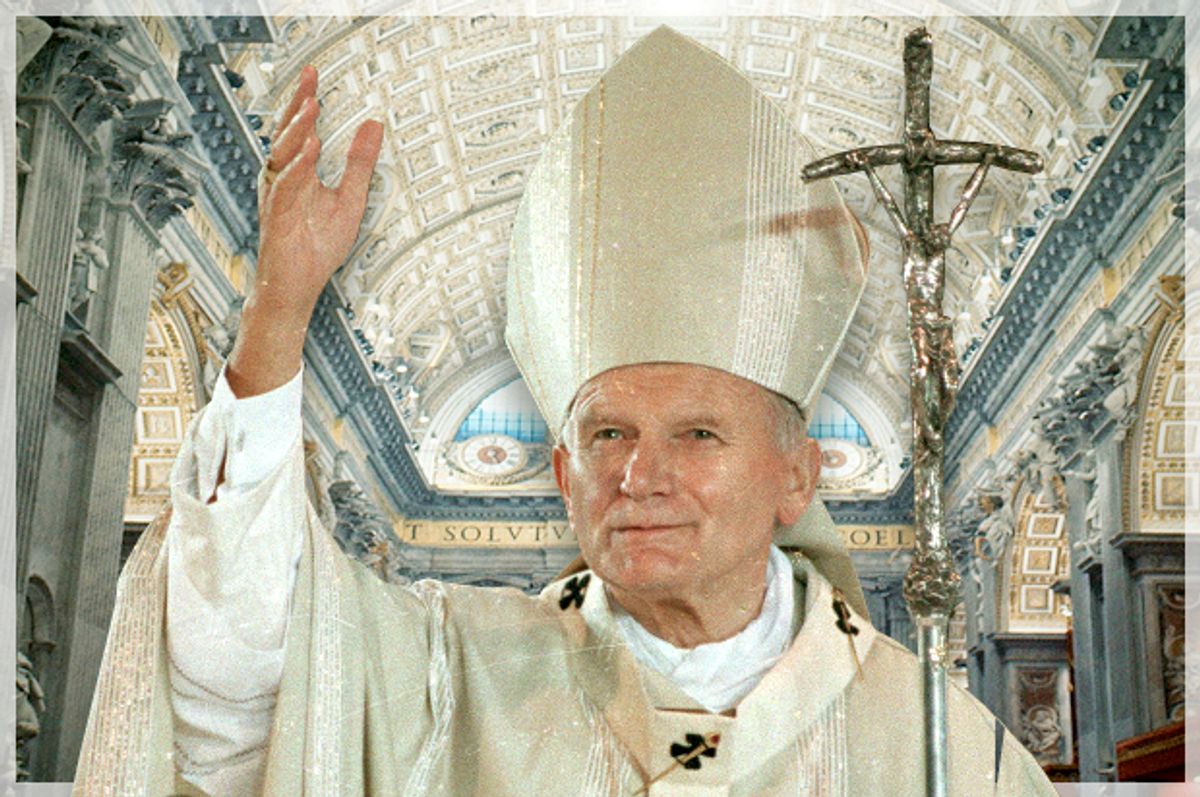

I knew my novel would take place during the waning months of Pope John Paul II’s papacy, and would involve one of his dying wishes for the Catholic Church – to reunite it with Christianity’s second-biggest institution, the Orthodox Church – so I’d envisioned a private scene at his bedside. Like almost everything else in the novel, I wanted this to be grounded in near-photographic realism, and since John Paul was famously open about his private life, I assumed it would be easy to find out what his bedroom looked like.

I was wrong. In the dozens of Vatican coffee-table books I’d stockpiled for image-sleuthing, I found nothing. Nothing, either, in a search of Google Books. I found a few details in the authorized biography of John Paul, but the details were vague: the pope’s bedroom had a full-size bed, a large table of books, and a photo of his parents. Considering that the author of this biography had been given wide-ranging access, these slim pickings were a bad indicator. Without realizing it, I was stepping into one of dozens of rabbit holes I would encounter over the coming decade. The trail led in two directions: down dark alleys into tabloid journalism, and into archived records from past papacies. I went to work.

A bookstore in Paris shipped me a hard-to-find copy of an Italian paparazzo’s memoir of breaking into the papal summer residence around 1980 to shoot pictures of John Paul in his private swimming pool, a book that also contained furtive telephoto shots of John Paul pacing his hidden roof deck at the Vatican. I scoured these pictures but couldn’t find so much as an oblique glance into the pontifical bedroom just below. So I drove to the Library of Congress to dig up microfilm of the Sunday supplement to the Vatican’s own newspaper that had allegedly published, in September of 1978, an article describing every room in the pope’s apartments. But the article turned out to be nothing more than a photo of the pope’s palace taken from down in Saint Peter’s Square – effectively a tourist snapshot – in which each window was labeled “library” or “study” or “bedroom.” In the coming months, while focusing on other tasks, I returned again and again to the question of John Paul’s bedroom. In 2005, after the conclave of that year, Le Figaro had published an excellent map of the private papal apartments, yet about the details of the papal bedroom there was presque rien. A 1971 book by the director of the Vatican Press Office, tantalizingly titled "L’Appartamento Pontificio," yielded even less.

Finally, a stroke of luck: Every pope has a pair of priest-secretaries who live with him in his apartments. A shop in Florence sold me a book written by the priest-secretary of John XXIII, the beloved pope of the early 1960s. In it was the most detailed description I’d yet found of the pope’s bedroom – and it rang a bell. Online, I’d come across a former papal photographer who’d begun selling his old photos in digital format. Among them, I’d spotted a picture of Pope John in a room that was a dead ringer for this description, except that there had been no bed in it. I went back and studied every shot from the roll. At last I found it: the pope standing beside a simple wooden bed that I now recognized as his own.

The walls are plain. There are no frescoes or towering canvases in gold frames. The pope has hung a few photos and small icons, wildly undersized for the almost 15-foot ceilings. One icon is placed so as to cover up a large dark patch where something much bigger was once hung: Apparently it has been a while since anyone repainted the walls. In one corner of the bedroom is a ponderous wooden wardrobe resembling a confession booth. Charmingly, its door has been left open, with a white robe dangling out. A nightgown? Or the pope’s spare cassock? On the floor beside the bed, where the pope curls his toes each morning to greet the world, is a thin rug with zigzag borders and a long tassel fringe. It matches nothing else in the room.

These small details are the ones that change with every papacy. The constants are the plain walls, the checkerboard floor, the simple wooden door leading to the bathroom, perhaps the gauzy ceiling-height drapery over the towering windows. Yet it was the small changeable details that brought me closer to what I’d really wanted to know: There is no papal interior decorator; the gilded lily that is the Vatican stops at the door to this room. The pope’s bedroom is simple, unadorned. Like the bedrooms of other priests, it betrays a life in which material possessions and the cultivation of taste for taste’s sake have been discouraged. It is perhaps the only truly personal place this man has. Feeling gratified and somehow touched, I made a small file for this information and stowed it away. When the time came, I would be ready to write my scene.

In the years that followed, I would buy 600 research books on the Vatican, all of them aimed at solving one question or another in this way. The books would arrive at my door from almost every country in Europe, including the Vatican itself. My private obsession to know the history and appearance of every building within the pope’s walls, and as much as possible about the important rooms within them, provided a welcome distraction from the harder work at hand: understanding what Catholics believe about Jesus. For, in order to do that, I could no longer rely just on books.

Today, looking back on it, the terror of reaching out to my first priest seems overwrought. In the time since that first interview, I have traded phone calls and emails with Holy See diplomats, Vatican priests, Church lawyers, the wives of Eastern Catholic clergy, the Jesuit former editor of America magazine, and the papal caretaker of the Shroud of Turin. That first time, though, unnerved me.

On Jan. 3, 2008, I emailed a priest whose address I had found online. I had chosen him for his credentials. He had studied at the Gregorian University in Rome while living at the Pontifical North American College: this combination is, for American Catholics, the priestly Harvard. He had firsthand experience of Vatican cardinals and Pope John Paul II. He was now dean of an East Coast seminary. And his specialty, evidenced by scholarly books under his name, was the interpretation of scripture. I introduced myself as a novelist writing a Vatican novel from the perspective of a priest. I asked a few questions about his experience as a seminarian. Then I slid in my questions about how priest-candidates were trained to interpret the Bible.

Three hours later came the reply.

Dear Mr. Caldwell,

Puzzled as I am about why one would decide to write about the experiences of a demographic about which one knows professedly next to nothing, I am intrigued enough to offer the following.

Four paragraphs of answers ensued, addressing all of my questions about seminary, and exactly none of my questions about the Bible. Then: “To pursue these matters any further, I would prefer to have the opportunity to discuss your project with you via phone.”

That evening, I called him. I have no record of the length of the conversation. But my transcript, typed as we spoke, runs to four pages. It includes this pregnant single paragraph:

First Year includes synoptic gospels: start with the Resurrection narratives. Professor was very honest about the challenges, that the details don’t correspond, the number of angels, of women, the time of day. Insistent on psychological evidence, that people so disheartened became so strong in faith.

What this means, unpacked, is: first-year men at elite Catholic seminaries in Rome are required to take a class on the synoptic gospels, the first three books of the New Testament – Matthew, Mark and Luke. The word "synoptic," meaning roughly “from the same eye,” is used to describe these three books because of their near-verbatim similarity to each other in many passages, as if we are witnessing the events of Jesus’ life through a single set of eyes. Yet at the crucial moment of all Christian history – the resurrection of Jesus, when he is found to have risen from the dead after his crucifixion – a careful comparison of the synoptic gospels shows that they do not quite agree about several details. These include the “number of angels” found standing by Jesus’ empty tomb, the number “of women” who returned to find that tomb empty, and “the time of day” when they made this discovery. To my deep surprise, these discrepancies were what a professor of scripture was pointing out to a group of future priests, at the most storied pontifical university in Rome, on the very first day of their first year of class.

Surely this was an isolated incident. Even pontifical universities have their share of eccentric professors who refuse to toe the party line; John Paul’s Latin expert, who in his off-hours from Vatican service taught classes at the same legendary Jesuit school in Rome, was notorious for going off-script and criticizing Catholic positions on issues ranging from the modern use of Latin to the Church’s “obsession with sex” and abortion. Perhaps what I’d heard from this single priest was a fluke.

It wasn’t. Other priests at other seminaries reported that their first day of Synoptics went the same way. In fact, some priests felt this was the whole spirit of the class: to challenge men to discard the simple verities of altar-boy life and search in darkness for the way back toward the light. Grope, and plunge onward, and relearn the whole map of faith. I was fascinated. Even a brief glance at the Catholic Encyclopedia from the early 20th century shows a Catholic Church entrenched against modernity: the story of Noah’s flood is still a literal fact, and the only role of modern science is to verify that a big boxy ark made according to the instructions God gives Noah would float quite well, thank you very much. Now, less than a hundred years later, priests were being trained to put scripture under a microscope. To allow, and even insist, that parts of the gospels were not meant to be read as factual history. I was mesmerized by the potential implications of this approach for any understanding of Jesus as a historical figure. So I asked every priest I interviewed to tell me, as best he could remember, the exact books he read in seminary. Then I bought those books, and made them the foundation of my own portrait of Jesus.

Meanwhile, my private life was fomenting revolution in my professional one. In 2005, my first son was born. In 2007, my second. Soon, writing a novel from the perspective of a celibate priest seemed as though it would require an almost total immersion in method acting. Parenthood is the Copernican Revolution of life, a man’s discovery that his universe no longer revolves around himself. It is often suggested that when the real Copernicus discovered the earth travels round the sun, Christians promptly buried their heads in the sand. Yet in a psychological sense, religious people are much better prepared to accept the selfless reorientation around the other that is the basic experience of having children. Most parish priests I’ve met over the past decade lead lives of selflessness that would put even the most devoted biological fathers to shame. Vatican priests, however, are not parish priests.

The typical Vatican priest has no congregation. In place of baptisms and youth ministries and spiritual instruction to the young, he works at a desk. He answers to a bishop, as all priests do; but he does so in a bureaucracy. In short, he is nobody’s shepherd.

This I couldn’t accept. My daily life increasingly revolved around bibs and feedings, specialized knowledge of teething biscuits, seething hatred of hinges and floorboards that squeaked during my escape from a napping child’s crib. As time passed, and I reached the dawn of preschool with my older son, I was spellbound by the act of handing a child keys to the nuclear armament of the mind: how to read. We made trips to the library, forays into children’s literature, nervous incursions into the lawless frontiers of the English language. When another year passed, and the grade-school years came creeping in – the age of PTA and volunteerism – into my life came the weird gripping beauty of the way a soccer game or chess match can reveal a boy’s hidden character. The revelation that my wife and I were coming to know our children through their choices. Day by day I found it impossible to write about anything without somehow writing about this.

There are married Catholic priests in the world. I knew this. They are not merely the rogue ones who occasionally make headlines for keeping families on the side; there are thousands of legitimate clerics who have wives and children with the full blessing of the pope. Many of these men belong to what are called the Eastern Catholic churches, descended from the ancient Eastern tradition in which married men may be ordained. When married priests aren’t celebrating liturgies, or blessing houses for parishioners, or rushing to the hospital to pray with the sick and dying, they’re often pushing their children on swing-sets, cleaning up crayon marks on living-room walls, and admiring the women across their kitchen tables and marriage beds who, on top of all the usual challenges of motherhood, shoulder a parish’s expectations that they and their children will be examples to the community. Almost all Catholic priests know what it is to live on a shoestring, but only a married priest knows how much more threadbare the shoestring seems when the fate of a whole family dangles from it.

I know this, today, because interviews with Eastern priests and their wives introduced me to the private struggle of combining one type of fatherhood with another. They also helped me understand the pressures I would be heaping on my protagonist when I made him a married priest in the overwhelmingly celibate world of the Vatican. “We get an extra $120 a month for each child,” I was told by one priest. “I think they might get a supplement like that at the Vatican too.” He was right. But as a father myself, I had to ask: is that enough to make ends meet? The priest turned to his wife, as if he wasn’t quite sure himself how she did it. She shrugged. “I take odd jobs sometimes,” she said. “When I can. For a little extra money.”

In September of 2008, my wife and I pulled our nest egg out of the stock market and, seeking safe harbor, used part of it to pay down debt on our house. The remainder we earmarked as rainy-day funds for what appeared to be a long incoming storm. The new global recession had thus disguised an ominous sign of trouble closer to home. This was our first tacit acknowledgment that the "Rule of Four" money was not bottomless. That we were beginning to experience cash-flow problems.

Still, my novel was missing a final ingredient: though I had created a Vatican tableau with a vivid Eastern Catholic protagonist, the stakes of the novel needed a final essential force to electrify them. A more emphatic way to talk about sin and redemption.

One night, in a dream, I found myself inside the Sistine Chapel. Above me towered Michelangelo’s Last Judgment. Here it was: the missing piece. In a novel about transgression and reconciliation, what I needed was judgment. Not merely a crime and its investigation, but a verdict of innocence or guilt.

The gospels themselves contain a courtroom drama: Jesus is arrested, tried, convicted. He is judged and brutally punished. This is one of the great symbolic reversals of Christianity: that we, who will someday stand before Jesus in hope of mercy, once judged him ourselves and found him wanting. The freight I could carry with this single idea told me it was exactly what I’d been looking for: I would take my priest – his heart so anchored to his family that he had accepted career compromise and social ostracism at the Vatican for their sake – and threaten him with a judgment that would entail almost unfathomable personal loss. To do it, I would put him in a Church courtroom.

The Vatican has two codes of law. One is a criminal code modeled after the Italian one, which, in turn, was recently remodeled after American practice: innocent until proven guilty, and a trial characterized by competing theories of the crime. Under this code, a Vatican criminal can be sent to Rebibbia, the maximum security Italian penitentiary where Pope John Paul’s would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca, was sent. But this code of law and its stakes – earthly life and death – were the wrong ones for my novel.

The Vatican’s second code, called canon law, governs the Catholic Church itself. Though incapable of sending a man to prison, it is empowered to dole out excommunication, priestly banishment, and under radical circumstances, dismissal from the clerical state: what the non-Catholic world calls defrocking. This is a terrifying prospect with almost impossible implications. In the pages of my novel, I will later compare it to a mother’s being declared childless, or a person’s being declared inhuman, because the mark of the priesthood is, Catholics believe, indelible. A priest cannot actually be unmade; he can only be erased from the roll of the living clergy, shunned, rendered a ghost by the institution that frames the terms of his life as no civil government could. This is, for a priest, the true highest penalty in a canon court, and perhaps the most existential one possible.

Because canonical tribunals work in secrecy, however, it is very difficult to learn how they operate. The most common examples of canonical courts treating grave crimes are from recent priest-abuse trials, so Church lawyers are especially reluctant to share any sort of information, even in the hypothetical, with novelists. Only with great trouble was I able to find the canonical equivalent of a legal defense fund for embattled priests, whose lead attorney I begged for a referral to someone, anyone, willing to help me understand the system. Finally he referred me to a canonist – a specialist in Catholic law – who happened to be writing a book on the subject. After allowing me to win her trust, this woman taught me the ground rules of a fundamentally different system of justice. She also referred me, in turn, to a canon-law expert in Rome so highly placed that I was never even permitted to know his name, a man who stringently took me to task for technical errors, and who reminded me that artistic license could lead to “yet another horrible calumny” by a novelist against Catholicism. Civil court and Church court, I discovered, have this in common: the terror that lawyers wield over the uninitiated. But there the resemblances end.

In a Church trial, there is no presumption of innocence. The accused may not face his accuser. Evidence can be admitted even if it is improperly obtained, so long as the judges feel it has value. The Church may refuse to honor requests for information bearing on the accused’s innocence. Defense and prosecution do not compete; the judges ask all questions. And there is an unfamiliar gray area: between innocent and guilty lies a third possible verdict, “accusations unproven.” Its existence was, to me, unexpected and galvanizing. Though this verdict wisely reflects the challenges of finding a definite truth, it seems at odds with the spiritual needs of the individual Christian to know whether he is accounted among the wheat or the chaff. Without innocence, how can there be vindication? And without guilt, how can there be forgiveness?

Here, at last, my workshop of tools was complete. In my Eastern Catholic priest I had the raw stone, and in the pressures of a canonical trial I had the chisel. In my mind’s eye I had the Vatican, visible down to the most granular level of detail. And guiding my hands I had a half-decade’s apprenticeship in Catholicism. At long last, I was ready to write.

I plunged headlong onto the blank page. By 2010, I had written a quarter of the novel. But now money was becoming a pressing concern. The portion of our nest egg we had reserved for a rainy day was eaten through. Sensing that I was close to rounding the corner, I asked my accountant about the legality of cashing out my retirement account. Legal, she advised. But not wise: a home equity loan would be better. Yet we both knew that no bank would extend such a loan to a writer with no income to show in his two most recent tax returns. Against counsel, I began withdrawals, projecting that they would be enough for my family to live on until 2011. By then, I would have finished a half-manuscript, a contractual milestone for which Random House would pay me for the first time in more than five years.

All went according to plan. In late 2011, I returned to New York with the finished half-novel. None too soon, either; with the bottom of our retirement accounts in sight, only one source of funds remained, and it was the Rubicon we must not cross: our children’s college savings.

Yet I had overlooked something. Blindly, inconceivably, after seven years of work on a novel about Christianity, I had failed to take into account the role played in human life by forces beyond our control.

The publishing world was in straits. Earlier that year, the second-biggest bookseller in America, Borders, had filed for bankruptcy. My editor returned with the news that I would not be paid. Instead, Random House would exercise its option to terminate my contract for failure to deliver on time. This was, in a world where authors routinely finish books long after contracts demand them, staggering. Even more staggering was the news that Random House’s lawyers would pursue repayment of the signing money they had issued me as far back as 2004. My editor, a Random House employee herself, vowed not to let this pass. It was cruel. I had been working hard, and in good faith, and she knew it.

But the lawyers now held a power beyond any realm of art or reason. These were hard times, and cash was king. My literary agent was forced to sail into the headwind of the most unfavorable publishing market in memory, in order to find my half-manuscript a new home. Four major publishers vied for the rights, but none could venture the sums of better days. I made Simon & Schuster my new home, but almost half of my new contract with them would be diverted to reimburse Random House for what had been only the initial payment of my old one. The money that remained would somehow have to keep my family afloat.

There is an old pagan phrase to describe a writer’s gravest sin. Deus ex machina. “God from the machine.” An ending in which the author, unable to find a plausible resolution to the problems he has created for himself, calls for the arrival of a god to descend on the stage and resolve all.

But at the Vatican, every play must end with a deus ex machina. God takes the stage before the beginning of the first act, and adjudicates every ending. The author, if he chooses any other way, is guilty of failing to know his subject.

According to canon law, there is no legal authority in Christendom higher than the pope. His power is “supreme, full, immediate, and universal.” He may overturn the verdict of even the supreme court of Catholicism. In the words of the code itself, “No appeal or recourse is permitted against a sentence or decree of the Roman Pontiff.” This majestic, breathtaking absolutism is an emblem of the far greater, far more mysterious potency of God, author of law and source of judgment.

So, as the trial comes to a close, the Eastern priest waits to hear the verdict. He waits, and waits. How does the story end? What becomes of the man in the darkness who, with everything he loves at stake, convinces himself to grope and plunge onward? The man who believes, heart and soul, that he will come out of present darkness and emerge into future light?

I have spent twelve years in the midst of the gospels. Enough time to be able to recognize their echoes in art and in life. As I write this, my finished novel is emerging from the press. As publication day looms, the question returns: how does the story end?

As it started, of course. It is, and has always been, a matter of faith.

Shares