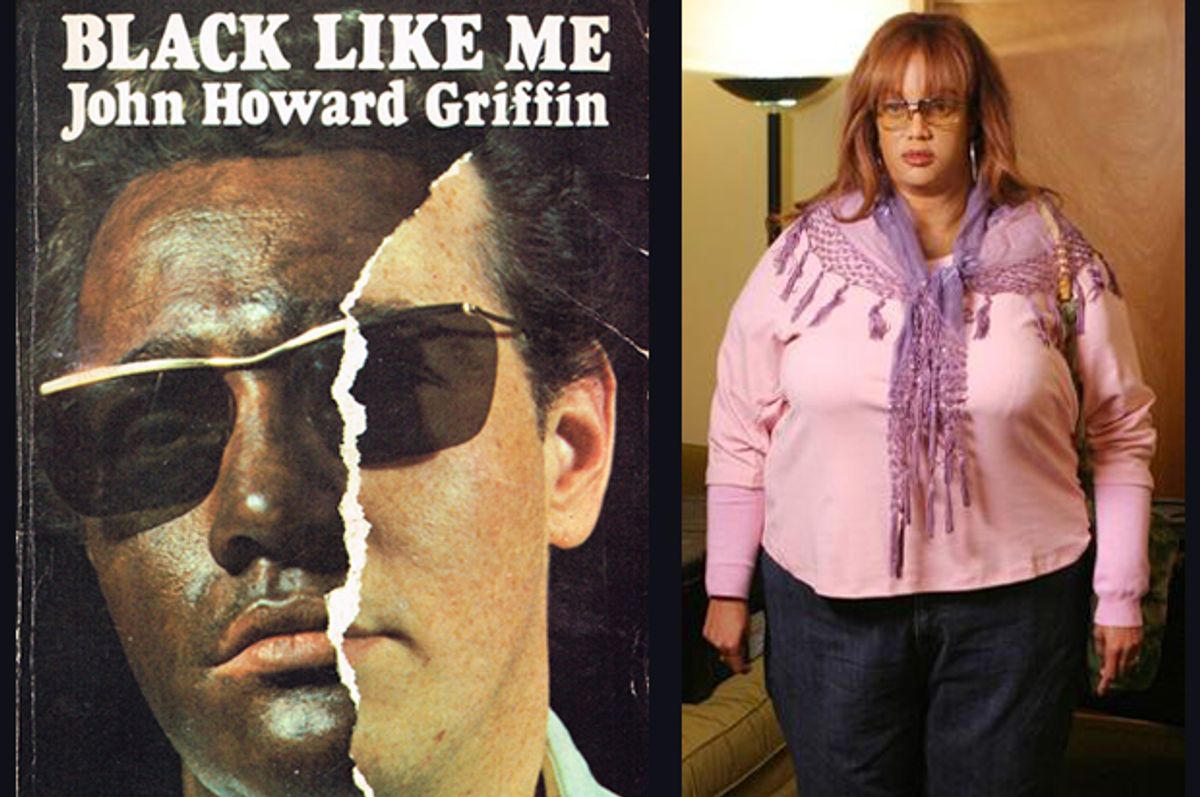

It’s been more than 50 years since the white journalist John Howard Griffin medically darkened his skin and embarked on a tour through the Deep South pretending to be black (a tale he chronicled in the book "Black Like Me"), but Griffin’s brand of immersive stunt journalism is thriving. Despite the preponderance of people writing about their own lived experiences, the media is awash with tales of privileged people conducting “social experiments” in which they adopt the trappings of a less privileged existence and pose for the camera, asking, “Does your oppression look good on me?”

BuzzFeed reported this morning on a white, Christian woman, Jessey Eagen, who decided to wear a hijab—a head covering worn by some Muslim women—for the 40 days of Lent and blog about the experience under the hashtag #40daysofhijab. “I personally know what it can feel like to be an outsider, and I wanted to remind myself of that, so that I can better love all people, no matter what they look like,” Eagen told BuzzFeed. She’s also considering a plan to “darken” her skin color in order to understand the experience of black- and brown-skinned Muslims.

Eagen is by no means the first person to undertake the “hijab experience.” Only a month ago, BuzzFeed produced a video of four women who were asked to “participate in an experiment”—wearing a hijab for a day. The video asks the women to divulge their own prejudgments about women who wear headscarf, then follows them around as they engage in their usual tasks (eating lunch, riding the subway, going to the airport) before ending on a note of uplift and facile revelation. “As a woman you should be able to wear whatever you want,” says one of the women, “and if that’s what you want to wear, then that’s what you should wear.” The video was released just days before three Muslim students in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, were murdered by a white atheist—a crime many suspect was motivated by anti-Muslim hatred.

One popular type of experiment involves men adopting certain aspects of a woman’s daily experience. Isaac Fitzgerald, a reporter for BuzzFeed, wore makeup for a week and discovered that people notice what’s going on with your face and judge you for it. A man created a fake female profile on a dating site and discovered that men can be aggressive and harassing on the Internet. Or there’s the straight BBC radio personality who walked around an English town holding hands with a male friend in order to discover that homophobia exists. Or supermodel Tyra Banks who donned a fat suit to discover that society is hateful toward fat people.

Politicians love to engage in these experiments as well. The popular “Food Stamp Challenge” sees political leaders attempt to live on as little as $1 a day in order to better understand the experience of poverty and hunger. During his unsuccessful campaign for California governor, Republican Neel Kashkari spent a week in Fresno, California, pretending to be homeless and unemployed. The wealthy banker (he spent millions of dollars from his own fortune on his campaign) arrived in Fresno by bus with $40 in cash and an artfully duct-taped backpack in order to look for a job he didn’t need and eat food from homeless shelters to prove a point about California’s economy. (Whatever point he was trying to make, he failed spectacularly and lost the election.)

What all of these experiments have in common is an overly simplistic understanding of human experiences that reduces identity to interchangeable parts. A hijab might make a woman appear to an outsider to be Muslim, but despite Jessey Eagen’s husband’s confidence that his wife’s experiment will lead to “understanding what it feels like to be a Muslim woman in middle-America,” no piece of cloth can stand in for a lifetime of experience. Eagen’s hijab won’t bring with it actual belief in the tenets of Islam, nor the experience of a community reviled by much of the United States’ political establishment and subjected to untold police surveillance.

Eagen has what no hijab-wearing Muslim woman has: the choice not to be reduced to a single article of clothing. Similarly, Isaac Fitzgerald has the choice not to wear makeup—and not to be judged for that decision, as women so routinely are. The BBC journalist can choose to express his true sexuality without fear of street harassment. Middle-class and wealthy politicians can choose to eat as much as they want. It’s the absence of choice that makes societal oppression real. These experimenters offer only a pale simulacrum of that reality, and one that the media has no justification for packaging up for our viral consumption.

And these experiments aren’t without harm. They reinforce the idea that readers or viewers won’t believe that oppression is real unless it’s mediated through a “neutral” observer. Thus we have a straight man “proving” the existence of homophobia and a thin woman “proving” the existence of fat-shaming. But the best evidence is easily obtained by simply listening to and believing the testimony of the people who are actually affected by such bigotry. By pretending otherwise, media outlets that engage in or encourage these experiments perpetuate the notion that being white, male, straight, middle-class, housed and able-bodied are the default condition of humanity. No one asks a black woman to speak definitively about the white experience. Why should we tolerate the reverse?

I’m sure that many of the purveyors of this kind of social experiment have good intentions, as Jessey Eagen seems to. They want to promote empathy, and they probably don’t mean to take up the space that could more judiciously be used talking to and listening to people who actually experience the oppressions they borrow. But this type of empathy-seeking is out of date and immature. It reminds me of another book that appeared around the time of "Black Like Me," Harper Lee’s "To Kill a Mockingbird," in which Atticus Finch teaches his children that “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view — until you climb into his skin and walk around in it.” Surprised by the overwhelming reaction to the beloved but hardly radical or sophisticated narrative of race in 1930s Alabama, Flannery O’Connor remarked, “It's interesting that all the folks that are buying it don't know they are buying a children's book.” Playing dress-up in other people’s cultures is a children’s game, and it’s time for the media to grow up.

Shares