Alice Dreger grew up in the sort of household that, according to contemporary political logic, shouldn’t exist: Her parents were Polish immigrants, “industrial-strength Roman Catholics” and anti-abortion activists who also considered themselves feminists and keen believers in the American ideal of free thought and speech. They gave to the poor, took in an unwed mother and adopted a mixed-race foster child. They also subscribed to science magazines and encouraged their kids to question authority. Not surprisingly, in Dreger they raised at least one atheist, a woman who “felt the tension one surely must feel when being simultaneously taught the importance of a specific dogma and the importance of freedom from dogma.”

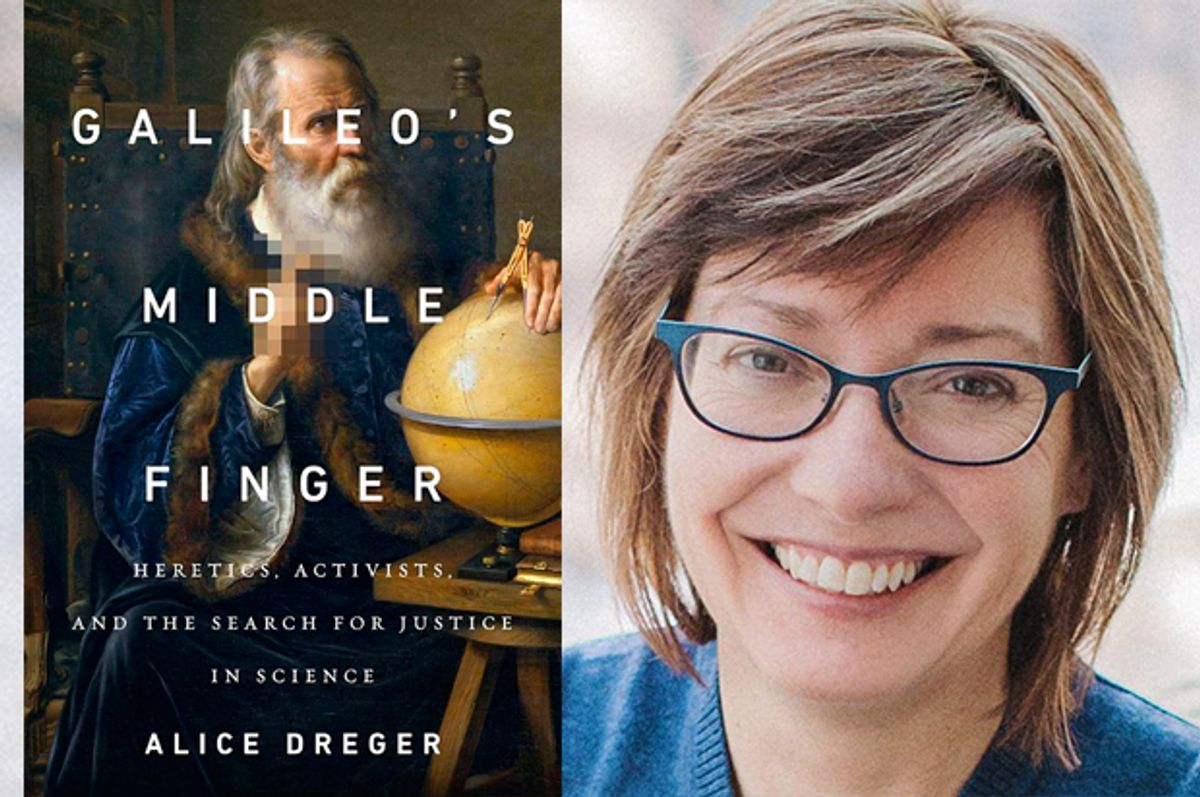

Dreger, who would become a bioethicist and historian of science as well as an advocate for sexual minorities, clearly respects her parents a great deal. The apparent contradictions in her early life might explain how, as an adult, she has been both mistaken for a militant lesbian and reviled for promulgating anti-LGBT beliefs. Or how, as a lifelong feminist, she found herself defending the macho anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon and the authors of a study often viewed as offering an evolutionary excuse for rape. Dreger’s new book, “Galileo’s Middle Finger: Heretics, Activists and the Search for Justice in Science,” is a first-person account of the seemingly endless controversies she’s dived into as she tries “to understand what happens — and to figure out what should happen — when activists and scholars find themselves in conflict over critical matters of human identity.”

For reasons unknown, Dreger’s publisher has chosen to package “Galileo’s Middle Finger” in a fashion that will mislead many into assuming it’s a history of scientific defiance from the 16th century to the present day. In fact, Galileo barely comes into it, and then only as the prototype of a certain scientific personality: the egotistical, undiplomatic sort who mulishly pursues and asserts the facts, often in a way that provokes others, but who remains fundamentally committed to the truth. (The title refers to the fact that a museum in Florence keeps the scientist’s mummified digit as a relic.) Instead, “Galileo’s Middle Finger” offers a trench-level account of several hot scientific controversies from the past 30 years, told with the page-turning verve of an exposé. Anyone who wants the first kind of book will be disappointed by it, and the many readers likely to be fascinated by what Dreger has actually written could all too easily pass it by. (So: WTF, Penguin Press?)

That would be a shame, because in addition to being highly readable, “Galileo’s Middle Finger” has an important and seldom-voiced message. “Science and social justice require each other to be healthy,” Dreger writes, “and both are critically important to human freedom.” Yet, too often, from Dreger’s perspective, ideological or politically strategic needs take priority over the evidence. People, while trying to do good, find themselves deliberately ignoring or obscuring the truth.

Dreger’s first experience of this came after she wrote her graduate thesis on how Victorian doctors treated what they called “hermaphrodites” — that is, people born with sex anomalies that make it difficult to categorize them as either male or female. Her work attracted the attention of intersex (as they now prefer to be called) activists. To Dreger's horror, she learned that modern-day doctors routinely performed surgery on such infants soon after birth to “standardize” their genitals. (The intersex activist Dreger would work with for many years had had her unusually large clitoris removed as a baby and was unable to experience orgasm.) Often the patients, and even their parents, were never informed of the truth about their own bodies. In other cases, their condition was discussed but treated as disastrous and shameful; one common, and inaccurate, piece of surgical lore held that if left as is, intersex children would inevitably commit suicide. The rights movement to which Dreger would soon devote herself urged doctors to refrain from surgical and other interventions until the patients were able to decide for themselves. On their side was ample evidence that intersex people did much better without such “treatments.”

That particular battle pitted Dreger against convention and medical inertia. Although, like all activism, the intersex-rights campaign could be draining, the author has good cause to feel proud of what she helped to accomplish within it. Her next foray proved thornier. A friend asked Dreger to look into the case of J. Michael Bailey, a psychologist specializing in human sexuality who had written a book about transsexualism that sparked the ire of some high-profile trans women.

The book, intended to offer real-life stories that illustrated the theories of another researcher, endorsed the idea that trans women have varying motivations for making the male-to-female transition. Among the transsexuals he worked with, Bailey believed he had observed at least two general types. One consisted of “effeminate” individuals who might even have done OK as gay men — provided communities (mainstream or gay) would value them just as they are — but who, given the world’s entrenched prejudices, were much happier living as straight women. The other category Bailey identified became the source of his troubles. It encompassed people who, in Dreger’s words, “looked to the outside world like typically straight men” but who inside “felt there was a powerful, almost overwhelming feminine component of their selves. Part of that sense involved finding themselves sexually aroused by the idea of being or becoming women.”

This is, to put it mildly, a controversial assertion, although both Bailey and Dreger have encountered plenty of trans women who told them that the latter category (given the ungainly name of autogynephilia) does describe their own experience. However, people seeking sex reassignment surgery have traditionally run into opposition when doctors perceived their motivations as erotic. The idea that trans identity might be, for some people, a kind of sexual orientation, flies in the face of a counterargument that has been effectively deployed by trans activists to fight social and medical prejudice: that a trans person possesses the brain of one gender trapped in the body of the other, and that a desire to make the transition has nothing to do with sexuality.

Dreger agrees that Bailey, “in his clueless privileged way … didn’t worry about his work’s political implications for sexual minorities. He worried only about what’s right scientifically,” and he’d decided, based on the trans women he’d interviewed, that this “taxonomy was right about the salience of sexual orientation to male-to-female transsexuality.” He also thought that sexual orientation was a perfectly valid reason to seek sex reassignment surgery. Dreger believes Bailey genuinely cares for and wanted to help the trans women he knew, yet she also deems several passages in his book to be insensitive and even “really obnoxious.”

Nevertheless, while she understands why some trans women object to Bailey’s book, Dreger was appalled by the campaign of character assassination levied against the psychologist by a handful of prominent trans activists. They falsely accused him of numerous violations of professional ethics, emailed his colleagues to say he was a drunk, persuaded several of his sources to turn against him by filing unsupported claims of impropriety, published misleading statements that he was under investigation (when any such inquiries were quickly abandoned as unfounded) and even appropriated school photos of his children to post with captions speculating that his daughter was “a cock-starved exhibitionist, or a paraphiliac, who just gets off on the idea of it.” When Dreger published her own debunking of these charges, she too became the subject of similar attacks.

The tragedy in this contretemps is that both sides want the best for trans women and both ended up expending huge amounts of time battling people who essentially share their own goals. In the meantime, in this sort of affair, outsiders absorb the vague impression that a targeted scholar has been tainted and may never learn the less scandalous or more complicated truth. The rest of the stories in “Galileo’s Middle Finger” involve other scientists embroiled in similarly wrongful accusations, often made for reasons unclear, or by rivals or unscrupulous and lazy journalists.

Chagnon she defends from widely publicized but trumped-up charges that he aided in the deliberate infection of an Amazonian tribe with measles. This despite the fact that he’s a figure with some non-feminist ideas about human nature, and he kept jokily introducing her to strangers as his assistant. Good scientists, she notes, often have difficult, bumptious personalities and rub others the wrong way, but that doesn’t automatically invalidate their findings. Neither should the realization that those findings, however well-supported, might be politically “dangerous.” The last third of “Galileo’s Middle Finger” is consumed by a story — about Dreger’s efforts to curtail the use of a risky experimental drug being administered to improperly informed pregnant women —t hat doesn’t really fit this pattern. Still, it’s an engrossing tale of what it’s like to try to do the right thing and then to be caught up in a tempest of controversy and recrimination with people you’d typically think of as your allies.

“Justice cannot be advanced,” Dreger writes, “by letting ‘truth’ be determined by political goals.” Dismayed by the atrophying of in-depth investigative journalism and the Internet’s viral petri dish of partisan rumor and misinformation, she found herself on a plane coming back from one investigation and musing on the role of scientists, historians and other researchers. “We scholars had to put the search for evidence before everything else,” she averred, “even when the evidence points to facts we did not want to see. The world needed that of us, to maintain — by our example, by our very existence — a world that would keep learning and questioning, that would remain free in thought, inquiry and word.”

Shares