“To cure is the voice of the past.

To prevent, the divine whisper of today.”

-- British medical journal, 1903

In the summer of 1874, a woman lay dying of tuberculosis on the top floor of a tenement building in New York City. A Methodist missionary found her there and asked if she could help. “My time is short,” said the sick woman, “but I cannot die in peace while the miserable little girl whom they call Mary Ellen is being beaten day and night by her stepmother next door.”

Mary Ellen lived in the home of Francis and Mary Connolly, though she wasn’t a blood relative of either. She was the illegitimate daughter of Mary’s late first husband, Thomas McCormick. The Methodist missionary’s name was Etta Angell Wheeler. When Wheeler entered the Connolly’s apartment, she found Mary Ellen thinly dressed, barefoot, and bruised. “She was a tiny mite,” said Wheeler, “the size of five years, though she was nine. She struggled [to wash] a frying pan about as heavy as herself. Across the table lay a brutal whip of twisted leather strands and the child’s meager arms and legs bore many marks of its use. I went away determined, with the help of kind Providence, to rescue her from her miserable life.”

It wasn’t going to be easy. First, Wheeler went to the police. “Unless you can prove that an offense has been committed,” they said, “we cannot interfere. And all you know is hearsay.” Next, Wheeler went to the administrators of several benevolent societies. Again, she was rebuffed. “If the child is legally brought to us, and is a proper subject, we will take it,” they said, “otherwise, we cannot act in this matter.” But Wheeler wasn’t giving up. “I will make one more effort to save this child,” she said. “There is one man in this city who has never turned a deaf ear to the cry of the helpless. I will go to Henry Bergh.”

In 1866, eight years before Etta Wheeler walked into his office, Henry Bergh founded the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Wheeler reasoned that, at the very least, children were part of the animal kingdom. Bergh listened to Wheeler’s story. “If there is no justice for her as a human being,” he said, “she shall at least have the rights of the stray cur on the street.” Bergh’s first act was to find justice for Mary Ellen.

The trial was a media sensation. Among the first to testify was Mary Ellen herself. “I have no recollection of ever having been kissed by anyone,” she said. “I have never been kissed by my mamma. I have never been taken on my mamma’s lap and caressed or petted. I have never dared to speak to anybody, because if I did I would get whipped.” Jacob Riis, a police reporter, described the scene. “I was in a courtroom full of men with pale stern looks,” he wrote. “I saw a child brought in, carried in a horse blanket, at the sight of which men wept aloud. I saw it laid at the feet of the judge, who turned his face away, and in the stillness of that courtroom I heard a voice raised claiming for [Mary Ellen] the protection men had denied her. The story of little Mary Ellen stirred the soul of the city and roused the conscience of the world that had forgotten. And, as I looked, I knew I was where the first chapter of children’s rights was written.”

The case of Mary Ellen dominated New York City newspapers for months. When it was over, Mary Connolly was sentenced to a year in prison; Etta Wheeler took custody of Mary Ellen; and Henry Bergh founded the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, the first organization of its kind. Its mission was clear: “To convince those who cruelly ill-treat and shamefully neglect little children that the time has passed when this can be done with impunity.”

During the next twenty years, the Society investigated more than a hundred thousand cases of suspected child abuse. As described by Charles Flato in The Saturday Evening Post, the stories were grim: “Children have been whipped, beaten, starved, drowned, smashed against walls and floors, held in ice water baths, exposed to extremes of outdoor temperatures, and burned with hot irons and steam pipes. Children have been tied and kept in upright positions for long periods. They have been systematically exposed to electric shock; forced to swallow pepper, soil, feces, urine, vinegar, alcohol, and other odious materials; buried alive; had scalding water poured over their genitals; had their limbs held in open fire; placed in roadways where automobiles would run over them; placed on roofs and fire escapes in such a manner as to fall off; bitten, knifed, and shot; and had their eyes gouged out. The reports of injuries read like the case book of a concentration camp doctor.” Within a few decades of its founding, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children had successfully prosecuted twenty-one thousand offenders and rescued more than thirty thousand children.

It was just the beginning.

In the 1930s, one medical invention proved that child abuse was far more common than anyone had realized: X-rays. Sadly, it took radiologists years to understand what they were looking at. When they did, Americans understood for the first time the magnitude of the epidemic around them—and supported legislation to prevent it.

* * *

In 1945, John Caffey, a radiologist at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University, published a paper in the American Journal of Roentgenology. Caffey described four children with “thickenings in several bones.” All four were less than three months old. “[These patients] suffered from none of the recognized conditions in which thickenings had been found previously, such as scurvy, rickets, syphilis, bacterial osteitis [bone infection], neoplastic disease [cancer], or traumatic injury.” The thickenings were a mystery. “After prolonged investigation of four patients,” wrote Caffey, “the cause remained undetermined. Traumatic injury was not observed in a single case either at home or in the hospital.”

The following year, Caffey published another paper in the same journal, reporting six more children with bone thickening. This time the thickenings, now believed to be fractures, were accompanied by subdural hematomas: collections of blood between the skull and the brain. “Some of the fractures in the long bones,” wrote Caffey, “were caused by the same traumatic forces which were presumably responsible for the subdural hematomas.” Again, parents appeared baffled. Caffey noted that these children were frequently bruised; were pale and malnourished; and always got better in the hospital and worse after they left. One child in the report returned after only a few days with five new fractures around the knee. For the first time, Caffey considered that parents might be hiding something. “In one of the cases,” he wrote, “the infant was clearly unwanted by both parents, and this raised the question of intentional ill-treatment.” Still, Caffey was hesitant to take the next step, hesitant to accuse parents of intentionally hurting their children. “The evidence was inadequate to prove or disprove this point,” he wrote, meekly.

In 1956, ten years after John Caffey had made his observations, Fred Silverman published a paper titled “The Roentgen [X-Ray] Manifestations of Unrecognized Skeletal Trauma.” Unlike Caffey, Silverman was willing to point a finger at abusive parents: “It is not often appreciated that many individuals responsible for the care of infants and children may permit trauma and be unaware of it, may recognize trauma but forget or be reluctant to admit it, or may deliberately injure the child and deny it.”

The tipping point came six years later.

In 1962, Henry Kempe published a paper titled “The Battered Child Syndrome.” This time the manuscript wasn’t published in a specialty journal for radiologists; it was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the most widely read medical journal in the world. “The battered child syndrome,” wrote Kempe, “is a frequent cause of permanent injury or death. The syndrome should be considered in any child exhibiting evidence of fracture in any bone, subdural hematoma, failure to thrive, soft tissue swellings, or skin bruising, in any child who dies suddenly, or where the degree and type of injury is at variance with the history given regarding the occurrence of the trauma.” Kempe reported 750 children with X-ray evidence of past abuse. Seventy-eight had died. One hundred fourteen had suffered permanent brain damage.

Unlike the papers of Caffey and Silverman, Kempe’s was accompanied by a press release. Within a few weeks, Time, Newsweek, Life, The Saturday Evening Post, and every major newspaper in the country were writing about child abuse. One article was titled, “Parents Who Beat Children: A Tragic Increase in Cases of Child Abuse Is Prompting a Hunt for Ways to Select Sick Adults Who Commit Such Crimes.” During the next twenty years, medical journals published more than seventeen hundred articles about child abuse. By the mid-1970s, child abuse had its own medical journal; Henry Kempe was the editor.

* * *

Kempe’s article—and the media attention that followed—opened the eyes of a nation. X-rays no longer allowed parents to deny that they’d been serially abusing their children. Congress took notice. In 1971, presidential hopeful Senator Walter Mondale (D-Minnesota) created the Senate Subcommittee on Children and Youth, a power base from which he would mobilize Congress to protect children. In 1972, the subcommittee published a book titled “Rights of Children,” setting the stage for Mondale’s seminal piece of legislation: the Child Abuse Protection and Treatment Act (CAPTA).

At 9:30 a.m. on March 26, 1973, in the wood-paneled offices of the Dirksen Senate Office Building, Walter Mondale opened the hearings. It was the first time in history that Congress had addressed the issue of child abuse. The second person to testify was the most riveting: a woman identified only as Jolly K.

Mondale: Did you abuse your child?

Jolly K: Yes, I did, to the point of almost causing death several times.

Mondale: I don’t want to embarrass you, but can you tell me what happened?

Jolly K: It was extreme serious physical abuse the two times. Once I threw a rather large kitchen knife at her and another time I strangled her because she lied to me.

Mondale: How old was the child?

Jolly K: Six-and-a-half-years old.

Mondale: And did you have repeated examples of abuse?

Jolly K: Yes. It was ongoing. It was continuous. These were not isolated instances. With parents who have this as an ongoing problem it is the difference between getting drunk on New Year’s Eve and getting drunk every day.

Jolly K. explained that she had beaten her daughter in much the same manner as she had been beaten as a child. She hadn’t, however, told her whole story; a story that included a childhood of abandonment, rape, foster homes, juvenile halls, and repeated delinquency; and a womanhood of prostitution, bad marriages, and attempted suicide. Toward the end of her testimony, Jolly K. described how she had founded Parents Anonymous, a support group for parents who abused their children. At the time of Mondale’s hearings, Parents Anonymous had helped more than four thousand families.

Although he had frequently butted heads with Richard Nixon, Mondale eventually got the legislation he wanted. “Not even Richard Nixon is in favor of child abuse!” he quipped. Mondale’s bill allocated $86 million for a center within the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (now the Department of Health and Human Services) that would compile a list of accidents involving children, publish training materials for case workers, and create a national commission to study the effectiveness of state surveillance. By the mid-1970s, all fifty states had mandatory child-abuse-reporting laws.

The impact was immediate. In 1963, public authorities had identified more than a hundred thousand cases of child abuse; by 1982, the number had climbed to 1.3 million. Advocates hailed the new legislation as a watershed event for children’s rights. But not everyone was celebrating. One group saw the legislation as a direct threat to its way of life. And it was going to do everything it could to exempt itself from public scrutiny.

* * *

In 1967, five-year-old Lisa Sheridan had a cough, fever, and difficulty breathing. Suffering from bacterial pneumonia, she could have been cured with antibiotics. Her mother, Dorothy, a Christian Scientist, chose prayer instead. At autopsy, more than a quart of pus was found in Lisa’s chest, collapsing her right lung and pushing her liver downward. The Massachusetts district attorney charged Dorothy Sheridan with involuntary manslaughter. Although Dorothy was remorseless, the child’s grandmother was appalled. “How could a mother let a sweet, dear child die of neglect,” she said, “when the laws of our land make us pick up a dog hurt in an accident and take it to the nearest veterinarian?” Dorothy Sheridan was sentenced to five years of probation. Elders in the Christian Science Church saw the trial of Dorothy Sheridan as a wake-up call; if she could be prosecuted for following the tenets of her faith, all of them were at risk. CAPTA was about to shine an unwanted light on their way of life. Something had to be done. So church authorities turned to the two men they were certain could help.

* * *

On June 17, 1972, five men broke into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate office complex in Washington, DC. A few days later, President Richard Nixon ordered his chief-of-staff, H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, to instruct the CIA to block the FBI’s investigation into the source of funding for the burglars. It didn’t work. Investigators soon traced cash and checks in the burglars’ possession to a fund dedicated to Nixon’s reelection campaign. As investigations intensified, John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s chief advisor for domestic affairs, misinformed the Attorney General that no one in Nixon’s White House had any prior knowledge of the burglary. When the dust settled, forty-eight government officials were found guilty of perjury, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice: many were sent to prison. Although Nixon was never indicted, he faced almost certain impeachment; so he resigned from office, later to be pardoned by Gerald Ford.

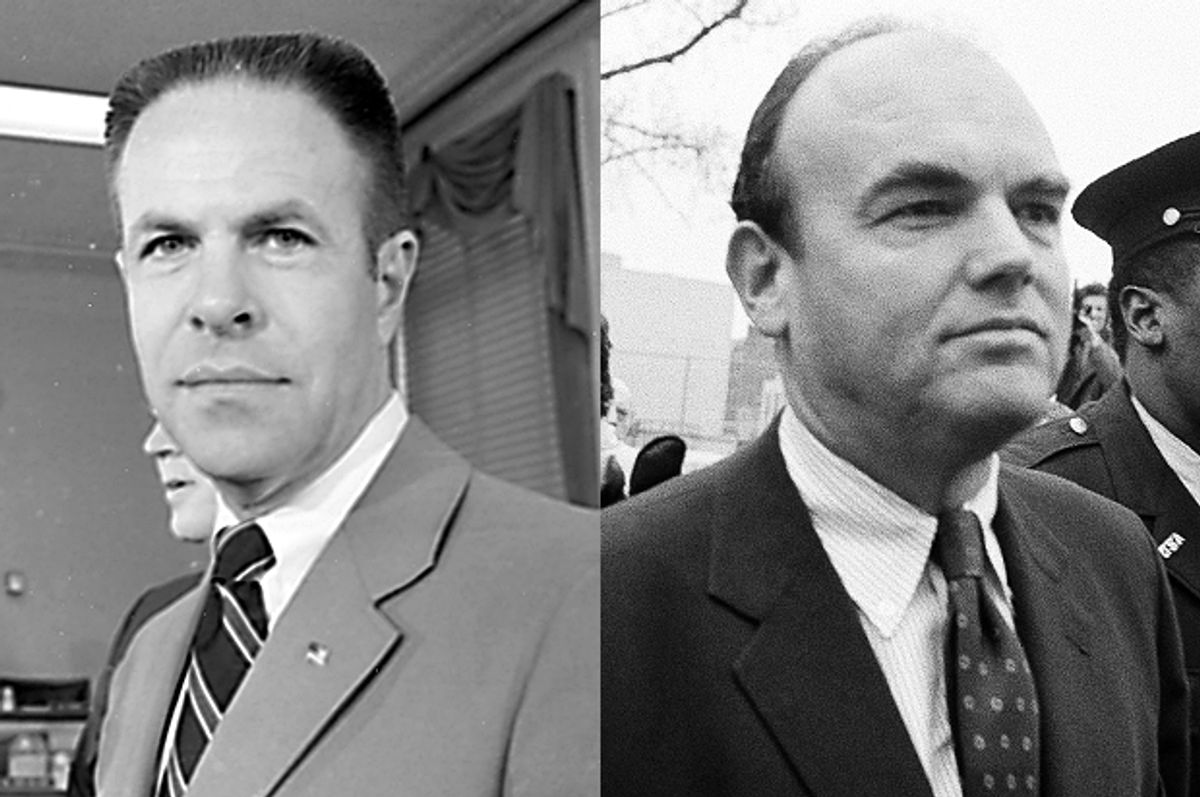

Haldeman and Ehrlichman shared several features: both were lawyers; both were powerful men in Nixon’s White House; both were of German descent (dubbed by the press “the Berlin Wall” for their fierce protection of the president); both were heavily involved in the cover-up that led to Nixon’s resignation; both were indicted, convicted, and jailed for their crimes; and both were Christian Scientists. Although the Watergate scandal consumed much of their efforts from June 1972 until their resignations on April 30, 1973, Haldeman and Ehrlichman still had enough time to insert a religious exemption into CAPTA: “No parent or guardian who in good faith is providing a child treatment solely by spiritual means—such as prayer—according to the tenets and practices of a recognized church through a duly accredited practitioner shall for that reason alone be considered to have neglected the child.”

Haldeman and Ehrlichman had tipped their hand; only Christian Scientists would refer to their prayers as treatments and to faith healers as practitioners; and only the Christian Science Church accredits its healers.

Now, if state officials didn’t abide by Haldeman and Ehrlichman’s mandate, they couldn’t receive money from Mondale’s program; within a few years, forty-nine states (the exception being Nebraska) and the District of Columbia had laws protecting religiously motivated medical neglect. By 1984, the Department of Health and Human Services, realizing the absurdity of the mandate, eliminated it. But it was too late. The damage had been done.

* * *

No case better illustrates the confusion created by CAPTA than that of Amy Hermanson.

On September 30, 1986, Amy Hermanson, the seven-year-old daughter of Christian Science parents, died of untreated diabetes. Insulin would have saved her life, but her parents chose prayer instead. Six days before Amy died, her mother, Christine, took her to a piano lesson for one of her adult students. Midway through the lesson, Amy crawled up to her mother and begged to be taken home. The student, frightened by Amy’s appearance, urged Christine to call a doctor; but she refused, saying, “She’ll be alright.” On the last day of her life, Amy lay in bed vomiting and urinating uncontrollably, attended by her parents, a Christian Science nurse, and a member of the Christian Science Committee for Publication, who forbade the nurse from calling 9-1-1. In 1989, the Hermansons were charged and convicted of felony child abuse and third-degree murder. At the time of the trial—and as a direct result of Haldeman and Ehrlichman’s additions to CAPTA—Florida had a religious exemption to civil charges for child abuse (a misdemeanor, which typically results in a fine or community service) but not for criminal charges (such as manslaughter, felony child endangerment, or murder, which typically result in imprisonment). In other words, a choice to medically neglect a child for religious reasons couldn’t be a civil offense but could be a criminal offense. This apparent contradiction was confusing for both parents and prosecutors.

In 1992, the Florida Supreme Court overturned the Hermansons’ convictions. Judges argued that religious exemption laws failed to clearly spell out the parents’ obligations: “A person of ordinary intelligence cannot be expected to understand the extent to which reliance on spiritual healing is permitted and the point at which this reliance constitutes a criminal offense. The statutes have created a trap that the legislature should address.” In other words, it shouldn’t be left to parents in Florida to figure out when they had crossed the line from a civil to a criminal act.

The problem created by Haldeman and Ehrlichman continues. As of 2013, thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia still had religious exemptions for child abuse in their civil codes, and seventeen had religious exemptions for felony crimes. In the end, these ambiguities benefit no one. Not children, who may be denied life-saving therapies. Not parents, who remain uncertain about when the line is crossed to criminal behavior. Not prosecutors, who are often unclear about what constitutes medical neglect. And not society, which is charged with protecting its youngest, most vulnerable members. The issue won’t be resolved until all fifty states eliminate religious exemptions from both civil and criminal child abuse statutes.

Excerpted from "Bad Faith: When Religious Belief Undermines Modern Medicine" by Paul A. Offit, M.D. Published by Basic Books, a member of the Perseus Books Group. Copyright 2015 by Paul A. Offit, M.D. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares