After the success of “Boyhood,” and starring in the low-budget sci-fi film “Predestination” earlier this year, actor/writer/director Ethan Hawke shifts things up a bit directing and appearing in “Seymour: An Introduction.” This charming documentary portrait affectionately showcases the wit, wisdom, and music of octogenarian New York City piano teacher Seymour Bernstein. Hawke met Bernstein at a dinner party, where they bonded over artistic crises.

As the film shows, talent can bloom when it is free. The observational scenes of Bernstein giving a master class, or a beautiful sequence in which he seeks the best Steinway in New York are enjoyable to watch even for those who have never played the piano. “Seymour: An Introduction” intimately captures Bernstein and his world, and it serves as a fine introduction to a man most viewers would never meet without this documentary.

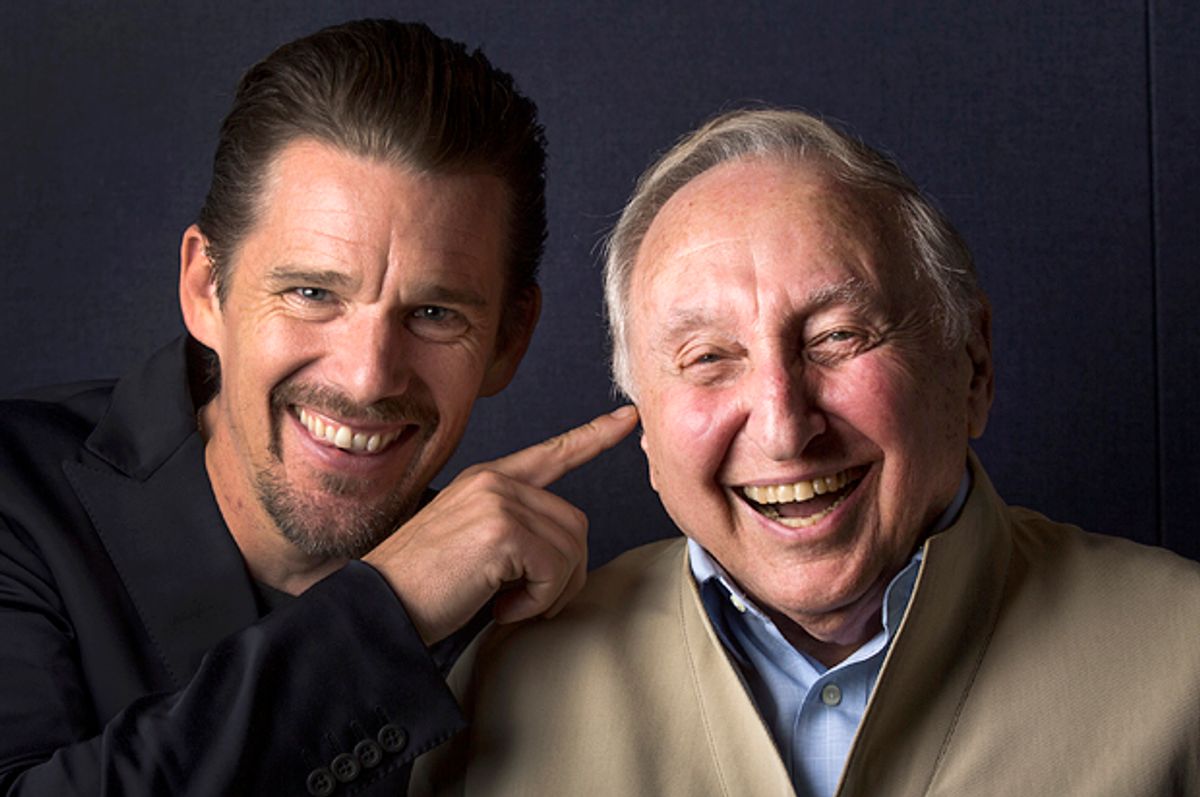

Salon spoke with Hawke about making the documentary, the folks who inspire him and what Seymour taught him about how to live.

You state in the film that Seymour helped you when you shared with him that you were having an “artistic crisis.” What guidance did he give you?

That’s the subject of the doc. Seymour is a person who has lived a full life committed to the arts, and I was struck by his happiness. So many people you meet who are older are not so happy, particularly the most “successful” ones. It’s haunting as you grow up in this profession to see so many of your mentors so unhappy. It’s frightening to wonder what you work towards. It’s better to see life not as a competition, or some kind of game you are designed to win. Life isn’t a competition and Seymour’s been very successful in figuring out how to integrate his inner life, his artistic life, and his external life. It’s hard for people to get that harmony.

Seymour says the essence of who we are resides in our talent, whatever talent there is. What drives your work: acting, writing, directing?

Mostly I [work] to keep my curiosity alive, and maintain the attitude of an amateur. I’m allergic to the idea of being a professional. I try to stay close to the pure flame in a life in the arts. It’s so much more interesting to do theater or small little weird movies or write books. The less money involved, the clearer the reason why everyone is in the room. It’s more about the expression than commodifying that expression. Cinema has been eaten by big business. That “Boyhood” survived in the corporate marketplace is remarkable.

Seymour [Bernstein, the person] is not really important. When Seymour has been in a red carpet press line, he doesn’t give glib statements. He wants to know the journalists’ names and where they are from. He embarks on a dialogue rather than gives sound bites. It’s mesmerizing to see him dismantle the process.

There is considerable talk in the film about love of doing something vs. commercial success…

Perceived success is the opposite of internal growth. The more we lose sight of that, the more we lose sight of reality. This spins in my head because with adulthood, fatherhood and responsibility, I am trying to figure out a way of maintaining idealism without being naïve. It’s more fun to stay closer to the joy of it all.

Why did you take the approach you did to telling Seymour’s story?

There’s always a gut feeling. When I read Cameron Crowe’s portraits in “Rolling Stone,” I enjoyed getting a sense of why the author was writing it. There are a lot of movies you can make about Seymour. I didn’t want the film to be about Seymour or me, but about his message — the teachings more than the man. I felt my journey as a filmmaker was relevant to the film. It’s not a biographical portrait. He was teaching me. The reason why we are making it was that we all felt there is something to learn from this guy.

There are some very lovely scenes of Seymour on stage giving workshops. His methods involve patience, and it is clear how he inspires and encourages an emotional response from his students. This is a far cry from the “Whiplash”-style music teacher. Can you discuss Seymour’s approach and what you learned about teaching artists/musicians?

What’s funny to me is that Seymour is a photonegative of the character in “Whiplash.” We all love what Seymour calls the “talent,” the American notion that you’re born with it, as opposed to craft, which is something that can be worked at. “Whiplash” promotes pain and suffering and cruelty to pull out your inner genius. Seymour cringes at that. All that stuff [talent] is already inside you and so many of us if we are in the right environment and get over our demons. You don’t need another demon to make us talents.

What demons do you battle? In the film you mentioned having stage fright.

We all have stumbling blocks and blind spots, demons and broken parts. No one comes in flawless or gets out for free. I think it’s healing when you stop pretending you don’t have it. As a teenager, I felt I should have all my shit together and be good at this, and I was often the youngest in the room. “Dead Poets Society” came out when I was 18. I wore the hat of a student; I was so worried it would be taken away from me. It was anxiety-provoking. Confidence is extremely fragile, and so much of it is a “performing” art. The older I got, the more respect I had for the profession and other people and the rare experience of it, the pressure appeared; you create it for yourself. I was nervous before an opening night in a Tom Stoppard play, and I told Stoppard that I was nervous, and he said, “You better be. You’re the tip of the spear!” Seymour teaches owning your fear and not being ashamed of it. It’s a badge of honor that comes with anxiety. People think it’s uncool to care. But it’s all right to care about things that are important to us.

Can you talk about a teacher who inspired you to perform — be it acting, writing, or even music?

There are so many people. One of the great teachers in my life was Peter Weir while making “Dead Poets Society.” I had some great English teachers in high school. And I’ve learned a lot from my friends, who are really inspiring and have different skill sets and ideas. I learned a lot about acting from Philip Seymour Hoffman.

Do you play the piano, or another instrument?

I do not play the piano, but I play the guitar. I love the piano. My dad and stepfather played it, but I was never any good at it. I have a lot of respect for it.

Seymour talks about feeling free after he quit performing and started teaching music. You have had success in acting, but have dabbled in writing and directing. Do you see shifting your career plans/goals?

I don’t think about that the way my life works. Acting and being a movie star is a young persons’ game. Life shifts you naturally out of the limelight and having a different role in whatever lake you’re swimming in. There’s a natural push. I’ve been interested in writing and directing since I was young, and I want to maintain a balance of that, with life in the theater and cinema. I try to follow my curiosity.

You tell Seymour that you want to “play life more beautifully” as you get older. Can you talk about this, and what steps you are taking to achieve this goal?

The point of that scene is that we’re all looking for this huge external shift that will change our lives, and what we need to be who we are is right in front of us. I can have the life I want depending on how I play the life in front of me. It’s simply “act better.” Work hard at what’s in front of you.

Shares