One might deem it almost shameful to publish one’s musings on the New York Times’ opinion page, the same page that continues to print, and quite shamelessly, the unapologetic scribbles of Iraq War cheerleader Thomas Friedman or the earnest yet befuddled lucubrations of useful Islamist idiot Nicholas Kristof. The first of these two columnists will probably never be called to account for the bloodshed and mayhem he has sanctioned in the Middle East. The second, I believe, means well, but by denouncing “Islamophobia” he shows he has accepted as sound a nonsense term that conflates faith and race and equates (well-founded) objections to Islam with prejudice against Muslims as people. And we should never forget that he, like Friedman, supported the Iraq War.

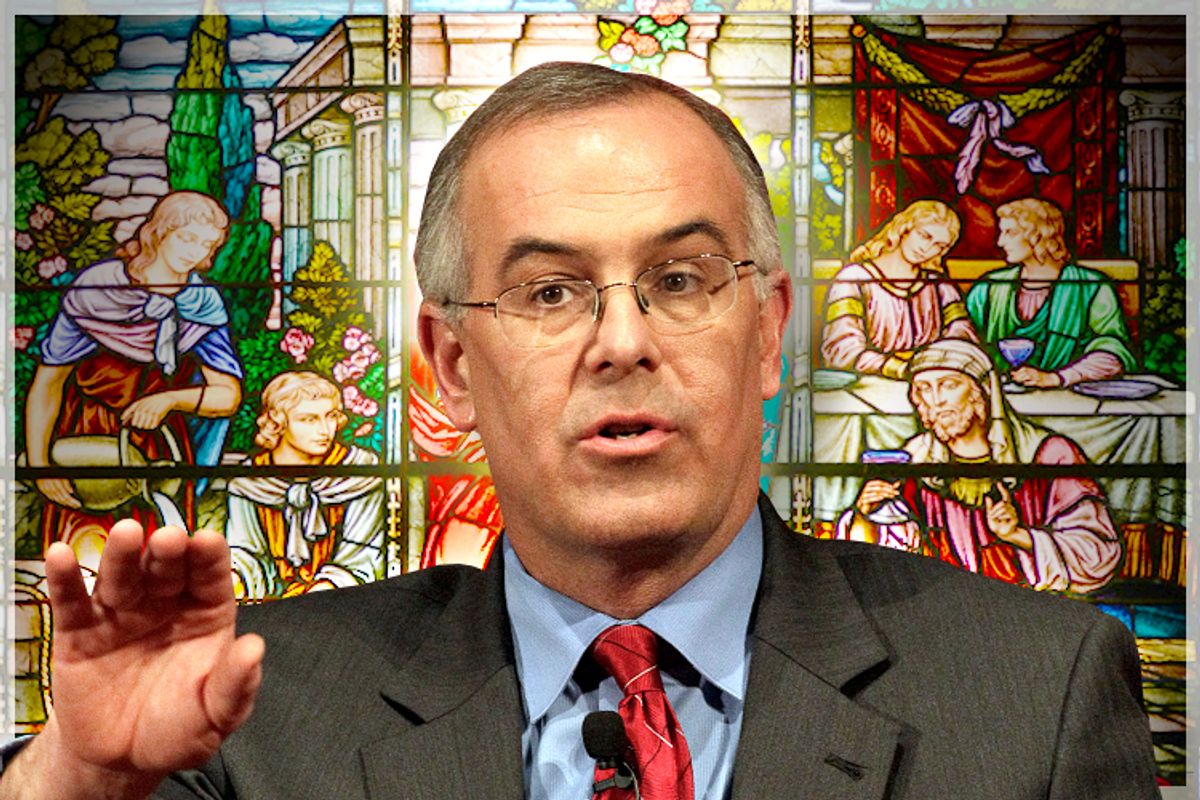

But what to make of Friedman and Kristof’s seemingly milquetoast colleague, David Brooks? No shame attaches to him, though by publishing his pro-faith columns, he validates a stupendously (if surreptitiously) baleful Weltanschauung that should long ago have disappeared from our world. Brooks, in the face of mounting evidence, has striven tirelessly to bequeath credence to the dangerous notion, ever more antiquated and morally untenable, that believing in something asserted without evidence – religion -- constitutes a virtue. That valuing faith above reason makes one a better person. That those who have shrugged off – or laughed away – the comically outlandish claims advanced by the Abrahamic creeds about our world and origins as a species are the ones with the explaining to do. Should he not be called to account?

I believe so. Moreover, Brooks’ recent Op-Ed, “Building Better Secularists,” leaves me no choice, or, better said, offers me an opportunity I cannot pass up for commentary. “Building Better Secularists” is nothing less than an anti-religion writer’s dream come true, an essay remarkable for its utter and complete susceptibility to refutation and repudiation. The title hints that Brooks intends to teach us godless folks a thing or two. The result? He succeeds only in beclowning himself by authoring a sanctimoniously gaseous tract that befits not America’s august Paper of Record, but a highbrow version of Watchtower, the Jehovah's Witnesses’ End-is-Nigh rag once handed out for free by blue-haired little old ladies in tennis shoes in front of speakeasies and liquor shops (and is now available online).

Brooks starts out by noting that those with no religious affiliation now account for a fifth of all Americans and a third of young American adults (a development that, in my view, is to be celebrated). He introduces the sociologist Phil Zuckerman and his "Living the Secular Life," a book I unfortunately have not read and so cannot comment on, but that apparently promotes the idea that secularism amounts to a “positive moral creed” based on two precepts: first, do no harm, and second, help others. Zuckerman, in Brooks’ telling, would have us believe that “secularists seem like genial, low-key people who have discarded metaphysical prejudices and are now leading peaceful and rewarding lives.” That sounds pretty good. But Brooks therein espies a critical flaw: “secular writers are so eager to make the case for their creed, they are minimizing the struggle required to live by it.”

Neither atheism nor secularism advocates a specific way of life (though I understand Zuckerman does in his book, which is fine by me). Atheism espouses no “creed,” but denotes only the absence of belief in God or gods. Secularism mostly concerns legal prohibitions – Jefferson’s “wall of separation between church and state,” for example, or France’s far more comprehensive 1905 law of laicité -- against religious folks intruding (as they have ever been wont to do) their foul fables and superstitious rituals into places where they can do great damage – the courts and schools, for example. One would hope that living free of the tyranny of an imaginary despot in the sky and his money-grubbing minions on earth would allow secularists, as Brooks says, to at least “reason their way to proper conduct,” but there is no guarantee of that.

One thing is certain, though: for the past two millennia, devotees of all the Abrahamic faiths have had more than enough opportunity not only to practice their religions and influence their communities, but to run countries and empires. The results would seem to discredit them: barbarism and murder, civil strife and war, the systematic rape of children, institutionalized obscurantism and misogyny, witch hunts, the cruelest punishments imaginable, the Crusades, the Holy Inquisition, ISIS, Boko Haram, and so on. The point is not than one or another religion is better or more correct, or more guilty or less guilty of producing “bad outcomes” such as the aforementioned, but that all are equally man-made, equally false, equally irrational, and equally capable of being used just as they have been used: as merciless ideologies of control and repression. All this immediately renders null and void the credentials of any journalist who would preach faith-tainted advice about how to live to rationalists.

Brooks proceeds to list the challenges he demands be met if atheists are to prosper. Each of these challenges he presents in contradistinction to its religious equivalent.

Let’s take them one by one.

1. “Religions come equipped with covenantal rituals that bind people together, sacred practices that are beyond individual choice. Secular people have to choose their own communities and come up with their own practices to make them meaningful.”

Since Brooks is Jewish, presumably the circumcision (of baby boys) is the primary “covenantal ritual” he has in mind. Of course there are other rites: acting out cannibalistic fantasies in the Eucharist, eating wafers for flesh and drinking wine for blood; spouting gibberish in tongues; gyrating on the floor; genuflecting toward Mecca, and so on. (One other particularly savage ritual comes to mind, and it is truly “beyond individual choice”: female genital mutilation, usually inflicted on its victims – currently some 125 million women in at least 29 countries -- with license from the Islamic canon.) No atheist is obligated to concoct practices similar to the sacraments Brooks considers necessary for “meaning,” or, obviously, to the ghoulish outrages other faith-deranged folk make a habit of casually visiting on their fellows. Disbelief in God obliges me to search for no “community” at all. “Meaning” I can discover on my own, without recourse to fallacious dogmas or conferring with the deluded souls who adhere to them.

2. “Secular individuals have to build their own Sabbaths. Religious people are commanded to drop worldly concerns. Secular people have to create their own set times for when to pull back and reflect on spiritual matters.”

I, a lifelong atheist, need a Sabbath? This is news to me. I associate Sabbaths with the punishment – the death penalty – that Leviticus and Deuteronomy mete out to the violators thereof. Scheduling time to “reflect on spiritual matters” generally poses no problem for anyone who can, let’s say, read a clock. Children usually manage this feat by age 7 or so. If Brooks needs to rely on a magic book’s calendar to help him find time to “pull back,” that’s not my problem.

3. “Secular people have to fashion their own moral motivation. It’s not enough to want to be a decent person. You have to be powerfully motivated to behave well. Religious people are motivated by their love for God and their fervent desire to please Him. Secularists have to come up with their own powerful drive that will compel sacrifice and service.”

I can’t see why Brooks believes it takes the dubious incentive of a pat on the head from a fictitious heavenly boss to keep us from ceding to felonious urges or nasty impulses. I require no such inducement, let alone must I be “powerfully motivated” to “behave well,” nor do other decent people. I do know that a “fervent desire” to please God sometimes drives people to commit vile crimes, including, for example, the murder of satirical cartoonists in Paris. Oxfam, Doctors Without Borders, Unicef and the Peace Corps – secular organizations all – minister to the poor and needy, without invoking the divisive hokus pokus of faith, the silly abracadabra of prayer, the inanities of the Abrahamic texts. Moreover, it’s pretty well established that evolution naturally tends to foster a core morality; even Darwin saw this. This last fact alone slips the keen-edged bodkin of reason between the ribs of fabulists who preach their “holy” books as correctives to improper conduct. We (mostly) look out for one another because otherwise we, as a species, would not have survived.

Brooks then (unconvincingly) professes to worry about us atheists, and laments that “an age of mass secularization is an age in which millions of people have put unprecedented moral burdens upon themselves. People who don’t know how to take up these burdens don’t turn bad, but they drift. They suffer from a loss of meaning and an unconscious boredom with their own lives.”

I suppose I’ve been too busy “drifting” and reeling under the weight of all the “unprecedented moral burdens” I’ve saddled myself with by disbelieving in God to notice my “loss of meaning” and “unconscious boredom.” In fact, I rather enjoy the freedom to determine my life’s course without adherence to obsolete strictures coming down to us from ancient eras, and I know many other atheists who feel the same way. We find emancipation in the truth, announced as far back as Epicurus’ time (and thus hardly “unprecedented”), that death will not pain us, since once it happens, we shall be no more.

And one other point almost too obvious to make: imagine what would happen if “mass secularization” were to break out in ISIS territory? How bad would that be?

Brooks goes on to dismiss the (sadly) bygone Enlightenment and what he finds to be erroneous notions about how man can “reason his way to virtue.” Says he, as if revealing to us hitherto unspoken truths, “We are not really rational animals; emotions play a central role in decision-making, the vast majority of thought is unconscious, and our minds are riddled with biases. We are not really autonomous; our actions are powerfully shaped by others in ways we are not even aware of.”

Such banal truisms would surprise no semi-literate individual in our post-Freudian, post-Jungian, post-Skinnerian world.

Once we nonbelievers have made peace with our irrationality, Brooks concludes, we need to get cracking on the inspirational front. “Secularism has to do for nonbelievers what religion does for believers — arouse the higher emotions, exalt the passions in pursuit of moral action.” We should, he says, emulate those good Christians who put “agape at the center of life.”

There’s nothing wrong with agape, or love. We do not require belief in God or gods to feel it. But religious authorities have aroused “emotions” and “passions” in pursuit of some rather notorious “moral actions” that had little to do with love. To wit: recall the frocked sadistic monsters of the centuries-long Inquisition at work crushing the skulls of, and ripping the breasts off, (innocent) parishioners accused of ruining the village crops, administering the strappado to the feet of “heretics” and shoving expandable metallic “pears” into the vaginas of “witches.”

Atrocities from times past, these, to be sure. But they attest to the grisly iniquities to which faith has led and still leads. That Brooks can seriously present religion as a force for good today has everything to do with the Enlightenment he disses, with our hard-won secular governance. That is, with religion’s having lost the power struggle, at least in the West. When “men of the cloth” ruled us, they did not hesitate to apply the thumbscrews, and, no doubt, “exalted” as they did so.

Brooks then contends that we secularists need to find an atheistic equivalent of Judaism, the “sacred bonds and chosenness” of which “make the heart strings vibrate.” Such tunes certainly sound less than melodious to the “unchosen” Palestinians. Nor did they please the people of Heshbon, who, says Deuteronomy 3:6, down to the last man, woman and child, suffered destruction at the hands of the Israelites. Also finding such music less than enjoyable were the Canaanites, the Amelikites, the Philistines and the thousand poor souls Samson bludgeoned to death wielding nothing more lethal than the “jawbone of an ass” – something TSA officials might want to add to their list of prohibited-for-carry-on items.

Brooks closes with what, to him, seems like a rousing call for “enchanted secularism” “that puts emotional relations first and autonomy second . . . . responsive to the spiritual urge in each of us, the drive for purity, self-transcendence and sanctification.”

Finespun malarkey, this. Autonomy begins with freeing oneself from faith-based dogma and its self-sainted representatives, and must take precedence over “emotional relations,” over any pleasant sensations flowing from that dogma. We may indulge our “spiritual urges” in any number of ways – meditation and yoga, lying in the arms of our loved ones, long walks in the woods, and gazing into the night sky among them. Drives for “purity” should arouse nothing but suspicion; they often lead to a preoccupation with the “unclean,” to campaigns to extirpate the “impure,” with women, sexual minorities and freethinkers suffering as a result.

And “sanctification” reeks of put-on respect for mundane relics and “righteous” fraudsters who end up abusing the authority the misguided invest in them to, say, abuse women and embezzle funds. Clearly, atheists are capable of such crimes too. But the example provided by the Vatican alone, an obscenely wealthy institution that has crippled so many vulnerable members of its “flock,” offers us one conclusion: we must shun sanctification of people or institutions.

Secularists, in closing, are perfectly capable of finding their way without advice from religious folk. Brooks’ hazy happy talk about God ill accords with religion’s gruesome past and violent present; and, appearing as it does in a major newspaper, grants a sheen of respectability to an outdated phenomenon we would all be better off ditching.

All New York Times columnists should consider that, or they risk spreading not light, but dark.

Shares