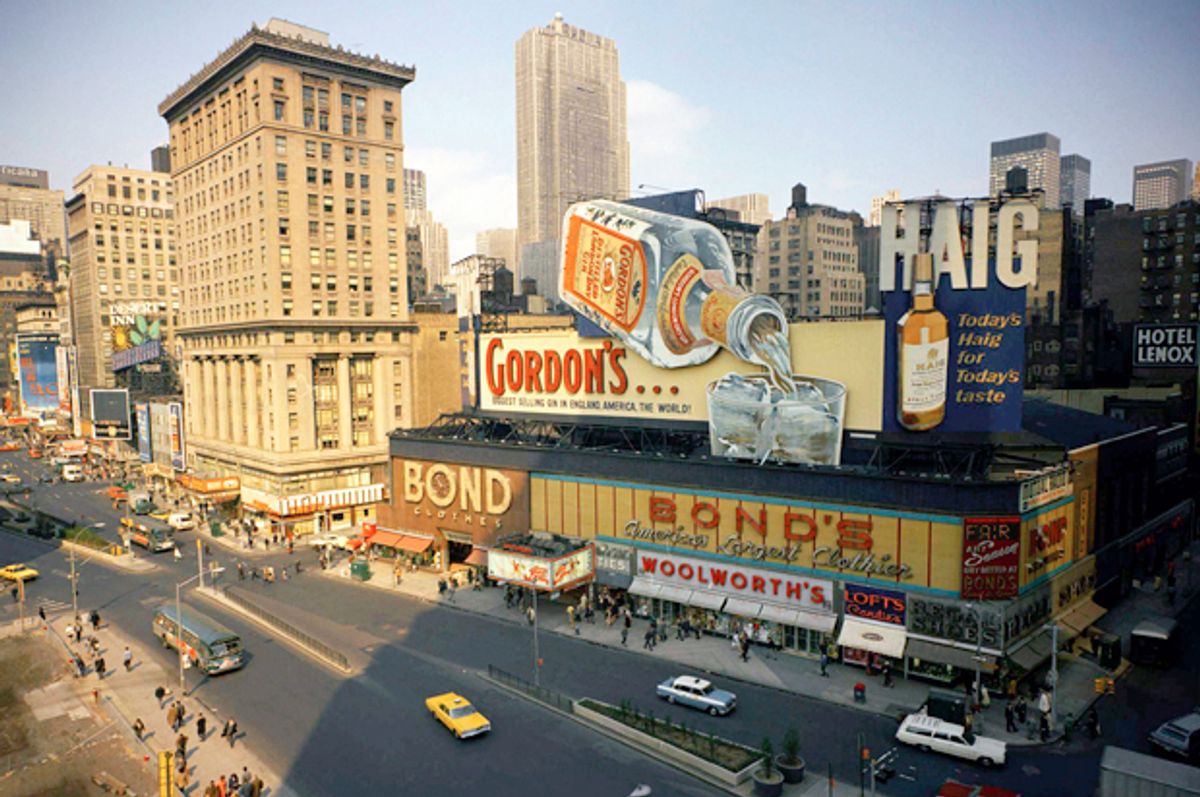

He is New York’s own “Giver.” Burdened with invisible history, haunted by ghosts of pierogis and vinyl records, fighting against a “blankness” that he sees in both the storefronts and faces of the East Village, Jeremiah Moss has for seven tumultuous years chronicled changes in the Manhattan streetscape.

Hyperbolic and combative, tireless and passionate, Moss (the name is a pseudonym) has run the Vanishing New York blog with a keen eye for New York’s past. When Michael Bloomberg, one of his favorite targets, left office in 2013, Moss concluded that New York had lost, at a minimum, 6,926 years of history in the erosion of small businesses during his three terms. “Perusing the list” of shuttered stores, wrote Kristin Iversen, "was not unlike looking through a high school yearbook, only finding out that practically everyone had died."

But devotion to the past, as Susan Sontag observed, is “one of the more disastrous forms of unrequited love.” These days, Moss is looking toward old friends who are still alive — shifting his business from headstones to healthcare, if you will.

In December, after a hugely popular but unsuccessful movement to save Cafe Edison, the theater district diner with high ceilings and low prices, Moss started a campaign called “Save NYC” to protect the city’s commercial heritage.

In Manhattan, retail rents are up 40 percent since 2005. In Lower Manhattan, the average retail rent is now $265 per square foot — up from $92 in 2005. That rent hike has concurred with a spike in chain stores: According to the Center for an Urban Future, Manhattan now has 2,807 chain stores, a 10 percent increase since 2009. The citywide total has risen 18 percent in that time. And while no one but Moss tracks the closing of places like Pearl Paint and Avignone, there’s a widespread sense that the city is losing older stores at a rapid clip.

From a Facebook page, Moss has now developed a website, nurtured a hashtag (if such a thing can be said) -- #SaveNYC -- and assembled a policy agenda. He’s advertised his plans in the New York Daily News and been featured on the local TV news and CNBC. Soon, he hopes to have “Save NYC” signs in the storefronts of mom ’n’ pops across the city.

The political objectives: Fine landlords who leave commercial spaces vacant, end tax breaks for multinationals, zone out chain stores, start a “cultural landmarks” program, and pass the “Small Business Jobs Survival Act,” a negotiating guideline for commercial tenants and landlords.

Café Edison, where the playwright August Wilson once wrote his dialogue on napkins, eventually succumbed to the landlord’s desire to open a high-end restaurant in the space. But the movement to save it was instructive.

First, the army of supporters that invaded the dining room for lunch every few weeks provided evidence that New Yorkers cared. “People actually showed up,” Moss said on Friday. “It was the first thing I’ve been involved with where people really showed up in large numbers, and politicians showed up.” Second, it demonstrated that widespread popular support (and even a message from Bill de Blasio) couldn’t stand up to the simple financial incentives of commercial landlording.

"I think people are noticing more and more what’s happening to the city,” Moss observed. “But they don’t seem to be aware that something can be done about it.”

New York is at an immediate disadvantage in this regard: Most templates for preserving old businesses in high-cost cities come from Europe. There’s less respect for landlords and more agreement on what constitutes culture worthy of preservation. That’s how Paris keeps its bookstores; that’s also why more than 300 English pubs are now classified as “community assets.”

There are fewer examples in the United States. San Francisco, which Moss holds up as a paragon, has an application process for chains that has kept local hardware stores and groceries in business. The city is currently considering a “legacy business” law that would offer 30-year-old businesses incentives and tax breaks, another idea Moss would like to bring to New York.

Moss is in some way an unlikely candidate to lead the charge. For one thing, his real identity is unknown. For another, his persona at Vanishing New York has been a defender of the old, but not always the independent.

In fact, Moss is openly contemptuous of many of the city’s newer stores and its younger residents. Bobos, with their twee and pricey retail habitats, are often a target. Don’t get him started on smartphones.

Save NYC will have to be more inclusive, and he knows it. “Save NYC is not about old businesses and it’s not about nostalgia,” he told me. “I want to move beyond that. It’s really about having New York be full of businesses that are small and local.”

That means gastropubs, juice bars and yoga studios joining forces with butchers, bodegas and dive bars. When I suggested a parallel to the locavore movement, a kind of consumer consciousness aimed at shopping at local drugstores, groceries and so on, I could almost hear Moss wince through the phone.

I think he may have more in common with the kids in the East Village than he knows.

Shares