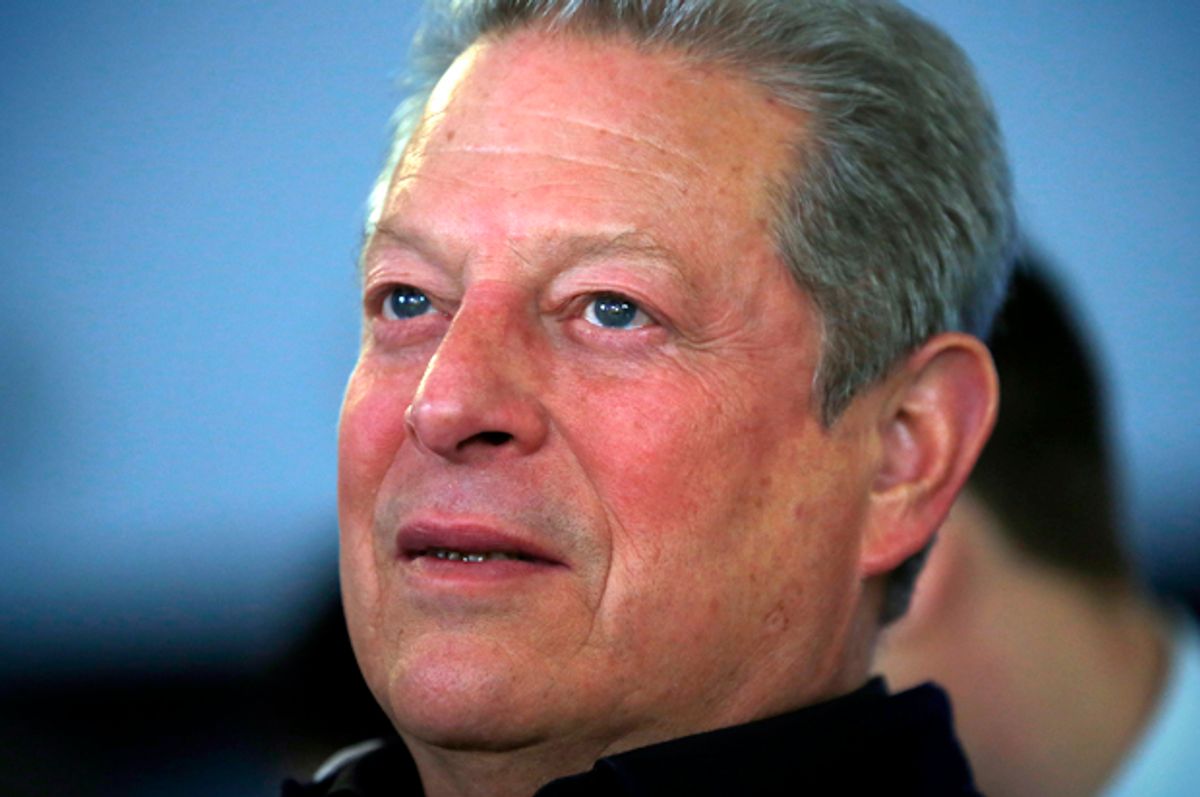

The notion of an Al Gore presidency seemed to fade with his decision not to seek the Democratic nomination in 2008, a decision the former vice president made even though his climate activism and fierce denunciations of the Bush administration had generated a groundswell of support.

But early stumbles by Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton have put Gore back on the chattering class's mind, with some pundits speculating that Clinton's shortcomings could prompt him to plot a presidential comeback. Ezra Klein is the latest to float a third Gore campaign, writing today that the ex-veep "offers a genuinely different view of what the Democratic Party — and, by extension, American politics — should be about."

Let's get this much out of the way: If Gore really wants to run for president in 2016, he should. As a former congressman, senator, and vice president -- then a globe-trotting activist, businessman, and Oscar winner -- Gore boasts a wide-ranging resume unmatched by any other potential candidate. But there's no indication that Gore wants to run, and the case for him to make the race is a remarkably weak one.

Take Klein's piece. Though he maintains that Gore "need not be a single-issue candidate," Klein sees Gore's impassioned climate advocacy as the primary reason he should come out of political retirement. Whereas economic inequality is a "serious problem," he writes, the climate crisis is an existential one -- and Gore is uniquely positioned to address it:

When it comes to climate change, there's no one in the Democratic Party — or any other political party — with Gore's combination of credibility and commitment. Bill McKibben, founder of the climate action group 350.org, calls Gore's work on the issue "the most successful second act of any political life in U.S. history." Perhaps that's hyperbole, but it speaks to the regard Gore is held in by climate activists. Though he's been out of office for 15 years, he's never left the climate fight. Gore has proven himself the opposite of those politicians who love the game more than they care about the issues.

Moreover, in an era where very little moves through Congress, climate change is an issue where the president has real unilateral authority. The Environmental Protection Agency has the power to aggressively regulate greenhouse gas emissions — a process the Obama administration has begun, but the next president will need to continue. Much of the crucial work on climate change requires coming to agreements with India and China — and that, too, is an arena where the president can act even if Congress is paralyzed.

Note that Klein doesn't lay out what unilateral actions Gore would take that any other Democratic president wouldn't. (Indeed, as the Obama administration's EPA regulations and landmark climate agreement with China attest, a Gore presidency is not a prerequisite to robust executive action.) Moreover, Klein gives short shrift to one of the more glaring drawbacks of a Gore redux. Though Klein concedes that Gore could "polarize [climate change] yet further," he doesn't flesh out the implications of once again making Gore the face of global warming -- implications that should give one pause.

You may remember that during the rollout of his documentary "An Inconvenient Truth," and for years thereafter, climate skeptics have proven all too keen to pounce on Gore's hypocrisies -- his sky-high utility bills, his fondness for private air travel, and so on -- as if his own bad habits somehow debunked climate science; Sen. Mark Kirk (R-IL) even cited Gore's marital troubles in explaining his about-face on the issue. It's all patently ridiculous, but even the patently ridiculous helps shape our political discourse. So those of us who acknowledge climate change as an existential threat must also own up to the fact that the anti-science crowd relishes the idea of Gore as their foil. Laudable as Gore's climate work has been, his political reemergence would risk debasing the climate debate at least as much as it would offer hope for moving that debate forward.

Central to Klein's thesis, of course, is the idea that climate change, rather than inequality, is the crucial challenge confronting the country, and the Democratic Party. I don't quibble with the plain fact that global warming imperils the survival of the planet as we know it, but in dismissing the centrality of inequality, Klein commits a few errors. He frames the differences between Clinton and progressive populist Elizabeth Warren thusly:

[T]he differences between Warren and Clinton are less profound than they appear. Warren goes a bit further than Clinton does, both in rhetoric and policy, but her agenda is smaller and more traditional than she makes it sound: tightening financial regulation, redistributing a little more, tying up some loose ends in the social safety net. Given the near-certainty of a Republican House, there is little reason to believe there would be much difference between a Warren presidency and a Clinton one.

I'll grant Klein that a President Warren probably wouldn't enjoy a Congress receptive to her most progressive proposals, but the sheer terror Warren strikes in the hearts of Wall Streeters -- contrasted with the financial industry's affinity for Clinton -- underscores that their differences are more profound than Klein lets on. What's more, while Klein pooh-poohs congressional intransigence on climate by highlighting the power of the executive, he strangely ignores the likelihood that Warren (or someone like her) would appoint far more vigorous regulators and Cabinet officials than Clinton would. (Does anyone honestly believe that Clinton had any problem with Antonio Weiss' Treasury nomination? Or that she wouldn't stock her administration with Wall Street alumni?) Warren has been clear and forthcoming on these issues, whereas Gore -- who's made millions working for a private equity fund -- has not.

Perhaps that's why there's been an outpouring of institutional and popular support for a Warren campaign, despite the senator's insistence that she's not interested. Meanwhile, there's no serious effort underway to draft Gore into the race, and it's unclear that his flirtation with another run would spark much enthusiasm.

Klein points out that Gore enjoys an extensive list of contacts in politics and business -- potentially setting him up to compete well against Clinton's financial juggernaut -- but where are the people stepping forward to say that they'll bankroll a Gore candidacy? It's depressing that we even have to ask the question in this money-saturated political culture, but so it goes. Warren at least has wealthy liberals like Guy Saperstein and a few Hollywood types pushing for her to run. Gore would surely have his own prominent boosters if he entered the race, but it's telling that wealthy donors dissatisfied with Clinton have largely turned to contenders besides the former vice president.

To be sure, Klein readily admits that Gore would face daunting odds if he mounted a campaign. But a presidential bid offers a "platform," he argues, and the 66-year-old Gore is unlikely to find a similar opportunity after 2016. If Gore were a relative unknown or a political newcomer, this analysis would be more persuasive. Gore possesses a platform now, and there's no good reason to risk it with a fool's-errand presidential campaign.

Shares