I once asked the spiritual writer and psychotherapist Thomas Moore why the people who set themselves up as arbiters of personal morals – the Ted Haggards, Laura Schlessingers, Jimmy Bakkers, Jimmy Swaggarts – always turn out to be one ticking kitchen timer away from a sex scandal.

“Because,” says Moore, “they’ve already acknowledged how powerful this material is for them.”

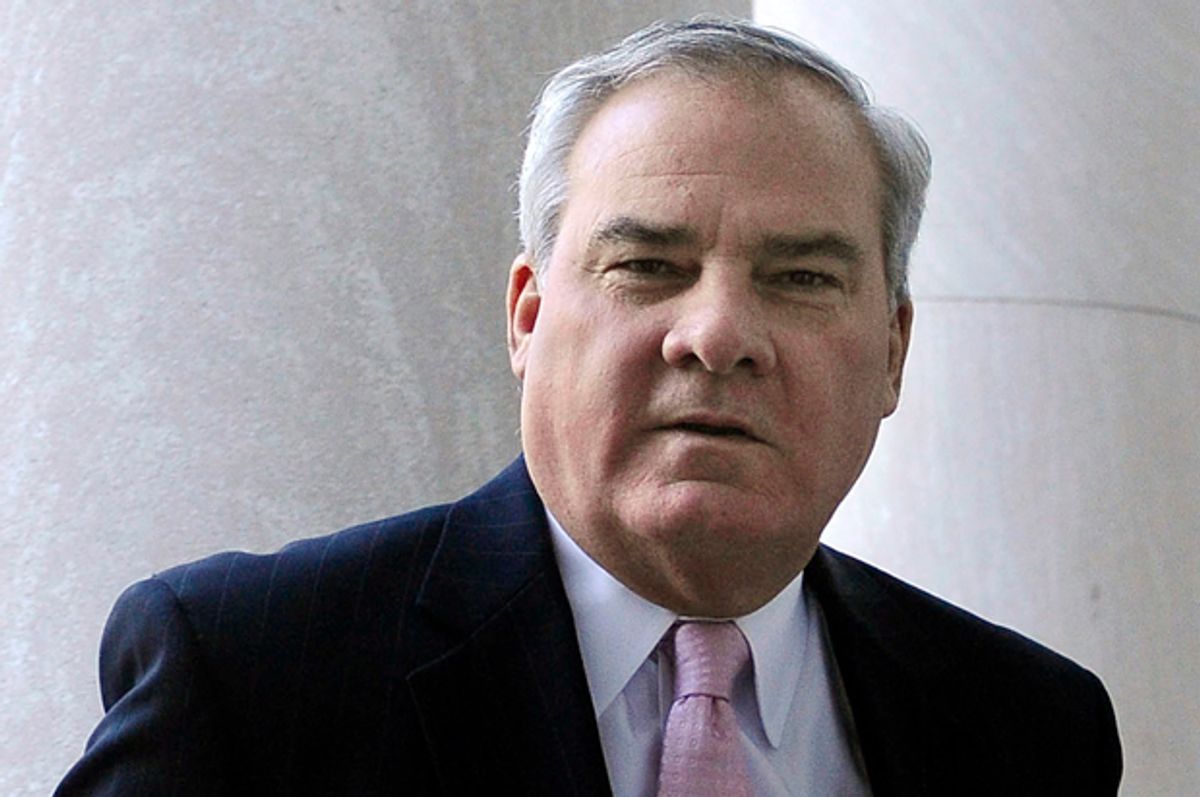

Great line. I thought of it Wednesday as former Gov. John G. Rowland was sentenced for the second time on corruption charges. No Connecticut politician, in my 35 years covering the state, made such a show of being tough on crime and fond of prisons crammed to capacity with people serving long sentences. We’re starting to see why he found the subject so compelling.

Also known as federal inmate No. 15623-014, Rowland governed the state for 10 years and then resigned with the Furies of impeachment snapping at his heels. Rowland went to prison on April Fool’s Day 2005 and stayed there less than a year. The prank was on the people, not the perp. The scope of Rowland’s corruption was mammoth, but he drew a federal judge famously lenient with white-collar criminals.

This time he was not so lucky. Federal Judge Janet Arterton has been historically tough on political corruption. She gave him 30 months of three hots and a cot (in Otisville, N.Y., the cushy prison Bernie Madoff unsuccessfully begged for, a far cry from Wallens Ridge, the deadly Virginia supermax craphole to which Rowland enjoyed farming out prisoners). With time off for good behavior Rowland could be out in 25.5 months, but, as one of his toughest critics pointed out this week, Rowland is on record as opposing good time credits and early release. For everybody else.

There are two reasons to tell the story of Rowland to the world outside Connecticut. The first is that he might be the most chronically and irredeemably sleazy American politician since the Nixon era. The second is that he so perfectly illustrates the way political corruption in America is regarded as vaudeville rather than tragedy. Rowland is headed back to prison partly because he treated post-Watergate clean government laws as a big joke and partly because almost everybody else did too.

There were signs, early in the man’s career, that he was headed for trouble. As a young congressman, he bounced 108 checks (worth about $20,000) in the House banking scandal. Then came the questions about whether Rowland had violated the generously murky laws against lobbying (on behalf of Connecticut defense contractors), post-Congress. Rowland’s next scandal came when the police chief of Middlebury, Conn., quashed incident reports relating to a 911 call from the home of Rowland’s ex-wife. The two had been arguing, and the cops were called. We never learned more, even after protracted efforts, first before the state FOI commission and later in court. Cute detail: Rowland was aided in keeping the case report sealed by two judges: the one in his divorce case and the one who heard the appeal of the FOI decision. Both were promoted to prominent jobs (including a seat on the state Supreme Court) during the Rowland years, and the two of them fell in love and got married.

Rowland was sworn in as governor in 1995. There was, almost from the start, a steady drumbeat of minor malfeasance. Rowland was hit with ethics fines, first in 1997 for accepting free tickets to rock concerts on six occasions. Cute detail: one of the concerts was a Michael Bolton gig. Seventeen years later, in 2014, the man who recorded “Said I Loved You…But I Lied” wrote a letter to Judge Arterton urging leniency for Rowland. The next ethics fine, in 2003, was for free or discounted vacations from a contractor doing a lot of business with the state. By that time, a federal grand jury was looking at Rowland in a bigger way.

There were other hints that something was wrong. A fishy deal with Enron in which the state lost $220 million. Constant drumbeats of wrongdoing in state agencies, especially the Department of Environmental Protection, where Rowland fixers could make the problems of the politically wired go away. Let me draw your attention to the case of Anne Rapkin, an ethically scrupulous lawyer in that agency who tried standing up to the Rowland bullies and was harassed and demoted for her troubles. Rapkin sued and settled, but part of the deal was a gag order. Think about that: taxpayer money was used to pay a whistleblower not to say what she knew. Keep an eye out for that in your own state. Anti-disparagement clauses for ex-government employees should be illegal 99 percent of the time. That’s information we own.

From 2003 to 2004, the Rowland mythology slowly imploded before the eyes of the voters who had elected him three straight times. Caught in a triple-pincer movement by the Department of Justice, the press and a House select committee on impeachment taking sworn testimony, Rowland was revealed as a man who lived under a waterfall of cash and gifts from people who owed him their jobs or wanted to do business with the state. Cigars, champagne, a trip to Vegas on a charter jet, and always money, kicked and pushed to him in ingenious ways. One developer arranged to rent Rowland’s Washington, D.C., condo for a rate way above market and then purchase for an exorbitant price it through a straw buyer. (Cute detail: the straw man was Wayne Pratt, who went on to some acclaim as an appraiser on PBS’s “Antiques Road Show” and was embroiled with the FBI in a colorful battle over an apparently stolen original copy of the Bill of Rights which he had purchased in collusion with the same developer.)

The spotlight locked on a lake cottage the Rowland owned in Litchfield, where lavish improvements and additions( including a notorious hot tub) had been paid for or donated by Rowland appointees or state contractors. Rowland went before the press and told a bald-faced lie: that he’d paid for it all through a home equity loan. No such loan existed. That was the beginning of the end. Cute detail: The Rowlands tried the common tactic of producing a batch of checks written years after the renovations to “prove” they had paid. Patricia Rowland turned out to have a fondness for Looney Tunes-themed checks. I remember one in particular that showed Bugs Bunny teeing up Elmer Fudd’s head. Second cute detail: with the hounds circling the Rowlands at the end of 2003, the couple made a garish public appearance at which the First Lady read a parody version of “A Visit from St. Nicholas” that openly taunted the press for covering their troubles, thus cementing her status as the Lady Macbeth of the Nutmeg State.

That poem distracted people from another startling moment in which Rowland quoted C.S. Lewis: “In adversity, God shouts to us.” He added, “Needless to say, I am hearing him loud and clear.” It was the ramping up of a new religious persona for Rowland. In the months ahead, he would court and receive the support of conservative clerics, especially Will Marotti, a pastor loosely tied to Ted Haggard’s New Life movement. Marotti brought a couple dozen ministers to the Capitol to pray for forgiveness for Rowland.

It didn’t work.

Rowland resigned from office the day after his attempt to quash House subpoenas for him and his wife failed before the Supreme Court. He then pleaded guilty to a criminal conspiracy in which tens of millions in state contracts were awarded to contractors who took care of him. One of the contracts was for a juvenile prison so badly constructed by Rowland cronies under a no-bid deal that his successor suggested closing it.

When Rowland emerged from prison he embarked on a life of menial work at low wage jobs and stayed as far from the public sector as possible. No, I’m just kidding. He was handed a six-figure job as economic development director for the city of Waterbury, his home town. In 2010, he landed a drive time slot on a conservative talk station. His partner was – wait for it – Pastor Will Marotti and the program was called State and Church. By the time the feds caught up with him, he was pulling down $420,000 a year.

OK, cards on the table time. I have been a prominent critic of Rowland in print and on the airwaves since about 1992. For 16 years I worked at that radio station, WTIC-AM, as their house liberal. They dumped me in 2008 and went all-conservative. Less than two years later, they hired Rowland for my old drive time slot.

Around the same time, Rowland tried to secure work as a campaign consultant to Republican congressional candidates. To one, he proposed being paid surreptitiously though the candidate’s animal shelter, thus dodging any publicity about having a felon on the campaign staff. That guy turned Rowland down, but two years later he worked out a similar deal with a congressional aspirant named Lisa Wilson-Foley. He was paid through the nursing home company of her husband Brian. The couple is wealthy but, prior to her sudden interest in politics, not all that public-spirited. After 9/11, Wilson-Foley was talking to a society reporters at a gala and cheerfully mentioned that she and Brian now had an escape plan involving them, their kids and their private plane. Buh-bye, people dying of radiation sickness! Cute detail: In perhaps the preeminent white privilege moment of 2014, while awaiting sentencing in the Rowland case, Wilson-Foley was granted permission by the court to accompany her daughter to summer camp. In France.

Wilson-Foley got a lot from the man she was secretly paying. He not only advised her campaign but also closely coordinated its activities with what went out over the airwaves on his talk show. In a recent filing, federal prosecutors said State and Church “became an organ” of the campaign. In particular, Rowland used the show to rip into Andrew Roraback, the Republican who eventually beat Wilson-Foley for the nomination. In his brashest move, Rowland, while excoriating Roraback on the air for his soft stance on the death penalty, texted the campaign during a break, got Roraback’s cell phone number, and then gave it out in the air, urging listeners to call the candidate and give him what for. That story was verified at trial, under oath, by a campaign staffer, thus throwing a shadow on a bizarre hand-scrawled note from Rowland to the Federal Elections Commission in which he denied having done such a thing.

A jury quickly convicted Rowland on all seven felony counts. And that, weary reader, brings us to Wednesday.

What are the lessons? The first has to do with how we enable corruption. Rowland pranced through two decades of chicanery because people tended to laugh off his misdeeds. Even after his first prison stretch, Rowland was greeted at public functions like a conquering hero. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve been told by members of the public that Rowland’s offenses were trivial. On his radio show, Rowland was addressed by callers, confederates and guests as “Gov.” He presented himself a crusader for good government and never mentioned his sordid past. As I have written elsewhere, it was as if Captain Hook had a talk show where he never acknowledged having been a pirate. After a summer of blistering trial testimony about the collusion between Rowland and Chris Healy, a former GOP state chairman and unindicted co-conspirator in the Wilson-Foley case, the state senate Republicans hired Healy as their new mouthpiece.

A second lesson: Rowland is a great reminder of the hazard posed by making “cranes in the air” a benchmark for successful governing. It’s treated as received wisdom that when there’s a lot of new construction around, government is doing a good job. Reviewing Rowland’s story, I was freshly reminded of his insatiable need for bricks, mortar and blacktop work he could steer to his cronies. His success model was built on having state-funded work he could steer to lawyers, engineers, contractors, developers and big companies. Some were bribing him. Others were simply paying to play by making legal campaign donations. The result was a stew of feverish ground-breaking, a lot of it ill-advised. People forget that the disastrous Fort Trumbull project – which led to the famous Kelo decision on eminent domain – was cooked up in one nodule of the Rowland honeycomb.

The deepest lesson is one I almost can’t teach. You have to live it. I look around my state, and I see so much that is still broken. I see money misspent and wrong people in important jobs and good people driven out of public service. I see cynical decisions that taxpayers still foot the bill for. I even see people who are dead who otherwise might not be. It’s as if, for ten years, Tom and Daisy Buchanan ran my state.

“They were careless people, Tom and Daisy -- they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Shares