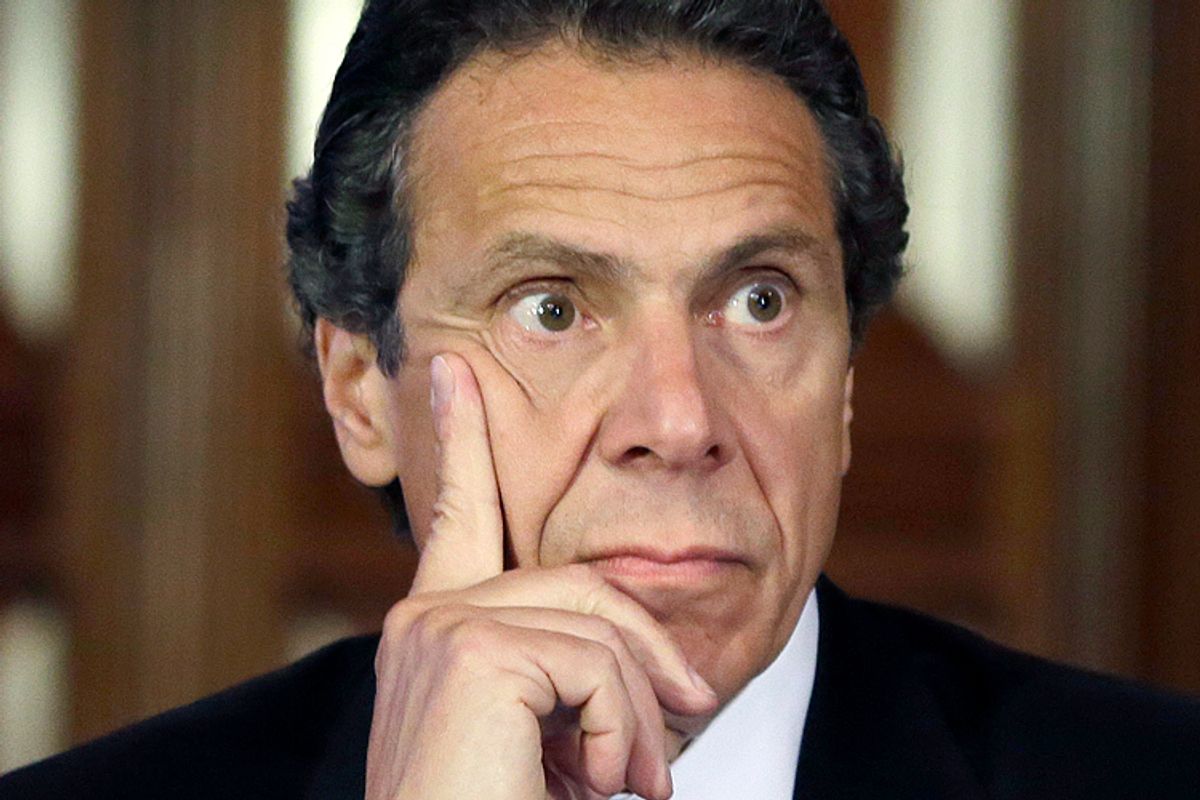

Michael Shnayerson had the misfortune of releasing his Andrew Cuomo biography, "The Contender," after Cuomo’s time has passed as a serious presidential contender. There was a time when Cuomo’s presidential stock was on the rise. In 2011-2012 he passed a landmark marriage equality bill, worked with Republicans, and amassed a massive campaign war chest. Unfortunately, 2014 exposed Cuomo’s personal and political limitations, and even Shnayerson now writes gloomily about his prospects. The sequel will not involve victory parties in Iowa and New Hampshire.

To a national audience meeting him for the first time, Shnayerson portrays Cuomo as a Robert Caro character, someone who can Get Things Done, if you can look past the endless barrage of distasteful anecdotes. To New Yorkers, this is a catalogue of Cuomo’s greatest hits as he bulldozes through state politics decade after decade.

Early in "The Contender," we see an unquestionably devoted young Andrew Cuomo doing battle for his father, three-term New York Gov. Mario Cuomo. Andrew’s political abilities are on display early – his skillful effort to win his father 39 percent of the vote against Ed Koch in the 1982 state Democratic Convention paves the way for Mario’s come-from-behind victory. Andrew comes across sympathetically, totally committed to his father’s political career, without many friends or interests beyond hot cars. The formal and tense Mario-Andrew relationship is probably not envied by most fathers and sons, but the arrangement served them well. Andrew was essential to Mario’s political career, and even though Andrew argued in 2014 that “there are ultimately more negatives than positives to being a famous politician’s son,” without Mario’s influence he would not have landed post-law school jobs with Robert Morgenthau, David Dinkins and Bill Clinton.

Andrew’s own story truly begins in Washington, D.C., recently married to Kerry Kennedy (RFK’s daughter), and working as assistant secretary of HUD. At HUD he works with a manic energy, earning Bill Clinton’s trust and respect. (Though, in an ominous sign of future woes, Cuomo picks a fight with his inspector general, who he claims must report to him rather than operate independently.) Cuomo’s work ethic, a perhaps underreported part of his persona, is essential to his success at every step, and highlighted throughout "The Contender." Shnayerson gently bats aside the critique that Cuomo’s policymaking precipitated the 2008 financial crisis, as some right-wingers have suggested, but even during his tenure there were legitimate complaints about programs that went awry, including a messy scandal centered in Harlem.

After serving as Clinton’s HUD secretary, Cuomo returned home to run for governor. The 2002 primary loss that followed was his self-professed low point: “When you lie in bed and you think of the worst thing that could happen to you, short of death or serious health issues, for me that was the nightmare: public humiliation, public embarrassment, political loss.”

In Shnayerson’s telling, Cuomo’s behavior during the 2002 election is so petulant that it is remarkable he ever recovered from it. He berates staff (“You guys are just chasing the soccer ball. You guys are just scrambled eggs. You call yourselves professionals?”), burns contacts across the state by dropping out of the state Democratic Convention and then the primary, and undermines Democratic nominee Carl McCall, who was attempting to become New York’s first black governor. Adjectives used by journalists to describe Cuomo during that campaign include “mean spirited,” “arrogant,” “grating,” “obnoxious” and “unlikable.” To me, as a former aide on campaigns (not his), his worst offense was refusing to reimburse staff for thousands of dollars in campaign expenses despite having $3 million remaining in his account.

Right after the campaign, Cuomo and Kerry Kennedy divorced, ending a marriage that had long cooled, but not before he dragged her affair into the public spotlight. The passages on Kennedy are sad to read about. The combination of loss and divorce were somewhat by design, given Kennedy’s promise to prolong the marriage for the sake of the campaign.

For all of the agony 2002 supposedly inflicted upon him, Cuomo’s story of personal redemption involved little more than making money financing marinas for mega-yachts in Dubai, passing around leftover campaign money from 2002, and begging the political establishment (specifically, 1199 SEIU) for a second chance. Cuomo didn’t become more humble, just savvier. Hence his 2006 run for New York attorney general and patient scheming while the careers of Eliot Spitzer and David Paterson went up in smoke before his eyes.

When the dust settled on the 2010 election, Andrew Cuomo had been elected governor by a landslide and eliminated his rivals. The only thing missing was a Democratic state Senate, something that we now have ample evidence that Cuomo never wanted. According to Shnayerson, in 2010 Cuomo broke his word to Bill Samuels on helping finance Democratic state Senate candidates in return for Samuels bowing out of the lieutenant governor race. This story would repeat itself, first when Cuomo helped the IDC deliver control of the Senate to the Republicans after the 2012 elections, and in 2014, when he reneged on his promise to the WFP to fight for Democratic control of the Senate.

While the book is quite well-written, people who follow New York politics closely may be disappointed to find little new information about Cuomo’s tenure as governor in "The Contender." Shnayerson dutifully weaves a narrative about guns, gaming, the Moreland Commission, the Committee to Save New York, Bridgegate and fracking, but he is curating stories that have already been reported. Nor is there much on Preet Bharara’s investigation into Cuomo, which could really upend talk of Cuomo as a presidential contender. Cuomo’s fractious relationship with the Teachers Union and cozy relationship with hedge funds would also likely come up if he ever ran for president, but they go largely unmentioned here.

“His story is the iconic story of the American politicians.”

At times it feels as if Shnayerson is trying to shine up his subject a little too hard. Shnayerson claims, “No one was immune from Andrew’s charm when he turned it on,” and credits him with a “charm offensive few could resist,” even though "The Contender" presents little evidence of charm.

More significantly, Shnayerson portrays a hardscrabble kid from Holliswood, Queens: the car mechanic who is never comfortable rubbing shoulders with New York’s elite. This psychoanalysis feels misplaced. First, even Cuomo’s early upbringing was at least middle class: His father was a prominent lawyer tangling with Robert Moses when Andrew was a small child, and Andrew was a teenager when Mario began his campaigns for citywide and statewide office. Second, ascribing his enmity of Eliot Spitzer and Eric Schneiderman to their blue bloodedness feels simplistic; after all, he was similarly antagonistic with Shelley Silver and Bill de Blasio. Maybe he just doesn’t play well with others? Besides, distaste for opulence didn’t prevent him from marrying a Kennedy.

Though Cuomo doesn’t get along with most people, "The Contender" reveals a particular absence of women in Cuomo’s life. Other than immediate relatives and girlfriend Sandra Lee, Cuomo seems to have few female friends or political allies. His 30th birthday party, Shnayerson notes, was attended by 25 men and no women. The political team that follows Cuomo through his career is a coterie of white men: Howard Glaser, Larry Schwartz, Steve Cohen, Joe Percoco, Ben Lawsky and others. Perhaps the little input he gets from women explain his tacky “Women’s Equality Party,” which was widely ridiculed during the 2014 election. Likewise, racial minorities make few cameos in "The Contender," and Cuomo’s racial analysis during the 2002 primary race is particularly squeamish. (“Blacks have three pictures on the wall. Jesus Christ, Martin Luther King, and JFK. And I am a Kennedy now.”)

Those hoping to catch glimpses into what really drives Andrew Cuomo may come up empty -- other than the accumulation of power. Early on, Cuomo explains, “When you advocate for the poorest people in this country…you’re going to end up looking like an old-style liberal. That’s what happened to my old man.” As attorney general and as governor, he followed a method: “he got the headline he wanted and moved on.” Everything had to be sold as a victory, no matter how meager the actual success, such as the 2014 ethics bill that shut down the Moreland Commission (an anti-corruption panel I worked on), and, it appears, the 2015 ethics bill being championed right now.

Shnayerson bounces between Cuomo’s personal and political battles seamlessly, never getting bogged down in morass of state government. As a straight telling of Cuomo’s life, it is well written, a good introductory book. Yet absent from "The Contender" is serious analysis about whether Cuomo was or is still a serious contender for the presidency. The book makes passing references to Hillary Clinton, the overwhelming 2016 front-runner. According to Shnayerson, a Clinton loss would leave Cuomo in position to run in 2020, and even a Clinton win wouldn’t rule out a run from the 67-year-old Cuomo in 2024. Yet no other candidates are mentioned, be they quasi-announced candidates like Joe Biden and Martin O’Malley or tantalizing maybes like Elizabeth Warren. By 2020 and 2024 there will likely be other, more exciting politicians on the scene.

The national buzz that accompanied Cuomo’s early governorship appears to have dissipated by late 2013. Even his crowning achievement, marriage equality, will be a mainstream Democratic position in 2016 (O’Malley also passed the law as governor), let alone by 2024. The notion that he can “break partisan gridlock” might be a good sound bite, but it is unlikely to play well with Democratic primary voters when they learn that Cuomo only worked so well with Senate Republicans because of the deals he made to keep them in power. Even Cuomo’s book, written to defuse the impact of "The Contender," revealed a total lack of public interest in Cuomo. "All Things Possible" has sold around 2,000 copies, a low figure by any metric in the publishing industry.

Shnayerson also gives us only a cursory look into Team Cuomo. No one can win the presidency on his or her own, and the antagonistic, insular behavior of Team Cuomo does not portend well for a national campaign. Shnayerson unflatteringly portrays top aides as mini-Andrews, yellers who harangue Bloomberg staffers in the middle of the night over the poem selection for a 9/11 memorial service, insert themselves into every issue big or small, from Moreland Commission subpoenas to Sandra Lee’s gazebo permit, and brazenly mislead reporters. While working as a special counsel to the Moreland Commission, I was struck by Cuomo’s reliance on the same people from one commission, report or legislative issue to the next, something that seems unsustainable in New York, let alone nationally.

Understandably, working in this environment is exhausting. Schwartz, Glaser and Cohen have all moved on. Who, exactly, would run Cuomo 2016? Who from Cuomo’s inner circle has any experience in politics outside of New York? Such people can be hired, of course, but "The Contender" shows that Cuomo is very slow to trust. This dilemma alone would preclude Team Cuomo from winning a national primary against whatever Plouffe/Axelrod equivalent they ran up against.

Finally, perhaps "The Contender’s" greatest shortcoming is its cursory treatment of the 2014 Democratic primary against Zephyr Teachout and its consequences. Writing about current political figures is a challenge given turnaround times in the publishing industry, so Shnayerson was inevitably going to miss something. Yet for a book about a possible presidential contender, the 2014 Teachout-Cuomo primary showed that Cuomo is far from ready for the national stage. (Full disclosure: I worked on the Teachout campaign after leaving state government, and watched Team Cuomo struggle with this campaign while they dealt with post-Moreland fallout.)

Throughout the short 2014 Democratic primary, Cuomo’s team made tactical mistakes against the plucky law professor’s shoestring operation. The trouble started at the Working Families Party Convention, where Cuomo’s 11th hour attempt to seize the ballot line by pressuring unions agonized the WFP leadership and infuriated rank and file activists. Teachout was gracious toward Cuomo supporters, winning the lasting respect of activists who do so much of grass-roots campaign work.

Cuomo’s next move was a clumsy attempt to kick Teachout off of the ballot for residency issues. His legal case was weak, and the two-day trial aired all of Teachout’s dirty laundry, which might have been helpful to stem her insurgency later. Teachout’s eventual success at trial netted her more positive coverage than ever. Cuomo also realized perilously late in the game that his choice for lieutenant governor, Kathy Hochul, could lose to Tim Wu, and needed Bill de Blasio and other city liberals to rescue her. Cuomo’s own margin of victory, 60-36 percent, was the lowest by an incumbent governor in modern New York history, and unbecoming of a heavyweight presidential contender.

Politically, Andrew Cuomo’s life has been a success. Substantively, he may have already accomplished more than his father. Yet, governing by fear and anger has its shelf life. Andrew Cuomo will need a lot of help if he ever wants to run for president, and when he seeks it, people will remember how much they feared him, not how much they loved, or even liked him. You can govern with fear, but you can’t win a Democratic presidential primary with it. You can’t truly be a contender.

Shares