In “All the King’s Men,” Robert Penn Warren’s 1946 masterpiece fictionalization of Huey Long’s corrupt governorship of Louisiana, the main character is not the governor—named Willie Stark in the book—but instead a dried-up husk of a man named, portentously, Jack Burden. Jack is a journalist made so cynical by the misadventures of his own life and the hollowness of politics that he quits his job to become one of Stark’s nameless enforcers—the dirt digger-upper, the blackmailer, the one who gives you an offer you can’t refuse. Stark is really part of the setting of the book, witnessed from the outside as a force of nature—first rising, then cresting, before the inevitable dissolution. Jack, meanwhile, is the human element. He flops from post to post, a dog kept on a long leash, because he can’t think of what else to do with himself. The story of “All the King’s Men” is really about how Jack Burden comes to terms with being a person—morally, spiritually, romantically—in his time, in his place.

Toward the end of the book there’s a line, almost tossed-off, that illustrates the peace that Jack is eventually able to come to. “The truth gave the past back to me,” he observes, looking out at the gulf. He’s writing about a particular truth he uncovers, which I don’t want to divulge, because it’s worth reading the book yourself. But he’s also writing about something much broader, in his unwilling journey to figure out his life. Jack was not just any academic—he was a "student of history,” as he often says, not without irony. And his name is, unsubtly, Jack Burden. The burden, at least in part, is the burden of history.

“All the King’s Men” is about history, sort of, and for a present-day reader, it’s very much about history. It’s not, consciously, a period piece, but one of the reasons the book is so fantastic is that its narrative is timeless; the details of the story can fall away, leaving just the essence of this one person’s story.

In that sense, at least, it’s almost the exact opposite of “Mad Men,” AMC’s game-changing TV show that is starting its final seven-episode run this Sunday. “Mad Men” is consciously a period piece in every way—it’s a show about the 2010s that happens to be set in the 1960s, a show about examining where our attitudes toward sex, gender, capitalism and inclusion come from, through the deceptively simple lens of a philandering adman with a weird, inconsequential secret. Unlike Robert Penn Warren’s novel-writing, the technology and rigor of “Mad Men” would have been impossible in the era the show is set in; it’s a product of 2009 far more than it is a product of 1961.

In other ways, though, the two narratives have common ground. Jack Burden and Don Draper are two constructed characters who are attempting to live their lives with just a blank slate behind them. Jack is just running away from whatever he used to be, as fast as possible; Don goes the extra mile, and changes his whole identity. Both engage in morally dubious pastimes, playing the charlatan, the trickster, the confidence man. Both are engaged in the work of making ideas more useful to certain moneyed interests—politics is a particularly sophisticated kind of advertising, much of the time. And both have just one woman they seem to really care for. For Jack, it’s his lost love Anne Stanton; for Don, it’s his daughter, Sally. Just as Jack’s transformation hinges on Anne, we’ve seen Don’s transformation pivot on Sally, the only person who looks at Don with such a level, knowing stare.

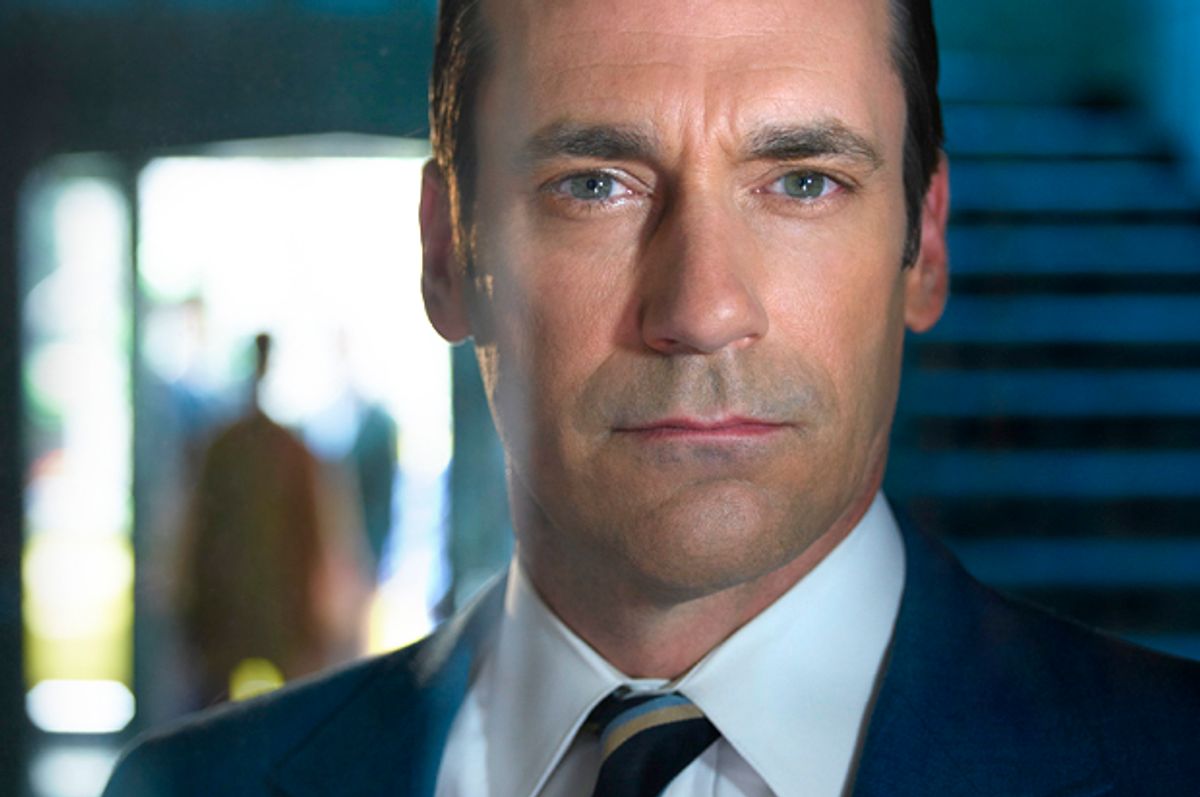

There’s a lot to say—and so much of it has been said already—about how extraordinarily well-crafted “Mad Men” is. It’s written well. It’s directed well. It’s designed (sets, props, sound and costumes) to perfection. It features some of the finest performances on TV today. It’s not a show that is so perfect that you can’t see its flaws—but on the other hand, it’s a show that is so perfect that it can sell its flaws as mysterious design. And it’s a show that has become a cultural phenomenon—influencing fashion, interior design and architecture, as well as the two industries it’s most intimately intertwined with: television and advertising. Less measurably, it’s influenced the most important business of capitalism: style. “Mad Men” is breathtakingly cool, in a way that is both seductive and destructive for its characters. Weiner’s show could be said to be ruthlessly deconstructing “cool,” that thing invented and exploited by admen. The deconstruction spills over the boundaries of the show and enters the wider world—the seductive elements, and the destructive ones, too. Is there anything that's more of a stamp of approval on the accuracy and relevance of “Mad Men” than the fact that the show’s star, Jon Hamm, is now the official voice of both American Airlines and Mercedes-Benz? An airline and a car, the two most American products there are, in their dated glamour, environmental destructiveness and enormous market share. In “Mad Men” itself, Sterling Cooper & Partners chase an airline account and a car account. In real life, advertising firms chase “Mad Men.”

But above all, “Mad Men” is a delicate instrument wielded by Matthew Weiner that excavates the 1960s, the decade that really did change everything, so as to tell us who we are today. I have seen many films set in the 1960s, and I have read books from any number of time periods before the civil rights era. None of them brought home for me just exactly how prevalent and crushing the status quo was. But from the first day of Peggy’s job at Sterling Cooper, “Mad Men” forces the viewer to inhabit the barrage of harassment and judgment that anyone who wasn’t a white man received in this world. The show is devastatingly, meticulously accurate, without a tinge of nostalgia. It might be pretty, but it wasn’t better back then.

Which is to say: “Mad Men,” quite literally, is the truth that brings the past back to us. It is the world’s most humane history lesson, a story that brings to life the world of 50 years ago to show us our own foundations. With “Mad Men” we float closer to a bygone era, to better know ourselves—and perhaps most important, to know what to do next. In “All the King’s Men,” Jack Burden is the student of history, and he takes the reader through his findings. In “Mad Men,” Don Draper is a construction of half-truths that becomes the window through which we all can be students of history. Its primary influence is one that grants extraordinary privilege to the viewer—the ability, for seven seasons, to have the past returned to us, so that we may continue the long process of coming to terms with it. It is that reckoning that I will miss the most.

Shares