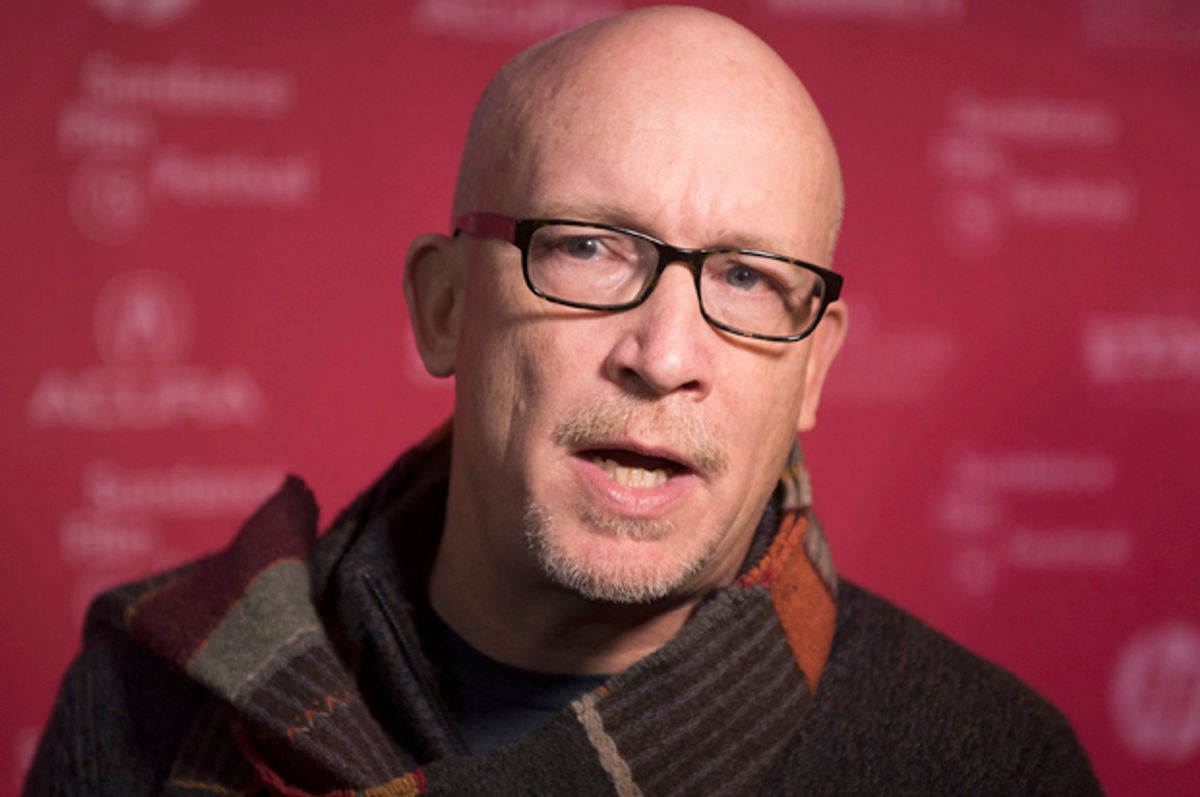

Alex Gibney, the Oscar-winning documentary filmmaker whose explosive exposé “Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief” sparked widespread outrage and astonishment after its HBO premiere last weekend, is on one hell of a roll, even by his standards. This coming weekend, he has yet another HBO movie, made in a gentler and more reflective mode: “Sinatra: All or Nothing at All,” a two-part four-hour special to honor the great pop singer’s centennial, is the first documentary made with the Sinatra family’s cooperation, and incorporates large amounts of archival material supplied by Nancy Sinatra. Then there’s Gibney’s forthcoming theatrical film “Steve Jobs: Man in the Machine,” which he describes as an ethical meditation on the life and career of the late Apple founder. I haven’t seen it, but it sparked considerable debate after its recent premiere at South by Southwest and will be released by Magnolia Pictures later this year.

I’ve known Gibney since the release of his breakthrough film “Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room” in 2005, and he’s always been a startlingly prolific writer, director and producer, with several film and TV projects going at once and numerous others waiting for liftoff. If you start listing the topics of Gibney’s films, they may sound like a disconnected litany of names and issues: What do Eliot Spitzer, Jack Abramoff, Hunter S. Thompson, the Bush administration’s torture policies, Fela Kuti, James Brown, WikiLeaks and Lance Armstrong have in common? In most of those cases – as in “Going Clear,” a collaboration with author Lawrence Wright – Gibney was making a film that amplified, illustrated and dramatized a journalist’s investigative work, so bringing it to a much wider audience. If he didn’t invent that form (and he wouldn’t claim to), he has pretty nearly perfected it.

But that’s not the only method I discern in Gibney’s feverish production. He has made films that had an enormous impact on public debate: “Enron” captured the culture of voracious and immoral greed that had conquered turn-of-the-century capitalism, and “Taxi to the Dark Side,” one of the least likely Oscar winners of all time, focused the nation’s attention for the first time on the atrocities inflicted in our name on “war on terror” detainees. He has made important movies (in my judgment) about issues most people were eager to forget or ignore, including the Spitzer doc “Client 9” and “Casino Jack and the United States of Money,” which explored the far-reaching perversion and corruption of American politics and the legislative process. Behind all of these, and behind Gibney’s more mild-tempered pop-culture docs as well, lies one overarching question: What the hell happened to America in the 20th century? To paraphrase one of the greatest lyric poets of the 1980s, how did we get here?

Gibney will tell you that he takes all these topics one at a time and isn’t overtly concerned with the bigger picture. While he’s a native New Yorker from the educated middle class, with hints of a counterculture background (e.g., the interest in Hunter Thompson, Ken Kesey, et al.), Gibney resists efforts to classify him as a radical or an anti-American gadfly. Indeed, Julian Assange’s core fans widely denounced Gibney as a U.S. government stooge, if not a full-on CIA operative, for the portrait of the WikiLeaks founder he sketched in “We Steal Secrets.” But in my judgment Gibney’s films are slowly filling in a much larger portrayal, one news story and one controversial figure at a time. It’s the incremental depiction of a country that rose up to rule the world, a country founded on promises it has never fulfilled, a country that squandered the fruits of that victory and drove itself off the rails into chaos, corruption and mendacity.

If the delusional worldview and paranoid internal culture of the Church of Scientology depicted in “Going Clear” is an especially dramatic example of American grandeur and craziness, the paradoxical storybook careers of Frank Sinatra and Steve Jobs, with their troubled hothead protagonists and their improbable twists and turns, illustrate the same theme in their own way. I met Gibney earlier this week in his Manhattan office, to talk about his cascade of new projects and the extraordinary reactions provoked by “Going Clear.”

Alex, I understand that you actually hooked yourself up to the E-meter, the device invented by L. Ron Hubbard that’s used in Scientology’s auditing process. Is there any real science to that gizmo? Is it really registering something?

Yeah, it is registering some kind of electrical impulses in the body. It’s like one-third of a lie detector, and they use that to great effect. I mean, people who are audited start believing in its efficacy and then it’s a great tool for doing these things that they call “sec-checks,” or security checks. So they have this long list of things like, have you ever had sex with animals? What kind of animals? Right? And then people believe that if they don’t tell the truth, the machine is going to spot it.

So this speaks to Lawrence Wright’s hypothesis that whatever embarrassing information may exist about Tom Cruise and John Travolta, expressing no prejudice about what that might be, the church has it?

Correct. They know what it is, they’ve got it in file folders and most likely, they’ve got it in videotapes.

What has surprised you about the reaction to the film? First of all, the Church of Scientology has officially released various official statements and websites and videos attacking “Going Clear,” so let’s start there. Is there anything that surprises you about their counterattack?

Not really. It’s kind of textbook. What’s textbook about it is it’s full of so much vitriol and hate, which is, if you think about it, kind of unusual for a church. Sure, what’s his name from the Catholic League, Bill Donohue, will do stuff like that. But this is like textbook, fair game. Straight out of the Hubbard manual. Hollywood Reporter sent them 25 questions and said, “Please respond to these allegations specifically.” And their response was to ignore all of them and just to say, “Alex Gibney is a liar and a bigot and everybody who’s involved in the project are bigots and liars and cheaters.” That kind of thing. So it’s not surprising, but it is amazing to see that kind of hostility expressed. And that’s how they do it.

They have not attempted to offer any specific rebuttals of any kind? Because I certainly haven’t seen that.

No, they just say, “Everything’s false, there are no misdeeds, but everybody involved is a bigoted asshole.”

It’s an extraordinary level of avoiding the issue, isn’t it? They avoid the questions more completely than the Soviet Union ever did, than the Catholic Church ever did.

Absolutely, they make all those institutions look good. If you dig down deep, it is a little like the Soviet Union or some Orwellian organization. For example, they will say, “Marty Rathbun is an admitted liar.” And it’s true. Marty [a former Scientology spokesperson] admits that he lied -- on behalf of the church! Then they went after Spanky Taylor [John Travolta’s former personal assistant and church liaison] and said, “After she left the church she got involved in a horrible organization that was predatory and was so bad that it was sued out of existence.” They don’t say that the Church of Scientology sued it out of existence. It was called the Cult Awareness Network and it was designed to help people. Then it went bankrupt and Scientology bought its name. So if you wanted to go get help from the Cult Awareness Network, you were actually walking right into the Church of Scientology. Amazing.

Now people like Bodhi Elfman and Danny Masterson [both current Scientologists] are coming out and making these comparisons: “How would it be if there was a documentary done on Jews in which you only interviewed Nazis?” So that gives you some sense of a skewed perspective. But to give the devil his due, they used to post these anonymous sites and smear people. Now they’re coming right out front: These are official Church of Scientology sites, putting bull’s-eyes on people’s faces.

On yours?

No, but this woman Sara Goldberg has a bull’s-eye on her face. They’ve done a video on me -- they went after my dad, who’s dead. They’re saying he had some involvement with the CIA back in the day, which is probably true. But so what?

Here's what we won't know for a while: How wounded is the church, both internally and in the world, by this extremely bad moment of publicity? I mean, this has to be the worst moment of publicity that they’ve ever had.

I think that’s true. There were an incredible number of people who watched the broadcast on Sunday night, and we’ll have to see what comes of that. Now people are circulating petitions asking for the church’s IRS exemption to be withdrawn.

Hasn’t Sen. Ron Wyden has been looking into that?

Theoretically. He sent a query over to the IRS, which could either mean he’s serious about it or it could mean that he wanted to get some constituent off his back. But he is one of the people on the Senate subcommittee that would be in charge. There’s plenty of precedent for denying that, even for big organizations. The Supreme Court took a case involving Bob Jones University, about 10 years before Scientology got its exemption.

If you think about it as a church that practices disconnection, a really vicious form of cruelty toward families, a church that hires tons of private investigators to harass people. Because their M.O. is not beating people up, they don’t do that. They try to torment you psychologically, which is perfect for this organization that despises psychology but is all about mental mind games. Some of our people [i.e., who spoke out in “Going Clear”] have been threatened physically. Some of them have been threatened with having their homes taken away. Then there’s all this physical abuse that’s gone on. It’s hard to understand why that is a tax-deductible activity, why that should be supported.

They’ve been effective for a long time at getting people to back off, because they’re so dogged and so litigious and so tough. Like I said, we went to networks to get footage and couldn’t license it. We “Fair Used” it anyway, but it wasn’t worth their trouble, I’m assuming. They wouldn’t tell me.

It seems to me they have a really big problem. You guys more or less accept the premise that this is a religion, since we can’t clearly decide what that word means anyway. But they have a problem that no other world religion has: They have a huge bureaucracy and tons of money, but they no longer have a base. As Larry says, they may have 20,000 or 30,000 active members in this country, and maybe twice that number around the world. That’s fewer than the number of Rastafarians in the United States. It’s one-fourth or one-fifth the number of professed Wiccans in the United States, people who don’t even have a church. So it’s like they’ve got the superstructure of a religion, but no flock. Is that going to kill them eventually?

Well, it’s hard to know. If you’ve got $3 billion -- and that’s just an estimate -- and you’ve got good investment bankers working for you, you should be able to make 10 or 15 percent on your money. That’s $300 million to $450 million a year. With that kind of money, even if you have fewer and fewer parishioners – which shows you where I come from! -- you can hang around for a long time.

Then there’s Larry’s great phrase, “The Prison of Belief.” This is the church that won’t let you leave. If you leave the church and become a critic, they start hammering you without mercy. What other church is like that? You can decide one day, “I’m not going to Mass anymore.” You don’t have a bunch of people with Go-Pros on their heads showing up at your door. First there’s the mental part about you can’t leave because you don’t want to leave all your people and friends behind. Then if you do leave, they go after you hard.

I can already hear the trolls on the Internet reminding us that in some Islamic countries apostates are persecuted. That’s probably a valid point of comparison. What surprised you about the reaction of Hollywood? The trade press has done lists of all the celebrities and industry insiders reacting to the movie, many of them with astonishment. These people worked in the community where Scientology is based, the industry that is Scientology’s focus, and they really didn’t know any of this stuff?

I think there is a lot of surprise out there. Until I read Larry’s book, I wasn’t that well educated. I think for those people who read the book and those people who saw the film, it’s a jaw-dropper to see those images. Those big Scientology ceremonies inside the L.A. Civic Center.

Yeah, it’s like the Nuremberg rallies staged in Vegas. Those are pretty intense. How did you get those?

Fair use. We looked high and low; the Russian Internet, individuals. We brought it all in, and I think we were the first people to really aggressively push the Fair Use Doctrine in regards to this. We believed it. We spent a lot of time with lawyers figuring out exactly what we could use and how much we could use. But that stuff is a jaw-dropper. Sometimes we’d find stuff that we could license. Like, we found the guy who originally went on board the ship and shot that interview with L. Ron Hubbard. He had all these outtakes that were in his basement.

There’s obviously no way that you could put everything that was in Larry’s book in the movie. Is there anything that you wished you could have gotten to? Some people have brought up the stuff about the mysterious whereabouts of David Miscavige’s wife.

Yeah, Shelly Miscavige is one of them. It’s a really interesting story because it’s related. There were also people – and this stuff is not in Larry’s book -- but there were people who were so close to talking that would have been great, because they were well-known celebrities. Former members, or people who were half-in, half-out. There are plenty more individual episodes, similar stories to the ones we have in the film. We had to pick and choose. Our four-hour cut includes a lot of that material.

Larry speculates that it might be possible for the church to reform itself by doing what they did before on the issue of homophobia, and pretending that Hubbard’s bigoted and hateful remarks basically never existed. I think he’s being overly generous. I can’t imagine an organization that is this paranoid and this hateful finding a way to reinvent itself. Can you?

No. Look at what’s happening now with Pope Francis and the Catholic Church. The weight of history is so strong, much stronger for the Catholic Church of course. But in the case of the Church of Scientology they would have to fundamentally uproot their belief system. Whether he was a bigot or just a creature of his age, Hubbard was virulently anti-gay and thought it was a disease that could be cured. How do you fix that unless you come out and say, “You know what? Hubbard was wrong about a lot of things.” And that’s hard to do. That’s what was so interesting about these individuals in our film: It was hard for them to wake up one day and say they had been wrong for 30 years.

I don’t know if you read this piece in the New Yorker recently, about the Jean McConville murder in Northern Ireland? It was a fascinating piece and one of the aspects that caught my eye was this one woman [Dolours Price] who was basically a hit woman for the IRA. She was very attractive, ended up marrying Stephen Rea. But when the Good Friday Accords happened, suddenly all the certainty she’d had that allowed her to believe that the end justified the means had been removed. And it sent her into a tailspin. Once that certainty is gone – I mean, it’s a wonderful kind of narcotic. I think that for Danny Masterson and Bodhi Elfman, it probably feels good to say, “Those are hateful bastards saying this stuff.” Because it’s pure; it may be hate but it’s pure hate, and it feels good because you’re certain. But when your certainty is removed, what’s left?

I was thinking about this film in terms of your work, relative to all these films you’ve done about the crazier aspects of America: Enron and the Bush torture regime and Jack Abramoff. This story is about one dubious religion that most people think is weird, but on a metaphorical level it’s about the dangers of belief, or the prison of belief, as Larry puts it. And that has much wider application.

Absolutely. That’s why we spent a lot of time focusing in the first third of the film on how people got in to Scientology. Because if you go right to the OT3 and all the crazy upper-level stuff about Xenu and souls trapped in volcanoes, it’s easy for all of us just to say they’re just wackos. But if you spend time thinking about that other stuff, then it implicates all of us in belief systems, whether they be political or religious. But I thought you were going to go to the whole idea of how interviewing is like auditing.

That might be true, too. I didn’t think about that.

Because that comes right out of the main title sequence. Marina Zenovich is speaking the words of an auditor, and you hear different people responding to the auditor’s question. Then the auditor’s voice changes into my voice and then we take out all the sound filtering until at the very end it’s just a flat question, where I say to Paul Haggis, “Tell me about it.” It struck me as I was doing the film how much interviewing is like auditing. For the best auditors -- like when Jason Beghe talks about what a great auditor Marty Rathbun is -- it’s all about that idea of trying not only to understand and engage but also to be empathetic. To listen and to convince that person that you’re going to honor what it is that they tell you.

Do you know Janet Malcolm’s famous quote about the interview? I’m pretty sure it’s in her book on Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. I'm sure I don't have this word for word, but she basically points out that an interview masquerades as a friendly exchange but that’s an illusion. It’s really a subtle exercise in mutual influencing and counter-influence.

I know that quote, and I should go back and read that piece. To me it’s a little too cynical. There’s no doubt that the interviewer and the interviewee are playing a kind of game, but I think if you operate under the idea that you’re there to exploit that person, then the empathy is gone and I think it’s a serious problem. I find when I interview people I’m not liable to be harder on them. I’m liable to be easier on them, because I’ve had a personal exchange with them. I think long and hard about putting stuff in that might make them look bad even though I often get to that place. Like when we did “Taxi to the Dark Side,” I liked most of those kids [military interrogators interviewed in the film]. But those kids had tortured somebody to death. It took me a long time to get to a place where I could put back in some of that detail. In rough cut, we realized that we were basically saying they didn’t have any responsibility and that they’d been put up to this. At some point that was just wrong. They had some responsibility too, and to put back in some of that detail was hard because they had been relatively open and honest with me. Now, the ties that bind are severed when people start lying to you rapaciously. That’s different.

Lillian Ross, in her essay on reporting, says something that’s almost the opposite of Malcolm. She says someone who has granted you an interview has granted you their friendship, and you have to accept the responsibility that comes along with that. Not the responsibility to lie or to cover up bad things they did, because that’s not what a friend does. But you incur a personal obligation to that person.

I think you do. I wouldn’t go so far as to say friendship, but you have a relationship with that person and you have to find some way to honor their willingness to open themselves up. I now think a lot more about that when I’m making a film, in terms of how I cut things together. Is this fair to our exchange? Is this fair to who that person is or was? Could I take this film right now and show it to them and even if it’s critical, say, “I think this is fair, and here’s why.” That’s the acid test for me. Can you sit with that person in the room, and even if they don’t like it, you can say, “This is why I think it’s fair”? That to me seems to be a pretty good test.

That’s the only part I didn’t like about what I remember about the Janet Malcolm thing. Because her take seemed to be: You interview somebody, they tell you all their secrets, then you run away and you write something nasty and then you hide. That seems kind of fucked up.

I would like to say that she has something a little more complicated than that in mind.

Well I think she raised important questions, because at the end of the day when you’re having an exchange with somebody, you’re saying, “I empathize with you and I’m on your side.” You’re not really on their side. At the end of the day, you’re on the side of the audience. Your job is to try to tell a compelling and important story to your viewers. So you’re not really on the same side.

And you know better than almost anyone in this business the tendency of people, when being interviewed, to say things that they should not say and reveal things that they should not reveal.

Yeah. I’ve been on the other side, too, and I’ve done it. We all have this urge to get stuff out. The hard part is getting people in the chair. It’s not that hard to get people to talk once they’re in the chair.

Your rate of production at the moment is kind of unbelievable. Let’s switch to what’s coming next, your two-part film on Frank Sinatra that premieres this weekend on HBO – the first documentary made with the cooperation of his estate. That’s in a different register, it’s fair to say. It’s not entirely laudatory but more a tribute than an exposé. Tell me how you came to that project.

Well, about four years ago Frank Marshall [a veteran Hollywood producer and executive] reached out to me and said, “I’m in touch with the family and they seem ready to do something – and the 100th anniversary of his birth is coming up.” I have to be honest and say that when I was just coming out of college, Frank Sinatra was this old guy who was friends with Spiro Agnew. So I can’t say it was the thing that rose to the top of my list. But Frank said, “I think you’ll really be engaged by the story,” and I was. Then the question became, this is a guy where there’s been a lot of ink spilled and a lot of film done, so what is my way in? Then I had a meeting with Nancy Sinatra, and she said she had this film of the 1971 concert he did in Los Angeles, his “retirement concert.” It hadn’t been much seen and certainly had not been properly restored.

As I thought about it, it got more interesting: For some reason that he never explained to anyone, Sinatra decides to retire in 1971. He doesn’t stick to that, of course, but if we presume he meant it at the time and everybody thinks it’s the end, then this is his final statement, his life through song. Using that concert to structure the film, that seemed like an interesting way to go. From that came all this other stuff because the great thing about Frank Marshall’s relationship with the family is that we were able to get access to all these audio conversations that Sinatra had with a bunch of people. They were very candid and full of “fuck this” and “fuck that.” It was him talking off the cuff, not like the interview he did at the time with Walter Cronkite, which is not that great.

That clued me in to the idea that maybe we do it all that way -- all the interviews should be audio interviews only. You stay in the moment of whatever time period that was and you’re not worried about which interview you’re using when, or whether it’s archival or not. You’re just in that moment. So I found my way in. Then it became a life-and-times story, because his career was so long and his rise from the streets of Hoboken across the river is such a great story. It’s “Great Gatsby” territory.

Did you have any difficulty with the family? I can see why you’d want all that material, but I’m sure you wanted to remain in control of the project, and both Nancy Sinatra and Frank Sinatra Jr. have been intensely protective of that legacy.

There were some arguments along the way, but at least in terms of the contract, I had final cut. That was part of the tenor of it going in: I was supposed to be able to do pretty much what I wanted to do.

It’s probably not fair to say you go soft. But there are a lot of other narrative approaches one could make to this guy, looking at his history with women, his history with the Mob and the Kennedys, his relationship with race and politics, his switch from the left to the Reagan right, all of that. I completely agree that he’s the greatest popular singer of his period, a guy who blended the jazz and pop traditions like nobody else, an iconic American and an iconic performer. But while your film certainly brings up the darker stuff, you don't dwell on it.

I would say that this is 2015, and it’s Frank Sinatra’s 100th birthday. It’s a Valentine. Not one without its creases, but generally speaking it’s a Valentine. What I got into and had never fully appreciated before was his ability to be a storyteller in song, particularly with the darker ballads. You could believe that I would be drawn to the darker ballads!

Yes, of course. The “blue period,” the Ava Gardner period. The woman who broke the heart of the ultimate ladykiller, and did American popular culture an immense service.

“I’m a Fool to Want You” -- that is an awesome song and one of the few that he wrote, or co-wrote. Or “Only the Lonely.” Technically, he learned how to phrase things so that he never had to pause just because he had to take a breath. It was always about when it was right for the story. And he puts himself in character, like in “Angel Eyes.” He did his best acting when he was singing. For all the clips that we used, I’m not that big a fan of Frank Sinatra the actor.

Very limited. He had his moments, but most of those are in “Man With the Golden Arm,” which tells you something.

Right. But as a storyteller in song, he was awesome. So I think there is room for another Sinatra comeback in pop culture. Whether that’s a second comeback or a third comeback I don’t know. I’m also a big fan of “New York, New York,” as corny as it is. It’s a parody of itself in a way, but it also is about the power of ambition. He sings it with such earned enthusiasm, the kid who came across the river from Hoboken. You can’t not like that.

I’ve always thought that it has an oddly ironic aspect played at the end of Yankee games. The specific vibe that they’re going for is only partially achieved by playing that song in the context of the Steinbrenner family’s big cathedral. I’ve always enjoyed hearing it after the Yankees lose.

I’ve actually used that song in another film. I used the version by Cat Power in “Client 9,” my Eliot Spitzer film. I always thought that was like Samson’s song, sung by Delilah. But it’s easy to see the irony in it too. It’s about ambition, but there’s a light side and a dark side to ambition. That’s why I put Bernie Madoff and John Gotti in the montage at the end.

Let’s talk briefly about your Steve Jobs film, which recently premiered at South by Southwest. When do the rest of us get to see it?

It’s going to open the San Francisco Film Festival, so that’s going to go right into the belly of the beast, which ought to be interesting. Magnolia bought it and they’re going to take it out either in late summer or early fall, because the Danny Boyle film on Jobs [the narrative feature “Steve Jobs,” with Michael Fassbender in the title role] has been announced for Oct. 9, and we want to make sure we’re ahead of that.

I’ve skimmed a few of the early reviews, but give me your teaser on the film. How does your approach to Jobs differ from the conventional wisdom?

It’s an impressionistic rumination on his life and what it means to us. I didn’t want to do a dutiful, stone-skipping, “Here are all the events in Steve Jobs’ life” movie. But I was interested in the idea that, when he died, people all over the world who didn’t know him from Adam were weeping. I mean, this guy was not like Martin Luther King Jr. or John Lennon. He was a businessman. But nobody is going to weep for Lloyd Blankfein when he goes. [Laughter.]

No. Or Bill Gates either, I think.

Or Bill Gates, despite the fact that Bill Gates has contributed more to make the world a better place than Steve Jobs ever did. That’s one of the things we get at, because what I got interested in was values. Not just the story of technology, but the story of values. Why do we care so much about him? And I think the answer -- I hate to say “the answer,” because then why bother making the movie -- but one of the answers is that he was our guide through this world of the computer. He introduced us to it. He made the computer warm and fuzzy. He made us feel like we were one with the computer. He came very much out of counterculture. He took acid, he went to Reed College and dropped out, he traveled around the world. It was all about “Think Different,” and putting up billboards with Martin Luther King Jr. and Cesar Chavez and Rosa Parks.

Where did those values take us? By the end, they didn’t take us to such a nice place, although there are aspects of his life that I find very important and moving. For those who see the film as a slam, they’re looking at the wrong end of the telescope. Because a lot of the film is about us, it’s about how we deal with our machines. There’s a small group of people in the film, and they’re not always the ones you would think of. So I hope it ends up being an interesting and in some ways unexpected portrait. We spent a lot of time on his affection for Zen, for instance. We found some great footage of his spiritual adviser, Kobun Chino, talking about his first exchanges with Jobs. So it’s a meditation on many aspects of this person’s life.

Well, there’s such a contrast with Jobs. We have this person who was really a revolutionary and a visionary when it came to understanding the way people use technology, and then we have the effect he had on the culture of the American workplace.

We definitely talk about that. And as I say, there's the question of values, expressed in terms of how Apple used and uses its corporate power. It’s one thing for Jobs to give the finger to IBM as a young man. But when you’re atop the most valuable corporation in history and you’re still giving the finger, to whom are you giving the finger?

Yet Apple still somehow has this cultural cachet of being an underdog company who we're all supposed to root for.

Yes! And how that happens, I just don’t get. Last year I did a film about James Brown, and there’s a lot that’s similar about James Brown and Steve Jobs. He’s an awesome performer, on stage at those Apple events and presentations. Most people think of him as Edison. Steve Jobs was not Edison -- he was a lot closer to P.T. Barnum. But he was smart enough, like James Brown was, to surround himself with an awesome band. And back in the early days, he figured out how good they were and was like, “You’re coming with me. I may take all the credit, but you’re coming with me. I’ll make sure you make a lot of money so you don’t leave.”

I’ve wondered about the similarities between Jobs and Henry Ford, who seemed to have a similar sense of the relationship between consumers and new technology.

I guess so. In the sense that Ford made people comfortable with the automobile, that idea I think is right. But think about Ford’s idea that it was important to pay his workers enough money so they could buy the cars they made. If you look at Apple in China, you don’t see an attempt to be the highest-paying employer. It’s a tough place, China, and it’s a place that’s going through an industrial revolution. All of that is not about Apple. But still, is it unfair to expect more from the most valuable company in the world? Is it unfair to ask Apple to “Think Different?” For me, those are important questions.

"Sinatra: All or Nothing at All" premieres April 5 and 6 on HBO. "Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine" will open in theaters later this year.

Shares