Fifty years ago, Edie Sedgwick began shooting the lead role in Andy Warhol’s “Poor Little Rich Girl.” Just 22 that March, Sedgwick, whose American-regal ancestry dated back to the colonies, found herself in Manhattan after a Southern California childhood that was so unhappy and plagued, it’s practically Greek: stints in boarding school as a member of an arty and erudite in-crowd in Cambridge after time in gothic mental homes. She battled eating disorders and dealt with what was by many accounts a wildly abusive father. Two of her brothers died, one right after another — Robert in a motorcycle accident on New Year’s Eve, after losing Francis (nicknamed “Minty”) to suicide the previous year.

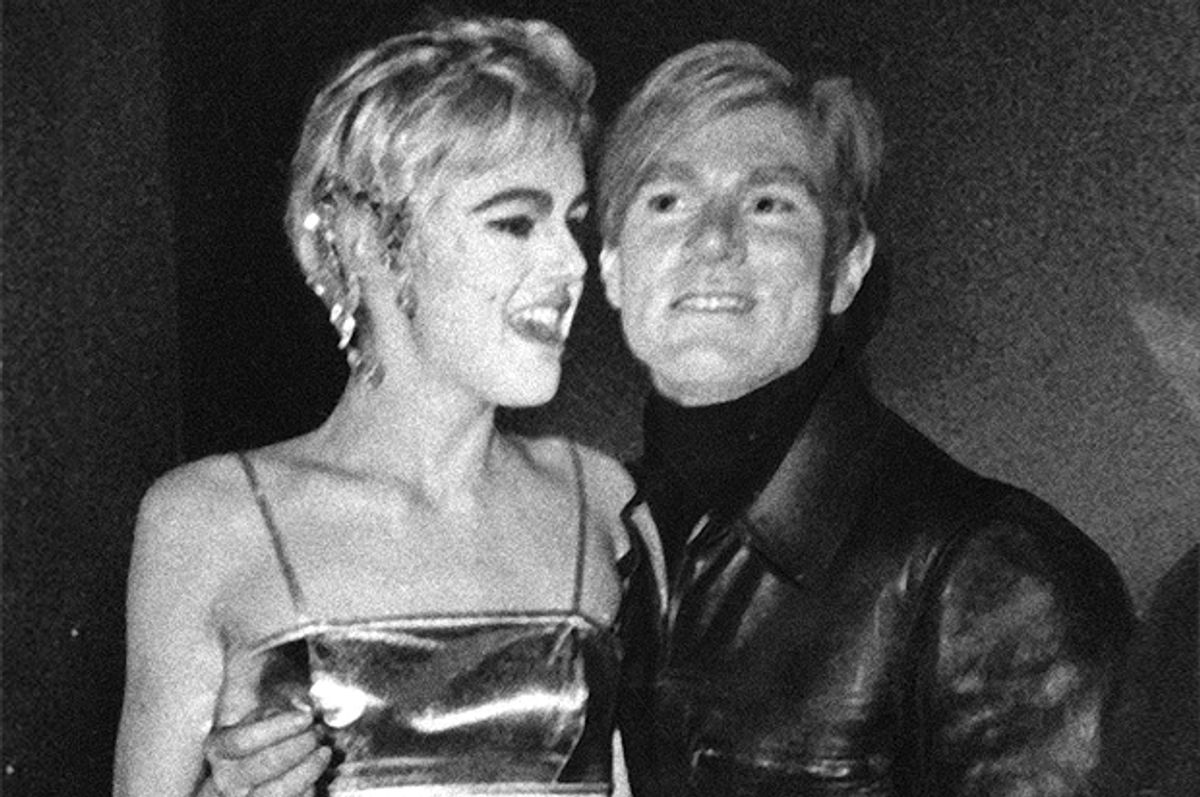

Sedgwick met Warhol at a party in film producer Lester Persky’s apartment that spring. He was the most notorious visual artist in the world, but he, too, was struggling to reinvent himself as more than a painter. A long-legged and loud beauty with the easy entitlement of privilege, Sedgwick quickly became the painfully shy Warhol’s true muse and helped him transition away from the mechanized silk screening that he was growing weary of toward a kind of uncharted, Hollywood-inspired yet New York-anarchic glamour. Warhol was swishy and nearly twice her age and yet, whatever you want to call their kind of love it was, by nearly every account, mutually thrilling — at first.

They began to appear in public dressed alike, with Edie deliberately paling her skin. “She had a slight olive complexion, but she applied white makeup and, what they called at the time, pixie pink lipstick, she kind of invented that look with lip gloss and feathery, false eyelashes,” said playwright and author Robert Heide, who, along with writer Ronnie Tavel, was hired by Warhol to draft scenarios for Sedgwick and her fellow “Superstar” players.

Effortlessly creative, Edie also dyed her cropped brown Jean Seberg hairdo platinum, then colored the roots to suggest artifice. “That’s very fashionable right now,” said Heide. Indeed, it’s a style that’s grown beyond being common to punk rock and New Wave, but at the time, it was both witty and shocking in a time when women and their beauticians took great pains not to let a single dark hair peek through. Such prophetic notions, 50 years later, distinguish Sedgwick. She is, likely even more than Warhol himself (who was not from wealth or aristocratic breeding) an important bridge from high to low art, from “uptown” to “downtown,” “penthouse to pavement,” a structure that the punks, the New Wavers, the indie kids, drag artists and the hipper echelon of traders routinely cross.

In the spring of ’65, Edie was the revolution. She’d been dubbed, well, a lot of things: “It Girl,” the “Youthquaker,” the “Girl in the Black Tights.” Her films for Warhol and her appearances in Life and the Diana Vreeland-steered Vogue, and on television made her both a household and a hipster name before anyone really knew how to straddle the void between.

Edie, like many pioneers, didn’t figure out how to profit from any of it. To call her the Paris Hilton or Kim Kardashian of her era would not be inaccurate, but both of those women are experts in turning rebellion into money. And it’s the cool, often discontented kids who keep her flame burning — and her grave clean — 50 years on, anyway. Her brash but wounded voice is the GPS system out of suburbia for the Manhattan-bound outsider. Her angel face on the promotional material for her final film, the autobiographical “Ciao, Manhattan,” posthumously released in 1973, is like a St. Christopher medallion, with its Kohl-blackened sockets, beauty mark and serene, almost resolute expression, and it still graces T-shirts, stickers, lock pages. “It’s like Jesus Christ looking up to Heaven,” Heide said.

All you have to do to bare witness to Edie’s suffering is to actually watch “Ciao, Manhattan,” which was shot over half a decade, following Sedgwick’s exile from the Factory in ’66 (rumored to be a fallout with a jealous Warhol over her dual membership in Bob Dylan’s rival, hipster faction). They should screen it nightly in rehab centers. Sedgwick’s character, Susan, looks dazed, dances topless in a drained swimming pool for a goober named “Butch” and mumbles aloud (“I oughta call Diana Vreeland in New York. Could you hand me the telephone, Butch? It’s under the magazines over there, and some vodka and my lip gloss?”) and to herself in shimmering voice-over. There’s a black-and-white Alphaville-like subplot involving a dealer/superstar named Paul America and his gruff kingpin boss. As Susan, the veil is almost too thin for Sedgwick, and both seem to know that the end is near.

And yet even when stumbling, there’s something holy about Edie Sedgwick. Her suffering is not meaningless, at least not to those who use it. Sedgwick, given the fate of her two brothers, unsurprisingly had premonitions, and spoke often of not living to 30, but it’s her afterlife that’s proven most remarkable. Dead drug addicts are a dime bag a dozen, but not everyone can become a modern, secular deity.

“I think of Edie as a saint in the Catholic martyr sense,” said Christian Ellermann, 24, a self-described “club kid turned advertising strategist.”

“She has all the beauty and tragedy and recognizability of Saint Sebastian, beautiful and androgynous, riddled with arrows. Or Saint Lucy, with her eyes on a golden platter. It's that intermingling of glamour and death,” said Ellermann.

Sedgwick has been the subject of poems, songs —both good and bad — and a classic oral history (1982’s “Edie,” written by Jean Stein and edited by George Plimpton). It’s become a kind of rite of passage for a young actress to nurse an Edie project to at least pre-production, from Molly Ringwald (who was going to be directed by Warren Beatty) to Natalie Portman (reportedly with Mike Nichols). Lindsay Lohan made an Edie biopic but forgot to shoot a movie, and Sienna Miller actually shot a film (2006’s “Factory Girl”) that wasn’t half bad (at least Guy Pearce’s Warhol was better than David Bowie’s or Crispin Glover’s, if not Jared Harris’).

But that’s not likely the last we see of Edie on-screen, since she isn’t going away any time soon.

“Little Miss S. in a minidress,” Edie Brickell and the New Bohemians sang in 1988 (one of the good songs). “Living it up to die, in the blink of the public eye.”

Sedgwick’s legacy has only grown with each generation: “I've always been hero-oriented,” a young Patti Smith told Interview magazine in 1973, a year after Sedgwick’s death. “…The closest, most accessible god was a hero-god: Brian Jones, Edie Sedgwick, or Rimbaud because their works were there, their voices were there, their faces were there. I was very image-oriented.”

In other words, it began almost upon her death and has continued unabated. The other day I was scrolling Instagram and I noticed that Lena Dunham had posted stills from “Ciao, Manhattan.” How the hell does someone Lena Dunham’s age know who Edie Sedgwick is?, I wondered to myself, before thinking, well, the same way that you know who she is, stupid. I was 3 years old when Edie died, and there I am, on the cover of my 2013 memoir “Poseur” (all about coming into the City from the Island in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s to pursue the great, reinvention dream) wearing an Edie T-shirt from Trash and Vaudeville on St. Mark’s Place. How easily we aging hipsters forget as each new teen makes his or her crucial Edie discovery.

“The short answer is that Edie Sedgwick was very photogenic and died young, thus preserving her forever in the Warhol amber of stylish '60s hedonism,” wrote writer/performer Ann Magnuson in an email. “She was the epitome of that free-for-all adolescent decade and came with a bank account which feeds into every American's fantasy of freedom. Edie also exhibited that special brand of fearlessness, aka, ‘crazy,’ which is fueled by a potent mix of drugs and family dysfunction. The combination of her sexual availability and wounded-ness appeals to men who have a usually unconscious desire to rescue their mother and her anorexia appeals to women who always think they're too fat.

“But there is something darker underneath. Biographical evidence points to Edie's early sexualization. In Jane Fonda's autobiography (‘My Life So Far’), she discusses her own mother's early sexual abuse (and suicide) and believes that sexually abused girls grow up to exude a damaged vulnerability which then takes on a sexualized glow as they mature (a glow her mother had as well as Marilyn Monroe). That allure is then misguidedly interpreted as sex appeal. So these women are less Sex Symbol and more Sex Abuse Symbol.”

Magnuson closed her email to me with this: “Had Edie lived I am not sure she'd hold as much fascination.”

She might not have ended up like (the great) Sylvia Miles. It is hard to imagine a senior citizen Edie being all that compelling. “She probably wouldn’t like it,” said Heide.

But surely there was more to Edie than the fact that she was a member of the 28 club. Sedgwick would have almost surely gotten a kick out of those “dress up like Edie” fashion guides, which help you navigate a world of striped tees, chandelier earrings, fur jackets, cocktail dresses and lots (lots) of black eye makeup. But would such a thing even exist if she wasn’t such a comet?

Pointing out the myth-building benefits of an early death seems elementary (if Bob Dylan had died in his ’66 bike crash or Valerie Solanis had succeeded in murdering Warhol, surely both men would be saintly too, or more so than they already are). If there wasn’t something else to Edie, she wouldn’t have lasted in a town that routinely shrugs at all matter of victimhood and perceived weakness — drugs, poverty, the suddenly unfashionable — and harbors little or no sentimentality about its unofficial landmarks. Edie might not have survived modern Manhattan, but no one can argue that she’s vanished from it. “She didn’t do all that much,” said Heide. “But she did enough.”

Shares