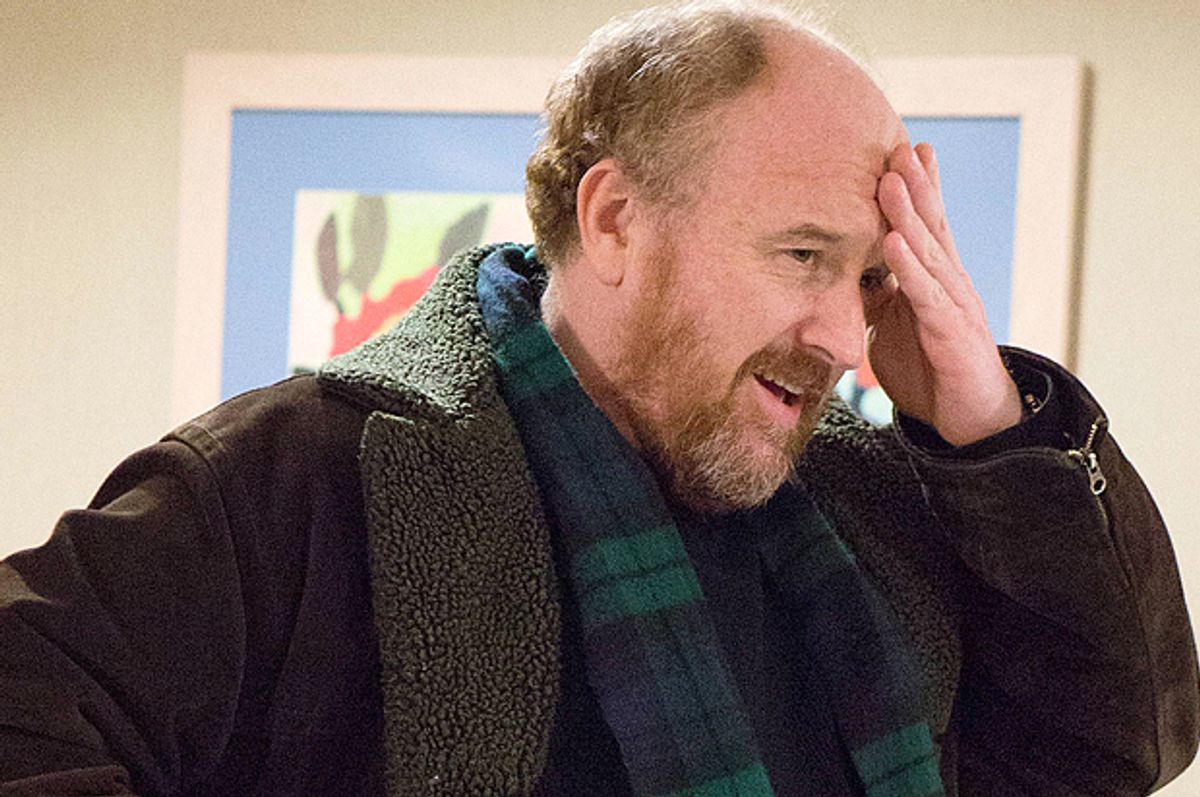

Last night’s “Louie” takes a fascinating hairpin turn in the back half of the episode: After attending the wrong potluck and doubling back to correct his error, Louie is forced to confront the futility of trying to connect with his stuck-up fellow parents from his daughter Jane’s elementary school. Some of that hopelessness is his own fault—there’s that mumbled “better than you” to the woman asking about the violin lessons, after all. But some is the particular milieu of the extremely bougie New York parent—perhaps the most uniquely self-involved group on the planet. Fellow parent Marina (Judy Gold) is hosting the potluck, and doesn’t get on with Louie in the slightest; it doesn’t help that he wants to make fried chicken when she wants a dessert, but she’s also just completely unimpressed with him. Louis C.K. makes sure to depict both how pathetic his character Louie is in the moment, as well as how openly rude Marina is. (In one of the episode’s most lovely grace notes, Louie eats fried chicken while standing up at the buffet table, and another balding man in a black T-shirt sidles up to do the exact same thing. The two barely exchange words.)

But then the story—already dark, already punctuated with disconnection, already scored by the hectic banjo-playing of a random musician in Washington Square Park—takes a turn for the almost absurdly brutal. Marina and her partner, Danila, introduce Julianne (Celia Keenan-Bolger), their very pregnant surrogate. A fellow mom says, “May I?” asking to feel the baby kicking. But it’s Marina, not Julianne, who responds, “Oh sure, go right ahead.”

The interactions between all three continue in this fashion—with Marina, mostly, doing all the talking, and very peremptorily making all the decisions for Julianne, a woman who is barely offered a chance to speak. Marina is very tall—as is the friend she’s speaking to—and androgynously dressed, too; Julianne is petite and unmistakably feminine, with her pregnant belly. The effect is worryingly oppressive. Marina, Janella and the friend are talking over Julianne, describing when she was impregnated, how she will give birth, what will be done to her body. Marina is insisting on a natural birth. “No meds,” she says, pointing to Julianne’s head. Julianne says nothing, and no one addresses her, either; she’s just a walking uterus. It’s only Louie who feels uncomfortable about it, and tries to say something to Julianne; Marina’s response, curt and dismissive, is, “It’s private. This is a private conversation.”

It’s a charged scene. In the midst of a presumably extremely liberal couple’s potluck, here’s an act of callousness so casual that it reads almost like human slavery. She’s reduced to being voiceless and pregnant by tall figures that talk over her head. Julianne is subordinate, infantilized, used—and it’s part of the culture. And Marina’s rebuff to Louie about “her” pregnancy invokes the right to privacy, which points an awkward, zig-zagging finger back to Roe v. Wade, of all things.

That undercurrent of policing what a woman is allowed to do with her own body is ultimately the climax—literally—of the episode; Louie insists on helping Julianne home, and while he’s using her bathroom, she starts sobbing, a combination of feeling horribly isolated and, she says, pregnancy hormones. In comforting her, they move to kissing, and then Julianne insists that he have sex with her right there, from behind, in the entryway to her apartment. Louie, always the gentleman, complies—but in the midst of her orgasm, her water breaks.

The next shot is of Louie in the hospital, when Marina and Danila show up. Marina is furious—both because Louie might have “jizzed all over” her baby son’s face, and furthermore that her planned natural birth will be instead a hospital delivery. But really, she’s mad at Louie for encroaching his penis on her property: Julianne’s body, and specifically, her sexy parts. Louie is put in the unlikely, awkward situation of championing a woman’s right to her own body, in the face of two angry lesbians, at least one of whom is just plain mean-spirited (and, worst of all, doesn’t believe in vaccines).

“Louie’s" surrogacy plotline touches on all of the complications of surrogacy without any of the possible upsides; it’s not an episode that is pretending to present a broad perspective on the subject, because it’s an episode of a sitcom that is really about Louie finding himself tangled up in other people’s problems. (We really don’t know how Julianne feels in this episode—just how Louie thinks she feels.) But it is a startlingly revealing episode, through that story, about not just gender, but class: It’s very easy to dehumanize another person when you’ve convinced yourself that paying them absolves you of further responsibility to them. It’s doubly easier when everyone around you is satisfied with your decision-making. Surrogacy is an expensive process that is popular in Hollywood—Jimmy Fallon, Neil Patrick Harris, Sarah Jessica Parker and Elizabeth Banks have all had children carried by surrogates. Paid surrogacy is illegal in New York state, but the law is circumvented, for those with means, by either implanting or signing papers in different states. Some queer couples champion it; some feminists are opposed to it. It’s not a cut-and-dried issue.

What “Louie” delivers most poignantly, though, is how easy it is to leave the surrogate’s voice out of the conversation at all. Surrogates are rarely named—in Hollywood, it’s the famous couple that tends to get the attention for having had a surrogate carry their child, instead of the woman who signed the other end of the contract. Alarmingly, this February 2014 New York Times article doesn’t even bother to name the surrogate until a few lines before the end, and this New York Post article from November 2013 doesn’t speak to a single surrogate mother when championing paid surrogacy. (Both outlets, interestingly, published further articles on the topic, within six months, that centered on the surrogate’s perspective. Somebody got to them.) It’s simply that extension of humanity that “Louie” and Louie and Louis C.K. seems to be talking about—both how fragile it is, especially for women who need the money, and how easy it is to forget, especially for those of us entitled enough afford it.

Shares