Between 1848, when Andrew Carnegie arrived in Pennsylvania, and 1983, when "A Nation at Risk" was published, schools had made a 180-degree turn. No longer a privilege and a respite from work, formal education had become a necessity, considered essential to individual success. What had once been a luxury for those who could afford enlightenment was, by the second half of the twentieth century, a requirement for anyone who hoped to get a job and earn a decent wage. Schools were no longer a path to cultivation and a life of the mind; they were a path to a job. And that was just in terms of the individual. Along the way, as schools became a training ground for corps of workers, they also became a means of furthering national interests. The debate about schools had become part of the debate about national power. Which brings us to the twenty-first century.

When George W. Bush announced No Child Left Behind (NCLB), his purported intention was to encourage a set of practices and institute a set of assessments that would ensure every child got the same good start at school. Implicit in that formulation was the now familiar premise that it was up to schools to close the income gap between the rich and the poor. In its most beneficent form, it could have made a powerful difference in the lives of many children. If NCLB had ensured that all kids would learn how to read and that no child would become disenchanted enough to drop out, it might have been wonderful. But that’s not how NCLB played out.

Within just a few years, teachers were rushing to make sure that each child got a higher score on the standardized tests than he or she had gotten the year before. School superintendents also felt compelled to see to it that their schools got higher scores every year. What had been promoted as a means of ensuring that all children received the fruits of our educational system became a relentless push toward improved test scores. With each year, more and more focus was on the scores themselves and less on the education the scores were intended to measure. At the national level, politicians threatened that if we didn’t educate everyone, once again our country might fall behind. The conversation was less about giving everyone access to reading, thoughtful engagement in civic life, or the pleasures of ideas, and much more about seeing to it that everyone could earn a decent wage.

Nor did that focus change much when Bush finally left office. In 2008 Barack Obama replaced George Bush in the White House and named Arne Duncan secretary of education. Many people interested in schools assumed that Obama and Duncan would shrink or dissolve NCLB, which seemed to cause only problems for parents, teachers and administrators, not to mention for children. But it has not been as simple as that. Once again money, albeit in a slightly disguised form, has shaped the conversation about what children should learn and why they should learn it.

The first thing Duncan did as secretary of education was to announce a new name for our educational agenda. Instead of leaving no child behind, we would now be in a race to the top. This meant, of course, that the United States would be racing to beat out other nations. It also meant that each child would be racing to overcome other students, getting to the finish line first. These twin motives are now embedded in almost all of the public discussion of education. When national averages of test scores are reported, they are typically presented as a table or graph in which our scores are compared to the scores of other nations. In 2009 we ranked lower on the Program for International Student Assessment than, say, China (represented by Shanghai), Finland and Estonia but higher than Latvia, Thailand and Panama. Yet, other than feeling this is a competition, it’s quite hard to know what, if anything to make of such comparisons. In the end they tell us next to nothing about the children we are trying to educate or how our educational system is (or is not) shaping them.

But the national race is only one piece of the story. Take a moment to think about what it means to frame education as a race to the top. At the simplest level, it means that someone is going to have to be at the bottom. A quick look at the way assessments are currently done in this country shows the very real consequences this has for the lives of children. Children don’t simply show that they can read, add, solve word problems, or interpret data. They must do better than other children, and better than they did the year before. Teachers, too, are rated in terms of this seemingly endless competition. Some have argued that it is good for everyone to see that education is a process, that there is always more to be learned, explored, or mastered. All of that sounds nice. But it’s not the way children (or teachers) experience the race to the top. They experience it, for the most part, as a daunting and relentless grind. It pushes children to believe that success comes only when they can outperform others and their own previous performance. An ironic symptom of this orientation is that teachers commonly talk of aiming for low scores one year so that they can show improvement in the next. The implicit belief that education rests on doing better than someone else is just one more way that a money mindset has come to shape our thoughts about schooling.

When it comes to material goods, economists have a term for this worldview: they call it positional wealth. Just as you might expect, it means that you base your sense of how rich you are on whether you are better off than the guy next door. An example will show how ubiquitous such a view has become. I spend August in the village of Sagaponack, New York, where I grew up. Though once a farm community, it is now notorious as a summer playground of the rich and famous. When I was a little girl, the men I knew drove pickup trucks and the women drove station wagons. One notable summer resident drove a green Jaguar; everyone talked about it. As the summer population rose over the years, so did the standard of cars you’d see on the road. By the time my children were born, the summer residents had taken over the island. Now Audis and Jeeps were everywhere, at least in July and August. By the time my children were teenagers, the roads were lined with Porsches and souped-up Land Rovers. Every decade brought a new level of car ostentation. But it wasn’t just the summer residents. Each decade the local population seemed to up their car game as well. The last time I visited, there was a Range Rover in every year-round resident’s driveway. If all your neighbors have a Jeep, it’s no longer enough for you to have one too; you need something just a little fancier. That is what economists means by positional wealth.

Now this principle is at play in the way we think about educational standards. It’s not enough to make sure that all children can read. They must read better, whatever that means, than children in other nations. It’s not adequate for a group of students to spell 70 percent of the words correctly. They must get a score that the money trail is 15 percent better than the students in schools one town over. I have watched the local community react when test scores are printed in our community newspaper. The first thing people talk about is which schools did better than the others and which did worse. Schools that were doing fine all along (that is, where most kids could read a page of text by the time they were in fourth grade, or where a significant proportion of the kids scored in the satisfactory range when it came to high school math) seemed pathetic if their scores had not gone up. The underlying expectation is that academic performance is always and only a matter of comparison.

Journalists, too, have played a significant role in persuading us to think of education primarily as a means to wealth. Many years ago, I called the New York Times to propose a regular series describing how teachers ply their craft and solve everyday teaching problems. The editor in charge of the education section, with whom I spoke, was enthusiastic. She said to me, “You know, we’re always so busy covering the big topics in education, we rarely get to report on teaching.” There wasn’t a hint of irony or surprise in her voice when she said this. From her perspective, what actually went on inside classrooms was more of a human-interest angle, one they could ill afford to focus on. Startled by what she said, I began keeping tabs on the big education-related stories and editorials in major newspapers. Sure enough, most of the articles were about policy (the opening and closing of charter schools, the appointment of school chancellors, the politics of school boards, and of course the debate about testing). But the most common theme was money. Journalists exhort us to fund education because by doing so we’ll raise the standard of living, close the income gap, or improve our global standing.

New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman is one of the most ardent editorial voices about education. He has argued vociferously that it is more important for children to be curious and passionate than to know a lot about specific topics. However, he frames these values in terms of their economic worth:

We know that it will be vital to have more of the “right” education than less, that you will need to develop skills that are complementary to technology rather than ones that can be easily replaced by it and that we need everyone to be innovating new products and services to employ the people who are being liberated from routine work by automation and software. The winners won’t just be those with more I.Q. It will also be those with more P.Q. (passion quotient) and C.Q. (curiosity quotient) to leverage all the new digital tools to not just find a job, but to invent one or reinvent one, and to not just learn but to relearn for a lifetime.

His ideas for revamping our schools rest for the most part on an economic argument. His point is that if our schools (and students) fall behind, it will hurt our financial security, both at an individual level and as a nation in competition with other nations.

Money has infiltrated our schools through another portal as well. Bankers and businesspeople have decided that they are the ones to improve our schools. In 2010 the educational historian Diane Ravitch did a dramatic about-face regarding educational testing and the promise of charter schools. Having been a loud and influential proponent of both (among other things, she worked in the administration of George H.W. Bush), in recent years she began to see that the national obsession with tests was in fact corrupting rather than improving the process of education in our schools. She also began to think that charter schools were sucking the lifeblood out of the public school system as well as allowing business interests to shape what was happening in classrooms. In her book "The Death and Life of the Great American School System," she documents some of the ways that people in business and finance have been wielding their influence and sidelining the input of parents and teachers. The signs of this influence are not always subtle or ephemeral either. They can be seen and heard within the halls and classrooms of schools all over the country.

One of the most insidious examples of this influence is the Edison Project, a for-profit school management company founded by Chris Whittle in the early 1990s. Whittle’s plan was to start a whole fleet of new charter schools, as well as take over existing public schools, in order to replace what he saw as flawed educational practices with superior ones. At its inception, Edison wore the mask of innovation. The schools would be lively, effective and well run. The people in charge, freed from the bureaucracy of school boards, the dulling effects of lifetime educators and the dreariness of existing school curricula, would reinvent education. Good people were involved in the project, among them Benno Schmidt, former president of Yale University. This group, seemingly well-intentioned, made articulate and compelling statements about the goals of the Edison Project. In describing the program, Schmidt said, “We also looked to the future: the sound use of state-of-the-art technology and how to organize educational spaces that free students’ minds rather than constrain them.” The scheme embraced the idea that school would liberate children to become discerning, creative and open-minded. The group’s motto clearly expressed the project’s biases: “The Edison Project believes that the creative, entrepreneurial forces so vital in other areas of our society can breathe new life into public education.” In other words, schools would be better if entrepreneurs and businesspeople took over.

The project shimmered with idealism about children and their future. The only hitch was that each of the classrooms in which these lucky children would be educated had to contain a television offering programming designed by Whittle’s company, as well as the advertisements that produced income for the company. The idealism of freeing children’s minds was anchored by a purely profit-driven motive: inculcate children with ads. Along with a sense of possibility, the scent of money wafted through the Edison plan. Here is the announcement of the first Edison schools, which opened in 1998, as described in a brief article in the New York Times:

Edison Project Gets Aid to Open New Schools

With the help of a new $25 million grant, the Edison Project, the New York company that seeks to operate public schools for a profit, announced yesterday that it would double the size of its business this fall to forty-eight schools in twenty-five cities nationwide. The unusual philanthropic boon came from a new foundation established by Donald G. and Doris Fisher, owners of The Gap clothing chain of San Francisco. The $25 million, which will be used to subsidize California school districts that want to hire the Edison Project, will create fifteen autonomous public schools, known as charter schools. Four are scheduled to open this fall: two in Ravenswood in Northern California, one in the Napa Valley, and one in West Covina, in Southern California.

As things turned out, the Edison Project largely failed. The company lost control of the vast majority of schools it had taken over. The students who had attended Edison schools did not do better on tests or complete school at a higher rate than children in other schools, as Whittle had so confidently promised. Its only visible current project is an expensive and exclusive private school in Manhattan.

Programs like the Edison Project pushed education further along the money trail. In the past few decades, money has taken on a new role. It is no longer just the intended outcome of an education or the measure of educational success. It has now become the not-so-invisible hand steering the process of education itself, deciding what children should learn and how.

In recent years, the money preoccupation has trickled upward, shaping our ideas about college as well as K–12 schooling. Not so long ago, private college was a luxury that few could afford. But in the nineteenth century, first Horace Mann and then Charles Eliot led the charge to make ability rather than heritage the price of admission to college. Though the intention was to recognize that wealth or lofty ancestry was no guarantee of intellectual ability, motivation, or academic inclination, it also came from the realization that a college degree opened doors and changed one’s future trajectory. During the same period, the introduction of excellent state university systems provided another avenue for bright and motivated adolescents with no money to get a college education. But as with K–12 education, when college changed from being a luxury for a few to a necessity for all, it redefined itself. Where once it had been a place to expand one’s horizons, read great books, get exposure to new disciplines, and learn how to participate in intellectual discourse, it now became another step toward getting a job or moving up a career ladder. The focus turned from getting a college education to getting a college degree.

Nearly every article that was published in a major newspaper between the years 2010 and 2014 about college education compared its cost to the financial benefit it might offer students in the long run. Most of the economic analyses on the “value” of college focus on a simple question: do people who complete college make more money, have more economic security, and acquire access to better jobs than people who do not complete college? It is easy to understand why the question has been framed this way. It is a lot easier to get job and income data and match those to something as unitary and concrete as a diploma than to figure out how the experiences contained within four years might change the way a person thinks, feels, or approaches the world. And yet, as so often happens, the methods used by researchers end up defining the phenomenon.

But the emphasis on education as a route to money cannot be attributed only to newspapers, researchers, business, and the government. Most individuals think of schooling in terms of money, whether they realize it or not.

I teach a lecture course on education that for many of the approximately fifty students in the class is the first time they have read research about children, and about teaching and learning. We watch videotapes of children in school. We discuss theories of education. We try to come up with curricula, think of better ways to group children, and devise innovative approaches to assessment. Some of the students get so interested in the topic that they sign up for an advanced class I offer, a seminar on teaching and learning. In that class each student spends eight hours a week working in a local classroom. They also participate in weekly seminar discussions and read articles and books about teaching and learning.

One day a young man enrolled in the seminar asked if we could meet to talk after class. When he sat down in my office, he said in a quiet voice, “I love this stuff. I can’t stop thinking about it. I know it’s what I want to spend my life doing.”

“Great!” I said. “Let’s talk about some other courses that might take you deeper into the discipline.”

“I don’t think I can,” he answered with an uncertain look on his face. “I love education. I want to teach. But I can’t do that to my parents. They worked so hard to get me here. How can I tell them that they did all of that, and I’m just going to be a teacher? I have to go into a lucrative field, something that will ensure a good career. I’m going to study computer programming.”

I have heard this sort of thing time and again. And on the face of it, it seems perfectly plausible. If sending a son or daughter to college is a stretch for a family, why shouldn’t the student do everything in his or her power to ensure that the college experience is “worth it”? The question is, what do we mean by “worth it”? Would it be less worth it for this family if their son became a teacher who woke up every day eager to go to work and went to bed each night fulfilled by what he had done than if he made lots of money but hated his work?

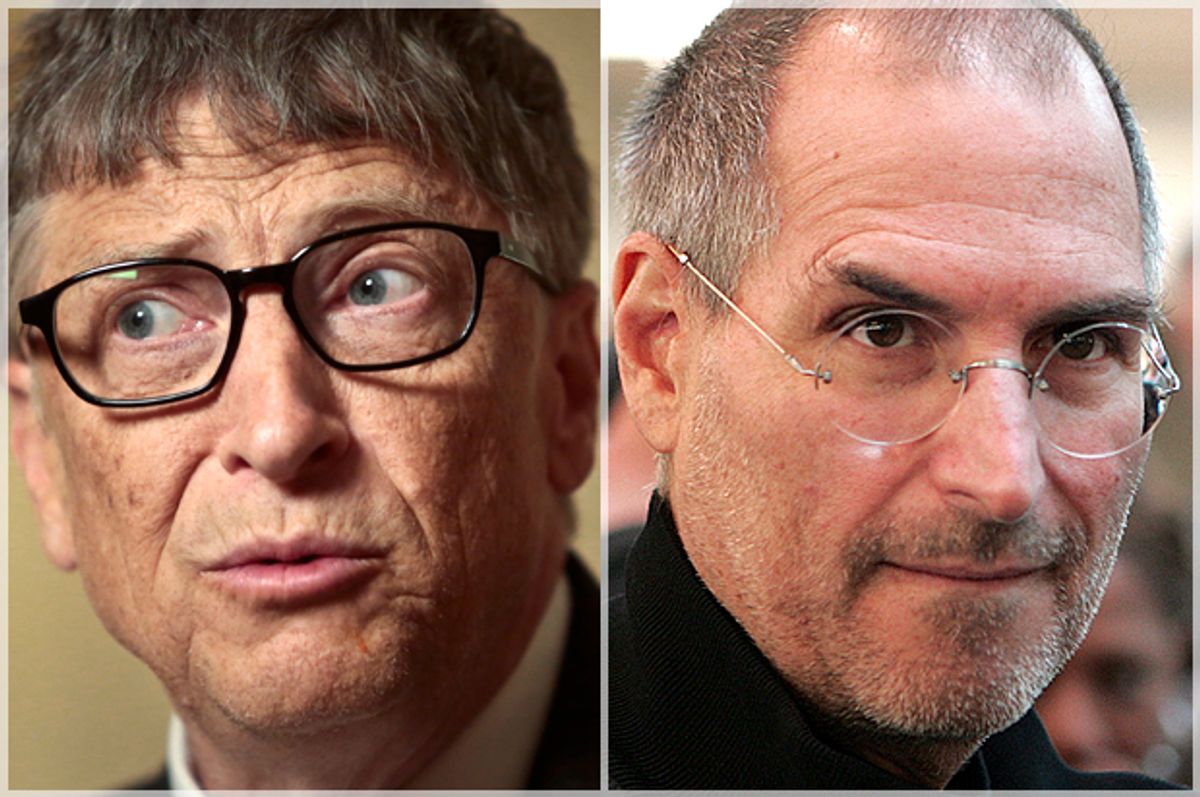

It is no longer 1848 but 2014. Imagine a small boy moving to this country today, because he and his family have run out of options in their native land. This boy is bright and has lots of energy. His family is kind and hardworking but not distinguished in any way. Perhaps they cannot read. When they arrive in this country they move to a community where others from their homeland have settled before them. But this little boy does not go straight to work, as he might have 150 years ago, the way Andrew Carnegie did. Instead this little boy goes straight to school, like virtually every other child in the United States now does. What will school provide him with, and what paths will it lead him down? What qualities will it nurture and strengthen, and what qualities will be quelled? Do our schools give children an education that will enrich their lives? Of all Carnegie’s accomplishments, the one today’s schools are most eager to steer children toward is money. And the wild irony is that the odds are overwhelmingly against any of them getting rich. Though attending school dramatically raises a child’s chance of earning a decent wage, it’s not at all clear that our schools provide any of the experiences that might lead to the other qualities that defined Carnegie: his hunger for information and ideas, his appreciation of books, his commitment to the common good, his sense of perseverance and hard work, his interest in innovation, and his gift for language. We have been learning the wrong lesson from the Andrew Carnegies, Bill Gateses, and Steve Jobses of the world. It’s not their wealth that children should aspire to. Nor is the lesson that school is unnecessary for success. Few people will become very rich. But Carnegie achieved other great things that might guide our thinking. He possessed ambition, expertise, ingenuity, thoughtfulness, erudition, and an abiding interest in community. And while it’s true he seemed to acquire these qualities in a somewhat quirky and serendipitous way, they needn’t be left to chance. They can be acquired through education. And unlike great wealth, they are prizes available to everyone.

A close look inside the classroom door suggests that in the past 150 years we have come to think, perhaps without realizing it, that the purpose of education is to make money. Though going to school hugely increases a child’s chance of earning a decent wage in adulthood, that fact need not, and should not, define our thinking about what and how children should learn. Decent wages may be a very desirable outcome of attending school. But that doesn’t mean that money should be the goal of education or the measure of its success. Of course, the skeptic might ask what harm there is in designating money as the purpose of school. As it turns out, plenty.

Excerpted from "The End of the Rainbow: How Educating for Happiness (Not Money) Would Transform Our Schools" by Susan Engel. Published by The New Press. Copyright © 2015 by Susan Engel. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares