It was 2012, a summer of fires and fracking. The hottest summer on record, they said, with Midwest cornfields burnt crisp and the whole West aflame, a summer when the last thing a card-carrying environmentalist would want to be caught dead doing was going on a nine-thousand-mile road trip through those parched lands.

I was going anyway. For almost a decade I had dreamed of getting back out West, where I had lived during my early and mid-thirties, and as it happened the summer I picked was the one when the region caught fire. Just like today drought was the word on everyone’s dry lips, and there was another phrase too—“the new normal”—that scientists applied to what was happening, the implication being that this sort of weather would be sticking around for a while. Though I hadn’t planned it that way, I would be driving out of the frying pan of my new home in North Carolina and into the fire of the American West. In Carolina, I had been studying the way hurricanes wracked the coast, but now I would be studying something different. Though my hurricane-magnet hometown’s problem was too much water, not too little, I had the sense these things were connected.

I loved the West when I lived there, finding it beautiful and inspiring in the way so many others have before me, and at the time I thought I might live there for the rest of my life. But circumstances, and jobs, led me elsewhere. It nagged me that the years were passing and I was spending them on the wrong side of the Mississippi. But I followed the region from afar, the way you might your hometown football team, and the news I heard was not good. A unique land had become less so, due to an influx of people that surpassed even the Sunbelt’s. The cries of “Drill, Baby, Drill!” might be loudest in the Dakotas, but they echoed throughout the West. The country’s great release valve suddenly seemed a place one might long to be released from. And now the fires, biblical fires, wild and unchecked, were swallowing up acreage comparable to whole eastern states.

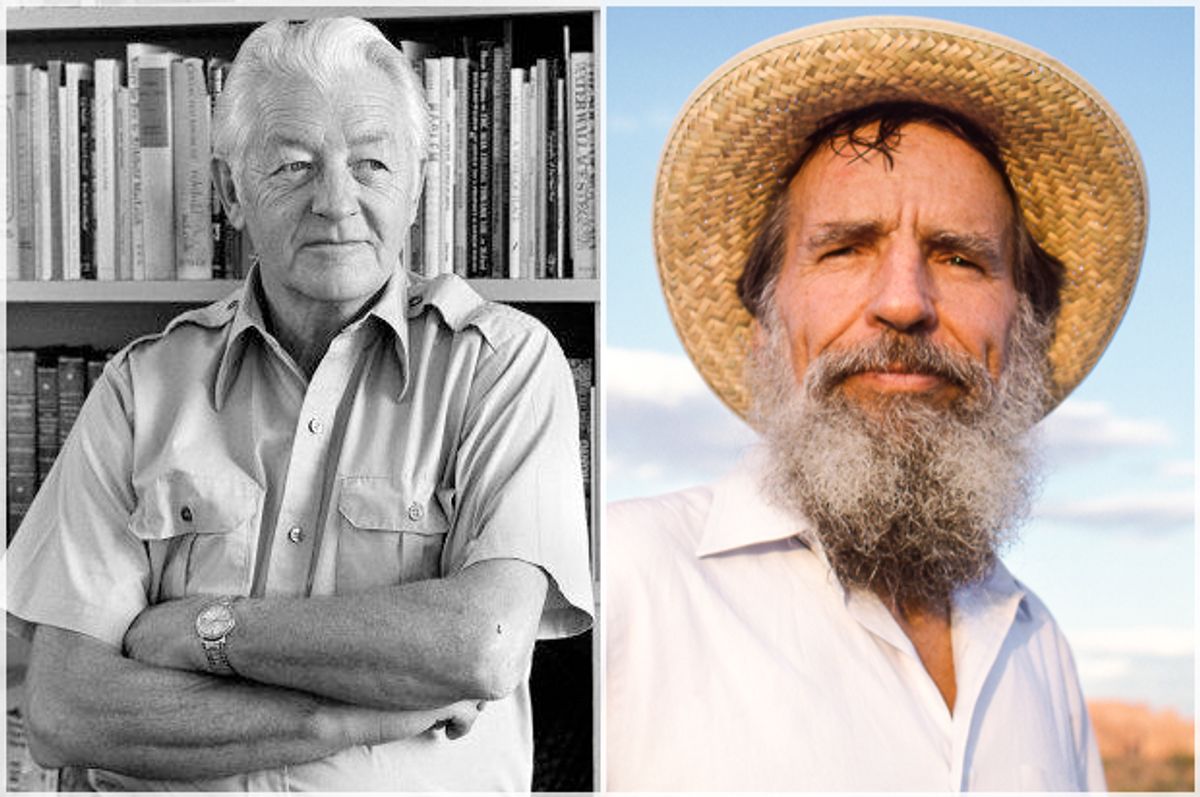

It was a summer much like this summer promises to be, with historically low snowpacks, in the Sierras this time, not the Rockies, and early fires. And though there would be no one else in the car with me, I was not traveling alone. Along with my atlases and gazetteers, I carried a box filled with a couple dozen books. Over the previous year, knowing I would be returning to the West, I had also returned to the two writers who had helped me make sense of the region. When I mentioned the names of these writers in the East, I sometimes got befuddled looks. More than once I had been asked: “Wallace Stevens? Edward Albee?” No, I would patiently explain. Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey.

It was kind of funny, really. Stegner and Abbey were both so firmly entrenched in the pantheon of writers of the American West that if the region had a literary Mount Rushmore their faces would be chiseled on it. But back east their names, as often as not, elicited puzzlement. When this happened, I would always rush to their defense. Wallace Stegner, I would explain, won the Pulitzer Prize for one novel and the National Book Award for the next, and singlehandedly corrected many of the facile myths about the American West, myths we still cling to today, earning him the role of intellectual godfather, not just of the region but of generations of environmental writers. As for Ed Abbey, I would say, he wrote a novel that sparked an entire environmental movement—have you heard of monkeywrenching or Earth first!?--and another that some consider the closest thing to a modern Walden, a book that many describe as life-changing.

What I came to believe over the course of the year, and what I suspected all along if I am honest, is that Wallace Stegner and Edward Abbey, far from being regional or outdated, have never been more relevant. What I came to believe is that, in this overheated and overcrowded world, their books can serve as guides, as surely as any gazetteer, and as maps, as surely as any atlas. It was thrilling, really, if you are allowed to use that word for reading. To see that as far back as fifty years ago Stegner and Abbey were predicting, facing, digesting, and wrestling with the problems that we now think uniquely our own.

Stegner in particular was a master of playing the child’s game of connecting the dots on a large scale. He understood that the first two dots to connect were geography and climate, and that Americans had treated a place that was desert like anything but, importing their wetland habits into the dry West. He saw the West as clearly distinct from the East due to its aridity and vulnerability to human incursion, but also because the land could be so hostile to those who tried to settle it. Many of his ideas grew directly out of his own childhood, a childhood spent migrating from the Dakotas to Washington state to a frontier homestead in Saskatchewan and then down through Montana before landing in Utah. The man driving the Stegner family’s constant movement was his father, George, whose motivation was one well known in the West: he was looking to strike it rich. His father embodied a type of Western character that Stegner would write about all his life, the “boomer” who searched for the quick strike whether in oil, gold, land, or tourism. In contrast to the boomer, Stegner idealized his mother as a “sticker,” one who tried to settle, learn a place, and commit to it. From these latter qualities the writer built the platform from which he both wrote and preached: commitment to place, respect for wild and human communities, responsibility for and to the land. Having grown up with a man who was the classic Western “rugged individualist,” Stegner spent a lifetime debunking that myth. And having spent a good deal of his youth in Utah, he was one of the few to see in Mormon culture an overlooked quality that made them one of the only communities to thrive in the West. That quality, surprisingly, was sharing. It’s easy to laugh and note that this notion can get a little twisted when applied to, say, marriage, but it turned out that it worked quite well when it came to sustaining agriculture in what was, despite the insistence of many boomers, a desert. Stegner understood, and put forcefully, the fact that the West’s greatest resource wasn’t gold or oil or uranium or even land, but water. In 1920 drought drove his family from Saskatchewan, the place where the young Wally felt most at home, and he saw in his own past his region’s future. He would have been saddened, but not surprised, by this summer’s conflagrations. Nor would he be surprised that a dry place has become drier.

Abbey, on the other hand, had a taste for controversy and crude jokes and could sometimes be as subtle as a whoopee cushion. But he could describe nature like no one else. If he was often tagged with that much overused encomium, “a modern Thoreau,” there was some truth to it. Thoreau said he spoke loudly because those he addressed were hard of hearing; if he crowed like a chanticleer, it was to rouse people. What stirs people? What wakes them up? These were questions that concerned Thoreau, and that concerned Abbey, too. Perhaps the greatest resemblance is between the shapely shapelessness of each man’s greatest books. Abbey’s Desert Solitaire tells the story of a year in the wild in the tradition of Walden, recounting the time Abbey spent as a ranger at Arches National Park in Utah. The book is full of bliss and rage, evoking visceral responses in its readers. It had the ability, as the writer David Quammen put it in his appreciation after Abbey’s death, to “change lives.” It could make a salesman in Ohio buy hiking boots and head west. It was a book about spending a year alone in a government trailer out in a place full of giant twisting red rocks, a book about the rawness of the desert, a book about paradise found and paradise threatened, a book about wedging downward through the bullshit of modern, industrial life in an attempt to find the hard rock of reality. And it was a book largely about Abbey, or the Abbey character, through whom the reader vicariously luxuriates, lounges, rages, and delights. Built in part out of his journals, the Abbey on the pages of the book excited the imaginations of thousands of readers.

Even at its silliest, Abbey’s work, like Stegner’s, never neglected that element that had gone missing in the writing of so many of their East Coast contemporaries: wilderness. And during the ‘70s, when plotlessness and metafiction ran amok, the work of both Stegner and Abbey was political in the broadest sense of the word. Here is what Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt said about Stegner’s biography of John Wesley Powell:

When I first read Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, shortly after it was published in 1954, it was as though someone had thrown a rock through the window. Stegner showed us the limitations of aridity and the need for human institutions to respond in a cooperative way. He provided me in that moment with a way of thinking about the American West, the importance of finding true partnership between human beings and the land.

Both Stegner and Abbey would eventually be described by their biographers as “reluctant environmentalists,” the reluctant part due mostly to their commitment to writing, but reluctant or not, they would become in very distinct ways two of the most effective environmental fighters of the twentieth century. And in their passion for the fight they showed their core kinship, even as their manner of fighting revealed wide personal and stylistic differences. While Stegner’s political thinking was more sophisticated and restrained, Abbey’s words had a rare attribute: they made people act. Monkeywrenching, or environmental sabotage, has recently been lumped together with terrorism, but Abbey could make it seem glorious. After finishing a chapter or two, readers would want to join his band of merry men, fighting the despoiling of the West by cutting down billboards and pulling up surveyors’ stakes and pouring sugar into the gas tanks of bulldozers, all of this providing a rare example of true literary influence at work.

At core one man believed in culture while the other, in a very deep and ingrained sense, was counter-cultural. But for all their differences they shared common ground. While neither liked to be considered regional, their region deeply concerned them. “The geography of hope” was how Stegner described the western landscape, but as the years passed he felt a growing sense of hopelessness. Abbey also grew more frustrated, and angrier, as he saw the place he loved being despoiled. He came to believe that the proponents of growth were insane men who thought themselves normal but who didn’t understand that growth for growth’s sake was really the rapacious “ideology of the cancer cell.” He wrote: “They would never understand that an economic system that can only expand or expire must be false to all that is human.” Both men fought until the end of their lives to preserve the land they loved, but for both it was an increasingly desperate fight.

Would they be surprised at what the West has become? I doubt it. The region was already heading the way it has gone and they were among the first to point it out. True, they couldn’t have known the full extent of man’s capacity to alter climate and make the region an even hotter and drier place. But today’s West is a kind of fulfillment of their darker prophecies, and if they died too soon to know the role that climate change would play, they were acutely aware of the way that the West’s aridity made it more vulnerable than the rest of the country. Indeed, drought has helped aid massive fires and bark beetle infestations that have already destroyed close to twenty percent of the region’s trees. As for the boom in fracking and other mining, it would not have surprised them one whit. The West had always been a resource colony, there to be exploited.

That is the West I was headed toward. A place of startling beauty and jaw-dropping sights. But also a place in a world of trouble. It seems to me that anyone who cares to really think about the world today has to hold both of these things in mind, to remember to see the beauty, and to still take joy in that beauty, but not shy away from the hard and often ugly reality. And it seems to me that Stegner and Abbey, who after all walked this same path before us, are well suited to help guide us in this difficult task.

Robert Frost, whom Stegner got to know at Bread Loaf, wrote in “The Oven Bird”: “The question that he frames in all but words/is what to make of a diminished thing?”

That is my question too.

David Gessner is the author of nine books, including "All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West," from which this is adapted.

Shares