Imagine what would happen if we passed a law that required every elected representative in the U.S. to take a phone call from a minimum of 10 constituents a day (and I mean individual constituents, not lobbyists and interest groups). Under this law, representatives would also be evaluated by Likert scale surveys on how well they meet the needs of their constituent callers. Anytime survey scores slip below a certain numerical threshold of acceptability, the elected official is fired from office, regardless of the results of democratic election or the prescriptions of the state or federal constitutions. By such standards of evaluation, how many of today’s representatives would still have a job?

I ask because the Iowa legislature has recently introduced a bill for institutions of higher education in Iowa that mandates that professors whose student evaluations dip below a certain, government-set threshold be terminated, “regardless of tenure status or contract.” Further, the bill calls for the bottom five professors above the threshold on the scoring scale to be publicly shamed by having their names and scores published, after which point “the student body shall be offered the opportunity to vote on the question of whether any of the five professors will be retained as employees of the institution.” And there you have it, at last: the inevitable convergence of assessment strategies for higher education and "Survivor."

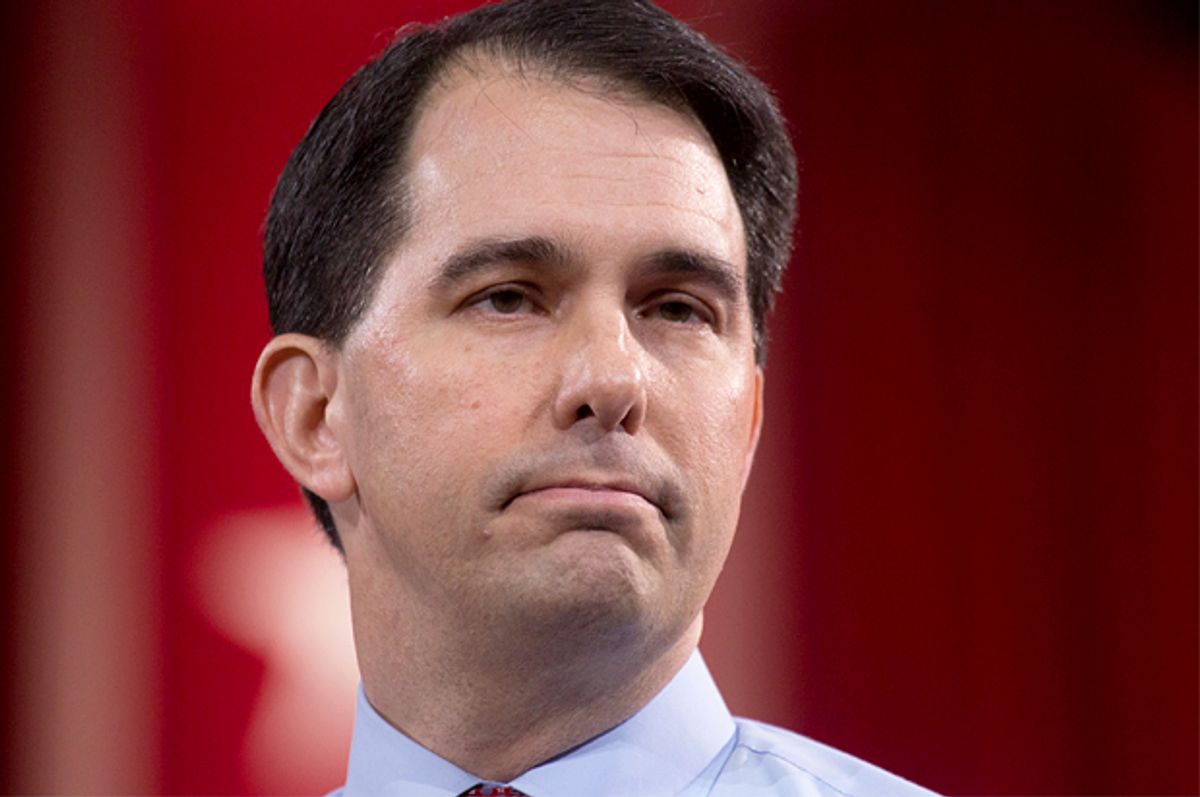

The Iowa bill follows similar legislation in North Carolina, a bill to “improve professor quality” by mandating that professors in the North Carolina public university system teach four courses each semester. The rationale of the “improve professor quality” bill: if professors at research-intensive universities are required to teach at least twice as many classes as they do now, their teaching will improve. Because, as everyone in any job can imagine, we’d all do our jobs much better if we were required to do twice the work in the same amount of time for the same amount of money? Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker is taking this curious illogic yet further by proposing in his state that professors need to be “teaching more classes and doing more work," only he plans to compensate them by cutting the University of Wisconsin system budget by $300 million over the next two years.

The reason I don’t seriously advocate for similar impositions on elected representatives, as in my opening thought experiment, is because I’ve never spent a second of my life as an elected representative. I have ideas about how representation in the U.S. might be improved, but I certainly wouldn’t propose to implement those ideas without getting a firm understanding of what the job of representation entails, preferably from a range of experienced elected representatives, and from the vast body of research on democratic and electoral reform. If only our elected officials in conservative strongholds like Iowa, North Carolina and Wisconsin were capable of the critical thinking required to understand that they’re meddling in something of which they have little knowledge and less experience.

The stereotypical professor is usually a lazy and irreverent misanthrope with a penchant for booze (Dennis Quaid in "Smart People"), a brooding obsessive (Russell Crowe in "The Next Three Days"), an incompetent nitwit (Luke Wilson in "Tenure"), and occasionally a murderous villain (James Purefoy in "The Following"). But research shows that the average professor works 61 hours per week, hardly enough time to drink on the job, plan a jailbreak, or develop a murderous cult following on weekends. If we actually evaluated our elected officials based on stereotypes of their work, rather than the reality of the demands on their time and energy, I wonder once more: how many of them would get to keep their jobs?

The greatest irony of all in these stories about clueless legislators dictating terms of assessment for teaching and research to expert professionals, however, is that elected officials are perhaps the one kind of professional for whom it’s reasonable to judge primarily (if not exclusively) by accountability to their constituency. Since democracy—unlike teaching and learning—is foremost about representation, locating true authority in the voters above the representatives, our elected officials should spend less time worrying about how students rate professors, and more time thinking about how we rate their service.

In the college classroom, we most certainly care what students have to say about how we teach, mentor, and prepare them. I read every word of every student evaluation I get each semester, and I reread it all again before I step into the classroom the next semester. As you might imagine, much of student feedback is helpful; some of it is misguided. Along with being observed by experienced faculty peers, this is one of the ways I improve my “teacher quality” on a semesterly basis. But like every professor (and countless students, too), I also know that there’s an obvious conflict of interest at hand if and when students have direct power to oust professors. We already have the “I deserved an A” conversation all the time. Do we want to have that conversation with a job and a career on the line every time? Is this what Iowa legislators mean by professor “effectiveness”: converting students into paying customers who are always right, even when they’re wrong?

To put it simply, it would be mad to propose to improve the quality of brain surgery by asking brain surgeons to double their patient load. It would be mad to propose to improve the quality of police work by asking police officers to double their shifts. And it would compound this madness to propose such things while also slashing operating budgets and subjecting practitioners to termination if they don’t set aside their experience and expertise and cater strictly to the desires of the people they’re trying to assist, the people who go to the surgeon or the police not because they already know how brain surgery or police work is done, and have the resources to do it themselves, but because they don’t; because they need an expert to help them out.

If, as in surgery and police work, we want real quality in higher education, we need to support and listen to the experts who do the work of teaching and research everyday. Putting words like “effectiveness” and “quality” in the title your bill won’t fool anyone but those who, based on stereotypes, already despise what education stands for (until the next time they read a challenging book or article, pop an aspirin, or cross a bridge).

This is the real motive behind the conservative legislative agenda when it comes to higher education: to use buzzwords like “quality” and “effectiveness” to mask measures that make it more difficult for professors to supply quality education to our students—the future of our democracy and economy—and to conduct research effectively. “Quality,” “efficiency” and “improvement” have long been corporate euphemisms for slashing jobs and burning institutions to the ground. An educated populace with access to both the rich history and the cutting edge of knowledge is the scariest thing for those who are politically invested in maintaining a docile and contingent work force, a fear of social change, and a revisionist history of “efficient” and “creative” destruction of public goods.

Shares