“Religion” is a big word, maybe too big. It is one of those words, like “artist,” capacious enough to denote both a thing and its near opposite. Religion is the Tao Te Ching and Dianetics. Augustine and Koresh. Hillel and Kahane, Rumi and bin Laden.

So why does the public conversation around religion often seem so cramped and stunted? Why is it dominated by people who are fond of reducing it to thumbs-up, thumbs-down propositions that leave no room for the way most people think about it?

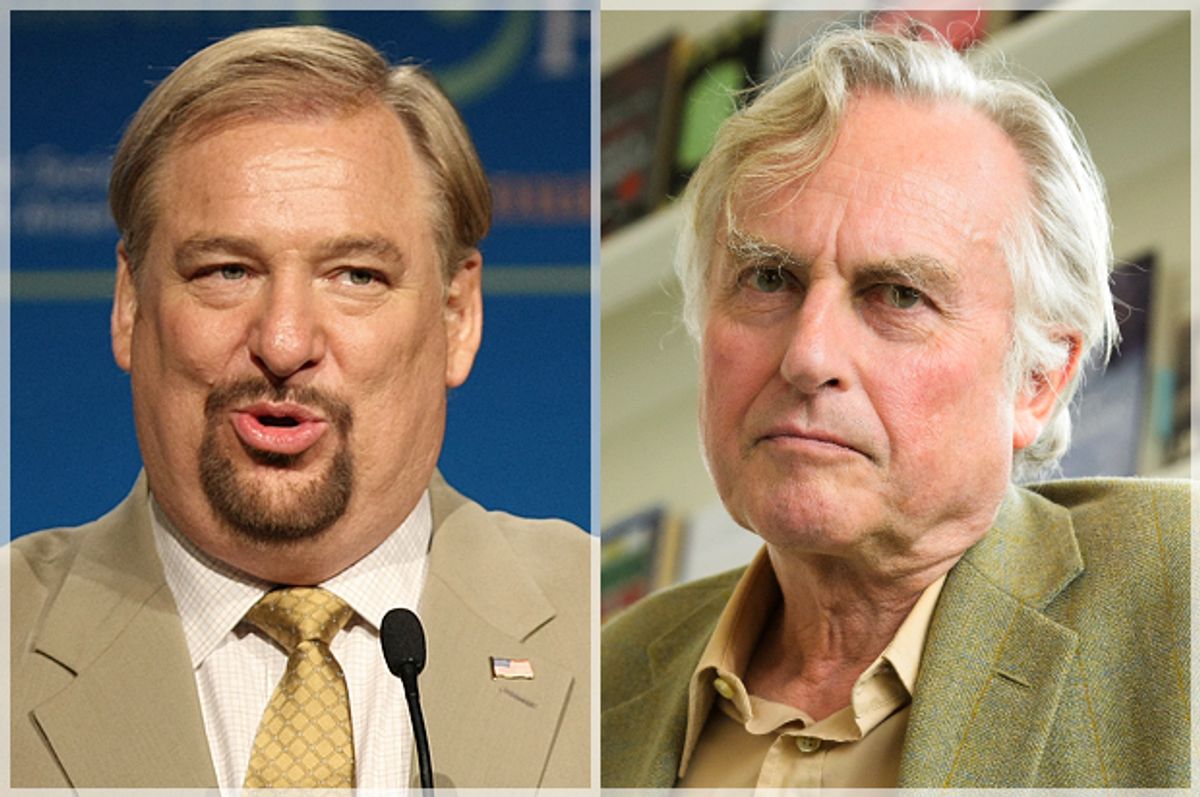

“New Atheists,” such as Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins, and religious TV personalities like Pastor Rick Warren and Rabbi Shmuley Boteach like their conversations tidy. They are big fans of pithy, aphoristic wisdom, and are united in their contempt for those who can’t fit their thoughts about God onto a book jacket. After years of debating each other in person and in print, they have developed the glib instincts and interdependence of perfect comic foils, and a telling habit of inadvertently making each other’s cases.

Richard Dawkins likes to complain that, “religion teaches us to be satisfied with answers which are not really answers at all.” To which the Dalai Lama might respond, “Why, yes, Mr. Dawkins. Yes, it does.” Authentic religion isn’t all that interested in answers--not the kind Dawkins is talking about anyway--but he and his fellow atheists persist in submitting questions to it like, “Why can't we see God?” and then gloating at the lack of response.

Dawkins’ preemptive, broad-brush statement about what “religion” teaches us is typical of both New Atheist and TV Preacher rhetoric, in that it reduces the vast and varied expanse of religion to either a tiny Jonestown, stranded in a jungle of primitive ignorance, or a brain-dead, shining city on a hill. Christopher Hitchens wrote, "To 'choose' dogma and faith over doubt and experience is to throw out the ripening vintage and to reach greedily for the Kool-Aid." True enough. And here’s a short list of extremely religious people who would have said “Amen” to that: Epicurus, Aquinas, Kierkegaard, Spinoza, Descartes, Dante, Hillel, Maimonides, St. Paul, Lao Tzu, Buddha, Mohammed and Jesus.

It never seems to occur to the New Atheists or the religious zealots that, while many practitioners of religion might be in it for the ignorance, many others are after the sublime dissatisfaction they experience as they try to understand the world, and that religion makes sacred. Many might not even think of their practices as religious. The difference between a morning spent in contemplation of Leonard Cohen's "The Stranger Song" and one meditating on the Book of Hebrews' call to love the stranger is a very fine one, but both involve consecrating art and ritualizing philosophy, both grapple with profound questions on an experiential level, and are typically ignored by the most passionate defenders and attackers of faith.

What would happen if we had another word for this kind of humanistic, fluid and volatile religion? Would we jog the imaginations of scientists and clerics if we gave a different name to the way many, maybe even most, people interact with mystery? As long as the zealots get to define the terms, the conversation about religion will be a narrow, self-serving pretense.

The New Atheists' favorite rhetorical strategy is to assign the very real faults of pseudo-religion to authentic traditions that are committed to the very opposite of those flaws, and to accuse those traditions of failing at an endeavor they are not engaged in: the answering of scientific questions. The strategy is designed to reinforce the idea that religion is a reaction to the limits of intelligence, rather than what it is: a reaction to the limits of consciousness.

“Authentic religion” might sound like a problematic notion. But while the many, many hucksters of religion, the peddlers of “Prosperity Gospels,” “Secrets” and childhood martyrdom, are cynical purveyors of cherry-picked, bastardized, egocentric dogma, the great, doctrine-averse, deeply doubtful religious thinkers of history were not. They in fact emphasized transcendence of the ego as the key to enlightenment.

Authentic religion doesn’t ask us to follow Seven Easy Steps to Nirvana, or crunch numbers to comprehend the Tao. It invites us to encounter the infinite, to engage with it. It is not the opposite of scientific inquiry, but it wants us to place our attempts at a physical understanding of the universe in a broader context by acknowledging the narrow scope of our perception. It asks of us the courage to live consciously, to notice all that we don’t see, and muster the imagination to integrate that vision into the human enterprise.

The New Atheists see no distinction between those who find comfort in religious answers and those who grapple with religious questions. They refuse to define religion as anything other than the pseudo-religion favored by TV evangelists and radical ayatollahs, by those who see things in as limited a way as they do. And they insist that religion do the work of science, paying no respect to either.

Pseudo-science and pseudo-religion are easy targets because they’re easy, and appeal to the lazy. Authentic religion and genuine science are hard. They require attention, honesty, intellectual and emotional stamina. The mushy precepts of “good news” deliverers and revivalists; the anti-intellectual, anti-sexual coercion of fire-breathing rabbis and theocrats are designed to deaden the spirit, to conjure enough sentimentalized “wonder” to stupefy, enough ominous mystery to frighten.

The religionists of the world take advantage of the close psychic proximity of awe and terror to blur the distinctions between them and cultivate fear of the unknown in the hearts of their disciples. Their practices are worthy of criticism, but they have as much to do with sincere religious exploration as the Tea Party platform does with genuine personal liberty.

The premise of authentic religious practice, on the other hand, is that mystery is not to be feared but wrestled with, as Jacob wrestled with the angel. It’s not enough to be merely in awe of the universe; the question all the great religions ask is what are you going to do with your awe? One of the many valid responses to this question, along with traditional religious answers like, “do unto others as I would have done unto me,” “love the stranger,” “let go of desire,” and “heal the world” is: “Do science. Extend knowledge. Measure great distances, observe small particles.” I don’t know of a serious religious thinker who isn’t deeply interested in that kind of searching, and in the many ways it complements religion. But I also don’t know of any who think that it is religion.

New Atheists and religionists treat religious texts with equal condescension, one reading literally, so as to frame the “God debate” as one between reason and superstition, and the other interpreting freely, smoothing over embarrassing contradictions so as to frame it as an argument between the Word of God and the complaints of man.

This kind of selective literalness is used by both sides of the debate to keep the conversation tame and orderly, to keep it from getting out of their hands. It’s the religious equivalent of “strict constructionist” arguments about the Constitution, and just as cynical.

Both sides sneer at what we might call the “living document” approach to sacred texts, a style they sometimes call “cafeteria” or “DIY” religion, in which people cobble together their own spiritual practice by picking (or inventing) religious customs that have particular meaning to them. Staunch defenders of religious doctrine, like Catholic League President Bill Donahue (he of the camel-through-a-needle, self-paid salary of $400,000 and vehement support for the death penalty) see contemporary, cafeteria religion as a product of a narcissistic age, but of course all religions are “DIY” and always have been.

Orthodox Jews in Los Angeles don’t wear fur hats in imitation of Abraham or Noah but of their great-grandparents in 19th century Minsk and Dubrovnik. Catholic priests were tacitly allowed to marry until the mid 18th century. Most of the world’s Muslim women no longer wear the veil. Religious practices are as much a product of their time, place and political circumstances as anything else, and religious texts can be read as histories like the rings of a tree. They tell stories of human inventiveness in the service of living a meaningful life.

Authentic, humanistic religion, like art, is in the necessary—and necessarily futile—business of perceiving the gulfs between realities, large and small. Most of us who don’t have a Hubble Telescope handy do this by delighting in the tiny chasms closer to home, between one mind and another, one pillow and the next.

The philosophies at the heart of the great traditions emphasize the importance of empathy above all other human values, but the people at the extremes of the God debate don’t seem to know that. Maybe that’s why they seem so humorless. They seem impervious to the essentially comic nature of the frustrating, human bind we’re all in. The fundamentalists cultivate something like a sulky teenager’s romanticized notion of love, and the atheists a grumpy old bugger’s lack of belief in such nonsense. But love of the Divine isn’t a feeling, or a belief, it’s something you make yourself available to. It’s an understanding that we are being asked, not to desperately fill the infinite spaces between each other, but to let what’s in that space fill us--with laughter, and humility, and wonder, and love.

Shares