Ten days after the [2008] election, Rob Reiner and Michele Singer Reiner invited Chad Griffin to lunch at the Polo Lounge in the Beverly Hills Hotel. Inevitably, the conversation turned to Prop 8. Outraged that the right to marry had been withdrawn by a popular vote, the group discussed the possibility of a federal lawsuit.

Because Prop 8 was now enshrined in the state constitution, advocates of same-sex marriage had no substantive judicial challenges left under state law. The only viable claims were procedural ones, like Strauss, which contested whether Prop 8 had been enacted in the proper manner. Advocates of same-sex marriage could always bring a federal challenge to Prop 8, given that federal law trumps state law when the two conflict. But here lay dragons. Unlike a state constitutional challenge, a federal constitutional challenge could ascend to the United States Supreme Court. Any decision there would bind the entire nation, either way. A win could permit same-sex couples to marry in all fifty states. A loss could foreclose a fifty-state solution for the foreseeable future.

After Griffin left, an acquaintance of the Reiners, Kate Moulene, stopped by the table. Later that afternoon, Moulene phoned Michele Reiner to suggest that they speak to her former brother-in-law, the lawyer Ted Olson. “Ted Olson?” Michele Reiner exclaimed. “Why on earth would I want to talk to him?”

Olson, who was sixty-eight when Prop 8 passed, is a central figure in the conservative establishment. He is still most famous for winning Bush v. Gore, the blockbuster 2000 case that ensconced George W. Bush in the Oval Office. Olson had become active in the Republican Party as a student in California in the 1960s, valuing small government and individual liberty. He was one of a few law students at the ultra-liberal University of California at Berkeley to support Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential bid.

Many of Olson’s causes over the years had set him at odds with progressive communities. In Reagan’s Justice Department, Olson worked to end race-based affirmative action in federal contracting. On behalf of the state of Virginia, he argued against allowing women into the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), losing that case in the Supreme Court in 1996. As President George W. Bush’s solicitor general, Olson pressed for broad interpretations of the executive branch’s wartime powers. Indeed, Olson had been approached about defending Prop 8 in the California Supreme Court after he returned to the multinational law firm of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher. When he declined, fellow conservative eminence Kenneth Starr got the job. Like Justice Clarence Thomas and former Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, Starr was a close friend of Olson’s. Legal reporter Jeffrey Toobin described Olson and his wife Barbara—who perished on one of the hijacked airplanes on 9/11— as the “first couple of the legal conservative world.” “If Hillary Clinton’s vast right-wing conspiracy had a headquarters,” Toobin wrote in 2008, “it was their estate in Great Falls, Virginia.”

Wherever one stands politically, it is next to impossible to dislike Olson. He has a canine quality, with his slightly jowly face and matted sandy hair. Debating him is like debating a golden retriever with a genius IQ. Time and again, liberal participants in the trial carried this refrain. The plaintiffs’ political science expert Gary Segura took the stand in Perry on January 21, 2010, the day Olson won the Citizens United case—a huge blow to many progressives in its invalidation of significant restrictions on what could be spent in political campaigns. Segura recalled: “Other people on his team were trying to explain why the case was correctly decided. And I said, ‘Get away from me, I teach this stuff at Stanford; you’ve just destroyed democracy.’ But Ted? Ted is a hell of a guy.”

Despite his conservative reputation, Olson was no stranger to gay rights. While working in the Reagan Justice Department, he wrote a legal opinion maintaining that a prosecutor could not be denied a promotion just because he was gay. During the Bush administration, Olson slammed a proposed amendment to the federal Constitution that would have banned same-sex marriage. Olson also believed religious convictions could not justify governmental restrictions on civil marriage. Having grown up and practiced law in California, Olson was shocked when the voters passed Prop 8.

Olson finalized his participation in December 2008 at the Reiners’ Los Angeles home, where he assured the assembled group of elated but confused progressives that he would not “just be some hired gun.” Olson later acknowledged that in certain progressive circles, he was known as “the devil.” “Now,” he observed, “I’m the devil to a different group of people.” He was. Bork declared he could not speak to Olson on this topic. Ed Whelan, a prominent conservative lawyer who would follow the case closely, predicted on CNN that Olson would never recover his conservative reputation, given that the lawsuit was “a betrayal of everything that Ted Olson has purported to stand for.” Apparently, Olson’s support for the case was like the thirteenth chime of the clock that calls all that preceded it into question.

Olson had neither the time nor the temperament to let the naysayers get to him. The belief that other federal lawsuits would soon be filed imbued Griffin and Olson with urgency. By early spring, the Gibson Dunn Prop 8 team had members in offices in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Washington, DC. By April, the legal team had vetted the issues from all angles and concluded it could win at the US Supreme Court. In Olson’s words, the key to Supreme Court litigation was the ability to “count to five.” Olson believed he could find that majority on the nine-member Court.

But which five? In April 2009, the Supreme Court had a bloc of four solid conservatives: Chief Justice John Roberts, Justice Samuel Alito, Justice Antonin Scalia, and Justice Clarence Thomas. Most pundits assumed all four would vote against marriage equality. The Court had an equally solid bloc of four liberals: Justice Stephen Breyer, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Justice David Souter, and Justice John Paul Stevens. Court watchers predicted Justice Souter and Justice Stevens would retire before the case reached the Court. However, they correctly assumed President Obama would replace these liberal jurists with like-minded colleagues. In 2009, Justice Sonia Sotomayor replaced Justice Souter; in 2010, Justice Elena Kagan replaced Justice Stevens. Although many commentators presumed the four liberals would vote for marriage equality, others challenged that premise—not because they thought the liberal justices were ideologically opposed to same-sex marriage but because those justices might be wary of moving too far ahead of public opinion. In particular, Justice Ginsburg had expressed concern over the years that Roe v. Wade’s “heavy-handed” intervention had triggered a backlash that had endangered the right to abortion. (Ginsburg would just have struck down the draconian Texas law, letting the debate about less-restrictive abortion regulations percolate.) Some considered her frequent invocation of this point to be a worrisome omen for Perry.

The Gibson Dunn team’s greatest cause for optimism lay in two pro-gay majority decisions penned by Justice Kennedy. In the 1996 case of Romer v. Evans, the Supreme Court struck down an amendment to the Colorado Constitution under the federal Equal Protection Clause. Amendment 2 represented the successful attempt of anti-gay groups to wash out the pro-gay laws in three cities—Denver, Boulder, and Aspen—and to bar pro-gay measures moving forward. The amendment’s impact was harsh and far-reaching. Under Amendment 2, neither the state legislature nor any local government could enact a policy protecting gay men, lesbians, or bisexuals from discrimination in any context. They could, however, enact such policies protecting heterosexuals. So after the amendment passed, a landlord in Aspen could post a sign saying no gays allowed in his yard. Yet he was arguably still barred from posting a sign saying no straights allowed. At oral argument, Justice Ginsburg asked the lawyer for Colorado if he could think of another law of this kind in the nation’s history. The lawyer acknowledged that the law was “unusual.”

Writing for a six-member majority of the Court, Justice Kennedy struck down Amendment 2, deeming it “unprecedented in our jurisprudence.” He found the measure to be “at once too narrow and too broad,” because “it identifies persons by a single trait and then denies them protection across the board.” Such laws, Kennedy wrote, “raise the inevitable inference that the disadvantage imposed is born of animosity toward the class of persons affected.” Kennedy observed that a 1973 precedent established that “bare . . . desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot constitute a legitimate governmental interest.”

Kennedy’s categorization of anti-gay sentiment marked a major advance for gay rights. Moral objections to homosexuality had long been used to justify laws burdening gays and lesbians. In the same year that the Court handed down Romer, a report from the House of Representatives justified DOMA as an appropriate expression of “moral disapproval” of homosexuality. Justice Kennedy’s opinion reframed disapprobation of gay people as “animus,” and held that such animus was not a constitutionally legitimate basis for law. In doing so, it adopted an analysis comparable to the Court’s approach in cases protecting the rights of other minorities, such as individuals with disabilities. It gave gays and lesbians a newfound dignity in constitutional jurisprudence.

Still, legal analysts warned against overestimating the pro-gay dimensions of Romer. Kennedy stressed that the harms the Colorado amendment inflicted on gays and lesbians were “broad and undifferentiated,” a universal pox. Barring Colorado from making gay individuals “strangers to our laws” did not prevent any state from saddling gays with lesser harms. Adhering to that view, state supreme courts in liberal states like Washington and Maryland read Romer narrowly in upholding bans on same-sex marriage.

Olson’s optimism about Justice Kennedy’s vote stemmed above all from the epochal 2003 case of Lawrence v. Texas, often touted as the Brown v. Board of Education of the gay-rights movement. In this case, the Court considered the constitutionality of state laws that criminalized same-sex sodomy (even if that activity occurred between consenting adults in the privacy of the home). In Lawrence, Justice Kennedy again wrote a stirring majority opinion striking down those laws. Along the way, he overruled Bowers v. Hardwick. In the infamous 1986 Bowers decision, the Court had rejected the argument that the Constitution’s right to privacy protected “homosexual sodomy” as “at best, facetious.” In Lawrence, Justice Kennedy reiterated that moral objections, standing alone, could not justify such restrictions on individual liberty.

While Kennedy noted that the case did not raise—and therefore did not decide—whether same-sex relationships were entitled to “formal recognition,” his colleague Justice Scalia was having none of it. In his dissent, Justice Scalia asked: “If moral disapprobation of homosexual conduct is ‘no legitimate state interest’ . . . what justification could there possibly be for denying the benefits of marriage to homosexual couples exercising the liberty protected by the Constitution? Surely not the encouragement of procreation, since the sterile and the elderly are allowed to marry.” He concluded: “This case ‘does not involve’ the issue of homosexual marriage only if one entertains the belief that principle and logic have nothing to do with the decisions of this Court.”

Although many opponents of same-sex marriage doubtless grimaced over Justice Scalia’s analysis, many disagreed with Scalia, distinguishing the freedom from governmental condemnation from the freedom to secure governmental affirmation. As the main opinion of the New York high court said in denying same-sex couples the right to marry under the state constitution in 2006: “Plaintiffs here do not, as the petitioners in Lawrence did, seek protection against state intrusion on intimate, private activity. They seek from the courts access to a state-conferred benefit.”

So while Romer and Lawrence were both pro-gay decisions written by Justice Kennedy, and while Kennedy was a vital vote, it did not follow that Kennedy would be the fifth vote to invalidate Prop 8.

* * *

Whether or not Olson was reading Kennedy correctly, the endeavor had reached the point of no return. In April 2009, Griffin’s team officially incorporated the American Foundation for Equal Rights (AFER). As gay-rights magazine The Advocate noted, “The foundation’s website is nearly indistinguishable from, say, the Tea Party movement’s site: no rainbow hues, no equality symbols, just American flags—something Griffin was adamant about. ‘That’s my flag too. That’s the LGBT community’s flag as much as any other group’s.’ ”

In addition to a public-relations function, AFER performed a major fund-raising role. While Gibson Dunn donated the first $100,000 of its services, it required flat fees thereafter. In one four-week period in 2009, AFER raised millions of dollars from fewer than a dozen donors—“gay and straight,” as Griffin emphasized. The total fees ended up exceeding $6 million—a price tag that has generated some controversy, given that many lawyers argue significant public-interest cases for free. Griffin explained early in the litigation that he had sought “the lawyers Microsoft is going to want, not the lawyers who are going to do it pro bono.” But the need for quality representation does not fully explain the steep price. Paul Smith of the law firm Jenner & Block successfully argued Lawrence v. Texas pro bono before the Supreme Court in 2003. Ten years later, Robbie Kaplan of Paul Weiss brought United States v. Windsor, a case challenging the federal Defense of Marriage Act, without, in her words, “billing a penny.” And of course many of the LGBT public-interest organizations also have exceptional lawyers, who have litigated the movement’s most significant victories without charge.

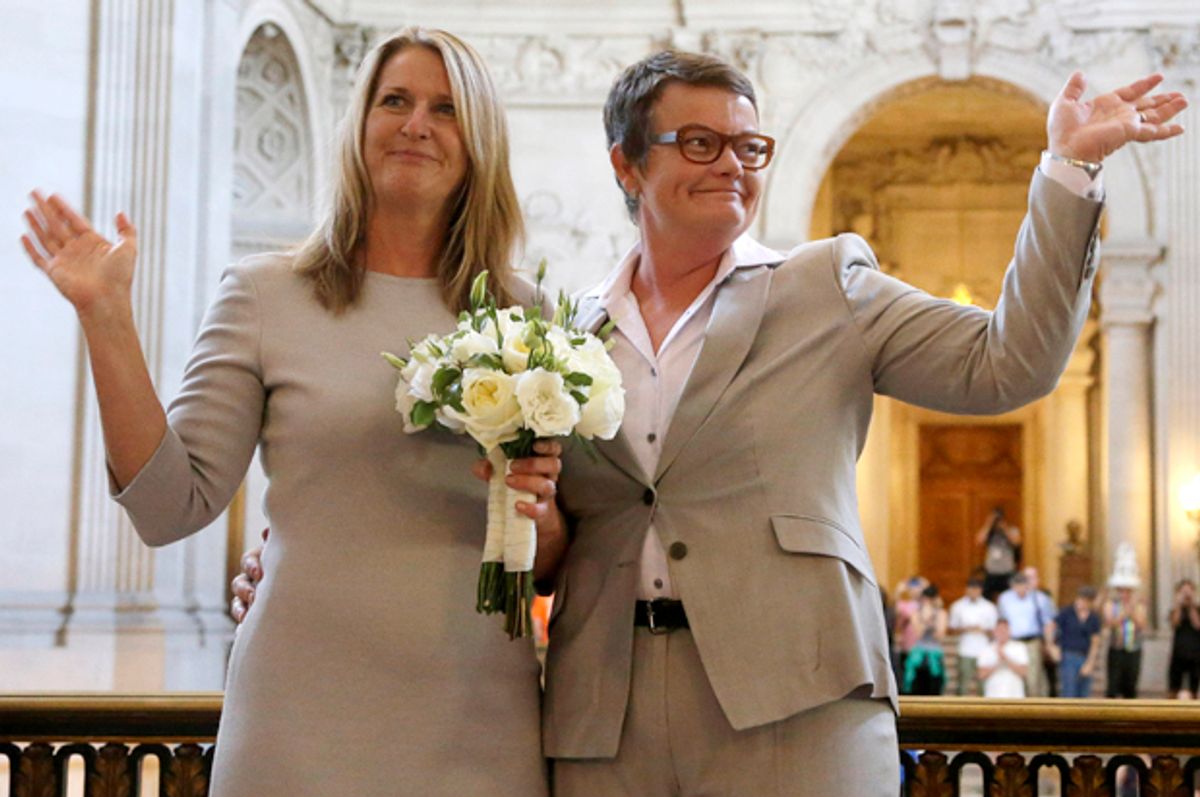

The tireless Griffin also found the four plaintiffs. Griffin knew Kristin Perry and Sandra Stier through his work on a ballot initiative to support early childhood education. Perry was then the executive director of a statewide commission created by that initiative. Perry had wed Stier in 2004 in a civil ceremony in San Francisco after Newsom’s announcement. After the court invalidated their marriage just months later, the couple could not bear to repeat the process in 2008, when the California Supreme Court gave them another opportunity to marry.

Griffin found Paul Katami and Jeffrey Zarrillo through the couple’s activism. In April 2009, an organization called the National Organization for Marriage (NOM), which opposes same-sex marriage, released a video titled The Gathering Storm. Set against lowering clouds and portentous music, the film depicted individuals fearful of what the advent of same-sex marriage would mean for them. “I am a California doctor who must choose between my faith and my job,” said one. Frank Rich, then a columnist at the New York Times, dubbed it an “Internet camp classic,” a cross between The Village of the Damned and A Chorus Line. In Stephen Colbert’s parody, lightning from “the homo storm” turns an Arkansas teacher gay, while a New Jersey pastor complains that gays had converted his church into an Abercrombie & Fitch. Katami and Zarrillo wanted to respond more seriously. Katami, a fitness expert, had made several films, and Zarrillo worked in the entertainment industry. Within two days of viewing The Gathering Storm, the couple produced a video called Weathering the Storm that provided point-for-point rebuttals to the claims made in the NOM video. When Griffin saw the response video, he sought the couple responsible for it.

These two couples were a lawyer’s dream. They represented different genders at different stages of life. At the time of trial in early 2010, Perry, who was forty-five, and Stier, who was forty-seven, had been together for eleven years and were raising four sons together. Katami, who was thirty-seven, and Zarrillo, who was thirty-six, had been together eight years. They tracked social sensibilities—then as now, it was more familiar to see two women raising children than to see two men doing so. Perry had also spent her entire career protecting children. There was only one serious wrinkle. Stier had previously been married to a man, a fact that could undercut one of the plaintiffs’ key arguments: that homosexuality was an immutable trait.

Faith in the judicial process underwrote the plaintiffs’ participation. When first asked whether she was interested in a project to restore marriage equality, Perry pled “gay-marriage fatigue.” Informed it was a federal lawsuit, she changed her mind: “We get to talk about this in a nonpolitical way? Now I’m really interested.” Katami had a similar reaction. He felt the lawsuit would “put a respectable face to the fight,” elaborating—“I didn’t want to just come out with my arms swinging.” It may seem odd to think of a judicial proceeding as a “nonpolitical” event, or an adversarial proceeding as not requiring a participant to come out with “arms swinging.” Yet both Perry and Katami correctly intuited that federal litigation would be more civilized than a political debate. And it would certainly offer more decorum than the physical violence Katami had experienced in the past—as he would testify during trial, Katami had been pelted with rocks and eggs during his first visit to a gay establishment.

Meanwhile, AFER searched for co-counsel to balance Olson’s reputation as a staunch conservative. The AFER team worried that if Olson brought the suit alone, he would be viewed as trying to throw the case in favor of the opponents of same-sex marriage. In a May conference call with AFER principals, Olson suggested David Boies. The reaction was explosive: “Everyone on the call said, ‘Oh my God, do you think he would do it? That would be fantastic.’ ” Olson would later write: “California’s motto, ‘Eureka’ (‘We have found it’), leapt to mind.”

David Boies was sixty-seven when approached to be co-counsel in Perry. If Olson has a canine quality, Boies’s profile is more avian—a domed balding head and an aquiline nose. The president of the Young Republicans club while in college in the 1960s, Boies soon realized he “was on the wrong side” of the battle for civil rights. He became a Democrat soon after graduating from Northwestern University, and went to work defending civil-rights workers arrested in Jacksonville, Mississippi.

Although he was, like Olson, a private lawyer in a large firm, Boies had significant credentials as a liberal litigator. In 1986, he won an injunction barring the Republican National Committee from suppressing the vote of racial minorities through unevenly enforced ballot security measures. In the early 1990s, Boies recovered $1.2 billion from companies that sold junk bonds to failed savings and loan associations. And of course, there was Bush v. Gore. Or, as Boies put it: “Every lawyer is used to losing cases. I lost the whole fucking country.” Several days after the conference call among AFER principals, Boies received a call from his former adversary. Boies says it took him fifteen seconds to accept Olson’s invitation. Olson says it took him less than one.

From a public-relations perspective, the match was inspired. The coming together of these lawyers symbolically reunited the two halves of the country. Far from downplaying their legendary clash, Olson and Boies used Bush v. Gore as a leitmotif throughout the public-relations strategy that accompanied the litigation. Boies would joke that he would be responsible for persuading the four justices who voted with him in that case, while Olson would be responsible for the other five. The pairing was less odd than it seemed. In the wake of Bush v. Gore, the two lawyers had become friends who vacationed together with their families. As Boies reflected, “You get so deeply involved in a case that about the only person that really appreciates what’s going on is the lawyer on the other side, who’s just as deep into the weeds as you are.” Sherlock Holmes might have said the same of Professor Moriarty.

The plaintiffs began to lay the foundation for their case. On May 20, Katami and Zarrillo met a Gibson Dunn associate at the Los Angeles County Clerk’s Office. The men submitted an application for a marriage license, which was, as expected, denied. The next day, Perry and Stier went through the same exercise at the Alameda County Clerk-Recorder’s Office. On May 22, a Gibson Dunn associate quietly filed the suit.

The California Supreme Court upheld Prop 8 against the procedural challenge, as expected, on May 26. But it did preserve the 18,000 same-sex marriages performed from June to November 2008. Ron’s sister Donna and her wife, Julie, were safe. The court reasoned that, unlike the 2004 Newsom weddings, these weddings were valid when performed. Nevertheless, this decision left California with an odd patchwork of marriage law. If Donna and Julie had divorced and then sought to remarry each other, they would not have been permitted to do so.

The next morning, the Perry plaintiffs and their lawyers held a press conference to announce their suit. They assembled at the Millennium Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles, before an audience bristling with national media, including CNN, Fox News, the New York Times, and NPR. Nary a rainbow flag flew. The conservatively attired lawyers and plaintiffs lined up before alternating California and American flags. Griffin introduced Olson and Boies. Both lawyers heralded the bipartisan nature of the suit, declaring that they sought to vindicate the right to marry for all Americans. “Creating a second class of citizens is discrimination, plain and simple,” Olson boomed. “The Constitution of Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Abraham Lincoln does not permit it.” When they opened the floor for questions, gay-rights activist Karen Ocamb immediately challenged Olson: “There’s tremendous suspicion in the LGBT community about your involvement in this because we never thought you were pro-gay.”

The major gay-rights organizations also gave Perry a frosty reception. On the day AFER announced its lawsuit, nine LGBT advocacy groups—including the ACLU, the Gay and Lesbian Advocates and Defenders (GLAD), the Human Rights Campaign (HRC), Lambda Legal, and the NCLR—released a joint statement responding to the California Supreme Court’s decision to uphold Prop 8. The statement exhorted individuals “to go back to the voters.” While acknowledging the allure of a federal lawsuit, the groups described it as “a temptation we should resist.” The statement made no mention of Perry. However, Griffin and his colleagues interpreted it as an assault.

It was a fair inference. The advocacy groups had trumpeted their disapproval of Perry to the media. The New York Times quoted Jennifer Pizer of Lambda Legal as saying, “We think it’s risky and premature,” and Matt Coles of the ACLU as remarking sarcastically, “Federal court? Wow. Never thought of that.” In an interview with The Advocate, Coles elaborated that Perry was “an attempt to short-circuit the process, to go all the way to the end.” To movement lawyers who had spent years painstakingly assembling the foundation for a federal case, Perry seemed like a risk and usurpation. Their harsh reaction can only be understood against the backdrop of the national movement for same-sex marriage.

Reprinted from "Speak Now: Marriage Equality on Trial" by Kenji Yoshino. Copyright © 2015 by Kenji Yoshino. Published by Crown, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.

Shares