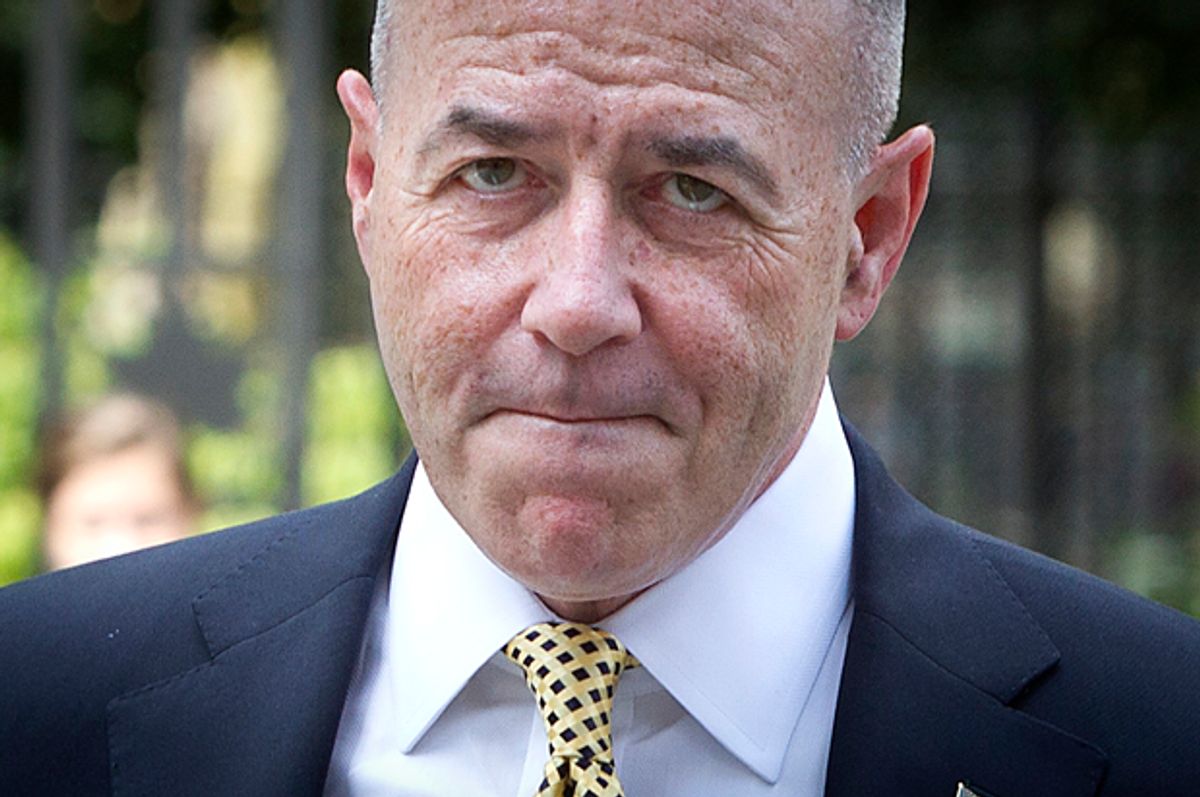

If someone told the average well-informed New Yorker in 1995 that Bernard Kerik would be spending his time 20 years later promoting a new book about criminal justice reform — and that book would be pro-reform, and not an attack on reformers — they'd probably think it about as likely as a Boston Red Sox fan becoming Gotham's mayor. Yet that indeed is what the man who was once Rudy Giuliani's longtime right-hand man, as well as President George W. Bush's nominee to lead the Department of Homeland Security, is up to these days. Amazing, what a decade-and-a-half spent out of power, eight felony charges and four years in prison can do.

Recently, Salon spoke over the phone with Kerik to discuss "From Jailer to Jailed: My Journey From Correction and Police Commissioner to Inmate #84888-054," his new book on his time behind bars and his newfound dedication to criminal justice reform. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

When did you start thinking about writing a book on criminal justice reform and your experiences? Was it something you considered doing before you went into the system yourself?

I started writing before I went away. Actually, I was going through the process [already] — not necessarily on the policy issue, just from a memoir perspective to follow up on my first book — but when I got in the system, I came to learn quickly that the system was very different than I thought it was. I started to see things that I just was unaware of, that I never paid attention to; and, I’m embarrassed to say, that I didn’t know. And at that point, it changed.

What was it that caused you take a step back and reconsider how you viewed the criminal justice system? Was it any particular incident or moment? Or was it just a result of the overall experience?

I started to see that ... we’re creating a permanent underclass in American society that nobody really pays attention to.

I think most importantly was to get to meet some of the people in prison that — you know, look, I’ve been in this business 30-35 years. I’ve put a lot of people in prison, bad guys who did bad things. And that’s what you think of when you think of a convicted felon, you think of [a bad guy] in prison.

But to get in there, and then meet a commercial fisherman that caught too many fish, who’s really a good and decent guy; who’s worked his whole life since he was like 17 in the fishing industry (now he’s like 55 or 60); and has two boys, and people that worked on the boat — his wife worked for the company. And his whole life is in disarray because he caught too many fish, or the wrong size fish, that or whatever the case maybe.

To see these young kids, young men out of Baltimore, Washington D.C. — these young black men, 19-years-old, first-time, non-violent, low-level drug offenses; 10-15 year sentences... Don’t get me wrong, I put people in prison for drugs — lots of drugs, tons of cocaine; millions and millions of drug proceeds — but to give somebody 10 years or 15 years, you institutionalize these young men. You suck all the societal values; whatever they had, they loose, and they go back into society as a thug, as a monster, because of what they’ve learned in prison.

Have you ever wondered to yourself why this was such a surprise to you, considering your lengthy and successful career? Have you wondered why you didn't seek out more information before it became your lived experience?

It’s not that you don’t seek it out. It’s, basically, you don’t have access to it, as a cop, as a law enforcement executive.

People compared my time at Rikers to the same as overseeing a prison, but Rikers Island is not a prison; Rikers Island is a massive jail system. My average length of stay was only 45 to 54 days. You’re not rehabilitating anyone in that time ... A prison is a very different environment, number one.

But number two, as a police executive, you’re focused on getting the bad guy. You’re focused on keeping streets safe. You’re focused on keeping society secure. But there was no time during that period when ... I would have access to ... [knowing we] locked up people criminally for regulatory violations — the commercial fisherman, the hunter that uses the wrong ammunition, or shoots the wrong animal, or has the wrong permit ... I didn’t realize that we actually turned people into convicted felons for that stuff.

So it’s not that I would have had access to it; it’s not that I would have known ... I promise you there’s nobody out there that’s in the positions that I was in that ... understands the system like I do. They couldn’t because they haven’t been in it. They wouldn’t see it.

Would you have behaved differently as a law enforcement office if you knew more about where you were sending people and the experience that likely awaited them?

I don’t think there’s much I could have done, other than push for legislative changes. I’ve heard Bill Bratton and I’ve heard other administrators talk about over-incarceration, and stuff like this. The only thing they can do — or the only thing I could have done at the time, if I was aware of some of this stuff, if that was my oversight and I knew about it — is pull for legislative reform, which is my principal focus now.

The reality is the everyday, average American citizen has absolutely no clue what the system consists of ... They just don’t. Unless they’ve been affected in some personal way, they’re not going to know. And the problem with that is, you’re not going to care about anything that you don’t know exists; you’re not going to do anything to fix something that you don’t know is broken.

So how are you going to grab their attention and help them see that there's a problem here?

I make it simplistic for the everyday American. I have one question [I say] you should ask your legislator: How is it possible that the United States is five percent of the world’s population, yet holds 25 percent of the world’s prisoners? How is it possible that we have more people in prison in this country than Russia and China? How is that possible?

I also think going into the 2016 election, it’s extremely important that the next president has criminal justice reform in the top five domestic issues on their plate ... Whatever party they’re from, whatever side of the aisle they’re from. This isn’t a Democratic issue, and it’s not a Republican issue; this is an American issue. This is something the next president has to address, one way or another.

Let's say it's January 21, 2017, and the next president has you in the Oval Office and is asking you to share with them a handful of reforms you think they should get to work on ASAP. What would you recommend?

Most importantly, the mandatory minimums in sentencing guidelines have to be reevaluated or repealed ... You have some of the most brilliant legal minds in this country, including Supreme Court justices, who are basically saying that the mandatory minimums in sentencing guidelines are completely draconian and have to be either abolished or revamped.

Number two, we have to stop taking regulatory, administrative, and ethical issues and turning them into criminal conduct. People can be held accountable from a regulatory agency. They can be fined. Their licenses can be suspended. You can seize their stuff. That commercial fisherman that catches too many fish? Take his fish. Do something. But don’t charge the guy with criminal conduct so that the guy is completely rendered useless as an American citizen for the rest of his national life. That’s wrong.

What about changes within the prisons themselves?

Real programs. Real [rehabilitation] programs. Where I was ... they had A.C.E. classes: Adult Continuing Education classes. These are real examples [of the subjects]: quilting, chess, checkers. I can promise you, quilting, chess, and checkers are going to do nothing to reduce recidivism. They are going to do nothing to help a guy get a job on the outside. They are going to do nothing to teach him work ethics.

Some of the other classes they had — they had a real-estate class. The real-estate class was taught by a man convicted of real-estate fraud. C’mon! If that’s not bad enough, let me ask you: a guy attends a real-estate class, what’s he going to do with it? He’s a convicted felon; he can’t get licensed as a real-estate broker; he can’t do anything that’s regulated by the United States government ... Those inmates taking those real-estate classes and tax classes and business classes, they can’t get licensed. I don’t give a damn how good they are, they’re not getting a license. So, what are we really doing?

To recap, that's: reform mandatory minimum laws, reduce the number of violations that could result in criminal charges, and revamp rehabilitation programs within the prison system itself.

If I could throw in one more thing: solitary confinement. Solitary confinement has to be looked at on a national level.

Why do you say that?

We’re overusing and abusing solitary confinement. I think that it’s a necessary tool when you have somebody that’s a violent person, that’s a threat to an institution or a threat to staff or maybe threat to national security, or even a major escapist. But to take young men and women and throw them into solitary confinement from minor institutional violations ... you’re destroying people by doing this. I think people often forget that those people are all going back into society. We’re monsterizing young men and women bad enough already; you don’t want to stick them in solitary confinement for six months to a year and make them complete lunatics... Is that what we want?

Are there any broader, societal changes that we should consider? Sometimes the line between needing changes to our laws and policies and needing changes to cultural norms in general can get blurry.

The last and probably most important issue is, at what point is your debt to society paid? Because as it stands right now, your debt to society is never paid; you are punished until the day you die if you have a felony conviction of any kind ...

It could be for selling a whale’s tooth on eBay. A guy selling a whale’s tooth on eBay can wind up in federal prison as a convicted felon, and the collateral consequences ... with regard to his civil and constitutional rights are no different than if he were charged with mass-manslaughter. He's held in the same category. At what time, at what point ... is that American citizen re-made whole? Because at it stands right now, it never happens ever.

You're still a vocal and forceful defender of law enforcement officers, but you're also now working in parallel or in concert with many reformers who often find themselves at-odds with law enforcement. Does that create any strains in your relationships with former and current members of the criminal justice system?

It goes two ways. For the cops and the law enforcement people when they first hear what I have to say, or they hear the general topic, as soon as you say "prison reform" or "criminal justice reform" — somebody walks away thinking, Ah, this guy wants to let everybody out of prison. I think I may have gotten some of that initially, but after I talked to these guys, no matter who they are — even the legislators on the Republican, conservative side — by the time I get done talking with them, I make them understand where we’re failing. That’s the important issue here.

There’s people out there that believe take these kids off the streets for these drug violations, stick them in prison for as long as possible, and that makes society safe. Well, I can give you 20 reasons that’s wrong; and then when you think about it, you don’t have no choice but to agree with me ... I’m not different today of a law-and-order guy that I was 15 years ago. I believe in law and order ... But I just think we’re locking up too many people.

Shares