“It has always seemed to me that I have lived at a certain distance from life,” author-neurologist Oliver Sacks writes in the final pages of what will possibly be his last book, a memoir, “On the Move.” The reader can be forgiven for doing a double take at that, because anyone who’s read the preceding 400 pages has just absorbed an account of a gloriously engaged life, full of adventures, experiences, travels, discoveries, friendships, enthusiasms and above all, curiosity. “On the Move” is an enchanting window on just how much vitality you can pack into four-score years on this planet, and it puts most of the rest of us to shame.

What Sacks is referring to, however, is his love life. He was celibate from his 40th birthday (marked by a robust, if entirely transitory fling) until his late 70s, when — plagued by a melanoma in his right eye that left him partially blind, knee surgery and sciatica so bad it made him contemplate suicide — he fell, greatly to his surprise, in love. Sacks has been with his partner, the writer Bill Hayes, for the past eight years. In February, via an op-ed in the New York Times, he announced that the melanoma has spread to his liver and that he has only months to live.

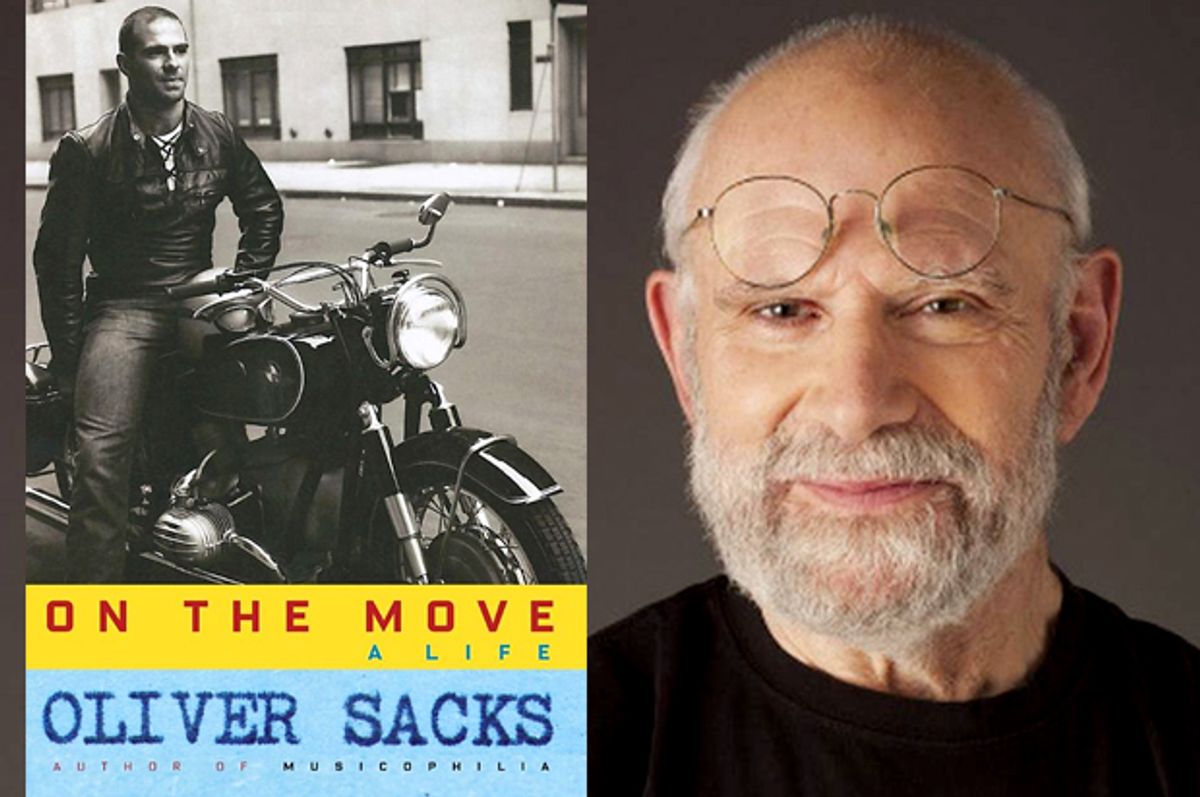

We will lose a lot when we lose him. “On the Move” illustrates what an exceptional human being he is, from a childhood illuminated by his passions for chemistry and music (related in greater detail in his earlier memoir, “Uncle Tungsten”) to a youth spent roaming his native U.K. and the U.S. by motorcycle to an adult work life devoted to explaining the mysteries of the human brain and to helping those who live with any of its myriad irregularities to be better understood. He took LSD and befriended the poets Thom Gunn and W.H. Auden, as well as less-celebrated characters, such as the homeless friend he celebrates as “an utterly independent human being, a sort of modern, urban Thoreau.” He loves ferns and cephalopods and swimming and mountains and his patients. He is fascinated by seemingly everything, and, damn, the man can write.

But Sacks has also been the great chronicler of a fundamental change in the way we view the brain and its workings, a change that has unfolded over the course of his career. He might have been purpose-built for the task. That’s one reason why the penultimate chapter of “On the Move” is taken up with explaining the pioneering work of the Nobelist Gerald Edelman, whose theory of “neural Darwinism” Sacks considers “the first truly global theory of mind and consciousness, the first biological theory of individuality and autonomy.”

Edelman, who pretty much embodies the stereotype of the brilliant but inaccessible scientist, once turned to Sacks at a conference and said “You’re no theoretician.” Sacks also wasn’t much of a researcher, as he confesses himself, describing his bumbling exploits in various laboratories at the onset of his career. He always seems to be losing stuff, from precious tissue samples to his own manuscripts — although for anyone who writes as much as Sacks does (he claims to have filled nearly 1,000 journals), maybe the misplaced texts seem more expendable.

Sacks’ reply to Edelman was, “I know, but I am a field worker, and you need the sort of field work I do for the sort of theory-making you do.” True, but the idea that Sacks was primarily a collector of data really doesn’t do him justice. On the very last page of “On the Move,” he writes, “I am a storyteller, for better or for worse,” and as simple as that statement is, it hits the mark. He is a storyteller who was born into a moment when neuroscience needed just that, a time when biologists have come to realize that every individual organism — from a flatworm to such splendid specimens of humanity as Oliver Sacks himself — is the culmination of a story.

According to “On the Move,” the young Sacks’ superiors occasionally expressed frustration with his long, detailed, idiosyncratic accounts of individual patients and their problems, a propensity that naturally resulted in small, rather than “big” data. Nevertheless, Sacks’ early years at a headache clinic (resulting in his 1970 book “Migraine”) and his work with administering the drug L-dopa to the aging survivors of an epidemic of encephalitis lethargica (the subject of “Awakenings”) confirmed that “one cannot abstract an ailment or its treatment from the whole pattern, the context, the economy of someone’s life.”

In time, neuroscience would come to agree with him. New technologies that enabled researchers to examine the brain more closely helped undermine longstanding models in which “the nervous system was largely conceived as fixed and invariant, with ‘pre-dedicated’ areas for every function.” This was the thinking even as Sacks wrote the 1985 book that would make him famous, “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.” Yet the very format of that bestseller — a collection of case histories — subtly undermined that model.

“The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat” revived the case study as a literary form. This was partly due to Sacks’ prodigious literary gifts and inquisitive, imaginative mind, but what really captivated readers was the book’s grounding in physiology. Previously, the detailed case history was almost entirely the province of psychoanalysis and other forms of psychotherapy, treatments with not much basis in observable, testable scientific fact. Sacks, by contrast, explained how injuries and other changes to the brain could cause profound and often peculiar changes to the way people experience themselves and the world. He gave a popular readership a new view on the link between body and mind. Not long after, the rise of antidepressants and other mood-altering medications served to reinforce a new understanding of how our emotions are the product of our biochemistry as well as of our relationships and memories.

Meanwhile, neuroscientists were discovering that the brain, far from being as rigidly divided as a bento box, is in fact remarkably plastic. Sacks, plunging with characteristic zest into a study of deaf culture, would write of how “in the brains of congenitally deaf signers, what would normally be auditory cortex in a hearing person was ‘reallocated’ for visual tasks, and especially for the processing of visual language.” This suggested that the cortex — the part of the brain concerned with higher functions — “might be more plastic, much less programmed, than formerly thought.” Sacks found this “momentous, something which demanded a radically new vision of the brain.”

That vision was a storyteller’s vision. Edelman’s theories play such a large role in the latter part of “On the Move” because they transform “a world of shallow, irrelevant computer analogies into one full of rich biological meaning.” Edelman argued that very little of a human being is predetermined by genetic programming, that the brain is exquisitely adaptive and is constantly shaping and reshaping itself in response to its environment and what its owner needs to do to survive there.

No wonder Sacks recalls walking home after dinner with Edelman “in a sort of rapture”! (A bit later, he charmingly recalls a cow spotted during a drive upstate and thinking “what a wonderful animal!” as he imagined how that individual creature was constantly responding to its unique experiences.) This is why, he goes on to explain, “an infant does not follow a set pattern of learning to walk or how to reach for something” and why “there is no prescribed path of recovery; every patient must discover or create his own motor and perceptual patterns, his own solutions to the challenges that face him … we are destined, whether we wish it or not, to a life of particularity and self-development, to make our own individual paths through life.” It’s a beautiful vision, one that embraces an infinite spectrum of wonder, and a fitting farewell from one of the most welcoming and beautiful of minds.

Shares