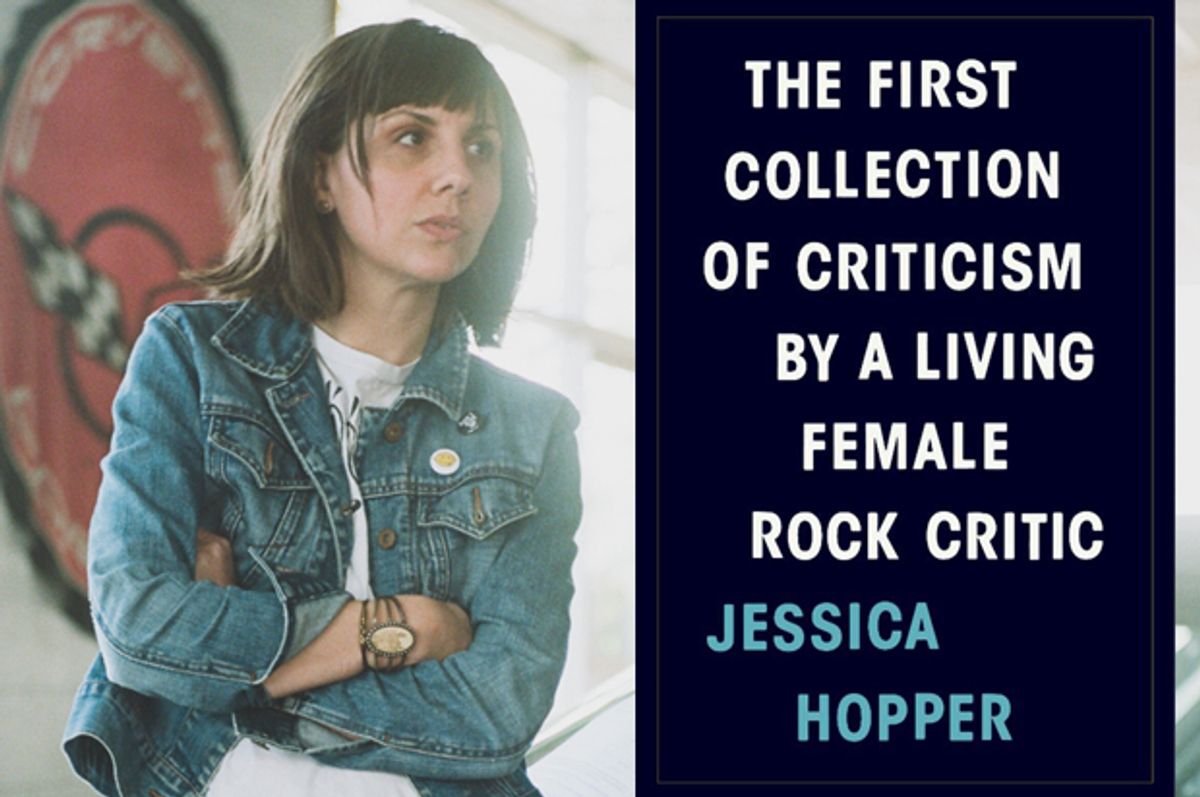

The dedication of Jessica Hopper's new book, "The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic," nods to some of the pioneers of music and cultural criticism: Ellen Willis, Lillian Roxon, Caroline Coon and the anthology "Rock She Wrote." However, the Chicago-based writer, editor and critic—who is currently the editor-in-chief of the Pitchfork Review—then goes on to nail exactly why her collection is needed, if not long overdue: "We should be able to list a few dozen more—but those books don’t exist. Yet. The title of this book is about planting a flag; it is for those whose dreams (and manuscripts) languished due to lack of formal precedence, support and permission. This title is not meant to erase our history but rather to help mark the path."

Hopper says the idea for a collection like this has been kicking around for over a decade, since Akashic publisher Johnny Temple originally suggested she publish a book of her columns. She kept the idea in the back of her head as she embarked on a freelance writing career—and when her longtime friend Tim Kinsella (also a musician who's played in bands such as Joan of Arc and Cap'n Jazz) inherited Featherproof Books in 2014, the timing was finally right. "Tim came to me and said, 'I want my first book at Featherproof to be a book of your criticism,'" Hopper recalls to Salon. "And I was like, 'Yess! Absolutely.'"

Although she "thought it would be easier than it was" to put the book together, ultimately things came together rather quickly. "The book itself was a process of a few months," she says. "It was basically a very intense summer and a few months on top of that to whittle away at what really belonged here." The pieces in "The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic" are diverse and important in their own individual ways—everything from a fascinating look at the synchronicity between indie musicians and advertising, and the (sadly still all-too-relevant) 2003 piece "Emo: Where the Girls Aren't" to a profile on songwriter David Bazan that explores his complicated relationship with religion and fans, and to a Village Voice discussion with Jim DeRogatis that reexamined (and gave renewed visibility to) the sexual assault allegations against R. Kelly. The book covers reported pieces, reviews and words originally published on her blog and 'zines, as well as mainstream publications, and is arranged into sections that are often unexpected—for example, one is centered on faith.

As Hopper looked back at her own work, she too was surprised by some of the threads running through the book. "There are certainly themes I wasn't anticipating, where I could see where ideas started, in pieces from 1999 that I didn't figure out until three years ago," she says with a laugh. "Things that unfolded really slowly. That was kind of rad and exciting just to see there's things I never stopped drilling down on until I really got to the meat of, like, 'Why does this bother me? Why do I have this totally weird fascination with Taylor Swift?'"

In a wide-ranging Q&A, Hopper checked in about how "The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic" came together and why the existence of a book like this is so important.

Once you had the book solidified and had a direction of where you wanted to go, how did you decide what you wanted to include?

We went through a few different organizing rubrics. I really lucked out that I had the help of an MFA student, this guy James, and a few other people who work with Featherproof, who are not necessarily music people—they're book people, they're writing people, looking at it not exclusively through the lens of, "What are the bands Tim and I want to read about?" The ultimate rubric for the book is, "Is this a good piece? Is this the best version of this piece? How does this fit into the arc of my weird, discursive career? What part does this piece play in the story of my work? Are there a million think pieces along this line? Is this that crucial?"

[Pieces] had to jump through a lot of hoops to get into the book by the end. I could tell with every successive thing where we would cut down another 10 percent of the book, another 20 percent of what we had culled together, [that] the message and the idea really came into focus. It was as if the book dictated itself, [it] gave us the direction once you put these things together. You're like, "Aha! This is the thread here" and "These six things go together."

Once we had everything that we knew was going in there, there were a few things where [we had to determine], what do these piece have in common? How do we connect "Emo: Where the Girls Aren't" and R. Kelly? They both happened in Chicago. [Laughs.] I didn't necessarily expect there would be a faith chapter or section; I just knew the David Bazan piece was one of the most important things I've written.

I was especially happy to see articles from your 'zine and blog interspersed with writing that appeared in online or print publications. It really sends the message that criticism is valid no matter what the medium, which I think is an important point to convey.

I think that's one of the ways that made the book more dynamic, too. I think you can see the ways I've evolved as a writer. I didn't want every piece in there to be perfect. You see so much more too of what it's like when I'm writing for this audience, or how I get edited at this publication. [Laughs.] Just what my writing's like when it's more like my heart guiding it, or what my work is like when I have a year and a half to report on something, as opposed to something that I'm spleening out after going to a Pearl Jam show.

I [also] wanted those to be there to show people who are young, hopeful writers too that for years, I mostly just wrote for myself. That doesn't make me any more of an amateur—it's a very valid way to develop and build your voice. I think those pieces sometimes work as commentary on other things I'm doing. Some of those things where I'm specifically talking about my reporting, or listening to a bunch of records because nobody wants to hire me to write about my year-end, it's a little bit more process-y.

It's a lot freer too. You're not constrained by word counts or biases you might have to keep in mind when you're doing something for a more official publication.

I'm really all about reclaiming the fangirl, you know? And to show people that very much still exists, even if I'm doing more straight-ahead criticism, that there's still that person who's eager and outraged and spazzing.

It is interesting how much writing you read, and you wonder if they even like music. Which I've never understood.

A lot of people come out of the more formal training of journalism school. You're supposed to be a generalist, and there's also this idea that for some reason we're supposed to be objective. It's like, we're critics. What are we going to do, write a piece that's like, "Well, objectively, this is decent music, except I hate it." [Laughs.] There are people who make a living writing like that. All the critics I always loved, and the writers I still love, are people who, even if I don't agree with their opinions, they are steadfast and articulate about them.

And you have to respect people like that.

Because there's a risk. I'm not interested in music that doesn't take a risk. Some people have more space and permission to take risks in the world and not be punished for it, and take up that space and be outspoken. Other people have a very real professional penalty or similar. If you're a woman of color writing on the Internet, it's totally different than if you're, like, an older white dude writing at a newspaper. There are different consequences for what you write.

I came out of the fanzine world; I grew up reading people being very passionate and real love-it-or-hate-it about records or bands. This very '90s, p.c.-ness, and the p.c. backlash within punk. I came up in a time where there was this constant warring about the values of the music and what were we supposed to respect and what were we supposed to fight against. I've always taken it so seriously. I feel like I have no other option than to be like, screaming from the top of the building yes or no, decrying what I love or hate.

For women working in music journalism, it's a no-brainer that this book is important and long overdue. For any skeptics out there, explain why this book is important.

Sometimes you have to wave a flag around any sort of precedent in order to make a path. Despite the fact I'm pretty successful at what I do, people are saying, "No, it's egotistical," basically, to put out a collection of your writing. Or people saying, "You're not a canonical writer" or "You're too young." You know what? Let's open up the canon. Because if I don't fit in it, then who the fuck does? Not to sound too Jesus-y about it--I'm not a martyr--but I wanted to put this book out to create the precedent. Not so much because I want any sort of accolades or attention or whatever, it's because I want books from Hazel Cills and Doreen St. Felix, and every single person that works at Rookie. All of these things.

I don't want them to have the arguments that I had to have to prove ... I don't want them to have to fight to sort of have this book for themselves. To have their book for themselves. And for the rest of us—I want to read their books. We shouldn't have to have our precedents, just to take up space at the table, have to be gendered. But they are. And to that, I say, my book's not even out yet and it's in its third printing. So everybody can fuck right off. [Laughs.] Long story short—fuck the haters.

Shares