“Mad Men,” which concluded its award-winning eight-year run on Sunday, invited viewers to look anew at the 1960s.

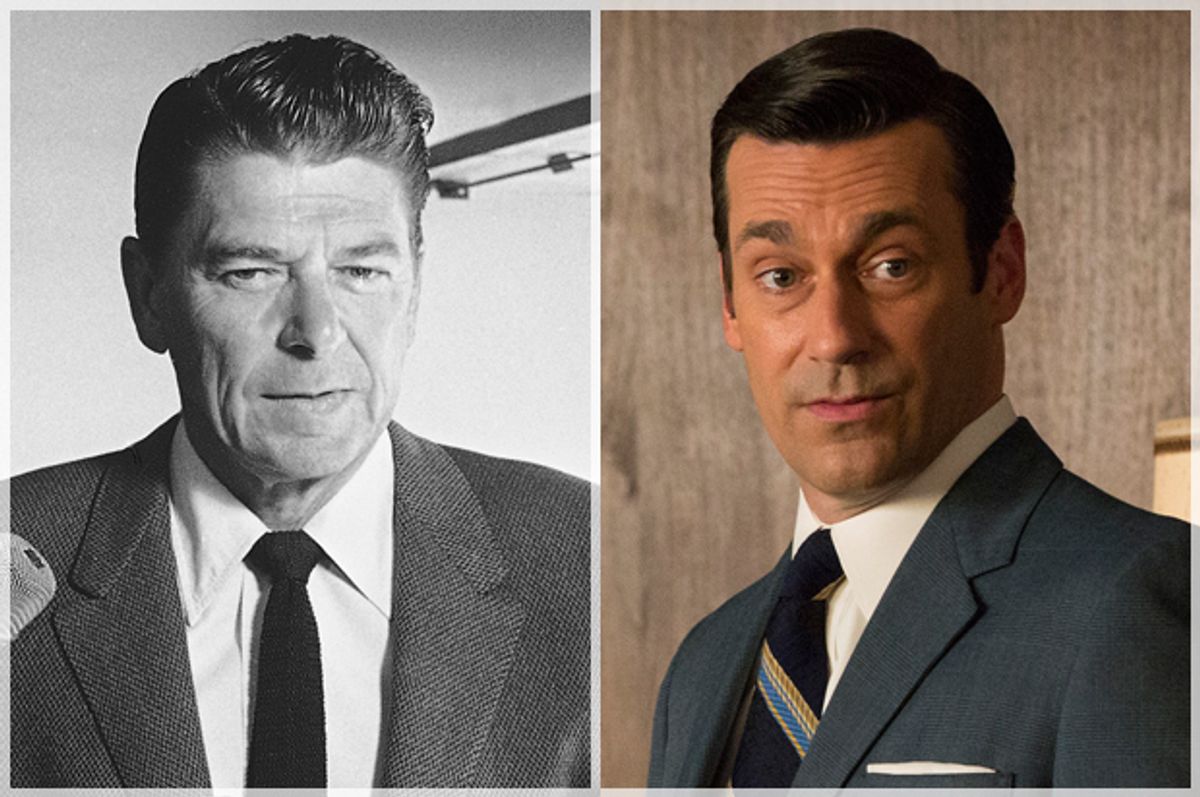

Rather than focus on the hippie left or the civil rights movement, as documentaries and feature films have done in the past, “Mad Men” focused on the corporate elite, sparking an appreciation for midcentury style if not exactly for midcentury substance. In “Mad Men,” the 1960s come off as transformative, a decade in which the radical left looks a bit foolish (those silly Greenwich Village ne’er do wells!), country club Republicans look increasing out of step, and the confidence of one era is fading into the uncertainty of another.

The one theme that has overwhelmingly dominated the show has been the question of freedom. For eight years, Don Draper has explored how much freedom a person can have and still feel valuable, able to find fulfillment without encountering limitations. As a man forever finding new freedoms — from his childhood, his background, his wives — Don Draper still knows the intractability of being grounded. In the series’ most memorable moment, Don wins the Kodak account by using a freedom-creating technology — a rotary slide projector — to tell the story of a life, of a courtship, a marriage, parenthood. So moving is his tale that a colleague leaves the room in tears. The account is won.

Whether the show’s creator, Matthew Weiner, knew it or not, the same question that dominated “Mad Men” has also come to the forefront of professional historians’ debates about the 1960s. Seeing the decade as a time when Americans were demanding not only liberation from age-old authorities but also free markets in a Free World, historians have left behind old interpretations of the decade, finding focus in the same question that Weiner settled on, a focus that may, finally, give us a way to move beyond arguing about the decade we can’t seem to leave behind.

The first professional historians of the era were mostly former leftwing activists themselves. Unsurprisingly, they saw the decade as a dramatic turning to the left. Authority was under attack. People were in the streets. Clothing styles loosened. Women didn’t have to worry about the number of inches between their knee and their hemline. Men didn’t have to worry about growing their hair below their ear. Ties became unfashionable; tie-dye was in.

Sure, radicals wanted more. Some wanted an overhaul of capitalism. Some wanted the government to provide not only material wellbeing, but spiritual wellbeing, too. Thus their frustration when the Vietnam War didn’t end as quickly as they wished, when civil rights legislation didn’t address persistent economic disparities, when women weren’t quite elevated to the status of equal.

For a long time, that’s how the 1960s were remembered: as a time when American culture moved to the left and authority came under attack, but the more formal institutions of power didn’t change as much as radicals wanted.

About two decades ago, historians began to readjust their focus. In the midst of the Reagan Revolution, scholars began to examine the origins of the New Right, and, lo and behold, they found its origins in the 1960s as well. Instead of the leftwing SDS, scholars began to focus on the Young Americans for Freedom (YAF), which started the year after SDS but always had a much larger membership. Rather than dismiss Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential run as a brief moment when Republicans went a little crazy before falling back on its patrician heritage, historians began to understand Goldwater as an early voice forging the way for the libertarianism that reverberates today in the Tea Party. For about two decades now, historians began to interpret the 1960s as, most prominently, the gestation years of the New Right.

But still, we had now way to understanding the 1960s as a whole. Was it a time when authority was questioned and culture moved left? Or was it the seeding years of Reagan’s America?

Well, it turns out both answers are right, a truth that makes sense only when we adjust our frame of reference, using as the chief interpretive focus the question of freedom.

As I was writing my new book on the friendship between the radical leftist Norman Mailer and the rightwing firebrand William F. Buckley, Jr., it became clear that almost every subject the left and the right debated in the 1960s centered on the question of freedom. Using the two men as stand-ins for the left and the right in the early 1960s, both Mailer and Buckley made their arguments on behalf of increasing freedom for Americans. Buckley thought the United States should exert unlimited energy in fighting the Cold War, because to lose the battle against the Soviets would be to jeopardize American freedoms. He even endorsed preemptive nuclear strikes to make the point. Mailer, on the other hand, demanded a cold turkey end to the Cold War. All America was doing, he argued, was wasting its wealth on faraway countries that were only hating us more. How were the people of Vietnam freer because of us? He thought instead we should spend our capital at home, funding projects that would enhance Americans’ quest for a more fulfilling life.

When it came to the student revolts of the middle 1960s, Buckley thought the youthful wildlings were making foolish arguments in the name of freedom that were only going to jeopardize America’s standing in the world. Why were serious people taking these children seriously? Mailer, meanwhile, thought the students were making a powerful case about the limitations of a conformist culture, which was, of course, the opposite of freedom.

But as the 1960s turned increasingly violent, something startling happened to both men: they began to confront the limits of freedom. How much freedom was too much? Could a society survive when everyone “did your own thing”? Both Buckley and Mailer recoiled at the new demands, and understood the violence of the later 1960s as the birthing of a new order, one in which freedom was the winner.

Thus by the 1970s it wasn’t the left or the right who had triumphed, but freedom. There were some new civil rights laws, and we still question authority while wearing shirtsleeves or short skirts, not afraid to call an adult by his or her first name or even to use curse words. At the same time, free markets are still today a clarion call and deregulation has become second nature. Labor unions continue to struggle against rhetoric that people should have the freedom to join a union or not.

Freedom triumphed.

It would be foolish, however, to think that this happened without costs. And, looking back from the perspective of fifty years, it’s apparent that the cost extracted was the sensibility that we all have a responsibility to work toward the common good, that we are part of a collective whole.

This isn’t to say the people demanding freedom in the 1960s didn’t have good reasons for doing so. It’s unfathomable to say a black person who couldn’t vote in Selma, Alabama was unjustified in feeling that America had wronged him or her. It’s useless to demand the nation go back to a simpler era, because that era was, of course, greatly flawed.

Instead, we should today attempt to imagine a new set of assumptions whereby we focus on the questions now about whether the right or the left won the 1960s, but how a society can honor the demands of those whose voices began to be heard in the 1960s, while recognizing that, while doing so, we owe a certain sense of our spiritual wellbeing in realized we are part of a larger community.

Without finding that balance, we risk turning out like Don Draper, forever searching, embodying that haunting image that began each episode, of a tragic figure falling to his death, all alone.

Shares