There may be nothing we humans are more at ease with, or more practiced at, than talking about the weather.

Not, of course, that we're particularly apt to understand exactly what it is we're discussing. As author and journalist Cynthia Barnett establishes early on in "Rain: A Natural and Cultural History," for all our dependence on rain, we misunderstand it "at the most basic level -- what it looks like."

"We imagine," she writes, "that a raindrop falls in the same shape as a drop of water hanging from the faucet, with a pointed top and a fat, rounded bottom." Yet "that picture is upside down. In fact, raindrops fall from the clouds in the shape of tiny parachutes, their tops rounded because of air pressure from below."

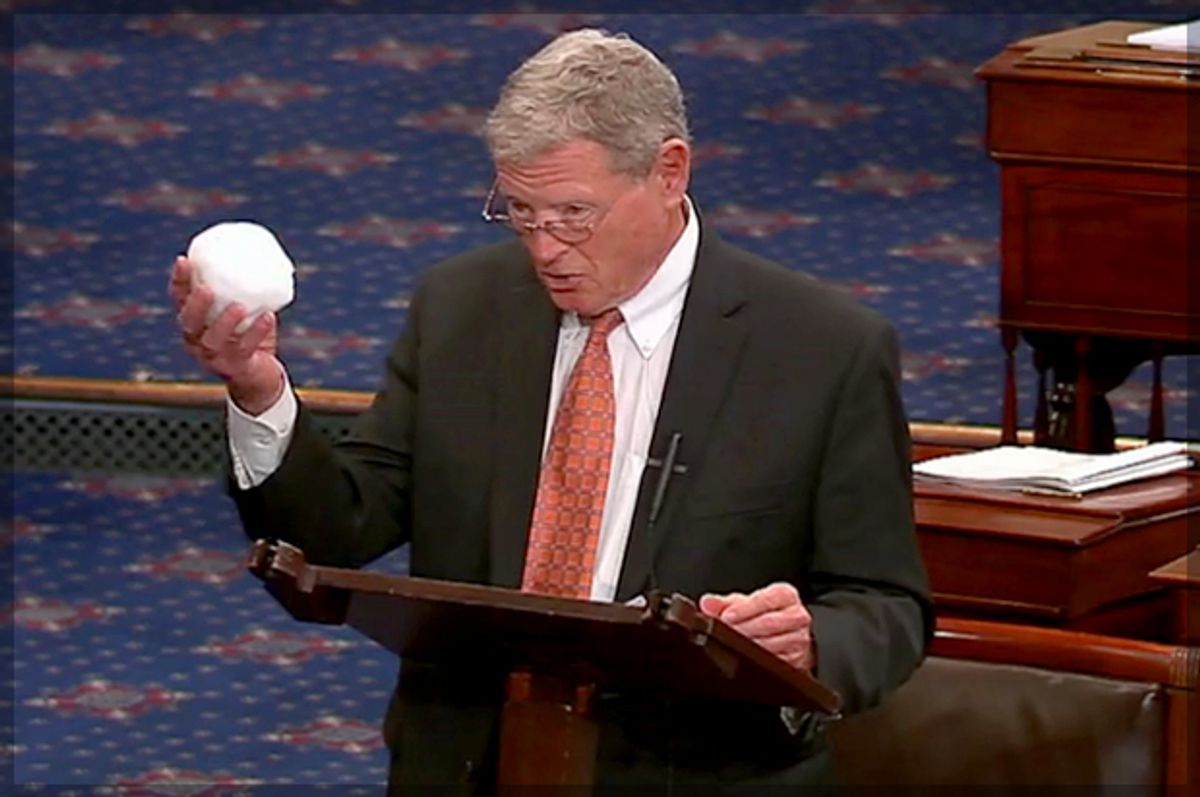

It's all more or less downhill from there. Rain, as Barnett lovingly portrays it, is one of our most profound shared human experiences, a source not just of life, but of art and religion, and a reminder, in modern times, of our connection to nature. But it's not, as she demonstrates over and over again, something we always approach with strict rationality. In our earliest days, we sacrificed children to the rain gods. In the 1890s, the U.S. Congress funded a scheme to literally blast rain out of the sky using cannonballs. Today, Republican leaders deny the clear connection between what we're doing to our climate and the droughts and deluges we're now facing.

Salon spoke with Barnett about the lessons -- and inspiration -- we can take from humanity's long, complicated history with rain. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about how this book came to be.

So water has been my beat for many years. I’ve worked as an environmental journalist and I’ve written two other books. They were more prescriptive, more wonky. I felt like they were so important and that everyone would want to read about water, which seems to be one of the pressing sustainability issues of our time. But I found with those books that I was always writing for the environmental choir, and I really wanted to write a book that would appeal to a larger audience.

I came to see weather and especially rain as a way to talk to the general public about water and about climate in a way I hadn’t been able to before. So the whole idea behind this is to bring new readers to the water story that I’ve covered for so long and to try to use poetry, and Mackintosh raincoats and the heady smell of rain to talk about those bigger issues.

You kind of preempted my first question: It seemed to me rain was like really an artistic muse for you, more than anything else.

You know, it is. I’m not sure if I knew that setting out. But I think it’s true that I’ve always loved rain, since my childhood; I grew up in Florida and rain, it’s got such drama to it. It always makes a day dramatic and fun in a way that a sunny day is not. I think rain is definitely a muse. But it’s also a way, I think, to draw a broader audience to water and to climate change. And the way I specifically got on this is that I would go around the country, talking to audiences about my previous book, "Blue Revolution," and I found that even people who didn’t want to talk about climate change or deny climate change, they still loved to talk about the weather, right? They loved to talk about extreme storms, the epic drought, and they loved to talk about hurricanes, and harder precipitation and all of these other things that we’re seeing.

I began to see rain, too, as a way to draw other people to the story. I think it’s a way to maybe help turn the shouting match over climate change into a conversation. Because everyone loves to talk about rain, and that’s one of the great things about rain, it kind of brings us together. And even when you’re in a downpour with a stranger, on a train or outside somewhere, you just start talking to that person about the weather. It’s a beautiful thing about rain.

What was really interesting to me was this long history we have of superstitious and mystical attitudes about rain, and the way we still hold some of those today. There’s a recurring theme of Congress, and people in general, ignoring scientists when it comes to these matters, and I was wondering, do you think mysticism still plays into that?

I’m really glad you picked up on that. Part of what I wanted to do ... I’m really interested in environmental history. Even though I’m a journalist, I went back to school and got a master’s degree in environmental history. I love how stories from the past can help us see how to get through challenges now. I think that period you refer to, for example, the 1890s when Congress bankrolled this really bizarre scheme to shoot rain out of the skies with cannons -- at that time meteorologists were saying this isn’t going to work, loud noises don't actually cause rain. Yet there was this belief that they did, especially after the Civil War because so many of the battles were really rainy and muddy, so people were increasingly convinced that wartime battles and guns and cannonades and cannon-fire would bring down rain. But the meteorologists at the time were saying no, the Civil War was fought in the rainiest part of the country and that’s why it’s a rainy war.

I tried to make the point that then as now Congress listened to the influential uninformed over its own scientists. Modern times resemble those rainmaking 1890s more than the emissions-lowering 1990s, I'm afraid.

I think that’s absolutely a theme, and when you point out the mysticism, that goes back to the earliest human communities. One of the very first gods worshiped was a god of rain and storms, and we all always had some mystical way of trying to stop rain or bring rain and that continues today. In Texas, we had Gov. Perry praying for storms. In Georgia, the governor has prayed for rain. It’s this really deep, intense part of our humanity to really wish and hope that in the end we’ll be able to control the atmosphere. And of course, the lesson is that we can’t. But we keep trying. We keep praying for rain and we keep trying to bring it on or stop it.

An ironic lesson, as you point out, at this point where we finally have changed the climate and the weather, but we still do not have control over it.

Exactly. That was the incredible irony of this book and this research, is that we tried so hard for all of human history, in one way to another from storm gods to cannons to Jupiter Pluvius, we always tried to change the rain -- or believed we could control it -- and then in the long run it turns out that we did change the climate, only not in a way we ever could have imagined. Not in a way we ever would have wanted to.

So you write in the book how modern living, with our reservoirs and irrigation and water pipes, dulls us to our dependence on rain. Do you think with climate change, specifically with California’s drought being such a huge story in the news right now, that we’re perhaps remembering again that we have this really long history of depending on rainfall?

I think that’s a really good point. I would say yes, that throughout the 20th century, water problems were sort of hidden for us because our pipes are underground, water flows out of the tap like magic, we don’t really have to worry about clean water like other parts of the world do. But I think two things are changing that. One is the epic drought that you mentioned, and seeing those images from the arid West from our trusty reservoirs dropping as low as they are. But then also in the East, you might remember last year when harmful algae in Lake Erie resulted in a drinking water ban for the city of Toledo -- those sorts of things are happening more in the Eastern half of the country because of climate change. As waters become warmer, the scientists say we might see more of these harmful algae outbreaks.

So I think when it comes to both drought and the water quality impacts of climate change, people really are become more aware of water issues than they have been at any time since the early '70s. People were really aware at that time because we were damming the West and there was visual pollution in rivers and the industrial cities of the East, in some cases rivers caught fire, like the Cuyahoga. So there was this great public perception of what was happening to water and people became very engaged in water. That’s when we passed the Clean Water Act and created the EPA and other environmental safeguards. Really, I think now is the first time since then that people are really interested in water again. They are saying, wait a minute, we thought this was so easy to turn on our tap and get clean water, or we thought this was a long-term sustainable supply -- and things are not as we thought.

This goes back to the point I made earlier. I really think that water and weather -- but maybe specifically water -- will be the way we come to talk about climate change in the country, because all of the initial impacts of climate change are being seen in water-related impacts: drought in the West, sea-level rise where I live in Florida, great water quality concerns in places like the Great Lakes. These are all aggravated by climate change. Maybe the conversation we can have is surrounding water and weather and rain -- to take it out of the political realm and talk about it in some of these other frameworks is probably helpful.

Would you remove the phrase "climate change" from the conversation altogether?

I think it’s really a small and vocal group that doesn’t want to talk about climate change or denies climate change. I see this broad group in Middle America that we’re sort of not writing for. I think of this group as "the caring middle" -- I teach environmental journalism at the University of Florida, and this is something I talk to my students about. If you think of people in your own family, like an aunt or grandparents, there’s this large group in Middle America who would care about climate change if they really understood it. I think a big part of the issue is that we’ve done a poor job of communicating climate change.

So part of what I wanted to do is to help the caring middle understand climate change. That’s part of my effort to write kind of a quirky book, and “a biography of rain” was an effort to draw in that larger audience. So no, I don’t think we should stop talking about climate change or stop using the term. I think there are ways of helping people understand it. These ways are working. I think polling shows that people have better and better understanding of climate change.

Are you optimistic about our ability to adapt to this changed climate?

The amazing thing about the story of rain and humanity is to see how adaptable humans were to the incredible extremes of our climate history, including pluvial periods, which are times of extreme rain such as the Little Ice Age, and the horrors of rain in medieval times, and the droughts that did wipe out civilizations. We still survived those times. So the amazing thing about this story is the adaptability of humans, but what I think is really important is to learn from the past.

We're at our best working together with a sense of purpose and unity, like the linking of national weather stations to forecast weather over telegraph lines in the wake of the Civil War, or even in 1990, when Congress amended the Clean Air Act to reduce the pollutants responsible for acid rain. In the quarter-century since, the market-based cap-and-trade program has cut sulfur dioxide emissions in half at a fraction of expected costs, a great environmental turnaround story. This was a triumph of people. And it’s just the sort of thing we could come together on now to reduce to carbon emissions.

I think the witchcraft story from the Little Ice Age is another cautionary tale, a cautionary tale about denying science in our time. When people were under that stress -- it was climate stress and financial stress -- they became incredibly paranoid and there were thousands and thousands of women executed for witchcraft, specifically for conjuring storms. It’s just the kind of crazy things that human beings do when the going gets tough. So I wanted to tell some of those stories to harken more reasonable times.

Shares