Just as the pun is the lowest form of humor, so is the list the lowest form of literary comment. But puns, at least, can occasionally claim a laugh or two. The book list, and most particularly any list of the "greatest" books, is an exercise that always seems to leave us dumber. Such lists take everything that is exhilarating about a literary experience, everything idiosyncratic and transformative about each reader's unrepeatable encounter with an author, and turn it into a contest, a checked-off task, a quarrel.

But we do love those lists. I'll venture to say that Americans crave them more than most, perhaps because a greatest-books list summons our competitive instincts and meritocratic fantasies. We want our favorites to rank high in the eyes of the world, which in turn confirms that we're better-read and have better taste than a host of imaginary rivals. Hand us a list that denies both of those desires and you're still giving us something we prize: a grievance, and the acrid joy of shaking our fists at the sky, prophets without honor in our own country.

So fierce is our hunger for these pleasures that when the world won't supply us with greatest-books lists, we have to invent them. Presumably that's why Vanity Fair magazine chose the headline "How Harold Bloom Selected His Top 12 American Authors" for a short piece about the octogenarian scholar's new book, when the book, "The Daemon Knows: Literary Greatness and the American Sublime," makes no such claim. Notice the finesse of that "his" -- a word that readers, in their hunger for definitive pronouncements, can be counted upon to replace with "the."

Sure enough, the Vanity Fair piece prompted an angry retort from the site Book Riot, an appealingly populist operation that claims "We geek out on books, embarrassingly so" on its list (yes!) of foundational "beliefs." Contributor Rachel Cordasco, in a piece titled "Our Lists of the Greatest American Authors," explained that "news of Bloom’s book" had "disturbed" Book Riot's staff and provoked much discussion because the 12 writers Bloom examines are all white, mostly male and all wrote before the mid-20th century.

Cordasco admitted that she hadn't read the book, "I just read about it," but she still had a couple of bones to pick with it. First, "if Bloom is arguing that these 12 white (and almost all male) writers represent the pinnacle of American literature, then he needs to return to planet Earth and look around." And, second, "if Bloom is simply trying to define the “American Sublime” in terms of “canonical” writers, then excuse me but snoooooooooooooooooooze because writing a book about Whitman and Melville and Dickinson and Emerson has been done and done and done and let’s move on, shall we?"

This was not Book Riot's finest hour. It's extremely easy to ascertain that Bloom is not attempting to do either, since the second sentence in "The Daemon Knows" reads, "Whether these are our most enduring authors may be disputable, but then this book does not attempt to present an American canon." Rather, Bloom wants to tease out the (mostly) 18th- and 19th-century roots of one of his most cherished literary themes, "our incessant effort to transcend the human without forsaking humanism." Contrary to what Cordasco seems to think, defining the "American Sublime" is not a major concern in literary criticism (although it is significant tradition in American painting), so the ground Bloom covers here is not even especially well-trodden.

Still, part of me wants to second Cordasco's "snoooooooooooooooooooze," albeit with 89.47 percent fewer O's. Emerson, a presiding figure in "The Daemon Knows," has always been a bit too lofty and vaporous for my taste, and while I admire Faulkner (another of Bloom's 12), I often feel that his influence on American fiction has been far from benign. Besides, let's face it, Bloom's antipathy to identity-based literary studies -- what he calls "the School of Resentment" -- is legendary, so if he really were composing a great-books list he would probably pick a lot of the same writers and would almost certainly not give a damn about the complaint that its demographics were insufficiently representative.

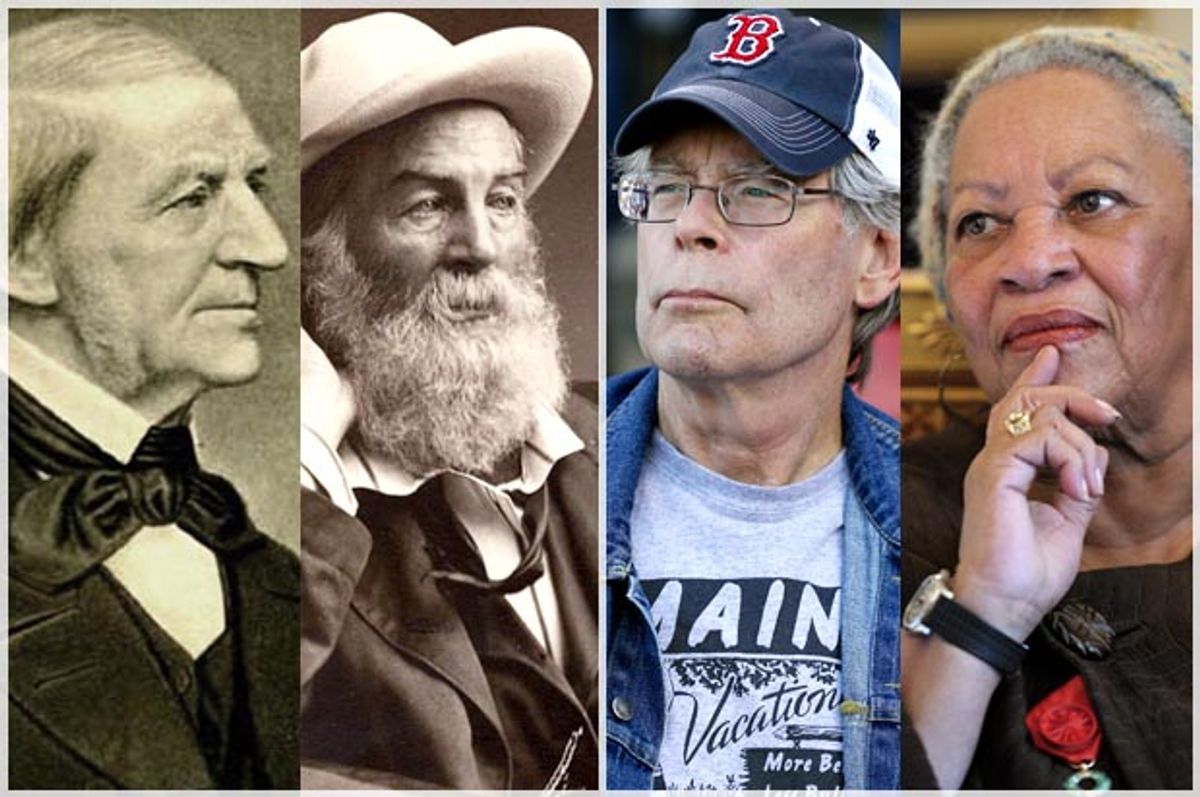

A "snoooooooooooooooooooze," however, can be a double-edged sword. Book Riot's response to what it imagines to be Bloom's provocation is this: 15 lists from 15 different contributors, each consisting of nothing more than the names of 12 writers. The writers listed include Toni Morrison, Dorothy Allison, Margaret Atwood, Junot Diaz, Stephen King and even Stan Lee, all sans context — or even a favorite work noted.

For all the evident sincerity of these lists, this has also, in one form or another, been done and done and done. It's not engaging unless you are the sort of person who likes to argue unceasingly about which books belong on great-books lists, and if you are such a person, I'm very sorry to have to tell you that you are boring.

I confess to having a fondness for both sides of this artificial feud. Bloom's name-dropping, his oracular posturing and his often gaseous prose can be trying, but he has certainly done the reading. ("Of course I’ve read everything," he helpfully confirmed to a fawning interviewer in the Daily Beast.) Plus, I've always suspected that Bloom's saving grace is a sly awareness of how ridiculous he can be, as evidenced by his affection for Shakespeare's Falstaff. Also refreshing is Bloom's refusal to tout reading as a moral enterprise. "You cannot directly improve anyone else's life by reading better or more deeply," he writes in his 2000 book "How to Read and Why." Furthermore, "the pleasures of reading indeed are selfish rather than social."

What redeems Book Riot from its tendency to go off half-cocked and underinformed is its vitalizing enthusiasm. The mystification with which Bloom surrounds the act of reading can resemble the humbug of the cinematic Wizard of Oz. Book Riot, by contrast, cheerfully celebrates reading as something all sorts of people do with all sorts of books for all sorts of reasons. The pleasures of reading needn't always be as rarefied as Bloom insists -- are, in fact, myriad. This kaleidoscopic reality is more fascinating that some critics' efforts to set up an elaborately articulated hierarchy of literary worthiness.

While Bloom, Sterling Professor of Humanities at Yale, has ensconced himself in a fortress of pomp and circumstance, Book Riot plays the scrappy outsider, scouring the terrain for any conceivable shred of snobbery to fuel the warming fires of its indignation. When it comes up short, it's not above chopping up the furniture. This is a war in which the combatants often seem to have more invested in the fight itself, and their own heroic roles in it, than in the territory fought over. While I prefer quite a few of the writers in Book Riot's "Greatest American Authors" lists to Bloom's favorites, it's still vaguely depressing to see them there, where they appear less as individual artists than as ammo, testimonials to the ideological superiority of those who list them. I don't doubt the list-makers truly love these writers, but this is not a meaningful way to pay them tribute.

No list is, whatever its constituents. And if any species of literary conversation is guaranteed to bulldoze the infinite variety of readerly delight, it's the making of great-books lists and the stupid and pointlessly contentious arguments that proceed from them. Without all that, both parties might sooner recognize that they are not really so different. Bloom and Book Riot share something bigger than any of their disagreements: a propensity to geek out on books, and embarrassingly so.

Shares