In the depths of Chicago winter, a young community organizer sat listening to appeal after appeal for help from people who had lost their jobs. It was the same story every time: Good-paying jobs were few and far between, and the government provided little support for those who were not working. In a climate of “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” and individual responsibility, there were few places to turn for help. Community organizations in Chicago tried to fill the gaps, but funding was tight, there were not enough resources to help everyone, and the economy showed no signs of improving. Each person appealing to the organizer was looking for the same thing: a way out of his or her struggles. But the organizer had very little to offer beyond the motto “a helping hand, not a handout.”

One plea was particularly hard. The organizer knew the man standing there, hat in hand. They lived in the same neighborhood, and the supplicant, who had been fairly successful in shipping until he was laid off, did not know what to do or where to turn. The organizer’s instructions were clear—no handouts until all other options had been exhausted. Had the man looked for work elsewhere? Yes. Well, the organizer did know of temporary work on one of the city’s public works projects. The man protested: He had been working a desk job and would not survive hard physical labor outside in the dead of winter. The organizer was torn but remained firm, and the man walked away with details for contacting the project supervisor. The next day the former shipping clerk grabbed a shovel and joined the public works crew, excavating a drainage canal. He worked for two days in the winter cold before he contracted pneumonia. A week later, the man was dead.

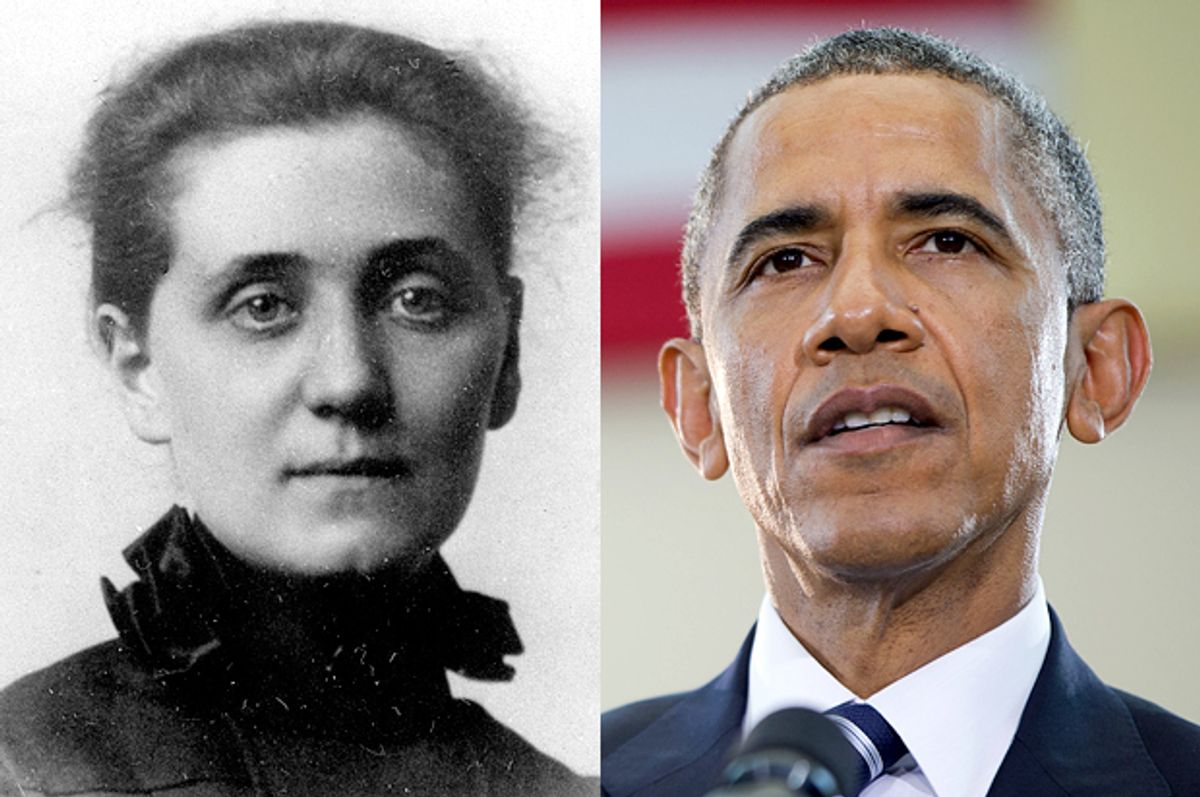

This book is, in part, about the community organizer in this story—one of America’s greatest figures—whose list of accomplishments should sound familiar: Chicago activist, University of Chicago lecturer, gifted orator, politician and elected official, crusader against discrimination, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, and author of one of the most-read autobiographies in America today. Why didn’t this story come up during the 2008 or 2012 presidential elections? Because it happened in 1893, and the Chicago community organizer is Jane Addams.

Addams is best known for founding Hull-House, the celebrated American “settlement house” that served as the incubator for many ideas that would become the foundation of modern social work. How we help people in the United States today is in large part due to Addams’s efforts and thinking in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In simple terms, the settlement was a building, situated in a poor neighborhood, which served as a center for helping people. But it was more than just a physical space. Addams summed up what she viewed as the overall logic of the settlement: “It aims, in a measure, to develop whatever of social life its neighborhood may afford, to focus and give form to that life, to bring to bear upon it the results of cultivation and training.” Young men and women, called “residents,” provided services in the neighborhood, serving as visiting nurses, educators, childcare providers, and advocates. Also, neighbors used the resources of the settlement house, and it was a research center; residents gathered data on social problems with the goal of bringing about social change. Many of the reforms that Hull-House and other settlement houses initiated were geared toward improving the lives of working-class immigrants who shouldered the bulk of the burden of capitalism’s explosion.

Robert Hunter—a sociologist, author, charity organizer, and contemporary of Addams—believed that settlement residents were wired differently. They had, he said, different “habits of their minds,” and the “work of their lives is incited by entirely different stimuli,” like travel, deep introspection, or the influence of strong mentors. Through the settlement movement, Addams and other American women would alter the trajectories available to them and create new paths forward, satisfying their desire for individual growth and their aspiration to help others, and earning them the moniker “Spearheads for Reform.”

Neighborhood Guild, the first U.S. settlement house, was established in 1886 on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Including Addams’s Hull-House, founded in 1889, only four settlements were founded in America before 1890. By 1900 there were approximately a hundred in operation, and by 1910 there were about four hundred. Chicago was home to sixteen at its peak, most notably Hull-House and Graham Taylor’s Chicago Commons.

The American settlement movement also had a strong religious impetus but was not affiliated with any particular faith. The settlement was a church of sorts, allowing residents to worship God through acts in the real world. However, such general descriptions must be used cautiously, as settlement houses were not all the same. Similarly, it would be easy to romanticize the settlement movement and characterize it with more uniformity than it actually possessed; some operated more as religious convents, particularly in smaller cities, while others were closer to the Hull-House model, pursuing social morality in the spirit of the Gospels and of the emerging and distinctly American philosophy of pragmatism. There are still settlement houses in operation today. While they do not have the coherence of a social movement, they are in some places still important outlets for our efforts to help in the community. They serve as lighthouses that draw people in need to safety and support.

The struggle between promoting individual responsibility and helping others in the community was as pressing in Addams’s time as it is today. Resources were equally scarce. For over a hundred years, Americans like Addams have worked to balance the requirements of these competing ideals. Many citizens, then and now, have wondered how to preserve their livelihood, provide for their families, and validate their own hard work, while also addressing the urge—even the moral imperative—to help people less fortunate. For some, like Addams, the answer to this dilemma lies in getting involved in the community and even politics. Indeed, Addams went on to successfully work front stage and behind the scenes in municipal, state, federal, and international politics. But becoming political often requires revisions and compromise in order to get things done. And, certain paths are not always open to particular categories of people in certain historical contexts. Biographies rooted in race, gender, and class (to name but a few) interact with the times to open certain ways and close down others.

This was the case for Addams in the late nineteenth century, just as it was for Barack Obama in the late twentieth century. The parallels between their lives are remarkable. They both moved over and against the limits placed on them by society because of their particular identities. They both began their careers as community organizers and activists in Chicago. Addams settled in the Nineteenth Ward and founded Hull-House, while Obama worked on the South Side of Chicago as a community organizer for the Developing Communities Project. Both became frustrated with the inability to make change outside the political system, got involved in politics, and ran for and won public office. And, as they became political, both Addams and Obama ended up revising their earlier ideals and moving away from their earlier creative work so that they might effect change on a larger scale.

Addams had founded Hull-House as an alternative to the dominant, hard-nosed approach of existing charities. But as she became political, she ended up working closely with these existing groups, moving away from her own more experimental and neighborhood-based roots. She created ties to government officials and Chicago elites, and with these ties came reciprocal demands. They scratched her back, and she had to scratch theirs in turn. She had to be sensitive to and cooperative with one-time adversaries, lest she lose her hard-earned support. At the same time, she felt the pull of the changing times, as women struggled to find their own political voices, independent of men. And, Addams needed to tend to the needs of her family and her own poor health. Not to mention that she had individual yearnings—to read, travel, and enjoy the company of her friends.

For his part, Obama was first elected to public office as an Illinois state senator in 1996. His compromises are better known. In particular, his U.S. Senate campaign in 2004 and his 2008 presidential campaign were full of promises; those who elected Obama did so because they had the hope and craved the change his campaign trumpeted. But quickly, the demands of working with Congress, appeasing donors, and navigating increasingly tumultuous economic waters left many supporters feeling Obama had moved away from—even abandoned— his goals and principles. This showed at times in his successful reelection effort in 2012. But the revisions he made prior to running for office are equally important in understanding his life’s trajectory. Obama worked hard to provide South Side Chicagoans with a voice in the city. But, like Addams, as he worked closely with city officials and elites, he gradually moved away from his more radical and experimental efforts. He was convinced he could not be effective without further education, so he went back to school, then returned to Chicago. All the while, Obama struggled to find his bearings; as a man of mixed racial heritage, the way forward in the post-Civil Rights era was not readily apparent. He had to make his own way.

The shared successes and struggles of Addams and Obama are the subject of this book, but this is not a book just about them. Their stories are instruments to help answer questions about American life: How do Americans act in the face of competing social pressures when trying to help others in their communities? What happens when Americans become political and partner with elites as part of their efforts to move forward? The conflicting social demands of individualism and community assistance comprise a challenge that many face— it’s the American’s Dilemma. Well-meaning people are torn, akin to Goethe’s Faust who bemoaned having two souls beating in one breast. Whether the president of the United States, a registered nurse, or a university student, at some point most Americans wonder how to help others while still working toward the American Dream, how to lend a helping hand and still be a bootstrapping success. We are asked by society to be good workers, to be good consumers and “buy American,” to be healthy, to be good parents, and to be good friends. We also have our own drives, from wanderlust to sitting down on the couch to spend an hour with a good book. Obama and Addams, like ordinary Americans, felt the pull of all these competing urges.

Americans have a fierce spirit of individualism dating back to the nation’s founding. In public discourse and in the home, most Americans hold dear the notion that (for better or worse) each should be left to sink or swim. The United States was built on the idea of classical liberalism, which emphasizes individualism and freedom. The idea of doing it yourself, whatever that may be in practice, is reinforced from every direction by social institutions, including the media, schools, and workplaces. Still, Americans also like to help people. In America’s national culture, there are certain norms that shape social behavior. Most world religions encourage the helping of others in one way or another, and the idea of doing good works is tied to individual transcendence. The engine of faith has driven much of community helping in America. In fact, we will see that both Addams and Obama were influenced by religion. It is also clear that the idea of lending a helping hand is part of the myth and legend of the nation’s founding. Whether the story is of Native Americans helping pilgrims to survive the cold New England winters or of neighbors helping neighbors in the wake of a tornado in Oklahoma, Americans believe that, in a pinch, they will help their neighbors and their neighbors will help them. Sometimes it is hard to adjudicate between the competing spirits of individualism and community. They are, at times, incommensurable.

We are influenced in our decisions about how to be a social citizen by what our parents did—maybe they provided money or time to help people in their community, on their own or through a local church. Or maybe the parents did little community work—they were working too much or didn’t think it was their responsibility. Friends and mentors will have an influence, too. “Make a difference! Get involved!” All this exposure to new ideas can generate excitement, leaving one feeling as if one can do anything with the right attitude. This spirit is captured by the Margaret Mead quote that pops up in greeting cards and on inspirational posters: “Never doubt that a small group of committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”

Still, it is easy to be overwhelmed with the problems of the world. They can leave a person feeling small and ineffective, confused about where to start and fatalistic about what an individual person can actually do. The problems are just so monumental! Admiring and emulating Margaret Mead are different things when there is a paycheck to earn, rent to be paid, or diapers to be changed.

All of this equivocating is part of the American’s Dilemma. It has been with us since our nation’s founding, and, as a society, we have had plenty of time to think about the answers. Often, though, Americans have let such uncomfortable ideas go quietly ignored. The idea of America as a place of incommensurable dilemmas is not new. We are put in difficult positions by competing, but core, American values: “Americans help each other” and “I am responsible for my own success.” The choices we make for moving forward when these values conflict define us as individuals and contribute to our moral development, both individually and socially. What we do is important not just for our own lives, but also for our community values. The most promising social “place” to experiment with ways to accommodate our conflicting values is in relations with others in our neighborhoods.

We all deserve to receive help in times of need, and we may be in a position to help someone else in another moment. Maybe we do it through an organization or on our own. But this help is about on-the-ground, face-to-face relations. It is a back-and-forth process with no end. In a sense, we are building roads that we travel together, and we are acknowledging that there is no destination but a better society. Perhaps this sounds a bit pie-in-the-sky. But Addams and Obama show us that it is possible. They demonstrate that sometimes we get stuck and cannot move forward in the direction we want to go. Limitations made each choose a different path, entering into politics. Rather than continue their initial community work, Addams and Obama revised and scaled up their efforts. Surely, they also left something behind.

* * *

As Tolstoy asked, “What is to be done?” Or put another way, “What is the moral of this story?” It is one thing to show that two individuals have been able to find ways to address their own American’s Dilemma, helping others while finding their own success and happiness. It is quite another to ask that we do the same ourselves. One does not have to run for president or found a new approach to community helping. It is enough to act in small ways, contributing in some measure to the growth of our communities as we move beyond our own contradictions. These actions are to be celebrated. Through an engagement with the early community work of Addams and Obama, I hope to convince the reader of the merits of three things:

Don’t get comfortable. As we go about our daily lives, it is easy to follow the same well-worn paths. But if the stories of Addams and Obama show anything, it is that shaking things up and crossing boundaries leads to interesting outcomes. Be a person of action. Be a boundary crosser. This is easier said than done in the face of serious resistance, but the hardest things are usually those worth doing. And it is not always clear, at least at first, what might have changed as a result of your efforts. An obvious way to go about doing this is to travel. But travel can take place in your own backyard. Go to the “other” side of town, a place you aren’t familiar with, and look for those common bonds of humanity that Addams wrote about.

Look for deeper connections, rather than flitting through life without engagement. In the words of Zygmunt Bauman, be a “pilgrim” not a “tourist.” This is not just about how we actually travel, whether in our own town or across the globe. It is about how we live, how we travel through life itself. Deeper attachments are more sustaining and offer the potential to give you something in return.

And as you move through new situations, take a page from Obama and listen. Don’t try to “tell it like it is” before hearing what people have to say. As we see the size of others’ burdens, we come to understand our own burden in a different way. But moving out of your comfort zone doesn’t mean you have to be completely selfless. Addams and Obama did not stop living their own lives. It is critical to leave space for yourself while helping others.

Connect with your neighbors. One solution to the American’s Dilemma is to try to become grounded in one’s own community and cultivate the “habits of the heart” that were so effective for Addams and Obama. But not just any connection will do—writing a check to a local charity, donating to Good Will, or joining a bowling league (as sociologist Robert Putnam famously described) isn’t enough. Nor is simply engaging in a joint attack of electricity and sunshine in the spirit of a nineteenth-century friendly visitor—that is, pure enthusiasm is not enough. Addams and Obama show us that if the goal is to do good in the world and help others, one needs to step outside and start connecting to people in the neighborhood. One might start by volunteering at a local community center, shelter, or church. This kind of local, small-scale action creates connections to others, and through these connections, as we see in the cases of Obama and Addams, the actor gets back as much as, if not more than, she gives. Learning what neighbors truly need will put one in a better position to do more— and to do it in a way that will make real change for the neighborhood.

Both Obama and Addams show us that communities are something we create, not something given to us. Their efforts to create community show the merits of the idea that “if at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” Community creation is messy and requires constant work as each individual links herself to something bigger. Save for the very wealthy, it would be difficult to follow in the initial footsteps of Jane Addams, who funded her early work at Hull-House out of her own pocket. So, as a society, we might cultivate a research and development space in the American welfare system, one that supports and rewards creative, community-based efforts. Imagine a system in which a future Jane Addams or Barack Obama might receive government funding to start an innovative, community-based program to connect with and to help others. Such funding might be part of an effort to improve the existing welfare system by finding and encouraging local community engagement and fostering norms of reciprocity.

It doesn’t have to be an either/or situation. (This is not a call for another thousand points of light.) We can and should provide basic supports that allow all members in society to live in dignity, and at the same time encourage efforts that build and nurture community growth. Some communities actively turn to their neighbors out of necessity. But in a society with rising inequality and childhood poverty, the overall system is flawed. One way we might improve things would be to look to the best of both Obama and Addams—a system that will incentivize and enable a return to the creative potential of Addams’s time without taking away (or gradually defunding) the safety net and devaluing the social citizenship we have today.

Watch out for selfish reciprocity. As we can see with Addams and Obama, they both chose to become active in politics, but only after building on-the-ground relations with real people in their own communities. Addams and Obama also received support from business leaders, whose money and names made a difference at times. As one begins to make neighborhood connections around helping in the community, it will likely become apparent that many of the problems facing neighbors are structural and require policy changes. This in part is what happened with Addams and Obama. But bringing about these kinds of changes often requires one to step out of the neighborhood and into politics and the halls of power. Money and influence are required.

This is where it is necessary to be careful, because often the world of business and politics is about cronyism and self-interest, rather than a concern for the community. The selfish reciprocity Addams warned us about is a matter of “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.” Nothing comes for free in business and politics. This is not an injunction to avoid electoral politics or turn down a check from a well-heeled businesswoman. Just be cautious.

The point is that once you relinquish your independence from elites, you will probably have to compromise your efforts at community-based helping. Pressures come to bear, and the ability to be creative and experimental is diminished. As we saw with Addams and Obama, at times these elites blocked creativity and experimentation. It is worth remembering that the business of business is first and foremost making a profit, not helping other people. The same is true with electoral politics, which is as much about fundraising and campaigning as governance and policy creation. This is perhaps as it should be, but we should not confuse the goals (and methods) of business or politics with those of building a community.

* * *

Let’s return to the opening scene of the book. What would you do if you held someone’s life in your hands? Imagine a neighbor, someone you know fairly well, coming to you and asking for help. What would you want to happen? Would you want a rigid set of rules and procedures that you could point to? Or would you want more flexibility and room to problem solve? Put another way, how will you balance your hard head and big heart as you face your own future social dilemmas? My sincere hope is that my presentation and analysis of the early efforts of Jane Addams and Barack Obama as community organizers might offer you creative inspiration.

Excerpted from "The Size of Others' Burdens: Barack Obama, Jane Addams, and the Politics of Helping Others" by Erik Schneiderhan. (c) 2015 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. All rights reserved. Published in hardcover, paperback, and digital formats by Stanford University Press. No reproduction, distribution or any other use is allowed without the publisher's prior permission.

Shares