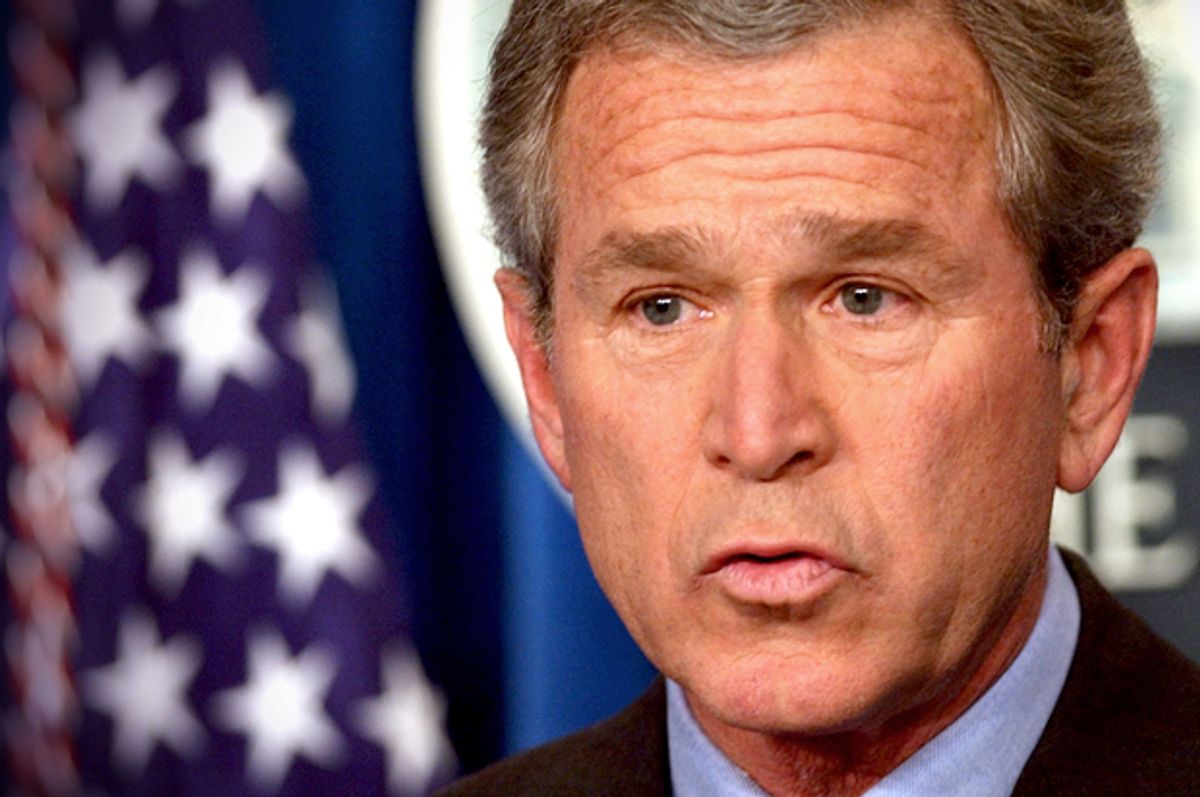

Bemoaning the political climate that enabled George W. Bush's flagrant constitutional abuses and foreign quagmires, Gore Vidal famously dubbed the country of which he fancied himself the official biographer "the United States of Amnesia."

"We learn nothing," Vidal wrote, "because we remember nothing."

A dozen years later, it would hardly seem that Americans have simply forgotten the foreign policy and and economic calamities that defined the Bush era: Voters spurned Mitt Romney in 2012, largely because President Obama argued that however slow and halting the recovery had proven, a Romney presidency would represent a return to the disastrous economic policies of the Bush years. And in a profoundly karmic twist of fate, Bush's younger brother risks failure in his own White House quest, in part because Dubya's presidency has become an albatross. Indeed, if Jeb Bush comes up short in his 2016 campaign, we may date his bid's decline to his erratic attempts to answer whether, in retrospect, he'd have invaded Iraq -- a war a decisive majority of Americans see as a grievous error.

But even if Americans don't look back fondly on the eight years that witnessed a $2 trillion war, claiming nearly 4,500 American and an estimated half-million Iraqi lives; the deepest economic slump since the Great Depression; and the worst-ever jobs record, they're increasingly inclined to cut the man who delivered that list of horrors some slack. For the first time in a decade, a new CNN-Opinion Research Corporation poll finds, more Americans take a favorable view of the 43rd president than look on him unfavorably. Fifty two percent of respondents told CNN they viewed Bush favorably, against 43 percent who did not; when Bush left office in January 2009, those numbers were 35 percent and 60 percent, respectively.

Much of the political press corps pounced on the finding that Bush's favorable ratings are now better than those of Obama, who was propelled to the presidency by a growing anti-Bush backlash. While Americans now view Bush favorably by a nine-point margin, they split on his successor, 49 percent to 49 percent. Of course, it's not surprising that the public is a bit tougher in its estimation of a sitting president, mired as he is in the day-to-day squabbles of American politics. Bush, by contrast, has been out of office for 6.5 years -- and while he hasn't quite grown his hair out and become a hermit, the Lyndon Johnson tradition -- he's assiduously avoided delving into hot-button political debates. Unlike his trigger-happy vice president -- whom we always considered the real brains of the Bush-Cheney politico-policy operation -- Bush seems to understand that the best way to rehabilitate his public image is to lay low.

So Bush's improving numbers aren't some inscrutable mystery. Nevertheless, the findings say as much about us as they do about the former president. We've been reminded, yet again, that our national attention span can be shamefully short. At this juncture, Americans still voice opposition to Bush's foreign and economic policies, but we're maddeningly unable -- or unwilling -- to draw connections between Bush's incompetence and the questions that confront us now. Consider a March Quinnipiac University poll, which found that 62 percent of registered voters supported sending ground troops to Iraq and Syria to fight the Islamic State, which itself was an outgrowth of the sectarianism the Iraq war brought to a boiling point. Yes -- less than five years after the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Iraq, Americans appear little fazed by the experience, and are willing to back another land war in the Middle East. Call it what you will -- the consequence of a state of affairs in which few Americans are directly invested in questions of war and peace; the triumph of the politics of fear; or the return of the Something Must Be Done syndrome that convinced many liberals that the Iraq war was a worthy cause -- but what's abundantly clear is that that we're engaged in a great national forgetting, willful or otherwise. Is it any wonder that hawkish GOP presidential candidates feel comfortable publicly advocating American boots on the ground?

Therein lies the real perniciousness of Bush's (modest) rehabilitation. It's symptomatic of our aversion to wrestling with the lessons of even the most recent American history. Once Iraq proved as catastrophic as the Cassandras had warned, Americans decided they didn't much like Bush's war. But as his misdeeds fade from the public memory, we risk proving the veracity of Vidal's lament -- again.

Shares