When you think about abortion, what comes to mind? A woman’s right? The religious right? Feminists, or fetal photography, or fundamentalists? Do you see the color pink, as in Planned Parenthood, or the color red, as in anger and blood? If you worked in abortion care, the answer probably would be none of the above.

Threats and stigma have forced abortion providers and clinic staff out of the public eye and out of public discourse about abortion, and that—according to providers themselves—is a problem. It is a problem because it has created a political dialogue that has very little overlap with the lived experience of women seeking abortion care and the women and men who serve them.

Pro-choice advocacy frequently invokes terms like "rights," "privacy" and "health." But those who provide abortion care say that this conversation is incomplete at best. It fails to convey the complex values and goals of women (or couples) who seek abortions; it fails to put their childbearing decisions in the broader context of their lives; and it fails to honor the courage, insight, determination, love and compassion that providers witness daily.

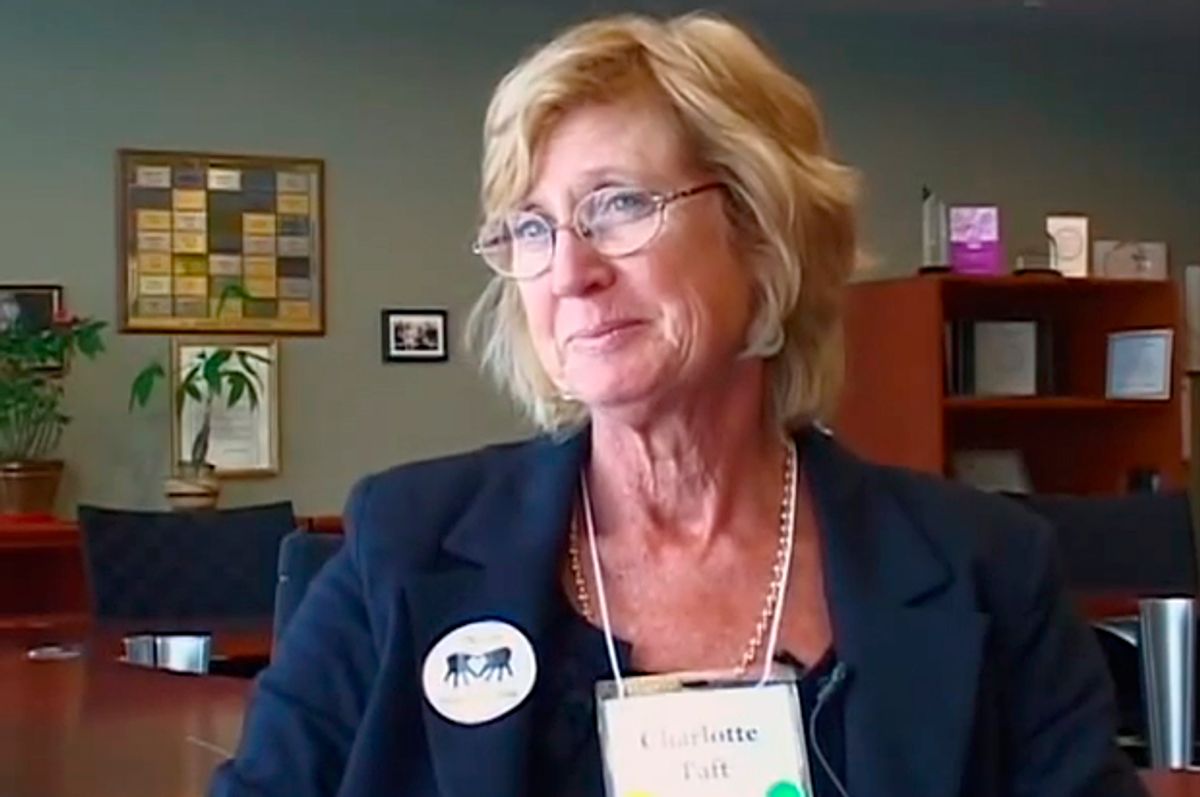

Charlotte Taft is the former director of the national Abortion Care Network. She directed a clinic in Dallas, where she helped to develop a process known as Abortion Resolution Counseling, and for over 30 years she has counseled women through abortion decisions. In this interview she discusses the role of clinicians in advocacy and offers a window into abortion care from her vantage as part of a clinical service team.

Why should abortion providers and counselors have a more prominent place in advocacy? What do they add to the conversation?

The political model of the pro-choice movement over the last 40 years has been based on a concept of rights. This comes from the way Roe v. Wade was argued and decided, but as a counselor I have never worked with a woman who came to a clinic to exercise her right to privacy.

Without exception in my professional life—and I have now worked with thousands of women—the process is a search for the most loving, most responsible, best way to handle a pregnancy when the circumstances of a woman’s life do not support her continuing that pregnancy. So, to me, it is this depth and goodness that is missing in the larger conversation.

You are saying that the political fight about abortion, even on the pro side, doesn’t reflect the reality of women’s lives.

Yes. We focus on abortion as if that were the conversation, but we have been bamboozled into putting our focus there. When we focus on abortion, we miss the actual conversations about supporting women, wherever they may be at.

Fundamentalists want to control women broadly, but in particular they want to control our sexuality and the deep and personal experience of whether and when to have children. Through 40 years of well-funded advertising and organizing, these people have convinced society to take on the understanding of abortion as an evil.

Even our allies are torn. On the one hand we have “abortion on demand and without apology” and on the other we have “safe, legal and rare”—the sense that every abortion is a tragedy. These positions are oversimplified, and they miss the point. Some women are single-minded and clear about what they want, and they just need their self-determination respected. On the other side of the spectrum are women who are deeply troubled and struggling with what to do about their pregnancy.

What abortion providers bring to the political conversation is a recognition of this spectrum and an honoring of the fact that the issue is not abortion so much as it is the reality of women’s lives: What kind of insanity permits the same people who want no access to abortion or birth control to also gut every program to support families, to care for children, to make sure no one goes to bed hungry? How can this level of hypocrisy be permitted? This I still don’t understand.

Tell me a bit more about how you, as a counselor, approach this question in the middle of all the complicated realities of a woman’s life.

The basic issue is that there is a pregnancy and the woman is deciding whether she will welcome, tolerate or say no to it. These basics are simple to describe, but it is a very complex decision, almost always involving paradox, in the sense that within that circle are experiences of grief and relief. There can be joy of knowing that it is possible to get pregnant and at the same time the clear recognition that it’s not the right time to bring a life into the world. There can be anger at what is missing in our culture, which can be a part of why a woman chooses to end a pregnancy. There can be grief, because we are talking about death, about not carrying a life forward, and we don’t know how to talk about the ending of life in a way that honors life. There can be many, many layers of experience.

The clinic that I ran in Dallas for almost 20 years pioneered what came to be called Head and Heart Counseling. Being sure that you want an abortion can be a head decision; you can sign the papers and pay your money without ever connecting with where your heart is about the choice. But we saw that abortion was more than just a medical procedure—that if we were just providing medical care we were missing an opportunity to be with women in a way that helped them heal and grow and feel their own wholeness.

If a counselor was working with a woman and had a sense that she was not prepared for an abortion that day, we invited her into a process. We never said you are not ready for an abortion, because that is a judgment. We said, from the conversation, we are not prepared to provide you with an abortion today.

This was quite a process. We used a triage form designed to help identify which women were clear and confident about their choices and which women had significant choices that they needed to work through as part of coming to a sense of resolution.

By sense of resolution, I mean that her heart breaks open wide enough to accept those contradictions that I was talking about. I mean that she can forgive herself for being human; that she can on most days remember her goodness and courage; that she can stand the days that she might feel guilty or bad; and that she will understand in her gut the complexity of her choice to not bring new life into the world and in fact to end life. This is controversial even within the pro-choice movement because we don’t know how to talk about the life and death part of abortion.

Can you tell me a story that for you illustrates this process?

One day I was called to be the second person in a counseling session. The counselor said, “This person seems extremely flat affect. I can’t connect with her. I don’t know what she wants. I can’t get a feel for her.”

It was a woman in her mid-20s, and I could immediately see what the counselor was talking about. She was looking down at the floor, not making eye contact—didn’t seem really present in the room. I said to her, “If you were an animal right now, what animal would you be?”

And she looked me in the eye and said, “I would be a dead squirrel.”

And I said, “That explains a lot. We can’t ask a dead squirrel to make this kind of important decision.”

And she laughed and became present. She told me she was feeling very ashamed of having become pregnant and not married. Her biggest issue was that she was very close to her parents but she felt too ashamed to tell them about this pregnancy. We catalogued the losses—her own sense of goodness, her sense of being a smart woman, her hope of a relationship with the man, her connection with her parents, which was so essential to her.

At that point, our conversation split into two parts: First, I gave her a workbook we used to help a woman go through her deepest beliefs about what an abortion is and how it would affect her, and I explained, “If you would like to get services at our clinic this is required homework.” Second, I asked, “If you told your parents, what would that be like? How would you do it? What would it take from you? What kind of qualities would you have to bring forward in order to do that?

We rescheduled her for Saturday, which was several days in the future so she had time to do the homework. The day she came back, she told me that not only had she done the homework, but her father was with her and her parents were extremely supportive. She said, “I didn’t just take on the question of abortion, I took on my whole life.”

As I was holding her hand during the procedure, I asked, “What kind of animal are you today?” And she said, “Today I am a lioness.”

My calling, my life’s work is to midwife the process through which a woman finds her lioness. Abortion has been the context in which I have done that. There are other situations in which women do that and other kinds of providers who help—actual midwives, for example. But abortion is a unique juncture-- death and life and power, I don’t know where else that concept of crisis, meaning danger and opportunity, exists to such a degree—the potential for a woman to choose herself in a way that she may never have done in her life. That is part of what has kept me in this work for more than 30 years, the opportunity to experience that kind of transformation.

How did you get into doing this kind of care?

In 1962 when I was 12 years old, a Romper Room school teacher from Phoenix, Arizona, had an abortion after much political and legal wrangling, and it was in the news. Her husband had brought back an anti-nausea drug from Europe that turned out to be thalidomide, which causes children to be born without arms and legs. When she realized this, she sought an abortion from the local hospital.

In those days there were panels of doctors who got to decide: Were you really suicidal? Was your situation bad enough to warrant permitting an abortion? In this case, the panel decided yes.

The woman felt it was important for other women to know the dangers of this drug, so she did a newspaper interview. When the hospital saw that she had done this interview, they decided to revoke her permission. She went to court to petition for the right to abortion, but it was denied. She ended up flying to Sweden.

This was in the news, and it was a conversation that my mother and I had about how terrible it was that she wasn’t able to make her own decision and that the media were out on the lawn when she was trying to take care of her life and her family. That is my very first remembering of the issue of abortion in my life.

Later, as I grew into adulthood, there were times when someone needed an abortion and didn’t have the money and I had a little money ... Unwanted pregnancy was always in the backdrop of women’s lives. When I moved to Dallas I was in a TV interview talking about the politics of abortion. Afterwards a friend who also was interviewed said, “You should apply for a position at our clinic.” I did apply for the job, and they put me in the room of someone having an abortion, and I fainted. I was afraid I had made it dangerous or something, but the patient was fine and they hired me.

And then you stuck with it for 40 years.

I found that that work brought together everything I cared about. I was a feminist. I cared deeply about not just the rules and the laws but the internal experience, how women saw themselves in their lives. Also, I was very interested in how is this done? Are we doing the safest, the best?

In 1978 some doctors from that clinic and I opened our own clinic. That was my opportunity to put everything I believed into effect. Western medicine has never seen the emotional/spiritual heart of a person as an important element of medical care, but I believed from the beginning that excellent abortion care was a marriage of excellent medical care and feminist respect for women. We were there at one of the most vulnerable and potent points in many women’s lives, and we could midwife the shift in which a woman moves from being a victim to taking charge of her own destiny.

You had these—almost spiritual aspirations, if I can call them that—but at the same time you were in the trenches. During those years, the religious right was gearing up protests and even violence against clinics and providers.

We had Butyric acid thrown, Operation Rescue, threats. But what we didn’t have were the brilliant tactics of abortion opponents today of making it almost impossible to provide abortion care. These new laws that apply only to abortion providers could not exist except for the supermajorities in state legislatures.

The years since 2010 have brought challenges that make excellent, whole-person care virtually impossible. When you require a medical center to expend large parts of its energy and budget on shenanigans, time and money that could be going to patients, the clinic team simply cannot take the time to provide the kind of in-depth counseling I just described. For many of my colleagues that has been a terrible struggle. To try and bridge the gap, I created a downloadable counseling workbook, but it is impossible for clinics to provide the level of service they would like to provide.

I think that the public has no idea of what has been lost. No one understands that small clinics are trying to figure out how to provide excellent care without being able to collect the fees. If they are serving women who are underemployed, insurance may not be available. The cost of a first trimester abortion has increased by $17/year since I started my clinic in 1978. What gets cut is the counseling.

How do you see the role of men in all of this?

It goes without saying that every unintended pregnancy involves a man. Much of the time men are involved in abortion decisions, which are made as a couple. But the focus on women and rights has excluded men from many conversations about reproductive empowerment. We talk disproportionately about abortion in the context of rape, because we feel we can’t talk about more ordinary unintended pregnancies. But I don’t want to live in a world where women, broadly, are framed as victims and men as perpetrators. We really need to engage men more deeply around their own parenthood desires. What kind of life does a man want to have? What happens after a pregnancy, whether it is carried to term or not? How does he feel about himself? Where is he in the actual experience of raising a child?

Also, we should have better contraceptives, as in we really need contraceptives in the beer. What percent of men who no longer wish to parent are getting vasectomies? That conversation has totally disappeared.

You said earlier that when we focus on the abortion procedure we are “bamboozled.” That abortion itself is the wrong focus if what we’re really after is honoring and empowering women and families.

Abortion is the hole in the doughnut. The doughnut is the woman’s life. We focus on the hole instead of the life.

The women seeking abortions fall into two categories: In one are the women who don’t want to carry forward a baby (or often, another baby). In the other are women who say, “If I won the lottery I would love to have this baby.”

I sometimes ask, “If you had a magic wand, what would you do?” For women in the first category, that takes them back before they were pregnant. But others talk about changing their circumstances so they could make it work with a baby. When that happens, I say, “It sounds like you would really like to have this baby—let’s see if that might be possible for you.”

That’s where broader gender and justice concerns become a huge factor. In a just society, children wouldn’t go to bed hungry. People would have safe housing. Men would not be permitted to rape women. Women are reaching to get out of poverty, to take care of the children they already have.

I wish that we talked about “choices” instead of “choice.” Because when a woman has an abortion, she isn’t choosing the abortion itself, she is choosing an education, or military service, or her loyalty to the family she already has.

Sometimes an abortion feels like a sacrifice—I’m giving this life up to honor these lives that are already here, including my own. Often it’s not a matter of giant aspirations; it’s just that she can’t add this and maintain her life. It doesn’t feel very heroic sometimes--but which man would all of a sudden want to give up his life?

What do you wish most that you could say to advocates who aren’t involved in clinical care?

It would go back to the conversation about goodness. This is the missing element. We talk about rights, we talk about rape—much of our language either victimizes women or makes them seem hard.

I don’t believe that one decision or the other is good—whether a woman chooses to have a baby and work with whatever that looks like for her, or whether she chooses to have an abortion. That is none of my business. What is my business is that she has a process that allows her to experience her courage and her goodness. Afterwards, when the stigma is there both on the inside and the outside, having been through that process gives her something crucial.

It takes courage to face your life and make a responsible decision about whether or not you can bring a new life into the world. The goodness lies in the deep respect, not just for life but also the understanding that if you have a baby that child is a human being that deserves attention and nurturance. The goodness lies also in being able to say I don’t want to do that or I just can’t – that is goodness, regardless of the decision.

What would it take to change the conversation?

Change happens when things affect the people in charge. Imagine if a pregnancy test routinely includes a paternity test. It would make the invisible man instantly visible. You would have instant financial obligations.

Change happens also when you turn on the lights. Every place that the lights are off, wherever there are topics we are afraid to talk about, there’s potential power in that. Consider, for example, that a larger and larger percent of women having abortions are women of color. Let’s have that conversation: Why is the rate of unwanted pregnancy so much higher among women of color? What are the pressures and barriers at play? The right hears our silence and uses it to imply that abortion advocates have a racist agenda. Let’s talk about that.

Change happens when technologies change. Long-acting contraceptives like IUDs and implants now offer a powerful choice for young women who want to manage their childbearing. Young women couldn’t afford these methods before and, at least in some places, now they can. Some communities are wary, because in the past sterilizations sometimes were forced on women by an external “them.” But imagine empowering real choices through truly excellent pregnancy prevention and abortion when needed. Imagine a young woman being able to say I chose my childhood. I’m choosing the children I already have. I choose myself. A lot of times a woman has been taught never to choose herself. That is forbidden, and even if she does it she can never tell anyone. Imagine changing that.

Change happens when people band together to take care of each other. Where did sisterhood go in the women’s movement? We got a job and we lost each other? Talking about your abortion if you can is not just standing for yourself, it’s standing for other women. Where did that get lost?

Change happens when people are willing to pay a price. In this country it has been a very long time since there was real civil disobedience with a price to pay. I don’t think this thing is going to change without real civil disobedience. Where is the no going to come from? Where is the guy with the shopping bag standing in front of the tank? Who is he among us? And what do I need to do to look back at the end of my life and say, I did what I needed to do.

Shares