At the turn of the last century, the “Wisconsin Experiment” led the nation as a way to develop government policies that would promote the greatest good for the most people. Gov. Robert La Follette brought together government officials, university professors and business leaders to hash out intelligent state policies.

Today there is another Wisconsin Experiment underway. This one, though, is designed to tear apart that broad civic vision and replace it with an oligarchy.

On its face, today’s Wisconsin story appears to be about budgets and entitlement. Citing the need to save money, the Joint Finance Committee of the Wisconsin Legislature at the end of May voted 12-4 to cut $250 million from the university’s budget and eliminate tenure from state law, enabling the governor-appointed Board of Regents to fire professors whenever they declared it time to “redirect” a program. Opponents are focusing on the end of tenure, but there is a larger story here about money, politics and ownership of the national government.

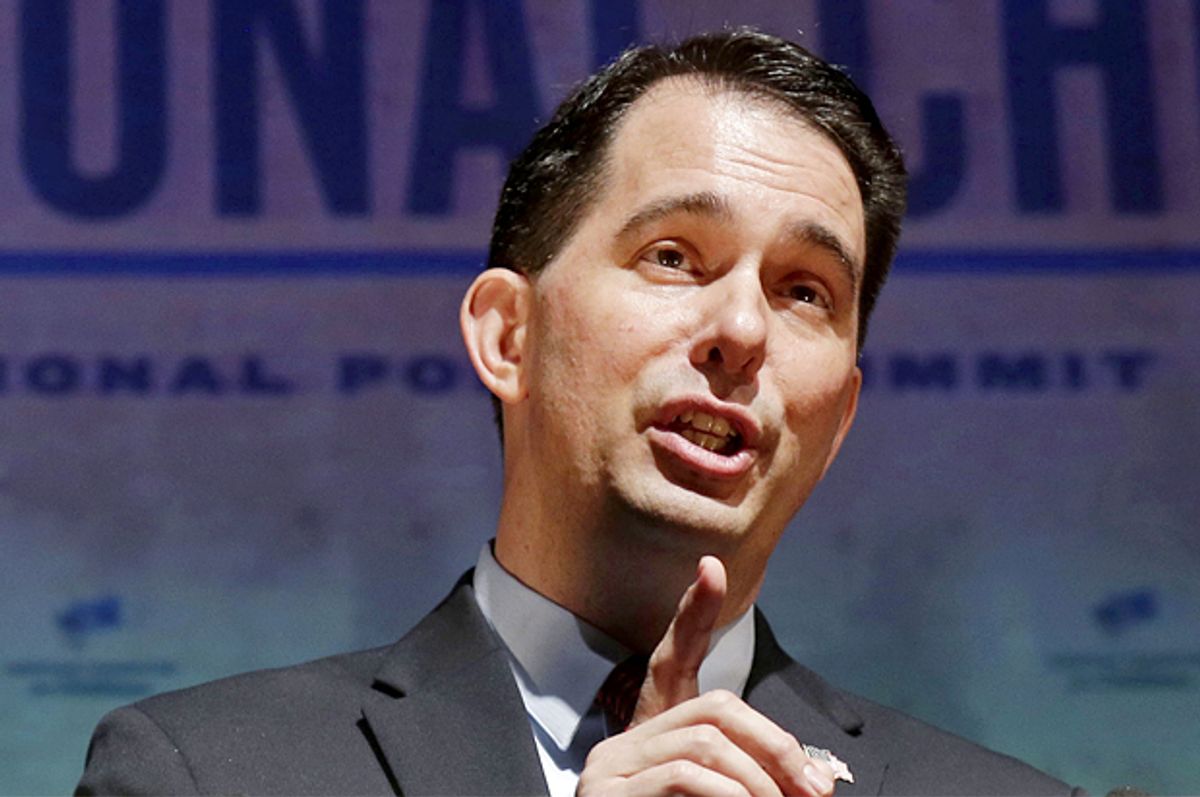

Significantly, Walker has referred to the measure as “Act 10 for higher education.” Act 10 was the 2011 Wisconsin Budget Repair Bill, passed by the Republican Legislature at Walker’s urging. It was the measure that created such furor in early 2011, as tens of thousands of protesters converged on the Wisconsin Capitol, Democratic senators fled to Illinois to stop a vote on the bill, and Republicans finally found a loophole in the quorum rules that enabled them to pass the measure without their Democratic colleagues.

At stake in this bitter fight was the nature of American government. Should workers have the right to bargain as a unit, joining together as a political bloc to influence both their contracts and government policies? Or should they be forced to compete for national power as individuals equal to the wealthiest men in America?

FDR and a Democratic Congress first established workers’ right to political organization in 1935 with the National Labor Relations Act (also known as the Wagner Act). They saw collective bargaining as a way to guarantee that the government served everyone, rather than the very wealthy who had led the nation into the Great Depression. Collective bargaining would level the playing field between workers and employers in politics, guaranteeing that government policies would benefit everyone.

But from the moment of its passage, Movement Conservatives insisted that the Wagner Act perverted the government by giving workers too much power. They must not be able to work as a unit; they must stand alone as individuals, just as wealthy men did. If workers could join together, they would influence workplace conditions and government policies. Undoubtedly, government regulations would establish minimum wages and maximum hours, and require costly safety measures. These would inhibit the ability of employers to make money and therefore, Movement Conservatives insisted, amount to a redistribution of wealth. The ability of unions to exercise political power was a fast track to communism.

As soon as Republicans regained control of Congress, they curtailed the Wagner Act with the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, limiting workers’ ability to strike, preventing unions from donating to national political campaigns, and requiring labor leaders to swear they were not communists. When President Truman vetoed the measure, they passed it over his veto.

Movement conservatives were only beginning their attack on the power of workers in government. In 1951, William F. Buckley Jr. brought the fight against government regulation to universities. His "God and Man at Yale" complained that because professors at Yale—one of the most conservative schools in the country—advocated government regulation of the economy to protect workers, they were “thoroughly collectivistic.” While they were not actively calling for the overthrow of capitalism, he explained, that was their ultimate goal: they were calling for “extended social services, taxation, and regulation to a point where a smooth transition could be effected from an individualist to a collectivist society.” They were corrupting America’s youth.

Three years later, Buckley identified these collectivist academics by a new noun, capitalized to suggest they were part of an international cabal that mirrored Communists. They were “Liberals.” By definition, any professor who believed that the government had any role in protecting workers, rather than defending the rights of property, was part of “liberal academia.” Liberal professors were destroying America by ushering in communism.

In 1958, Movement Conservatives in seven states ran for office on right-to-work platforms that would break the unions. Their ideas were so laughably unpopular that they lost decisively in six of those states. But in Arizona, voters reelected Sen. Barry Goldwater, who had made it his mission to destroy the political power of unions. They were destroying human freedom, he insisted, and were “more dangerous than Soviet Russia.”

Goldwater became a Movement Conservative standard bearer, and his stance got national attention with the 1960 publication of "The Conscience of a Conservative," ghostwritten by Buckley’s brother-in-law L. Brent Bozell, but published under Goldwater’s name. This slim volume announced without a hint of irony that unions concentrated mammoth political power in the hands of a few men, and thus irreparably corrupted the political process. The only way to restore American freedom was to remove unions from politics, and make sure that individuals alone could make financial contributions to political campaigns.

Goldwater’s manifesto was elitist—it reminded readers that education was never intended to “educate, or elevate society,” but to educate individual leaders “to take care of society’s needs”—but it did not expressly attack universities. It took John F. Kennedy’s election to link unions and higher education in popular political rhetoric. Republicans horrified by the election of a Democrat insisted that Kennedy had won only thanks to the support of organized labor, and harped on his Harvard education and his Ivy League brain trust as proof that liberal academics were ruining America. Then Kennedy issued an executive order giving public employees collective bargaining rights much like those accorded to private employees under the Wagner Act. It seemed to prove that liberal academics were bringing communism to America by handing political power to workers.

In 1964, Ronald Reagan articulated a growing distrust of liberal academics in his televised prime-time speech in support of Goldwater’s presidential bid. Reagan’s “A Time for Choosing” attacked the social welfare policies of Kennedy and President Johnson as leading to “the ant heap of totalitarianism.” Reagan warned against “a little intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol” planning the economy and, for good measure, took a potshot at a Harvard education. Two years later, Reagan won the governorship of California, thanks to his fire-breathing promise to “clean up that mess in Berkeley,” where students were falling under the sway of left-wing agitators and protesting the Vietnam War.

Movement Conservatives made Reagan’s anti-intellectualism an article of faith. Although George W. Bush held degrees from both Yale and Harvard, his supporters portrayed him as an outsider from Texas, cutting brush on his newly purchased Texas ranch. Movement Conservative personalities increasingly made whipping boys of members of the “liberal academy,” with hosts like Rush Limbaugh claiming that leftists professors were conditioning people to accept collectivism by “taking hold of the education system, the university, academia system.” Gradually, Buckley’s premise took hold: that universities were, by definition, not places where scholars who believed in a wide range of roles for the federal government in society taught their research. Universities were nests of socialists.

Walker’s Act 10 for higher education is not just about tenure. Its attack on the university that gave birth to the original Wisconsin Experiment is the logical outcome of eighty years of maligning universities as hotbeds of socialism in an attempt to undercut workers’ influence in government. It is a decisive power play in the struggle over the nature of the American government. Should workers have political power, or should a few rich men alone determine government policies? Walker’s stand is clear. He has long worked in lockstep with ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, through which corporations write legislation that goes to legislatures for approval. He is backed by the billionaire Koch brothers, who have indicated they would like to see him in the White House.

If they get their wish, today’s Wisconsin experiment will, like its predecessor, determine the direction of the nation. This time, though, the direction will be toward the greatest good for the wealthy few.

Shares