It seems as though every few months I come across another article trying to explain why the Citizens United ruling, while disturbing in many ways, is not the reason for the explosion of the Super PAC or the recent surge of wealthy billionaires involving themselves directly in political campaigns. The most recent comes from free speech advocate Wendy Kaminer in the Boston Globe, who writes:

Super PACs are not dependent on corporate funding. They’re primarily funded by super-rich individuals, whose right to devote unlimited amounts of their own money on independent expenditures (those not involving direct contributions to candidates) was confirmed by the Court in 1976, in Buckley v. Valeo. As the Brennan Center, a fierce critic of the Citizens United ruling, has acknowledged, “the singular focus on the decision’s empowerment of for-profit corporations to spend in (and perhaps dominate) our elections may be misplaced.”

I’m not suggesting that the great majority of Americans who agree that money has “too much influence” in elections should be relieved that a handful of multibillionaires instead of for-profit corporations exercise that influence. But I am saying the Citizens United decision is not the source of all campaign finance evils.

When Citizens United came down many people believed it would unleash a torrent of corporate money into politics and that hasn't yet happened. Because of the disclosure rules, corporations that have tried to involve themselves in political campaigns have found that it can hurt the bottom line. This happened to the Minnesota-based Target back in 2010, when their board gave $150,000 to the Republican running for Governor and his anti-LGBT stances prompted a boycott threat. The corporation, which has generous LGBT policies, explained that it wasn't done as a measure of support for the candidate's position on social issues but for purely on an economic reasons -- but it didn't matter. The lesson was clear: Corporate support for political candidates could cost a company its customers. (One assumes they realized it was safer to simply pour that money into lobbying as they've always done before to get the same results.)

In her Boston Globe piece, Kaminer pretty much throws up her hands and says that there's nothing new under the sun; the rich will always run the show one way or the other and that's just the way it is.

Some time back, Matt Bai of the New York Times magazine wrote a piece similar to Kaminer's, in which he likewise explained that Citizens United wasn't to blame for the campaign-cash firehose that was pouring into our politics in recent years. Unlike Kaminer, Bai told us that the real culprit in all this billionaire spending did stem from a specific legal case -- just not Citizens United.

Bai wrote:

You may remember that back in the ’90s, the most nefarious influence in politics emanated from what was then called “soft money” — basically, unlimited contributions from rich people, corporations and labor unions to both major parties. According to data from the Center for Responsive Politics, in 2000, the last presidential year in which soft money was legal, the two parties raised more than $450 million of it, divided almost equally between them. Only 38 percent of that came from individuals.

That all changed with the passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, popularly known as the McCain-Feingold law. The new law stamped out soft money for good, but it also created a vacuum in political fund-raising. The parties could no longer tap an endless stream of soft money, but thanks to the advent of the 527, rich ideologues with their own agendas could write massive checks for the purpose of building what were, essentially, shadow parties — independent groups with their own turnout and advertising campaigns, limited in what they could say but accountable to no candidate or party boss. Wealthy liberals like Soros and Lewis, along with groups like MoveOn.org, were the first to spot the opportunity. All told, wealthy liberals spent something close to $200 million in an effort to oust George W. Bush in 2004, setting an entirely new standard for outside spending.

As is his wont, Bai emphasized the fact that "both sides do it." Looking down the road at the even bigger push by right-wing billionaires in the face of a liberal president in the next two elections, Bai concludes that the whole thing is just another aspect of partisan politics in which the billionaires of the "out" party will inevitably put their wallets together to oust the opposition. He doesn't seem to see this as a problem.

And this piece by Lawrence Lessig (in which he announced his 2014 campaign finance reform Super PAC, which ultimately produced what he felt were disappointing results) places the blame on yet another campaign finance ruling:

In March, 2010, three months after the Court had decided Citizens United, one of America’s greatest circuit court judges reasoned that if rich people could spend as much as they want independently of any political campaign, they should also be free to contribute as much as they want to any independent political action committee. “Independence” became a new First Amendment shield; so long as your activity is not coordinated with a political campaign, your activity — whether speaking or spending or contributing — cannot be regulated.

This was the SpeechNow v. F.E.C. case, and based on its reasoning, the Federal Election Commission created the SuperPAC: With a simple letter and a couple-page form, anyone is free to establish a SuperPAC. That SuperPAC is then free to accept unlimited contributions, and spend whatever it collects, so long as it does not coordinate with any political campaign.

Lessig believes that the Super PAC, with its billionaire donors willing to write extremely large checks, is making it so that candidates are essentially running (and eventually governing) as agents of these big-money contributors.

But that brings us back to Kaminer who told us that individuals have been able to spend unlimited sums on independent expenditures since the Buckley vs Valeo case in 1976. So why was the advent of the Super PAC such a watershed? The level of "independent expenditures" went up enormously after the ruling. And just like before, there are rules against coordination between the Super PAC and the candidates, which are notoriously unenforced and laughably ignored.

Basically, if rich people had wanted to do this before McCain-Feingold, before Citizens United and before SpeechNow vs F.E.C., they could have done so. But as all three of these articles point out, it wasn't until the mid-2000s that this started to become commonplace. And it wasn't until the late 2000s that the flood of money really started to gush. Election law expert Rich Hasen wrote that if this had nothing to do with Citizens United, it was a hell of a coincidence. After all, as Bai pointed out, there had been movement in this direction for some time, going back to all the soft money days in the 1990s. (Remember the Buddhist Temple kerfuffle?) There doesn't seem to be any other logical explanation for the sudden explosion after the two 2010 rulings came down.

But still, you have to wonder, if these rich guys could always spend as much as they liked on independent expenditures, what did change? Both Hasen and Lessig speculate that rich donors may not have wanted to make ads that said "Paid for by Foster Friess," because it would have been socially dicey; so they prefer to give the money to a Super PAC where the ad says "Paid for by Americans Who Care About a Prosperous Future" instead.

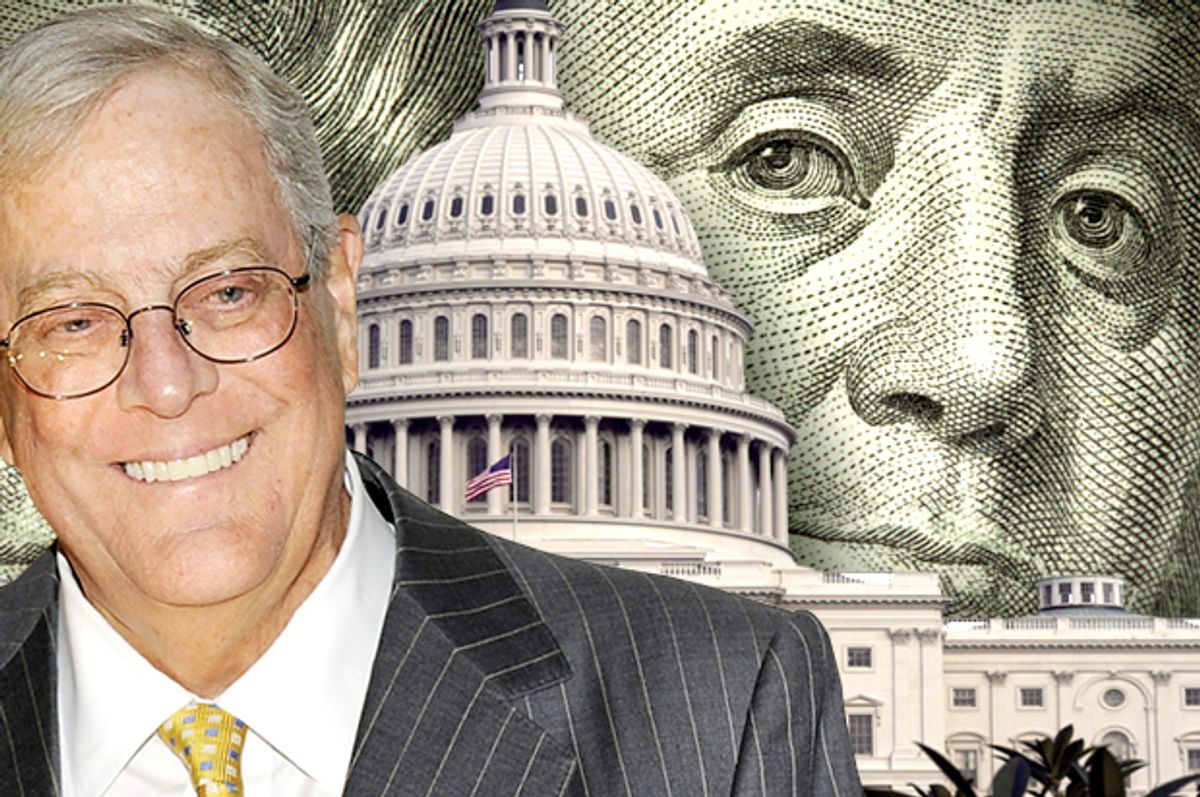

But this doesn't make any sense to me. The press looks at these Super PACs and reports on all the big donations. Everyone knows who the billionaires involving themselves in political campaigns are. In fact, candidates on the GOP side are making frequent and extravagant public pilgrimages to kiss the rings of these billionaires in hopes that they might land themselves a big fish who will either start his own Super PAC for the express purpose of backing the candidate or join up with an existing Super PAC that's been formed to support a particular candidate. Either way, we all know who they are, so this idea that the rich didn't want to be seen getting their hands dirty and these recent cases have given them a less obvious avenue to get involved doesn't really wash.

But perhaps there is another reason, and it has as much to do with the financial meltdown of 2008 as it does with Citizens United. There may have once been a time when the wealthy only wanted their names on university libraries and hospital wings, but the 2008 economic earthquake brought a lot of attention and criticism down on the heads of the 1 percent. And the 1 percent doesn't like it. In fact, they hate it.

For years America's wealthiest have whined and kvetched

Regardless of the motive there is little doubt this phenomenon is distorting our democracy. Sure, the wealthy have always had outsize influence and access. But now they are openly buying politicians, telling them what they expect in return for their money and daring the rest of the country to do something -- anything -- about it.

Unfortunately, while laws, reforms, regulations and oversight would all be welcome, it doesn't look like any of that will fix this, even if the court were to radically shift direction. The problem is that these people have such obscene amounts of money. Until income inequality is adequately addressed, it is likely that our elections will be battles of the billionaires with the crowd (which is to say the voters) basically just cheering from the sidelines.

Shares