Rock and roll is absolutely filled with stories of heartbreaking and all too often horrific tragedy. Like so many creative artists, musicians are often sensitive and not infrequently, troubled figures who express pain as well as brilliance with their output. The business of music, conversely, is often brutal, crushing the spirits and souls of those who do its heavy lifting for profit. Stories of suicides, addiction, overdoses, pain and enduring depression, alongside freak accidents -- terrible and unforeseen incidents that almost inevitably happen while on the road -- fill the pages of rock history. This is not an attempt to name them all -- you will not find all the members of the 27 club, nor the names of the countless individual brilliant artists the music world has lost here. This is neither to diminish their deaths or their music. This list, more specifically, focuses on the sad stories of entire bands -- those who have lost multiple members, their lives taken -- or in one case, wholly consumed -- by tragedy or trauma.

Rock and roll is absolutely filled with stories of heartbreaking and all too often horrific tragedy. Like so many creative artists, musicians are often sensitive and not infrequently, troubled figures who express pain as well as brilliance with their output. The business of music, conversely, is often brutal, crushing the spirits and souls of those who do its heavy lifting for profit. Stories of suicides, addiction, overdoses, pain and enduring depression, alongside freak accidents -- terrible and unforeseen incidents that almost inevitably happen while on the road -- fill the pages of rock history. This is not an attempt to name them all -- you will not find all the members of the 27 club, nor the names of the countless individual brilliant artists the music world has lost here. This is neither to diminish their deaths or their music. This list, more specifically, focuses on the sad stories of entire bands -- those who have lost multiple members, their lives taken -- or in one case, wholly consumed -- by tragedy or trauma.

Here are seven of the most tragic band stories in modern music.

Lynyrd Skynyrd. I don’t blame Lynyrd Skynrd for writing Free Bird, a towering anthem identified as one of the 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Instead, I blame douchebags for making it their drunken, sarcastically shouted mantra at concerts the rest of us are trying to enjoy. An earnest ode to the late Duane Allman, the song, along with Skynyrd’s numerous other hits, have become so firmly part of the rock canon it’s hard to imagine they ever didn’t exist. Founded in 1964, much of the band’s music halted in 1977, when a chartered flight carrying the band to a concert at Louisiana State University ran out of fuel. An emergency landing by pilots failed, and the small aircraft instead crashed in a Mississippi forest. Among the casualties were frontman Ronnie Van Zant, guitarist and vocalist Steve Gaines, as well as Gains’s sister, backing singer Cassie. The wounds to other members were many and extensive. Just three days prior to the crash, the band’s fifth album, Street Survivors, was released. The album yielded two hit singles ("That Smell" and "What's Your Name") and reached number 5 on the charts. The LP’s artwork, which originally depicted the members surrounded by flames, was amended to feature them against a simple, solid black background in order to respect the dead. That artwork was restored three decades later when a deluxe edition of the LP was released.

Yellow Dogs. A band of Iranian ex-pats, Yellow Dogs had moved to Brooklyn to play music without persecution. In Tehran, they -- along with others in the city’s small music scene -- were labeled outlaws simply for being in a rock band; though their songs weren’t about political topics, the act of making music was inherently political. With the move to New York City, they’d gotten modest attention, playing the city’s mainstay venues and opening for bigger acts.

On the morning of November 11, 2013, Ali Akbar Mohammed Rafie -- a musician from another Iranian band that had also relocated to Brooklyn -- crept into the apartment Yellow Dogs shared, and fatally shot guitarist Soroush Farazmand, his brother, drummer Arash Farazmand, and Ali Eskandarian, a friend of the band. Sasan Sadeghpourosko, another friend, survived, but was shot in the arm. Following the rampage, Rafie turned the gun on himself, committing suicide. Yellow Dog’s manager, Ali Salehezadeh, said the original issue between the band’s members and Rafie had been a “very petty conflict.”

The Exploding Hearts. Guitar Romantic was a bit of an instant classic when it was released in 2003 -- the kind of album you fell in love with if you preferred 1970s outfits like the Buzzcocks, Undertones, the Boys, and the Breakaways to what was then being marketed as “pop punk.” Unfortunately, it would turn out to be the Exploding Hearts’ only full-length release. In July of the same year, while driving back to their hometown of Portland from a gig at San Francisco’s Bottom of the Hill, the band lost control of their tour van and experienced a terrible crash. The accident killed singer and guitarist Adam Cox (23), drummer Jeremy Gage (21), and bassist Matt Fitzgerald (20), believed to have briefly fallen asleep while at the wheel in the moments just before the accident. Guitarist Terry Six (21) and the band’s manager, Rachell Ramos (35), were the only crash survivors. Though short lived, the Exploding Hearts’ legacy has been long, centered on an album that is both an homage to blissful power pop, old school punk, and a timeless collection of exceptionally crafted songs.

The Bar Kays. Though they began as studio musicians for the legendary Stax label, the Bar Kays became a notable act in their own right following the release of the now iconic single “Soul Finger.” The same year, singer Otis Redding requested they serve as his backing band on a tour of the country. What must have seemed like the opportunity of a lifetime for the band would ultimately end the lives of most of its members. On a flight to a date in Madison, Wisconsin, the plane the artists were traveling in crashed into a lake, killing everyone aboard save for a single passenger: Bar Kays trumpeter Ben Cauley. Redding, who also died in the crash, had reportedly recorded “Sitting on the Dock of the Bay” just a few days prior. As Cauley recounted in a 2007 interview with Memphis Magazine, hearing Redding speak about the song remains one his final memories from the doomed flight.

"That was the first time we heard about 'Dock of the Bay’,” Cauley said. “That's the last thing he talked about — how much he loved that record and that it's something he'd wanted to do for a long time."

The Bar-Kays lost four members: organist Ronnie Caldwell, drummer Carl Cunningham, guitarist Jimmy King, and saxophonist Phalon Jones. The outfit would be later resurrected by Cauley and Bar-Kays bassist James Alexander, who had been lucky enough to be aboard another flight at the time of the accident. In their second incarnation, they achieved both hits and accolades as one of funk’s preeminent acts.

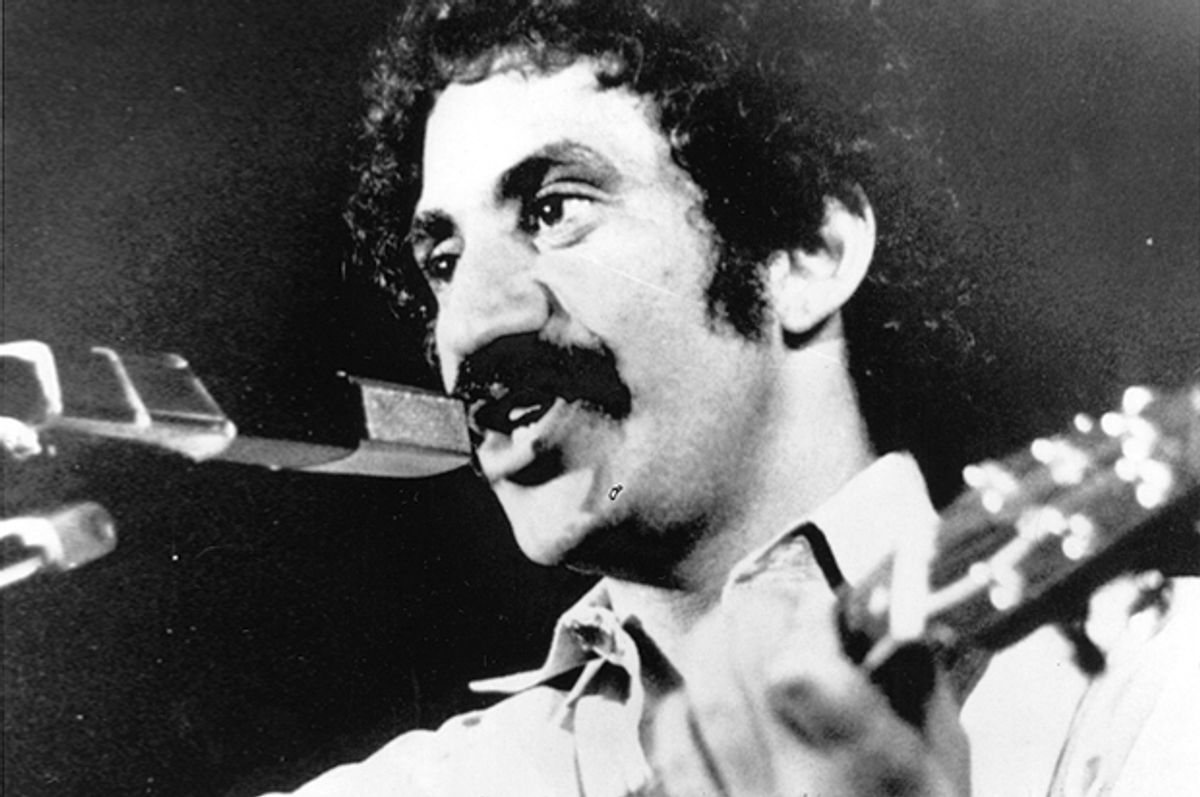

Jim Croce. The man behind “Time in a Bottle” and “Bad, Bad LeRoy Brown” -- a number one hit in the U.S. -- Croce had spent months touring Europe and zigzagging the U.S. with pianist-guitarist and Maury Muehleisen, his musical collaborator, in 1973. In addition, the duo had appeared on well-watched UK and U.S. shows including American Bandstand, the Old Grey Whistle Test and the Tonight Show. And yet, music didn’t seem to be paying the bills; in a familiar tale, nearly everything Croce made on the road was being recouped by his record company for costs they’d fronted. Fatigued and broke, Croce reportedly sent his wife a letter saying he planned to “quit music and stick to writing short stories and movie scripts as a career.”

But Croce never made it home. On September 20, 1973, the chartered flight he and Muehleisen were aboard crashed, the result of what an investigation later revealed was pilot error. Croce’s letter announcing his intention to leave music arrived to his wife after his death.

Reba McIntyre’s Band. Reba McIntyre, “The Queen of Country,” is thankfully still with us. But seven members of the singer’s band, along with her tour manager, were killed in a 1991 plane crash that she happened not to be on board. A chartered flight that had taken off from an airport in San Diego, California, the plane was reportedly scheduled to make two stops: the first to refuel in Amarillo, Texas, and a second at its final destination of Fort Wayne, Indiana. According to McIntyre, when the plane took off, it “hit a rock on the side of Otay Mountain” -- a site roughly 10 miles from its origin airport -- “and it killed everyone on the plane.” (A second flight that left at the same time with McIntyre’s crew made the flight safely.) In the same 2012 interview, a broken up McIntyre said, “I don’t guess it ever quits hurting.” She specially dedicated her 18th album, 1991’s For My Broken Heart, to the members of the band lost on the flight.

Badfinger. Possibly the most heartbreaking story in rock and roll happens to have happened to one of the best bands in its history. Badfinger should’ve been a huge success story, but instead became a cautionary tale for the myriad ways the music industry exploits and throws away so many talented but naive artists. After supporting major outfits including The Yardbirds, Pink Floyd and the Who, the band -- then named the Iveys -- was picked up by manager Bill Collins in 1966. It was a move that would help them reach early stardom and contribute heavily to their downfall. Ray Davies of the Kinks recorded three early demos, which Collins managed to get to Apple Records; Badfinger signed with Apple in 1968, making them the first band that wasn’t the Beatles on the label. After a lineup and name change to Badfinger, Paul McCartney penned their first hit, the timeless power pop classic “Come and Get It.” (Written for the soundtrack of The Magic Christian, a loopy, cameo-filled British comedy starring Ringo Starr and Peter Sellers that’s worth watching for the sheer absurdity of it all.) The song became an international hit. The band’s two primary songwriters, Pete Ham and Tom Evans, also wrote “Without You,” a standard since covered by more than 180 artists, including Shirley Bassey, Andy Williams, Frank Sinatra and, perhaps most famously, Harry Nilsson and Mariah Carey. George Harrison had them play on his 1970 album All Things Must Pass and featured them as part of his backing band at The Concert for Bangladesh in 1971. The point is, Badfinger should’ve been rolling in dough, their names solidified among rock’s most important acts. But taking manager Collins’s advice, the band trusted their money to an American businessman named Stan Polley who absconded with their funds, leaving the band in contractual binds that made it virtually impossible to continue on their own. Lead singer Ham -- by all accounts, an incredibly sensitive, sweet man who believed to the very end in Polley’s honesty despite all indications otherwise -- hanged himself shortly thereafter. (Polley, in a move that even most scumbags would be disgusted by, tried to cash in on Ham’s life insurance.) Inconsolable and unable to restart his own career in music, Tom Evans -- who reportedly said numerous times over the ensuing years that he wanted to be “where [Pete] is” -- also hanged himself eight years later. Badfinger finally got a sliver of the rediscovery they deserve when their 1972 song “Baby Blue” was used in the series finale of Breaking Bad. The nod helped the song’s Spotify streams jump an astounding 9,000 percent in the hours after the show ended, and to sell 5,000 copies of the single on iTunes in a single night.

DeBarge. Motown signed the family of DeBarge siblings -- Bunny, El, James, Mark and Randy -- in 1979. Older brothers Bobby and Tommy, also signed to Motown as part of the band Switch (which has a brilliant catalogue in its own right), helped broker the deal. By the mid-1980s DeBarge had a handful of hits, “crossing over” to achieve both R&B and pop success. In 1985, the single “Rhythm of the Night,” from the film The Last Dragon, became their biggest chart topper, reaching number one on multiple U.S. charts and the top five in the UK. But the family’s early life, marred by violence, poverty and chaos, had imprinted the group with deep trauma that neither money or fame could heal. According to the siblings, their parents’ interracial marriage -- an anomaly in the 1960s -- had made them outcasts wherever they lived. Their father was violent and abusive, regularly beating up both his wife and children. Chico DeBarge (a younger sibling who wasn’t in DeBarge, instead embarking on a solo career) said to Vibe in 2007, “My father sexually molested a lot of my brothers and sisters,” an account substantiated by his siblings. Oldest brother Bobby began using heroin early in his career. By the time DeBarge was reaching their peak success (and had just begun their decline), the siblings had all followed. In 1988, Bobby and Chico were both sentenced to years in jail for drug trafficking. Two years after his release, Bobby died of AIDS-related complications at age 39. Chico found some success after prison with the 1997 album “Long Time No See,” but was again arrested for drug possession 2007. The same year, his brother El would also be arrested for domestic violence, and a year later, for charges related to crack cocaine possession. At last press report, Tommy reported he suffers from severe kidney disease, the result of years of drug abuse. Randy, James and Bunny appeared on a 2011 episode of a show hosted by Dr. Drew to seek help for their drug problems; only Bunny remained in treatment, says she’s still clean, and performs as a gospel singer. James (who was briefly married to Janet Jackson in 1984) is currently serving time for a drug related offense at Los Angeles County's Men's Central Jail. Mark, who was briefly sentenced on drug charges in 2012, now suffers from “chronic debilitation on his legs.” Randy’s current whereabouts were difficult to find, but in a 2011 interview with Jet magazine, his mother claimed he (and Mark) suffers from an “incurable” but non-fatal disease. El, a born-again Christian, says he is now clean, tours with some regularity, and actually sounds pretty great.

Shares