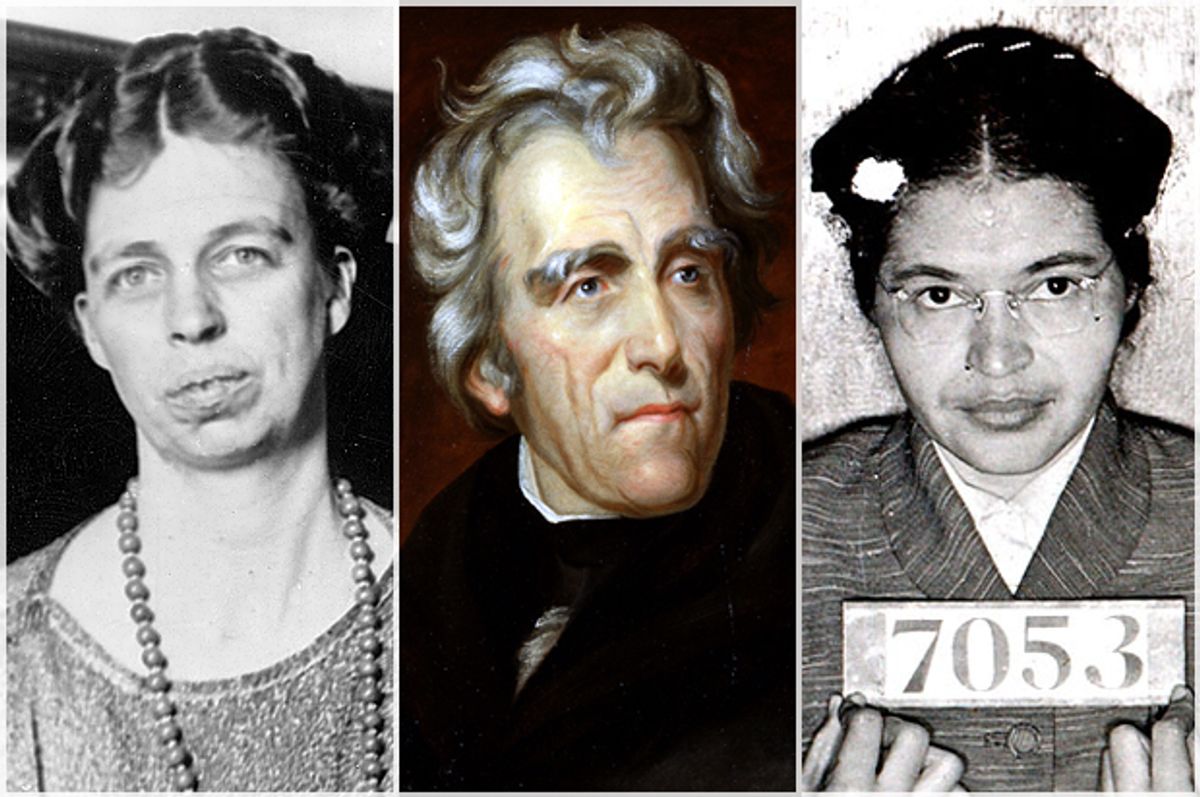

The Treasury Department is poised to honor a woman on the $10 bill. If we project the popular vote, the escaped-slave-turned-abolitionist Harriet Tubman is a likely face for the new ten; First Lady and larger-than-life social liberal Eleanor Roosevelt is also a candidate. But how can a choice be made between the poorest of the poor and a highly visible blueblood?

On the merits, both women are worthy of national honors. Tubman’s personal story is extraordinary: spiritually strong despite being physically and mentally abused, and having witnessed some of the worse cruelties of the nineteenth-century American institution of slavery, this tiny, uneducated woman took fate into her own hands when she repeatedly returned south to rescue scores of slaves. She masterfully eluded fugitive-slave catchers through the decade of the 1850s, and conducted spy missions for the Union during the Civil War.

Eleanor Roosevelt was more than the wife of the one and only four-term president. She was charismatic and committed, ahead of her time as a champion of racial equality and social justice. Not content to be the dutiful domestic lieutenant to a political man, she served as the crippled president’s “legs,” criss-crossing the country and giving rousing speeches. Whether sitting in muddy camps alongside aggrieved World War I veterans and protesting with them the Republican administration’s cruel indifference to the ex-soldiers’ financial plight, or fighting racism by resigning from the snooty Daughters of the American Revolution and staging African-American singer Marian Anderson’s Lincoln Memorial concert, Eleanor Roosevelt took the lead in deepening President Roosevelt’s, and the nation’s, social conscience. After her husband’s death, she pursued an uncompromising human rights agenda in the United Nations.

The other name being bandied about would be the “youngest,” Rosa Parks, the only candidate born in the twentieth century. A civil rights icon, her act of civil disobedience in 1955, disputing an Alabama law that obliged her to surrender her seat on the bus to a white person, made her a living legend. She died in 2005.

Whether it is Harriet or Eleanor or Rosa who graces the ten, the loser in the new equation is the first secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton. Despite his reconfiguration as a hip-hop star in a Broadway musical bearing his name, Hamilton doesn’t belong to our world. The historical Hamilton, a bastard son from the Caribbean island of Nevis who rose to prominence as General Washington’s aide during the Revolutionary War, was an artful social climber who married into one of the wealthiest landed families of New York State. While cunning, egotistical and self-righteous, no one doubted his intellect. He turned his back on the grunts who gave up their agricultural livelihood to fight for the country’s independence, embracing instead the interests of a moneyed elite whose patience and support for a financially strapped federal government was required to prop up a deeply indebted regime. That was the choice he made.

Oddly, then, Hamilton, the darling of modern fiscal conservatives for taking risks and marshaling the power of private capital, was a proponent of a bigger, more intrusive, and consolidated government; Hamilton’s political opponents wanted government to be more inclusive, to better represent the voiceless. For those capable of appreciating irony, featuring Hamilton’s image on currency has served as a reminder that the American republic has never really privileged democratic impulses—that’s what changes when a Harriet Tubman or an Eleanor Roosevelt gets the nod.

Perhaps the greater irony is the persistence of Andrew Jackson on the twenty. The stormy-haired image on the modern bill gives the gaunt, bloodsoaked warrior a rather more Hollywood look. Long hailed as the prototypical democrat, “the man of the people,” the historical Jackson may have courted such a desirable image, but it is less than wholly true. First of all, it was his loyal subalterns, select officers who served with him in Alabama, Louisiana and Florida, who crafted Jackson’s storied image as a natural-born hero and carried out a highly effective publicity campaign that eventually won him the White House. Yet these same opinion makers came to regard “The Hero” as a danger to the republic. Lawyer-politicians like campaign biographer/Secretary of War John Henry Eaton and fellow Tennessee politician Hugh Lawson White, a longtime ally, banker, U.S. senator and champion of Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, grew tired of the brash, ill-educated, unteachable egotist, and defected to the Whig Party, a political party more or less invented for the sole purpose of contesting the Jackson image.

The man who dictated terms to Indians — including those allied with him, who fought for him, only to be shorn of their ancestral lands -- and believed he should dictate terms to everyone else. The so-called democrat who famously hated banks and bankers actually represented people like himself: white men on the make; who bought and sold land, traded in slaves, and gambled on the future. Jackson did not even believe that men without property should be granted the vote in his home state. His democratic pose (and less than democratic reality) is not as remote from Hamiltonian elitism as some people would like to believe.

Perhaps the best way to resolve the Tubman-Roosevelt contest is not to make this into a fight over an upper-versus lower-class heroine; but rather to give one of these peace- and integrity-promoting figures the ten-dollar bill and give the other the twenty. The time for tokenism is past. The selection of Sacagawea for the one-dollar coin in the year 2000 served no purpose other than tokenism. What was she being celebrated for? Leading some white guys through the Plains states while carrying a papoose on her back? Next in line for a coin might be Lucretia Mott, a real nineteenth-century feminist, a Quaker minister precious few Americans have heard of, but who is arguably the most progressive voice among generations of moral reformers. She stood, early on, for abolition, women’s rights and homesteads for landless citizens, and she vocally opposed wars of conquest. Sacagawea had strength of will, but Mott was a true pioneer.

Sandra Day O’Connor was not the first woman appointed to the Supreme Court so as to be its token woman—more than one woman can sit on the High Court, and more than one woman can appear on our greenbacks.

Shares