In her new memoir, Sarah Hepola sometimes sounds as if she’s lived the dream of hundreds of thousands of readers of those books with pink cocktail glasses and high heels on their covers. She was a rock critic, a freelance writer in Manhattan, sent to Paris on assignments and surrounded by smart, loving friends. She’s even been an editor at this very publication, where she has assigned and published personal essays of wit and power, helping other writers tell stories many of us have found unforgettable, as well as writing quite a few them herself. At work she was a force of nature the way sunshine is, able to bring warmth, intelligence and a sparkling energy to even the most lackadaisical afternoon meeting.

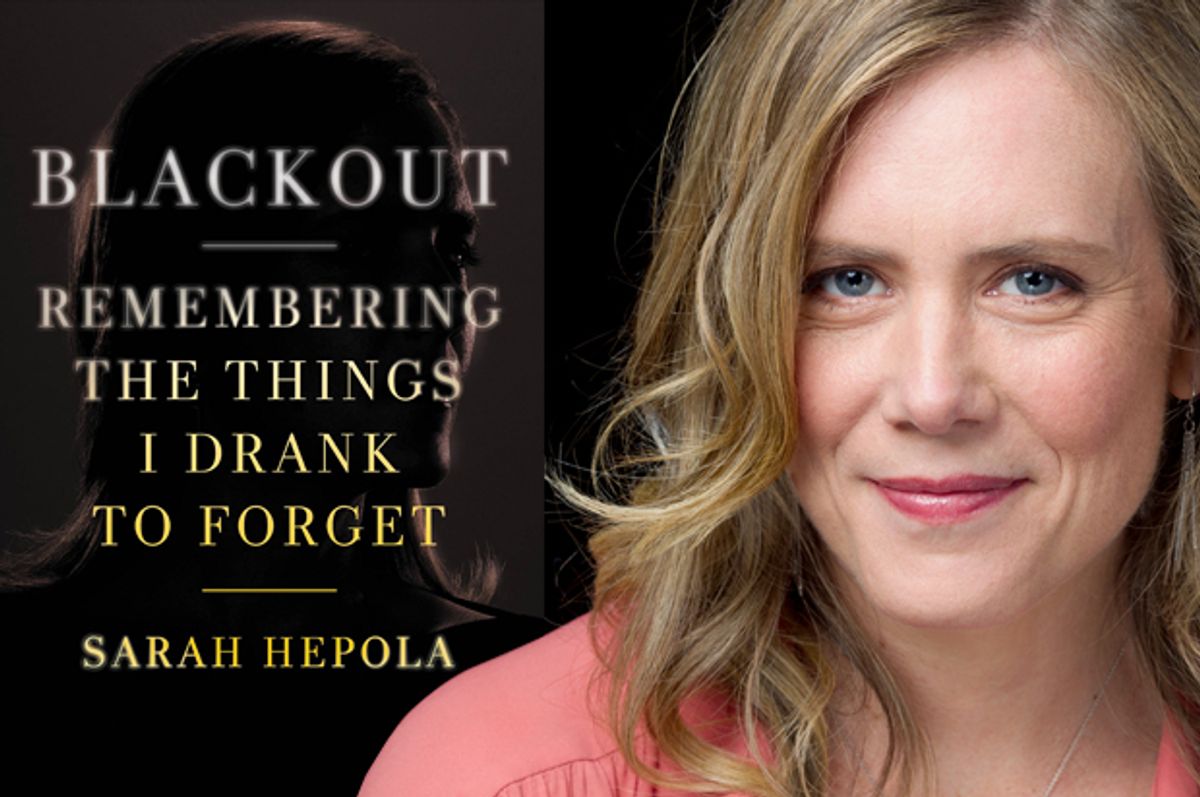

Sarah’s closest friends, however, understood that she was also an alcoholic, prone to episodes of total memory loss during which she said and did things that often seemed wildly out of character. “Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget” opens with its author in Paris, but also coming to in bed with a man she doesn’t even remember meeting in a room she doesn’t recognize. It wasn’t the first or the last time Sarah had that experience, the sort of thing that she and her friends once embraced as fearless, feminist escapades. Less glamorous was waking up after a party curled up in a dog bed.

“Blackout” describes Sarah’s efforts to find out how she came to lose so much time, and the long and difficult road to a life she could call her own. It’s sad and funny and sometimes scary, but always infused with a radiance you want to bask in. I recently reached her by phone in Dallas, where she now lives, to find out more.

I’m not much of a drinker, so a lot of “Blackout” was news to me. I should have known that there was a difference between passing out and having a blackout.

It’s amazing to me how common that misperception is, even among my most educated friends. These are incredibly smart, well-read, sophisticated people, and for years they have read the term “blacking out” and thought that it meant passing out. I get why, because it sounds like your brain wound down — but it’s very different. You’re still going.

There’s some version of yourself, like a person who you don’t even know, who’s in charge of the ranch and running around, doing stuff. Presumably it’s some part of you, even though she’s doing things that you would never do if you were sober. How long can these periods last?

There’s two kind of blackouts: fragmentary and en bloc. The fragmentary can last a few minutes, five minutes, 30 minutes. The en bloc type, they can last hours. The blackout that I write about from my college years, the one where I was with friends in a car and was mooning everybody? I believe that one was at least three or four hours.

During which time you were conscious?

I was conscious. Just to be clear: When you’re in a blackout, you can still make decisions, and you’re basically interacting like a drunk person would. I presented as a drunk person, and I was making the decisions that a very drunk person would make. But the recorder in my brain wasn’t going. So later, I have no memory of all this, even though I was conscious at the time, which, to me, challenges the question of what is consciousness. But, if you look at legal cases — and this is a lot of stuff that I didn’t get into in the book, because it has a lot of rabbit holes — they’ve determine that people in a blackout are responsible for their behavior.

But I get the impression that your behavior during a blackout was very different from even your usual behavior when you were drunk but capable of remembering.

It was. When I first found out that I had mooned everybody from that car, that was the craziest the thing! I mean, I start that chapter talking about how self-conscious I am about my ass. I used to wear a shirt tied around my waist to cover that up! So, what am I doing?! I did sometimes feel like, “Oh, this is an evil twin.” But I also think that I was a young person who didn’t quite understand what alcohol does to her. In a way, that person [during the blackouts] is very much me — me without my governors, me without any inhibitions whatsoever. I don’t know what to say about it, because some of this stuff is mysterious. There hasn’t been that much research about blackouts.

I come from a family of sleepwalkers, and it’s similar; you don’t remember what you did, but you appear to be conscious to other people.

I just made the sleepwalking comparison yesterday, on NPR’s “Weekend Edition.” I think it has parallels, but when somebody’s sleepwalking, can’t you see that they’re sleepwalking?

Well, it’s easy to see that they’re not their normal selves, and if it’s nighttime and you know they sleepwalk, you put it together. For example, when I was a child, my sister came into bedroom and sat on the floor and started to ask me a lot of questions that were intelligible but made no sense. But her eyes were open, she was walking around, and of course she had no memory of this afterwards. I knew she was sleepwalking because it was night and she was in her pajamas and there was a lot of that sort of thing going on in our house. But if she had been walking down the street and said those things to me, I might just have thought she was a crazy person. People have driven cars and done all kinds of stuff while sleepwalking, and I don’t know that anybody who saw them without those cues would know what they were doing.

Aaron White, the researcher I interviewed at NIAAA [National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism], said to me that blackouts look like early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Right, because you have just a few minutes of short-term memory and no long-term memory?

Exactly, and that looks exactly like when somebody’s hippocampus is snipped out — the guy in “Memento” had that.

So you can remember the last two or three minutes of what’s happened, but then after that you keep forgetting, so you keep repeating the same things over and over again?

And that’s the drunkard’s loop, as a friend calls it!

How often would this happen to you? A rare occurrence, or weekly or monthly?

At the beginning, especially, it was a rare occurrence. Sometimes people read the book and they think I blacked out every time I drank. I don’t know that I would have kept drinking as long as I did [had that been the case]. There would be years between those episodes. But as I got into college, and as I got into my 20s, it was becoming more common. It wasn’t always dramatic — like that three-hour blackout that I told you about. I wasn’t having those. But I was having 30 minutes or an hour, especially at the end of a night, that I just wouldn’t remember. Sometimes it was no big deal, and then sometimes there’d be hell to pay, because I had said something. I think I had probably 10 of those really awful en bloc blackouts, and then probably about 50 of the fragmentary blackouts. But that’s a total guess, because we’re talking about years and years of drinking.

One of things that you convey so well in this book is how much you enjoyed alcohol from an incredibly early age — especially beer. You also look at a bunch of elements from your childhood, and ask, “OK, did this set me up for this, did this experience predispose me in some way to be dependent on alcohol?” But clearly, as you say at the end, there’s such a genetic component. Even as child of 6, your little sips of beer were just ecstatic. When I read about that, I had to wonder if writing this book was dangerous for you.

There’s something in recovery called “euphoric recall,” which they warn you against. It’s dangerous.

Dangerous just to remember how great it felt to drink?

Yeah! That’s like obsessing about an old flame — what good could come of this? I acknowledge that it was a little dangerous, but it also felt very necessary for the book, and I wanted it to be true. Those first sips of beer, for whatever crazy reason, I loved the taste of. When I later learned that every other kid hated the taste of beer — that to me is the biggest clue.

That amazed me. I hated it so much as a child.

And that’s the universal experience! That tells you right there. There’s something different about me. But I didn’t know that I was different. Back when I was stealing sips of beers, my parents told me not to do a lot of things, and I did them anyway. My parents told me not to watch television! There was some part of me that liked the thrill of it and was trying to figure out how much I could get away with. But, believe me, I wouldn’t have been doing it if I didn’t love it. I loved how it made me light-headed, too. I would spin around the living room, and I would fall over. And that makes me kind of sad, because that’s what kids do anyway. Why did I need a substance to do that? Genetics is just so strong — I’m Irish and Finnish, and they’re very strong drinking cultures.

I was also struck by the scene where, after you’d gotten sober, you passed a homeless drunk on the street, and you say, “I just inhaled —”

And my mouth watered!

Like a vampire!

I felt like such a fallen person that day. I still remember it — I passed somebody on the subway, and they smelled like beer, and I just felt sunk.

Do you feel that still? Like if you walk past a bar?

My mouth doesn’t water … but yeah, that smell is always going to cause a “Woop! Woop!” Anybody in recovery is well-advised not to hang the “Mission Accomplished” sign. I have to be very vigilant about these things, but the thing is I don’t crave alcohol like I used to. I can be in a bar and it doesn’t worry me, but at the same time I also don’t spend much time in them.

There was a real link in your life between writing and drinking. And there’s also this great part toward the end where you talk about dating while sober and how you can’t imagine getting to the point of kissing someone without having a drink. That’s kind of the same thing. There’s a particular way of putting yourself out there that’s common to both writing and kissing. Can you talk about how drinking affected your writing, and what it was like to stop?

I think that’s true, that putting yourself out there is the common theme.

With writing, when I was a kid, I wrote freely and easily. I loved it and I went to it because it felt good. And I was good at it. But by the time I got into my 20s, my head was full of criticism and doubt. The first paper that I worked at, the Austin Chronicle, I wanted so hard to impress my colleagues and be as good as them, and as good as my heroes. I had a very hard time sitting down to write. I would literally sit at my desk for an entire day staring at a blank screen.

The tenacity of that is kind of impressive to me. I would write a sentence and erase it, write a sentence and erase it. I would go outside and I would smoke, because I was smoking back then. And I would think about what I was going to write. What you’re seeing right there is a profound lack of self-confidence. I had lost my nerve and I had lost my voice. Whatever I wrote, that internal critic was like, “Not good enough.” So I did the thing that I had learned to do in other settings — to lower my inhibitions and allow myself to take that trust fall — which was drinking. At first, it was just a few drinks. Then it became more. I experimented with just getting really drunk and writing. I know musicians who do this. The thing is, I would wake up and I would think, “That’s not bad!”

I love that you admit that. You had inhibitions, and alcohol really liberated you. Do you ever wonder if maybe the girl mooning in the car or the girl writing the kick-ass music review was the real you?

What we’re going to discover is that I just have this deep-seated desire to moon people! As I moved into personal writing in particular, in my late 20s, I stopped needing that alcohol. This was my story, and nobody could tell me otherwise. I didn’t feel I had the authority of a critic or a straight-ahead journalist. I always felt insufficient. When I started doing personal writing, nobody could tell me I was wrong about it — which isn’t true, because they still do.

Do they ever! Writing about yourself on the Internet seems to give every creep the license to tell you how wrong you are about your own life!

[Laughs.] But I stopped needing it so much. The need to drink to write came back around my years in New York. Or maybe the opposite was true then — that I needed an excuse to drink. It was like: I’m home alone, I’ve got to work on a story, and, oh, the drinking will help. At that point, I was using it as an excuse to drink all the time. I used to leave work at about 5 or 6 and I would go to one of the steakhouses in the area, and sit at the bar, order some wine and work on my laptop. If you’re working on a laptop, nobody can tell you you’re some lame woman at the bar drinking alone. I’m working, you guys! On Salon’s Sexiest Man issue!

When I stopped drinking, I just felt so fragile, and I did not think I would write again. I was having these bad panic attacks, and I had a couple of relapses — I don’t get into this too much in the book, because you can’t stay forever in relapse land. But I had a couple of relapses trying to do a story, because the old thing came back where I’d sit in front of the screen and I couldn’t write and hours went by. I would obsess, and think, “I have to get this story, I have to get a six pack of beer.” In fact, I relapsed writing a story about cats on the Internet, which really is a low point that should have been in the book!

I admire the way you admit how unpleasant it was for you to go sober, how you expected to feel liberated, and then how awful you felt.

People kept telling me, “It’s just going to be so great! You’re going to be on a pink cloud!” And I had read a couple of books where it seemed like people just quit. And I was so unhappy. I didn’t want to quit, I really, really didn’t — I felt like I was losing my social circle, and the happiness I had known. I was deeply unhappy for that year, and probably into the second year. The second year was when it started getting better, but that first year, and especially those first six months …

How do you stick with something when you really don’t want to do it and it’s not making you feel better?

That was the hardest thing, obviously that’s why I stayed in relapse for so long. I would just keep saying I would quit and I didn’t. One of the lies I told myself when I was drinking was that I didn’t hurt anybody else, and that it was only about me — just me in my apartment. But I was starting to see that I had actually hurt the people close to me, because they had worried about me so much. In particular, my mom.

My mother and father are very supportive parents. They’re still the parents that any hand-drawn stick figure you give them is just, “Amazing! How’d you do this!” And I had protected them from knowing the depth of what I was going through. A lot of people had looked at me and thought, “She’ll get it together. We know she’s going through a tough time, but she’ll get herself together.” And that is what my parents thought. But when I got real with my mother, and told her what was happening in my life, and she could sense the stakes of what was going on — I couldn’t do that to her.

Couldn’t let yourself relapse, again, you mean?

Yeah, I mean, I had created so much worry for them! There had been a few times when I had told them, “Hey! I’ve quit!” and then two weeks later I was back again. My parents are just two of the many people in my life for whom this was an issue. When I started telling people about what a problem I had — and a lot of people saw some of it, most of the people close to me saw some of it — when I’d share those things with them … Once you start making yourself accountable to people, it’s really hard to walk it back.

Six months in, one of the reasons I wrote a story about it for Salon — which again, I’m not sure I’d recommend for other people, but I did do that — was I needed to be on record. I needed to do everything I could to not let those people down again.

I got very connected with the personal essay writers who were doing stories for me at that time. It seemed to me that they were doing a brave thing, which was to walk out onto the Internet, at that time in history. There were so few barriers between them and the world that wanted to tell them that they had nothing to say of value. And these people were still doing it! A lot of times I would stay up late emailing with them. I got very close to those people writing for me at that time. I felt the responsibility to be present in my life and the people in it, because I had checked out for some time. Those were the things that spurred me on. But yes, it’s incredibly hard to quit something when you are not rewarded for it.

You mentioned that your fear of quitting was partly that your social life was wrapped up in drinking. But it also seems that you’d alienated a lot of your friends.

That was one of the painful discoveries of those first six months, as well. One of the lies that I continued to tell myself was that drinking made me a better person and a better friend. The further I got away from the drink, the more that revealed itself to be a delusion. I had a friend recently tell me, “I was so worried about you, I’d been worried for years,” and I did not know that friend was worried about me. Friends are weird. A lot of times we don’t know how to be supportive. What is support for a person in need? Is it not saying anything? Or is it saying something? I don’t think there’s an answer to that.

You’re in AA now?

Yes.

You had a rocky relationship with AA, which has come into some criticism. And you’ve never gone to rehab. How has your view of it changed?

I had a real allergy to AA, for I think the typical reasons: I was freaked out by the God stuff. I thought it was kind of cult-like. I’m very grateful that I saw people who I looked up to embrace it. One of them was Caroline Knapp, in her book “Drinking: A Love Story.” I also remember David Foster Wallace talking to you in an interview about AA, and what he said really stuck with me. And there were other people in my life who were writers, who said, “This is what really worked for me.” They would point me away from the stuff I really wanted to go to, and point me toward the stuff that fed your soul, and was quietly profound, that had saved them and would save me too.

I think it’s an extraordinary program, and the reason that I included it in my book was that I wanted to speak to people like me who had that resistance, that allergy to it. I know right now there’s a conversation around how we treat addiction, and I think we should be having those conversations. But there is a conflation of the rehab industry, which is a money-making industry, and AA, which is a giant anarchy. AA asks for $1 or $2 donations, and nothing more, and is available all over if you want it. The rehab industry is separate. For a lot of people AA is what works. It worked for me. And I’m so grateful — even though I know the issues around anonymity — to the people who opened the door for me to think about it in a different way. The writers. To be clear, David Foster Wallace never admitted that he’d done it, to my knowledge, but he spoke so eloquently about AA, and “Infinite Jest” is such a brilliant book about addiction and recovery. Those are things that opened the door for me.

I remember him saying it’s especially tricky for writers, who value freshness in language, to handle the slogans and clichés.

There was so much of my ego and exceptionalism tied up in that. I’ve been trying to let go of it, to know that this does apply to me, too. I’m just a person. I am.

Shares