“I’m not going to be your boyfriend,” Justin told me as he lay in my bed and fired up a cigarette.

“I know,” I lied, and told him to put out the cigarette. My mom didn’t let me smoke in the house, and I mostly tried to obey her. Justin made fun of me. He called me a baby, said I wasn’t a real smoker because all real smokers smoke in bed. I found his logic more convincing than my desire to remain my mother’s good girl. Together, he and I puffed away.

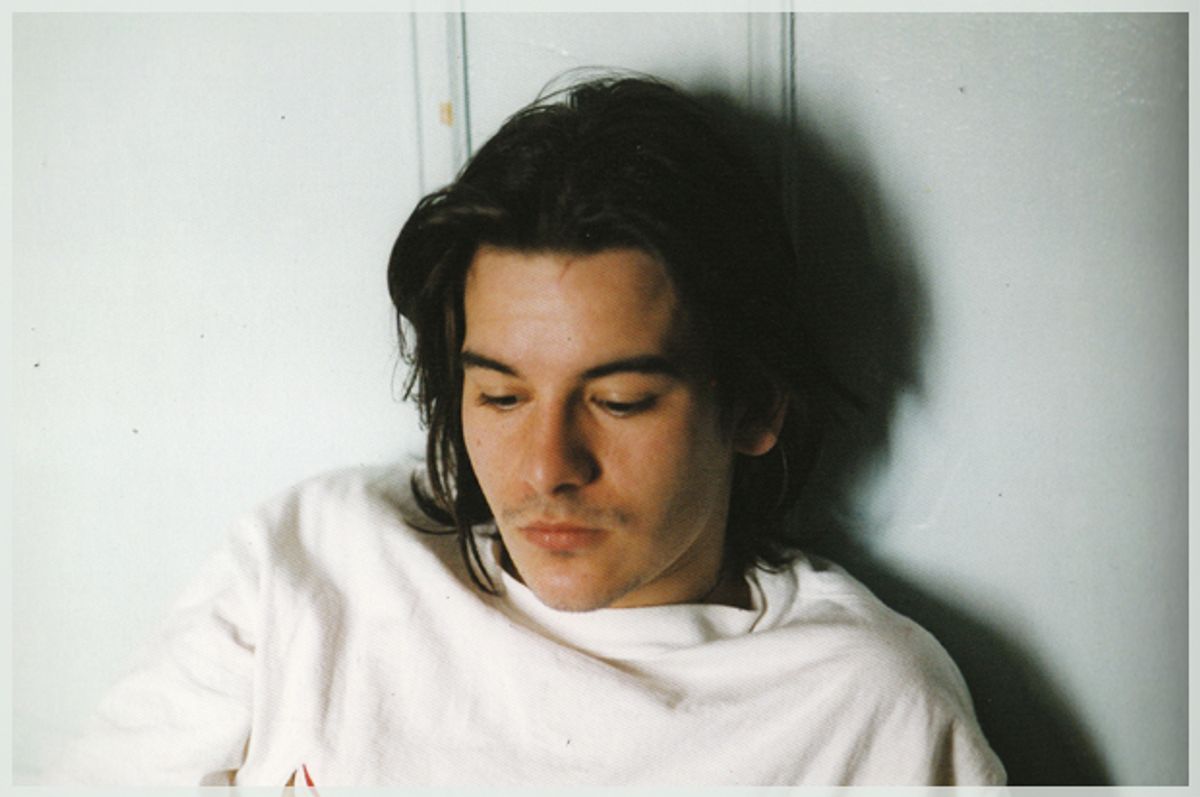

He asked if I was a virgin before I came to him and I told him, “No.” Another lie. He didn’t believe me for a second and I felt like a fool. Then he told me that he was a bastard; literally, he had no father and this was hard on him growing up. I didn’t know what to do with this and the other terrible things he told me. Even now, 20 years later, I still don’t know, because after all, what does one do with the secrets of the dead? I remember him hooded in a Zoo York sweat shirt, smoke rising from my pillow, his mouth a laceration. I don’t know why he confided in me. I wasn’t special; I was just there.

It was the summer of 1995. Justin had shot a movie called "Kids," which was about to be released. The way he talked about it, you could tell he was proud, but he also didn’t think it was that big of a deal. He got paid something like a thousand dollars to play Casper, the raunchy sidekick of an HIV-positive protagonist who skates around New York City on a mission to fuck virgins. The critical and commercial success of Larry Clark’s Direct Cinema cult-classic "Kids," which reportedly grossed over $20 million, came as complete shock to the cast, mostly composed of non-actors—but rather skaters like Justin—and sexy street urchins who went on to have illustrious film careers. Clark’s portrayal of the kids, through unflinching close-ups and hyper-sexualized scenes, were designed to alarm the viewer, and without a voice-over or outside narration, the film banked on being a keyhole into what teens were doing when no one was looking. You see, this was before Facebook. Before Instagram. Before Snapchat.

Though the success of the film would score Justin a Hollywood agent, to me, he remains the lost boy who took my naiveté, trampled it with sex and death and handed it back.

At 17 I was a far cry from a tomboy, but ever since meeting the skaters, I started riding my bike around the city. I moved fluidly, sometimes drunkenly, from Carroll Gardens to Chinatown, inflicting just enough scrapes and bruises on my body to make me want to ride faster, better, straddling the seat of my 10-speed Ross. I got a new perspective on the city. I got a new perspective on myself. This was one I desperately, in the most guttural way, needed. In the fall I’d move uptown to Barnard College and study writing and sociology, but in the meantime my family was falling apart.

I was a slutty virgin who’d exhausted a host of artsy private-school white-girl problems, from shoplifting to anorexia, but I couldn’t find a release for my pain. Sometimes, it loomed just beneath the surface—a clogged pore, a forgettable failure. Other times it was debilitating—a razor too close to the vein, a trip back home to make sure the gas was turned off, the dog still alive. This pain made me retreat into myself and need to be seen at the same time. It was pain from finding club fliers in my dad’s underwear drawer with men’s names and phone numbers scrawled on the backs, pain from a mediocre grade on my trig test. I seemed to be fooling everyone and no one that I had it together. I’d only done coke a handful of times, but let on that I had a problem. My pain was real even if my problems were fabrications, or had no name. I was a kid going on 80.

This was my teenage wasteland. It was filled with lost boys who’d help me find a version of myself I could wear out in the world. I’d get tattoos, crash my bike, let guys give me hickies, and think to myself I could be like the skaters. I too could scar my body like the scabs they collected on their elbows, knees and hips, these scars that made them warriors.

Summer was their time to rule the streets, and by now I was acquainted with their haunts—Tompkins, Astor, the Banks. At 7 o’clock they’d meet at Supreme when the gate went down, the manager counting the day's sales and someone rolling a blunt in the back. Beers were cracked and wheels hit the pavement on Lafayette, passersby stopping for a moment to take in the motley crew thrashing over an obstacle course of trashcans.

This was before skateboarding was cool.

What was I doing there? Everything and nothing. That summer was thick, the temperature building to a fever right before it breaks. Before planes crashed into buildings and the shops on the Lower East Side were interchangeable with those on Madison Avenue. Before Columbine christened a new era of adolescent assassins, before reality television became a cultural mainstay, before MTV’s teen moms filled the glossies with their latest sex tapes. The release of "Kids" 20 years ago was in so many ways a beautiful, prophetic disaster, a last call for a New York that has since been replaced with vestiges, facades and memorials.

My best friend and I had been chasing the skaters all winter, which is how I found myself in bed with Justin, a couple of days after my high school graduation. Sneaking him into my brownstone was the easy part; once he was in, things got hard. Back then, I was too young to know the distinction between sex and love, and, also, it was the first time I felt that kind of deep emotion. Before I had a chance to unload my feelings, he said, “I’m in love with my ex-girlfriend.” Then he kissed me on the mouth. He kissed my clavicle, the only long bone in the body that lies horizontally. He spread my legs and kissed inside me. He didn’t love me, but he made me come.

After, he asked me if I ever thought of how I’d kill myself.

“Have you?”

“Yeah, of course,” he said.

I didn’t know what to say. I wouldn’t know how to answer that question until my early 30s, when my first book tanked and my live-in boyfriend took off in the middle of the night five weeks after I lost the baby we were planning on bringing into this world. My depression got so bad, suicidal ideation would lull me to sleep (jumping off a roof; drowning in a bathtub). Justin hanged himself in the Bellagio Hotel. I often think about what he fashioned for a noose.

But all of this would be many years later. I had fallen hard for my first, but it was more than that. I didn’t have to be that special to him. We were both hooked on the momentum of melancholy, and wrestled with how to show our pain to the world. Like any other addict, he had these antennae that detected in me the frequency of a kindred spirit. Of course, as a teenage girl, I didn’t have the self-awareness to put any of this into cogent thoughts, but I let him inside me knowing by doing so I was setting myself up for heartache. He told me from the get, he wasn’t going to be my boyfriend.

That didn’t deter my romantic efforts. Nothing really could. Even when I called his house and he hung up on me. Even when I showed up at skate spots with beer and he took the beer and left me on the curb. Nothing fazed me. I’d just lie my way into parties filled with important people. I was still a transparent liar, but it seemed people didn’t always care that you lied. I was learning.

Then he broke his leg, which made him easier to find. I was relentless in what could only be called my stalking of him, because it was just so good when he forgot he didn’t like me. It was just so good when he held me tight to his body so his smell, which possessed unearthly power, could coat me and take me into oblivion.

“I thought you were buggin', girl,” he told me, “but you are straight up crazy.” A smile curled from his upper lip, and I felt what everyone who has ever been on the outside looking in feels when she is understood: less alone.

Still, I was a baby. I was a baby regardless of the furrowing precocious pain that I’d been taught was supposed to signal some sort of growth. On the nights when I got his roommate at his house in Sunset Park to let me in, I knew to creep into his bed and lie in wait. When he staggered home to find me, he responded by quoting Biggie lyrics. We got high and laughed at my absurdness, his crazy life, and I knew this was what fun felt like. Afterward, the house was silent. I couldn’t sleep. I didn’t know what to do with my feelings. Was this real? In the kitchen, I smoked one of his Newports and sat at the table and stared at a drawing of a totem pole that bore his last name. A friend, a skater and artist who also lived at the Brooklyn house, had taken hours with faint pencil strokes to make it for him. It was matted and framed and hung level with my eye line. Back in the day, totems represented your clan; totems were how you left your mark. A cockroach came out of nowhere and shuttled across the drawing. I was too frightened to crawl back in bed and wake up with him. So I left his house just before dawn and found a car service called Monchito’s to take me home.

It was easier to leave—that’s what they all say, right? That’s because it’s true. There are some things you can’t know until after. Like this is the last time I will see this person alive. Or the whole time you thought you were on the outside looking in, you were a part of something that can never be re-created. And how leaving doesn’t make things easier; it just creates space.

I don’t know for sure why people are so obsessed with films about coming-of-age, but I have a theory. As kids mature into adults, we’re supposed to come to terms with our unshakable aloneness. But what happens if we can’t? There’s melancholy that drives success and melancholy that drives something darker. The legacy of this iconic movie that starred this boy I loved doesn’t differentiate between the two kinds of melancholy. The critics said the close-up shots of kids were exploitative but they made the audience feel let in on a secret: Here’s a peep into the invincible naiveté of adolescence some spend the rest of our lives trying to relive. Twenty years later, I wish I could shake my teenage self, and tell her to let go of the pain and just ride. It won’t ever feel like this again, girl.

Shares